2The First Six Generations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Responsabile Area Tecnica

PUBBLICAZIONE AI SENSI DELL’ART. 11 COMMA 8 LETT. F) DEL D.LGS N. 150 DEL 2009 CURRICULUM VITAE Frigerio Alessandro . Nato a Como (Co) il 10/09/1960. Nazionalità: italiana RECAPITI C/O COMUNE DI CANZO Tel . 031/674123 - Fax : 031/674120 - e-mail : [email protected] TITOLI DI STUDIO E ABILITAZIONI Diplomato presso l’I.T.I.S. Magistri Cumacini di Como con votazione 50/60. Abilitato all’esercizio della professione di perito industriale edile dal 1981 iscritto all’albo professionale al n. 907 sino al 1994. Laureato in architettura presso il Politecnico di Milano con tesi di laurea in progettazione architettonica “L’università comasca nel sistema delle città pedemontane lombarde”, con votazione 96/100. Abilitato all’esercizio della professione di architetto, tramite l’Esame di Stato ed iscritto all’Ordine degli Architetti della Provincia di Como dal 1994 al n. 1408. Iscritto all’Albo dei Consulenti tecnici del Tribunale di Como dal 1990. Abilitato come esperto in materia ambientale e paesistica dal 1999. Abilitato come coordinatore per la progettazione e per l’esecuzione dei lavori in materia di sicurezza nei cantieri D.Lgv. 14 ago. 1996 n. 494 (ora D.Lgv. 81/2008). Abilitato come tecnico certificatore energetico degli edifici DGR VIII/5773 2007. Abilitato come responsabile dei servizi di prevenzione e protezione RSPP D.Lgv. 81/2008. ESPERIENZE PROFESSIONALI Collaborazione, durante il periodo scolastico, con lo studio di ingegneria civile del dott. ing. Manlio Cantaluppi di Como, negli anni 1979 – 1980 – 1981. Collaborazione come professionista negli studi di ingegneria civile del dott. ing. Manlio Cantaluppi e del dott. -

Parco Lago Segrino D.P.G.R.L

PARCO LAGO SEGRINO D.P.G.R.L. N° 602 / EC 6/12/84 Regione Lombardia Provincia di Como CONSORZIO DI COMUNI: EUPILIO, CANZO, LONGONE.AL SEGRINO COMUNITA' MONTANA TRIANGOLO LARIANO SEDE: VIA VITTORIO VENETO 16 22035 CANZO(CO) [email protected] LIDO DI AQUILEGIA-DESCRIZIONE DEL COMPLESSO E LINEE GENERALI DI INTERVENTO DA PARTE DEL GESTORE PREMESSA La struttura ricettiva denominata “Lido AQUILEGIA” (Lido d'ora in poi) è ubicata in Comune di Eupilio, per l’esercizio di tutte le attività ricreative e di ristoro connesse. Il Parco Lago Segrino, in qualità di Consorzio ed in collaborazione con il Comune di Eupilio Canzo e Longone al Segrino, ha avviato l’iter per l'affidamento in concessione del Lido per un periodo di anni 15, tenendo conto dei necessari interventi di manutenzione previsti. La succitata struttura ricettiva, ubicata su area demaniale in concessione al Comune di Eupilio, è costituita da: a) porzione di area nuda (camminamenti e percorsi esterni, terrazza, spiaggia, verde) costituita da ingresso con terrazzo e percorsi esterni terrazza a lago, area spiaggia scivolo a lago b) fabbricato (Blocco 1 ) costituito da chiosco-bar, cucina, servizi, c) fabbricato (Blocco 2 ) costituito da cabine-spogliatoio, servizi igienici docce esterne; d) pontile Per un’illustrazione più dettagliata si rinvia alle tavole grafiche messe a disposizione su supporto informatico. La struttura è stata costruita nell'anno 2004. Parte degli arredi, l'attrezzatura per la spiaggia come ombrelloni, sdraio, tavolini sono di proprietà del gestore uscente che dovrà rimuoverle alla scadenza del contratto, salvo accordi con l'eventuale nuovo gestore. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI nome CUFALO NICOLO’ data di nascita 02/01/1956 qualifica SEGRETARIO COMUNALE - FASCIA “A” (Abilitato per i Comuni con più di 65000 abitanti) incarico attuale SEGRETARIO COMUNALE DELLA SEDE CONVENZIONATA CERMENATE – VERTEMATE CON MINOPRIO numero telefonico 03188881213 e-mail [email protected] TITOLI DI STUDIO E PROFESSIONALI ED ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE Titolo di studio Laurea in Giurisprudenza conseguita presso l’Università di Palermo nell’anno 1981 con il voto di 105/110 Altri titoli di studio e Diploma Ministero dell’Interno Corso di Studi per Aspiranti professionali Segretari Comunali conseguito presso l’Università di Milano nell’anno 1984 con il voto di 54/60 Esperienze Segretario Comunale F.R c/o Comune di Vescovana (PD). Classe 4^ dal 20.12.1984 professionali al 01.07.1985. Segretario Comunale F.R. c/o Comune di Barbona (PD) Classe 4^ dal 04.07.1985 al 05.08.1985. Segretario Comunale F.R. c/o Segreteria Consorziata Vezza d’Oglio – Incudine (BS) Clase 4^ dal 05.08.1985 al 07.10.1987 Segretario Comunale in ruolo c/o Segreteria Consorziata Santa Maria Rezzonico – Sant’Abbondio (COMO) Classe 4^ dal 08.10.1987 al 15.06.1992 Reggenza Segretria Consorziata Dongo – Stazzona (CO) Classe 3^ dal 10.12.1989. al 20.06.1991 e dal 24.04.1992 al 15.06.1992 Segretario Capo dal 09.10.1989. Segretario Capo titolare Segreteria Consorziata Dongo- Sant’Abbondio (CO) classe 3^ dal 16.06.1992 al 31.01.1997 Segretario Capo titolare Comune di Dongo (CO) Classe 3^ dal 01.02.1997 al 13.05.1998. -

