Fundamental Issues Sikh Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIKHISM Part 2 Unit 3: the Guru Granth Sahib, the Final Guru

SIKHISM Part 2 Unit 3: The Guru Granth Sahib, The Final Guru What this unit contains There were 10 human Gurus. The Guru Granth Sahib, the final Guru - its contents, use and central place in the Gurdwara. Akhand Path – special reading of the Guru Granth Sahib. Beliefs taught through the Guru Granth Sahib. Where the unit fits and how it builds upon This unit builds on work covered in previous units. It extends understanding about the contents, use previous learning and significance of the Guru Granth Sahib. Extension activities and further thinking Link the dates of the Gurus to other significant world events. Consider how it might have changed Sikhism if one of the Gurus had been a woman. Research how the Gurus lived under religious persecution. Vocabulary SMSC/Citizenship Ik Onkar sacred text Mool Mantra Granthi Equality of all - gender, race and creed. Guru Akhand Path Guru Gobind Singh immortal Beliefs about creation. Sikh Gurmurkhi Guru Granth Sahib Gurdwara Beliefs in a divine creator. Sikhism Having a personal set of beliefs and values. Lambeth Agreed Syllabus for Religious Education Teaching unit SIKHISM Part 2 Unit 3:1 Unit 3: The Guru Granth Sahib, The Final Guru SIKHISM Part 2 Unit 3 Session 1 A A Learning objectives T T Suggested teaching activities Sensitivities, points to note, 1 2 resources Pupils should: Before the lesson set up a Guru Timeline with details / biographies of Resources √ each on handouts and blank Guru information sheets on which to Poster / picture of the Gurus. know the chronology record collected information for Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh 'Celebrate Sikh festivals' and names of the 10 and sheets with detailed information about the remaining Gurus. -

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib As the Only Sikh Canon

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib as the only sikh canon (From www.GlobalSikhStudies.net) Jasbir Singh Mann M.D., California. The lineage of Personal Guruship was terminated ( Canon Closed) on October, 6th Wednesday1708 A.D. by the 10th Guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, after finalizing the sanctification of Guru Nanak’s Mission and passing the succession to Guru Granth Sahib as future Guru of the Sikhs. This was the final culmination of the Sikh concept of Guruship, capable of resisting the temptation of continuation of the lineage of human Gurus. The Tenth Guru while maintaining the concept of ‘Shabad Guru’ also made the Panth distinctive by introducing corporate Guruship. The concept of Guruship continued and the role of human gurus was transferred to the Guru Panth and that of the revealed word to Guru Granth Sahib making Sikhism a unique modern religion. This historical fact is well documented in Indian, Persian and Western Sikh sources of 18th century. Indian sources: Sainapat (1711), Bhai Nand Lal, Bhai Prahlad, and Chaupa Singh, Koer Singh (1751), Kesar Singh Chhibber (1769-1779Ad), Mehama Prakash (1776), Munshi Sant Singh ( on account of Bedi family of the Ulna, Unpublished records), Bhatt Vahi’s. Persian sources: Mirza Muhammad (1705-1719 AD), Sayad Muhammad Qasim (1722 AD), Hussain Lahauri(1731), Royal Court News of Mughals, Akhbarat-i-Darbar-i-Mualla (1708). Western sources: Father Wendel, Charles Wilkins, Crauford, James Browne, George Forester, and John Griffith. These sources clearly emphasize the tenets of Nanak as enshrined in Guru Granth Sahib as the only promulgated scripture of the Sikhs. -

Guru Tegh Bahadur

Second Edition: Revised and updated with Gurbani of Guru Tegh Bahadur. GURU TEGH BAHADUR (1621-1675) The True Story Gurmukh Singh OBE (UK) Published by: Author’s note: This Digital Edition is available to Gurdwaras and Sikh organisations for publication with own cover design and introductory messages. Contact author for permission: Gurmukh Singh OBE E-mail: [email protected] Second edition © 2021 Gurmukh Singh © 2021 Gurmukh Singh All rights reserved by the author. Except for quotations with acknowledgement, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or medium without the specific written permission of the author or his legal representatives. The account which follows is that of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Nanak IX. His martyrdom was a momentous and unique event. Never in the annals of human history had the leader of one religion given his life for the religious freedom of others. Tegh Bahadur’s deed [martyrdom] was unique (Guru Gobind Singh, Bachittar Natak.) A martyrdom to stabilize the world (Bhai Gurdas Singh (II) Vaar 41 Pauri 23) ***** First edition: April 2017 Second edition: May 2021 Revised and updated with interpretation of the main themes of Guru Tegh Bahadur’s Gurbani. References to other religions in this book: Sikhi (Sikhism) respects all religious paths to the One Creator Being of all. Guru Nanak used the same lens of Truthful Conduct and egalitarian human values to judge all religions as practised while showing the right way to all in a spirit of Sarbatt da Bhala (wellbeing of all). His teachings were accepted by most good followers of the main religions of his time who understood the essence of religion, while others opposed. -

