BUDET Report Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural and Scientific Collaboration Between Czechoslovakia and Cuba in the 1960S, 70S and 80Se Words and Silences, Vol 6, No 2 December 2012 Pp

Hana Bortlova “It Was a Call from the Revolution” – Cultural and Scientific Collaboration between Czechoslovakia and Cuba in the 1960s, 70s and 80se Words and Silences, Vol 6, No 2 December 2012 Pp. 12-17 cc International Oral History Association Words and Silences is the official on-line journal of the International Oral History Association. It is an internationally peer reviewed, high quality forum for oral historians from a wide range of disciplines and a means for the professional community to share projects and current trends of oral history from around the world. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. wordsandsilences.org ISSN 1405-6410 Online ISSN 2222-4181 “IT WAS A CALL FROM THE REVOLUTION” – CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC COLLABORATION BETWEEN CZECHOSLOVAKIA AND CUBA IN THE 1960S, 70S AND 80S Hana Bortlova Oral History Center Institute for Contemporary History Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic [email protected] Although traditional relationships between Cuba Culture was established in Prague. In the scientific field, the Czechoslovak Academy of and Czechoslovakia, economic above all, go back Sciences contributed significantly to the creation further than the second half of the twentieth of the Academy of Sciences of Cuba; starting in century, the political and social changes in Cuba at 1963 there was an agreement to directly the end of the fifties and the beginning of the collaborate between the two organizations. The sixties and the rise of Fidel Castro to power and his institutes intensely collaborated above all on inclination to Marxism-Leninism were what biological science, but there was also important marked the start of the close contact between the collaboration in the fields of geography, geology, two countries that would last three decades. -

Die Welt Der Slaven

D I E W E L T D E R S L AV E N S A M M E L B Ä N D E · С Б О Р Н И К И Herausgegeben von Peter Rehder (München) und Igor Smirnov (Konstanz) Band 54 2014 Verlag Otto Sagner München – Berlin – Washington/D.C. Sammelband_Slawistik.indd 2 07.11.14 13:29 Fashion, Consumption and Everyday Culture in the Soviet Union between 1945 and 1985 Edited by Eva Hausbacher Elena Huber Julia Hargaßner 2014 Verlag Otto Sagner München – Berlin – Washington/D.C. Sammelband_Slawistik.indd 3 07.11.14 13:29 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort ............................................................................................................................... 7 Sozialistische Mode Djurdja Bartlett ................................................................................................................ 9 Myth and Reality: Five-Year Plans and Socialist Fashion Ulrike Goldschweer ......................................................................................................... 31 Consumption / Culture / Communism: The Significance of Terminology or Some Realities and Myths of Socialist Consumption Катарина Клингсайс .................................................................................................... 49 Этот многоликий мир моды. Образец позднесоветского дискурса моды Mode und Gesellschaft Анна Иванова ................................................................................................................. 73 «Самопал по фирму»: Подпольное производство одежды в СССР в 1960–1980-е годы Irina Mukhina ................................................................................................................ -

Povl Tiedemann's Meritter Og Historik

Povl Tiedemann’s meritter og historik 1 Til Anne fra Far På opfordring af Mor 2 Dahls Foto, Holstebro, 1955 3 Indholdsoversigt Side 1948 – 1955 Stenhøj 6 1955 – 1962 Grundskole 7 1962 – 1965 Realskole 9 1965 – 1968 Shippingelev 11 1968 – 1968 Shipping Volontør 16 1968 – 1970 Handelsgymnasium 21 1970 – 1975 Handelshøjskole 25 1976 – 1976 Erhv. Eksportfremme Sekr. 33 1976 – 1977 MÆRSK 34 1977 – 1981 Handelskammeret 40 1981 – 1987 LEGO 53 -Power-Play i Østeuropa -Statshandel -Modkøb og valutaforhold -Modkøbsvarer og distribution -Interessante eksempler -Østeuropæiske kontakter -Anvendelse af LEGO vareprøver -Rejse- og repræsentationsforhold -Leipzig Messen – business basis -Poznan Messen 1981 – optakt til slutspil -Nye muligheder i USSR -USSR stop og genstart i Moskva -Åbning til Kina -Diverse omkring Kina -Modkøb intensiveres og problematiseres -Finale LEGO -Et par centrale navne -Hændelser og iagttagelser under vejs 106 -Nationale forskelligheder -Kontakt / forhandling / samarbejde -Overvågning -Produktudvikling / innovation / kreativitet -Overordnede betragtninger -Efterskrift - ”Fugl Føniks” 134 1987 – 1991 Handelskammeret 136 4 -Sidste tur gennem ingenmandsland 1992 – 1996 Div. + underv. + censorakt. 143 1996 – 2009 Civiløkonomerne 147 -Hændelser under vejs 2009 – 2013 Censorsekretariaterne / censorerne.dk 170 -Diverse ”Red Tape” -Hændelser under vejs 2013 – 2018 Censor IT / 178 Censorformandskaberne -Sporskifte til formandskaberne 2014 – XXXX Ældrerådet i Vejle Kommune 182 Lidt om min Eva 183 SummaSummarum – Eftertænksomheder 185 Lidt fra ”tidsmaskinen” 191 Personal Card – CV i TACIS opstilling 195 Hovedaktiviteter for Civiløkonomerne 205 Billeder og -forklaringer 209 Kalligrafi og protokol 241 ”Kineserier” fra LEGO-personalebladet Klodshans 245 Bibliografi 256 Links 259 5 1948 – 1955: Stenhøj Opvokset som den yngste – årgang 1948 – blandt 3 søskende, på en landejendom på ”Stenhøj”, Foldingbrovej 15, Rødekro, 13 km. -

Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin

Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin Boston University During the 1970s, a joke circulated in the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, that deftly paraphrases the peculiar problem of money in Soviet-style regimes. Two men, eager to enrich themselves by producing counterfeit bank notes, mistakenly print 70-mark bills. To improve their chances of unloading the fake notes without getting caught, they decide to travel to the provinces. Sure enough, they find a sleepy state-run retail outlet in a remote East German village. The first forger turns to his colleague and says, “Maybe you should try to buy a pack of cigarettes with the 70-mark bill first.” The second counterfeiter agrees, and disappears into the store. When he returns a few minutes later, the first man asks him how it went. “Great,” says the second man, “they didn’t notice anything at all. Here are the cigarettes, and here’s our change: two 30-mark bills and two 4-mark bills.”1 Like much of the black humor inspired by authoritarian rule, the joke makes use of irony to render unlike things commensurate. This particular joke acquires a subversive edge from its equation of communism with forgery. The two men successfully dupe the state-run store into accepting their phony bills, but the socialist state replies in kind by passing on equally fake money. The joke does not exhaust itself, however, in an attack on the moral integrity of communism, which responds to one crime with another, or even with the powerful suggestion that any regime that counterfeits its own currency must be a sham. -

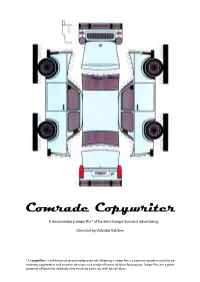

Comrade Copywriter

Comrade Copywriter A documentary swipe file* of Eastern Europe Socialist advertising. Directed by Valentin Valchev. *A swipe file is a collection of tested and proven ads. Keeping a swipe file is a common practice used by ad- vertising copywriters and creative directors as a ready reference of ideas for projects. Swipe files are a great jumping-off point for anybody who needs to come up with lots of ideas. 1 Synopsis “What is the difference between Capitalism and Socialism? Capitalism is the exploitation of humans by humans. Socialism is the opposite.” an East German joke from the times of the DDR For more than half a century a vast part of the world inhabited by millions of people lived isolated behind an ideological wall, forcedly kept within the Utopia of a social experiment. The ‘brave new world’ of state controlled bureaucratic planned economy was based on state property instead of private and restric- tions instead of initiative. Advertising, as well as Competition and Consumerism, were all derogatory words stigmatizing the world outside the Wall – the world of Capitalism, Imperialism and Coca Cola. On the borderline where the two antagonistic worlds met, a weird phenomenon occurred – the Com Ads. This was comrade copywriter’s attempt to peep from behind the wall and present the socialist utopia as a normal part of the world. Welcome to comrade copywriter’s brave new world! Marketing - in a strictly controlled and anti-market oriented society. Branding - of deficient or even non-existant products, in the situation of stagna- tion and crisis; you could watch a Trabi TV ad every day and still wait for 15 years to bye one. -

Securitas Im Perii

Ulrich Ferdinand Kinsky: A Nobleman, Aviator, Racing Driver and Sportsman in the 20th Century Michal Plavec Ulrich Ferdinand Kinsky (15 August 1893 – 19 December 1938) came from a noble Czech family but, unlike many of his relatives, sided with the Nazis and played a key role during Lord Runciman’s mission to Czechoslovakia in 1938. He embraced the Munich Agreement and was happy to see his farm near Česká Kamenice becoming part of Nazi Germany. He died in Vienna before World War II started. It is a lesser known fact that he served in the Austro‑Hungarian Air Force during the Great War, first as an observer and later as a pilot. Flying was his great passion; he owned three airplanes and often flew them all over Europe between the two wars. He had private airports built near the manors on his property – in Klešice near Heřmanův Městec and in Dolní Kamenice near Česká Kamenice. He also served as the President of Aus‑ tria Aero Club. He was even a successful race car driver in the 1920s and remained a passionate polo player until death. Although he was the progeny of the youngest son of the 7th Prince Kinsky, he became the 10th Prince Kinsky after the death of his two uncles and father. In addition to a palace in Vienna and the two aforementioned farming estates, he also owned large farms in Choceň, Rosice and Zlonice. Kinsky divorced his first wife Katalina née Szechényi likely because he believed she was guilty of the premature death of their son Ulrich at age eleven. -