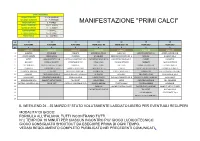

Primi Calci" Quarta Giornata 10 – 11 Marzo Quinta Giornata 17 – 18 Marzo Sesta Giornata 7 – 8 Aprile Settima Giornata 14 – 15 Aprile Festa Finale 21 – 22 Aprile

DATE CALENDARIO PRIMA GIORNATA 17 – 18 FEBBRAIO SECONDA GIORNATA 24 – 25 FEBBRAIO TERZA GIORNATA 3 -4 MARZO MANIFESTAZIONE "PRIMI CALCI" QUARTA GIORNATA 10 – 11 MARZO QUINTA GIORNATA 17 – 18 MARZO SESTA GIORNATA 7 – 8 APRILE SETTIMA GIORNATA 14 – 15 APRILE FESTA FINALE 21 – 22 APRILE sq 11 11 11 13 12 15 14 anno PURA 2009 PURA 2009 PURA 2009 MISTA 2010 - 09 MISTA 2010 - 09 PURA 2010 PURA 2010 gr 1 2 3 1 2 1 2 gruppo 01 gruppo 02 gruppo 03 gruppo 04 gruppo 05 gruppo 06 gruppo 07 1 ALBATESE ROVELLESE CABIATE ACCADEMIA COMO ALBAVILLA ARDOR LAZZATE SQ. A ARDOR LAZZATE SQ.B 2 ARDOR LAZZATE BREGNANESE CDG ERBA BINAGHESE SERENZA CARROCCIO SQ. A BRENNA BULGARO SQ.A 3 ASTRO ARDOR LAZZATE SQ.B CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ,C CACCIATORI DELLE ALPI A CACCIATORI DELLE ALPI C CABIATE CASNATESE 4 BULGARO ESPERIA LOMAZZO GERENZANESE SQ.C CAVALLASCA CASSINA RIZZARDI CARIMATE CASSINA RIZZARDI 5 CDG VENIANO CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ.B LENTATESE ERACLE SPORT CDG ERBA MONTESOLARO SQ.A ESPERIA LOMAZZO 6 CASNATESE GERENZANESE SQ.B MONTESOLARO SQ.B F.M PORTICHETTO COMETA CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ.A FALOPPIESE RONAGO 7 FALOPPIESE RONAGO HF CALCIO ORATORIO FIGINO SQ.B GUANZATESE ERACLE SPORT SQ. B MONGUZZO CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ.B 8 FENEGRO’ MONTESOLARO SQ.A PALAEXTRA SPORT ACADEMY HF CALCIO FENEGRO’ ORATORIO FIGINO GERENZANESE SQ.A 9 MASLIANICO ORATORIO FIGINO SQ.A ROVELLESE SQ.B JUNIOR CALCIO SERENZA CARROCCIO SQ. B PALAEXTRA SPORT ACADEMY MASLIANICO 10 GERENZANESE SQ.A SALUS ET VIRTUS TURATE TAU SPORT LARIOINTELVI ASTRO MONTESOLARO SQ.B POL. -

Adi Merone – Ente Gestore Cooperativa Sociale Quadrifoglio S.C

ENTI EROGATORI ADI Distretto Brianza • PAXME ASSISTANCE • ALE.MAR. COOPERATIVA SOCIALE ONLUS Como (CO) Via Castelnuovo, 1 Vigevano (PV) Via SS. Crispino e Crispiniano, 2 Tel. 031.4490272 / 340.2323524 Tel. 0381/73703 – fax 0381/76908 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Anche cure palliative • PUNTO SERVICE C/O RSA Croce di Malta • ASSOCIAZIONE A.QU.A. ONLUS Canzo (CO) Via Brusa, 20 Milano (MI) Via Panale, 66 Tel. 346.2314311 - fax 031.681787 Tel. 02.36552585 - fax 02.36551907 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] • SAN CAMILLO - PROGETTO ASSISTENZA s.r.l. • ASSOCIAZIONE ÀNCORA Varese (VA) Via Lungolago di Calcinate, 88 Longone al Segrino (CO) Via Diaz, 4 Tel. 0332.264820 - fax 0332.341682 Tel/fax 031.3357127 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Anche cure palliative Solo cure palliative • VIVISOL Solo per i Comuni di: Albavilla, Alserio, Alzate Sesto San Giovanni (MI) Via Manin, 167 Brianza, Anzano del Parco, Asso, Barni, Caglio, Tel. 800.990.161 – fax 02.26223985 Canzo, Caslino d’Erba, Castelmarte, Civenna, e-mail: [email protected] Erba, Eupilio, Lambrugo, Lasnigo, Longone al Anche cure palliative Segrino, Magreglio, Merone, Monguzzo,Orsenigo, Ponte Lambro, Proserpio, Pusiano, Rezzago, Sormano, Valbrona. • ATHENA CENTRO MEDICO Ferno (VA) Via De Gasperi, 1 Tel. 0331.726361 – Fax 0331.728270 e-mail: [email protected] Anche cure palliative • ADI MERONE – ENTE GESTORE COOPERATIVA SOCIALE QUADRIFOGLIO S.C. ONLUS Merone (CO) Via Leopardi, 5/1 Tel 031.651781 - 329.2318205 -