Arab Students Inside the Soviet Bloc : a Case Study on Czechoslovakia During the 1950S and 60S

European Scientific Journal June 2014 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 ARAB STUDENTS INSIDE THE SOVIET BLOC : A CASE STUDY ON CZECHOSLOVAKIA DURING THE 1950S AND 60S Daniela Hannova, MA Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts, Department of World History Abstract The paper focuses on the phenomenon of students from the so-called less developed countries in communist Czechoslovakia, specifically Arab students in the 50s and 60s of the twentieth century. The first part of the paper focuses on a broader political and social context. Because it was the first wave of Arab scholarship holders supported by the Czechoslovak government to arrive at the end of the 50s, it is crucial to describe the shape of negotiations between the Czechoslovak and Arab sides. The second part of the paper emphasizes cultural agreements and types of studying in Czechoslovakia. Arriving abroad, preparatory language courses, everyday life of Arab students in Czechoslovakia and the conflicts they had faced are analyzed in the following subchapters. The problem of Arab student adaptation to the new environment and troubles caused by cultural differences are illuminated in the framework of these thematic sections. The final part of the paper outlines the Arab absolvents’ fates and their contacts with Czechoslovakia after ending their university studies and returning to their homeland. Keywords: Students, universities, Czechoslovakia after 1948, Communism, everyday life, cultural history Introduction The phenomenon of students from the so-called less developed countries in the Soviet Bloc is a part of history, where a lot of topics and possible methodological approaches meet. -

44H5r8sz.Pdf

UC Berkeley Other Recent Work Title Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/44h5r8sz Author Zatlin, Jonathan R Publication Date 2007-04-28 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Making and Unmaking Money: Economic Planning and the Collapse of East Germany Jonathan R. Zatlin Boston University During the 1970s, a joke circulated in the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, that deftly paraphrases the peculiar problem of money in Soviet-style regimes. Two men, eager to enrich themselves by producing counterfeit bank notes, mistakenly print 70-mark bills. To improve their chances of unloading the fake notes without getting caught, they decide to travel to the provinces. Sure enough, they find a sleepy state-run retail outlet in a remote East German village. The first forger turns to his colleague and says, “Maybe you should try to buy a pack of cigarettes with the 70-mark bill first.” The second counterfeiter agrees, and disappears into the store. When he returns a few minutes later, the first man asks him how it went. “Great,” says the second man, “they didn’t notice anything at all. Here are the cigarettes, and here’s our change: two 30-mark bills and two 4-mark bills.”1 Like much of the black humor inspired by authoritarian rule, the joke makes use of irony to render unlike things commensurate. This particular joke acquires a subversive edge from its equation of communism with forgery. The two men successfully dupe the state-run store into accepting their phony bills, but the socialist state replies in kind by passing on equally fake money. -

Puolalaisten Näkemys Kuluttajuudesta Neuvostoliitossa

Puolalaisten näkemys kuluttajuudesta Neuvostoliitossa M i l a O i v a kuinka nouseva kulutuskulttuuri muovasi kaupan toimintatapoja. Tarkastelemalla Neuvostoliiton kuluttajia juuri puolalaisten ulkomaankaupan toimijoiden kautta on mahdollista kartoittaa kuinka toisen sosialistisen valtion myyjät, jotka eivät olleet vastuussa ideologisten tavoitteiden saavuttamisesta vaan ennen kaikkea myynnistä, näkivät kulutuskulttuuriin kehittymisen Neuvos- toliiton markkinoilla. Tutkin tässä artikkelissa kuluttajien paino- arvon kasvua Neuvostoliitossa puolalaisten Toisin kuin kotimaassa, jossa on myyjän mark- valmisvaateviejien käsitysten kautta 1960-luvun kinat, ulkomaankaupassa joudumme tekemisiin alusta 1970-luvun alkuun. Puolan valtiollista tyypillisten ostajan markkinoiden kanssa. On vaateteollisuutta koordinoineen Vaateteolli- äärimmäisen tärkeää että kiinnitämme huomiota suusyhtymän1 ja ulkomaankauppaministeriön vientituotteiden laatuun pysyäksemme mukana alaisuudessa toimineiden ulkomaankauppa- kilpailussa. yhtiöiden2 sisäinen kirjeenvaihto ja raportit (Lainaus Puolan ulkomaankauppaministeriön kuvasivat neuvostoliittolaisten tukkuostajien ja tavaravaihto-osaston Puolan ja Neuvostoliiton kuluttajien makutottumuksia ja niiden muutok- välistä kauppaa käsitelleestä raportista 1968, osa sia. Näitä alkuperäislähteitä käyttäen selvitän, II, 2.) millaisina puolalaiset valmisvaateviejät näkivät neuvostomarkkinat: kenen mielipide – tukkuos- Puolalaiset valmisvaateviejät markkinoivat ener- tajien, vaateammattilaisten vai kuluttajien – oli gisesti tuotteitaan -