Volley Spettacolo a Eupilio Incoronate Le Campionesse

LapaginadelCsi PAGINA A CURA DEL COMITATO CSI COMO CSI, Como - Via del Lavoro, 4 - 22100 Como - telefono 031.5001688 - Fax 031.509956 - e-mail [email protected] - sito internet www.csicomo.it EVENTI Gazzetta Cup 2016 Volley spettacolo a Eupilio Fase Cittadina Incoronate le campionesse CSI Finali campionato. Domenica 8 maggio i verdetti per Under 14, Allieve e Open femminile Si laureano campioni provinciali il GSO Novedrate, il Valsanagra e la Polisportiva S. Agata Domenica 15 maggio, presso il Centro Sprtivo Toto Caimi di Cantù, si svolgerà la Fase Cittadi- a Tante emozioni nel na di Gazzetta Cup, il più pomeriggio di domenica 8 famoso torneo di calcio maggio con le finalissime del per ragazzi dai 9 ai 12 an- volley lariano. Presso le pale- ni. A partire dalle 9 del stre di Eupilio e la vicina pale- del mattino e fino alle 13 stra di Longone Al Segrino so- si affronterenno le 16 no scese in campo in contem- squadre qualificate per poranea le migliori 4 forma- la categoria Junior e per zioni delle categorie Under 14, la categoria Young. Nel Allieve e Open Femminile per pomeriggio spazio alle conquistare l’ambito titolo di finali che decreteranno i campione provinciale e il pass nomi delle due squadre per la fase regionale. che voleranno all’Olim- Un pomeriggio di sport tutto pico di Roma per la fina- da gustare che ha visto trionfa- La formazione del GSO Niovedrate, campione provinciale Under 14 Le ragazze del Valsanagra, campionesse provinciali Allieve le nazionale. re per la categoria Under 14 il GSO Novedrate. -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Bus

Orari e mappe della linea bus C49 C49 Asso Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus C49 (Asso) ha 7 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Asso: 06:55 - 18:35 (2) Asso FN: 06:10 - 17:35 (3) Como: 06:30 - 17:34 (4) Erba: 05:30 - 15:42 (5) Eupilio -> Lecco: 06:45 (6) Longone: 14:20 (7) Longone: 07:50 - 15:33 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus C49 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus C49 Direzione: Asso Orari della linea bus C49 33 fermate Orari di partenza verso Asso: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 06:55 - 18:35 martedì 06:55 - 18:35 Como - Stazione Trenord 3 Largo Giacomo Leopardi, Como mercoledì 06:55 - 18:35 Como - Popolo (Via Dante) giovedì 06:55 - 18:35 7 Piazza del Popolo, Como venerdì 06:55 - 18:35 Como - Via Dottesio 8/10 sabato 07:35 - 15:15 Via Luigi Dottesio, Como domenica Non in servizio Como - S. Martino (Extraurbana) 29 Via Briantea, Como Como - Crotto Del Sergente (Lora) Informazioni sulla linea bus C49 Como - Lora (Supermercato) Direzione: Asso Strada della Cappelletta, Como Fermate: 33 Durata del tragitto: 45 min Lipomo - Stabilimento Stacchini La linea in sintesi: Como - Stazione Trenord, Como - Popolo (Via Dante), Como - Via Dottesio 8/10, Como Lipomo - Bivio Paese (Rondò) - S. Martino (Extraurbana), Como - Crotto Del SPexSS342, Lipomo Sergente (Lora), Como - Lora (Supermercato), Lipomo - Stabilimento Stacchini, Lipomo - Bivio Tavernerio - Hotel Europa Paese (Rondò), Tavernerio - Hotel Europa, Tavernerio - S.S. Briantea (Incrocio), Albese - Viale Lombardia, Tavernerio - S.S. -

CANTU 2016.Indd

1 2 IN QUESTO NUMERO N° 193 - GENNAIO 2016 LA NOSTRA TERRA: BELLA, OPEROSA E RICCA DI STORIA Siamo in un luogo fantastico de “La Nostra Terra”. Ci piace dire così, per un senso di appartenenza alle no- stre radici, alla nostra storia, alle tradizioni forti che la ca- ratterizzano. Terra carica di testimonianze che risalgono all’origine dell’uomo e percorrono tutte le tappe: dai Romani ai Visconti no ai giorni nostri. Terra da scoprire nelle sue origini, con la cornice stupenda delle pianu- re, dei umi, dei castelli e dell’arte che la circonda. E con la straordinaria capacità dell’uomo di trasformare il territorio in un unicum: come è accaduto proprio nei comuni raccolti in questa pubblicazione, dove l’abilità dei contadini e la costanza delle famiglie ne hanno fat- to un caposaldo del nostro Paese. Così nasce questo capitolo che raccoglie la storia e le eccellenze del terri- torio di Cantù e dei Comuni limitro . Una guida ricca di riferimenti storici, numeri utili, appuntamenti ed eventi. Ma anche un’innovativa guida alle attività commercia- li, con rubriche ricche di suggerimenti e di consigli sulla cucina, sulla casa e sulla salute e il benessere. L’Euro- pea Editoriale considera fondamentale questo lavoro di ricerca e di comunicazione che si traduce in pubbli- cazioni che vengono offerte agli abitanti della zona e ai turisti. L’Editore e i suoi collaboratori vogliono esprimere il ringraziamento e la gratitudine innanzi tutto agli impren- ditori che hanno il coraggio di scommettere su se stessi e sul loro territorio. L’Editore Giusi Suf a I dati personali e le attività sono state pubblicate in conformità alla legge 675/96, con il 3 ne di pubblicizzare le attività e le iniziative delle pubblicazioni della Europea Editoriale. -

2019. Relazione Annuale Sullo Stato Della Pianificazione Lombarda

OSSERVATORIO PERMANENTE DELLA PROGRAMMAZIONE TERRITORIALE 2019. RELAZIONE ANNUALE SULLO STATO DELLA PIANIFICAZIONE LOMBARDA 200713OSS Maggio 2020 2019. RELAZIONE ANNUALE SULLO STATO DELLA PIANIFICAZIONE LOMBARDA OSSERVATORIO PERMANENTE DELLA PROGRAMMAZIONE TERRITORIALE 2019. RELAZIONE ANNUALE SULLO STATO DELLA PIANIFICAZIONE LOMBARDA Relazione finale promossa dalla Giunta Regionale nell’ambito del programma di attività 2019 degli Osservatori trasferiti a PoliS-Lombardia ai sensi della d.g.r. n. 2051/2011 (Codice PoliS-Lombardia: 200713OSS) Regione Lombardia, Giunta regionale Direzione Generale Territorio e Protezione Civile Fabio Conzi (Dirigente di riferimento Osservatorio della Programmazione Territoriale), Maurizio Federici, Lucia Paolini, Dario Fossati, Roberto Laffi Direzione Generale Agricoltura, Alimentazione e Sistemi Verdi Marco Armenante Gruppo di lavoro tecnico Matteo Masini (referente operativo dell’Osservatorio della Programmazione Territoriale) CAPITOLO 1 – Marina Credali, Antonella Pivotto, Sara pace, Sergio Perdiceni, Umberto Sala CAPITOLO 2 – Sara pace, Antonella Zucca CAPITOLO 3 – Cinzia Pedrotti CAPITOLO 4 – Isabella Dall’Orto, Barbara Grosso, Chiara Penco, Sandra Zappella CAPITOLO 5 – Chiara Penco, Sandra Zappella CAPITOLO 6 – Chiara Penco, Sandra Zappella CAPITOLO 7 – Sergio Perdiceni, Carolina Semeraro CAPITOLO 8 – Matteo Masini, Sergio Perdiceni, Carolina Semeraro, Giuseppe Sughero CAPITOLO 9 – Marina Credali CAPITOLO 10 – Silvia Barbugian Negro, Carolina Semeraro CAPITOLO 11 – Sara Pace CAPITOLO 12 – Matteo Masini, Luca Rossi CAPITOLO 13 – Mila Campanini, Marina Credali CAPITOLO 14 – Francesca De Cesare, Francesco Monzani CAPITOLO 15 – Matteo Masini, Silvia Montagnana, Antonella Sacco CAPITOLO 16 – Carmelo Cicala PoliS-Lombardia Dirigente di riferimento: Raffaello Vignali Project Leader: Guido Gay Gruppo di ricerca: Maria Cristina Gibelli, Massimo Izzo, Emiliano Tolusso. 2 200713OSS Maggio 2020 Pubblicazione non in vendita. Nessuna riproduzione, traduzione o adattamento può essere pubblicata senza citarne la fonte. -

Manifestazione "Primi Calci"