The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989

The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989 by Mark Aaron Keck-Szajbel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor John Connelly, Chair Professor David Frick Professor Yuri Slezkine Professor Jason Wittenberg Fall 2013 The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989 Copyright © 2013 by Mark Aaron Keck-Szajbel Abstract The Borders of Friendship: Transnational Travel and Tourism in the East Bloc, 1972-1989 by Mark Aaron Keck-Szajbel Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor John Connelly, Chair The “borders of friendship” was an open border travel project between Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and Poland starting in 1972. The project allowed ordinary citizens to cross borders with a police-issued personal identification card, and citizens of member countries were initially allowed to exchange unlimited amounts of foreign currency. In this episode of liberalized travel – still largely unknown in the West – the number of border-crossings between member states grew from the tens of thousands to the tens of millions within a very brief period. This dissertation analyses the political, economic, social and cultural effects of this open border policy. It first clarifies what motivated authorities in Poland, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia to promote unorganized foreign tourism in the 1970s and 1980s. Then, it explores how authorities encouraged citizens to become tourists. Governments wanted the “borders of friendship” to be successful, but they were unsure how to define success. -

Power, Ideology and Children: Socialist Childhoods in Czechoslovakia

ISSN: 2325-3290 (online) Power, ideology and children: Socialist childhoods in Czechoslovakia Marek Tesar The University of Auckland, New Zealand Abstract There was not one, singular childhood in socialist Czechoslovakia, but many and diverse, plural, childhoods. Spanning over 40 years (1948–1989), the Czechoslovak communist governance produced diverse conceptualisations of childhoods that remain often invisible, unexplored, and the current analyses are at best sketchy and refer mostly to pedagogical nuances of strong ideological pedagogical struggles. One way to explore such an abundance of historical data in a short journal article is to utilise a somewhat personal narrative of a child. This dialogic approach allows the strong presence of the voice of a child, re-told from an adult’s perspective, and it methodologically justifies an approach to thinking and theorising of socialist childhoods through Vaclav Havel’s (1985; 1989; 1990) theoretical thinking that has been utilised in philosophy of education previously (see Tesar, 2015e). There are also other examples of complex and thorough analyses of socialist childhoods in other countries (see for example Aydarova et al, 2016), and theoretical thinking about the socialist child as a foreigner to its own land, can be done through Kristeva’s lens (Arndt, 2015). Marek Tesar is a senior lecturer in childhood studies and early childhood education at the University of Auckland. He is Editor-in-Chief of Policy Futures in Education published by SAGE, and is engaged in different editorial capacities with a number of other journals and book series. His focus is on childhood, philosophy of education, policy and methodology. Introduction There was not one, singular childhood in socialist Czechoslovakia, but many and diverse, plural, childhoods. -

Institutional Framework Around Successful Art Forms in Communist Czechoslovakia

INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK AROUND SUCCESSFUL ART FORMS IN COMMUNIST CZECHOSLOVAKIA Jan Michl Jan Michl Published in March 1999 by: OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE Open Society Institute CENTER FOR PUBLISHING Center for Publishing Development DEVELOPMENT Electronic Publishing Program ELECTRONIC PUBLISHING Október 6. u. 12 PROGRAM H-1051 Budapest Hungary www.osi.hu/ep This work was prepared under financial support from the Research Support Scheme of the Open Society Support Foundation. Research Support Scheme Bartolomějská 11 110 00 Praha 1 Czech Republic www.rss.cz The digitization of this report was supported by the Electronic Publishing Development Program and the Higher Education Support Program of the Open Society Institute Budapest. Digitization & conversion to PDF by: Virtus Libínská 1 150 00 Praha 5 Czech Republic www.virtus.cz The information published in this work is the sole responsibility of the author and should not be construed as representing the views of the Open Society Institute. The Open Society Institute takes no responsibility for the accuracy and correctness of the content of this work. Any comments related to the contents of this work should be directed to the author. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the author. Contents Introduction: summary of the research work ..........................................................................................................2 1. Failure of industrial design, success of pre-industrial arts..................................................................................4 2. The true strength of the Socialist system: redistributive power ........................................................................13 3. Contemporary lack of research interest in art institutions of the former Communist regime ...........................15 4. The Socialist idea of art ....................................................................................................................................21 5.