DATE CALENDARIO PRIMA GIORNATA 17 – 18 FEBBRAIO SECONDA GIORNATA 24 – 25 FEBBRAIO TERZA GIORNATA 3 -4 MARZO MANIFESTAZIONE "PRIMI CALCI" QUARTA GIORNATA 10 – 11 MARZO QUINTA GIORNATA 17 – 18 MARZO SESTA GIORNATA 7 – 8 APRILE SETTIMA GIORNATA 14 – 15 APRILE FESTA FINALE 21 – 22 APRILE sq 11 11 11 13 12 15 14 anno PURA 2009 PURA 2009 PURA 2009 MISTA 2010 - 09 MISTA 2010 - 09 PURA 2010 PURA 2010 gr 1 2 3 1 2 1 2 gruppo 01 gruppo 02 gruppo 03 gruppo 04 gruppo 05 gruppo 06 gruppo 07 1 ALBATESE ROVELLESE CABIATE ACCADEMIA COMO ALBAVILLA ARDOR LAZZATE SQ. A ARDOR LAZZATE SQ.B 2 ARDOR LAZZATE BREGNANESE CDG ERBA BINAGHESE SERENZA CARROCCIO SQ. A BRENNA BULGARO SQ.A 3 ASTRO ARDOR LAZZATE SQ.B CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ,C CACCIATORI DELLE ALPI A CACCIATORI DELLE ALPI C CABIATE CASNATESE 4 BULGARO ESPERIA LOMAZZO GERENZANESE SQ.C CAVALLASCA CASSINA RIZZARDI CARIMATE CASSINA RIZZARDI 5 CDG VENIANO CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ.B LENTATESE ERACLE SPORT CDG ERBA MONTESOLARO SQ.A ESPERIA LOMAZZO 6 CASNATESE GERENZANESE SQ.B MONTESOLARO SQ.B F.M PORTICHETTO COMETA CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ.A FALOPPIESE RONAGO 7 FALOPPIESE RONAGO HF CALCIO ORATORIO FIGINO SQ.B GUANZATESE ERACLE SPORT SQ. B MONGUZZO CASTELLO VIGHIZZOLO SQ.B 8 FENEGRO’ MONTESOLARO SQ.A PALAEXTRA SPORT ACADEMY HF CALCIO FENEGRO’ ORATORIO FIGINO GERENZANESE SQ.A 9 MASLIANICO ORATORIO FIGINO SQ.A ROVELLESE SQ.B JUNIOR CALCIO SERENZA CARROCCIO SQ. B PALAEXTRA SPORT ACADEMY MASLIANICO 10 GERENZANESE SQ.A SALUS ET VIRTUS TURATE TAU SPORT LARIOINTELVI ASTRO MONTESOLARO SQ.B POL. -

CALENDARIO Stagione 2017 - 2018 GIOVANISSIMI FASCIA B COMO – Fase Autunnale Girone B

CALENDARIO Stagione 2017 - 2018 GIOVANISSIMI FASCIA B COMO – Fase Autunnale Girone B 1a Giornata 2a Giornata 3a Giornata 23 Set 30 Set 7 Ott BREGNANESE STELLA AZZURRA AROSIO ARCELLASCO CITTA DI ERBA BREGNANESE BREGNANESE INVERIGO CARUGO ACADEMY SERENZA CARROCCIO ARDOR LAZZATE INVERIGO CARUGO ACADEMY ARCELLASCO CITTA DI ERBA G.S.O CASTELLO VIGHIZ. sq.B VALBASCA LIPOMO BULGARO SAMZ EUPILIO LONGONE G.S.O CASTELLO VIGHIZ. sq.B BULGARO INVERIGO ARCELLASCO CITTA DI ERBA ORATORIO FIGINO CALCIO G.S.O CASTELLO VIGHIZ. sq.B MONTESOLARO ORATORIO FIGINO CALCIO MONTESOLARO ARDOR LAZZATE SERENZA CARROCCIO PONTELAMBRESE PONTELAMBRESE STELLA AZZURRA AROSIO PONTELAMBRESE BULGARO STELLA AZZURRA AROSIO CARUGO ACADEMY SAMZ EUPILIO LONGONE SERENZA CARROCCIO SAMZ EUPILIO LONGONE ORATORIO FIGINO CALCIO VALBASCA LIPOMO MONTESOLARO VALBASCA LIPOMO ARDOR LAZZATE 4a Giornata 5a Giornata 6a Giornata 7a Giornata 14 Ott 21 Ott 28 Ott 4 Nov ARCELLASCO CITTA DI ERBA PONTELAMBRESE CARUGO ACADEMY BREGNANESE ARCELLASCO CITTA DI ERBA G.S.O CASTELLO VIGHIZ. sq.B BULGARO ARDOR LAZZATE ARDOR LAZZATE BREGNANESE G.S.O CASTELLO VIGHIZ. sq.B STELLA AZZURRA AROSIO ARDOR LAZZATE CARUGO ACADEMY G.S.O CASTELLO VIGHIZ. sq.B INVERIGO BULGARO MONTESOLARO MONTESOLARO SERENZA CARROCCIO BREGNANESE PONTELAMBRESE MONTESOLARO ARCELLASCO CITTA DI ERBA INVERIGO CARUGO ACADEMY ORATORIO FIGINO CALCIO ARDOR LAZZATE BULGARO ORATORIO FIGINO CALCIO ORATORIO FIGINO CALCIO SERENZA CARROCCIO ORATORIO FIGINO CALCIO VALBASCA LIPOMO PONTELAMBRESE INVERIGO INVERIGO SAMZ EUPILIO LONGONE PONTELAMBRESE CARUGO -

COMUNE DI EUPILIO Provincia Di Como

COMUNE DI EUPILIO Provincia di Como PIANO DI GOVERNO DEL TERRITORIO Legge Regionale 12/2005 DOCUMENTO DI PIANO RELAZIONE (Aprile 2011 – Agg. Giugno 2012) Dott. Arch. Giacomino Amadeo Dott. Arch. Arnaldo Falbo Ordine Architetti PPC di Monza e Brianza n. 2622 Ordine Architetti PPC di Como n. 1483 Via S. Carlo, 1 - 20811 Cesano Maderno (MB) Via Ballerini, 12 - 22100 Como (CO) Tel. +39 0362 500200 - Fax +39 0362 1580711 Tel. +39 031 241646 - Fax +39 031 4129304 [email protected] [email protected] INDICE PARTE I Sezione I - Quadro conoscitivo 1. - Luogo, paesaggi e ambienti 1.1 - Luogo storia e territorio 1.2 - Il paesaggio locale 1.3 - La struttura del paesaggio agrario 1.3.1 - Quadro conoscitivo 1.4 - Ambienti urbani e morfologia dell’edificato 1.5 - Indagini specialistiche 1.5.1 - Studio geologico e idrogeologico 1.5.2 - Definizione del reticolo idrografico minore 1.5.3 - Azzonamento acustico 2. - L’assetto infrastrutturale 2.1 - La viabilità 2.2 - Il trasporto pubblico 2.3 - I percorsi ciclabili – la Ciclovia dei Laghi 2.4 - La rete fognaria esistente 3. - L’ambiente costruito 3.1 - Il patrimonio edificato 3.2 - Il patrimonio paesaggistico e ambientale 4. - Servizi e attrezzature - pubblici e di uso pubblico 4.1 - Servizi e attrezzature pubblici 5. - Analisi demografica e socioeconomica 5.1 - Struttura e dinamica della popolazione Sezione II - Quadro ricognitivo di riferimento a) Piano Territoriale Regionale (PTR) b) Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Provinciale (PTCP) c) Parco della Valle del Lambro d) Parco Locale di Interesse Sovracomunale del Lago del Segrino e) Piano di gestione Sito di Importanza Comunitaria del Lago di Pusiano -(IT2020006) f) Piano di gestione Sito di Importanza Comunitaria del Lago del Segrino - (IT2020010) g) Piano di indirizzo Forestale della Comunità Montana del Triangolo Lariano h) Le proposte e segnalazioni dei cittadini EUPILIO-REL-DP-DEF-REV-01 - Pagina - 2 - di 141 PARTE II - Obiettivi di intervento e strategie attuative 6.