Of Our 10Th Master - Dhan Guru Gobind Singh Ji Maharaj

TODAY, 25th December 2017 marks the Parkash (coming into the world) of our 10th master - Dhan Guru Gobind Singh Ji Maharaj. By dedicating just 5 minutes per day over 4 days you will be able to experience this saakhi (historical account) as narrated by Bhai Vishal Singh Ji from Kavi Santokh Singh Ji’s Gurpartap Suraj Granth. Please take the time to read it and immerse yourselves in our rich and beautiful history, Please share as widely as possible so we can all remember our king of kings Dhan Guru Gobind Singh Ji on this day. Let's not let today pass for Sikhs as just being Christmas! Please forgive us for any mistakes. *Some background information…* When we talk about the coming into this world of a Guru Sahib, we avoid using the word ‘birth’ for anything that is born must also die one day. However, *Satgur mera sada sada* The true Guru is forever and ever (Dhan Guru Ramdaas Ji Maharaj, Ang 758) Thus, when we talk about the coming into the world of Guru Sahibs we use words such as Parkash or Avtar. This is because Maharaj are forever present and on this day They simply became known/visible to us. Similarly, on the day that Guru Sahib leave their physical form, we do not use the word death because although Maharaj gave up their human form, they have not left us. Their jot (light) was passed onto the next Guru Sahib and now resides within Dhan Guru Granth Sahib Ji Maharaj. So, you will often hear people say “Maharaj Joti Jot smaa gai” meaning that their light merged back into the light of Vaheguru. -

Banda Bahadur

=0) |0 Sohan Singh Banda the Brave ^t:- ;^^^^tr^ y^-'^;?^ -g^S?^ All rights reserved. 1 € 7?^ ^jfiiai-g # oft «3<3 % mm "C BANDA THE BRAVE BY 8HAI SOHAN SINfiH SHER-I-BABAE. Published by Bhai NARAiN SINGH Gyani, Makaqeb, The Puiyabi Novelist Co,, MUZAm, LAHORE. 1915. \^t Edition?^ 1000 Copies. [Pmy 7 Hupef. 1 § J^ ?'Rl3]f tft oft ^30 II BANDA THE BRAVE OR The Life and Exploits OF BANDA BAHADUB Bliai SoJiaii Siiigli Shei-i-Babar of Ciiijrainvala, Secretarv, Office of the Siiperiiitendeiit, FARIDKOT STATE. Fofiuerly Editor, the Sikhs and Sikhism, and ' the Khalsa Advocate ; Author of A Tale of Woe/ *Parem Soma/ &c., &c. PXJ]E>irjrABX I^O^irElL,IST CO., MUZANG, LAHORE. Ut Edition, Price 1 Rupee. PRINTED AT THE EMPIRE PRESS, LAHORE. — V y U L — :o: My beloved Saviour, Sri Guru Gobind Singh Ji Kalgi Dhar Maharaj I You sacrificed your loving father and four darlings and saved us, the ungrateful people. As the subject of this little book is but a part and parcel of the great immortal work that you did, and relates to the brilliant exploits and achievements of your de- voted Sikhs, I dedicate it to your holy name, in token of the deepest debt of gratitude you have placed me and mine under, in the fervent hope that it may be of some service to your beloved Panth. SOHAN SINGH. FREFAOE. In my case, it is ray own family traditions that actuated me to take up my pen to write this piece of Sikh History. Sikhism in my family began with my great great grand father, Bhai Mansa Singh of Khcm Karn, Avho having received Amrita joined the Budha Dal, and afterwards accompanied Sardar Charat Singh to Giijranwala. -

Know Your Heritage Introductory Essays on Primary Sources of Sikhism

KNOW YOUR HERIGAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES , C HANDIGARH KNOW YOUR HERITAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM Dr Dharam Singh Prof Kulwant Singh INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES CHANDIGARH Know Your Heritage – Introductory Essays on Primary Sikh Sources by Prof Dharam Singh & Prof Kulwant Singh ISBN: 81-85815-39-9 All rights are reserved First Edition: 2017 Copies: 1100 Price: Rs. 400/- Published by Institute of Sikh Studies Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Kanthala, Indl Area Phase II Chandigarh -160 002 (India). Printed at Adarsh Publication, Sector 92, Mohali Contents Foreword – Dr Kirpal Singh 7 Introduction 9 Sri Guru Granth Sahib – Dr Dharam Singh 33 Vars and Kabit Swiyyas of Bhai Gurdas – Prof Kulwant Singh 72 Janamsakhis Literature – Prof Kulwant Singh 109 Sri Gur Sobha – Prof Kulwant Singh 138 Gurbilas Literature – Dr Dharam Singh 173 Bansavalinama Dasan Patshahian Ka – Dr Dharam Singh 209 Mehma Prakash – Dr Dharam Singh 233 Sri Gur Panth Parkash – Prof Kulwant Singh 257 Sri Gur Partap Suraj Granth – Prof Kulwant Singh 288 Rehatnamas – Dr Dharam Singh 305 Know your Heritage 6 Know your Heritage FOREWORD Despite the widespread sweep of globalization making the entire world a global village, its different constituent countries and nations continue to retain, follow and promote their respective religious, cultural and civilizational heritage. Each one of them endeavours to preserve their distinctive identity and take pains to imbibe and inculcate its religio- cultural attributes in their younger generations, so that they continue to remain firmly attached to their roots even while assimilating the modern technology’s influence and peripheral lifestyle mannerisms of the new age. -

The Doctrinal Inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : in Relation to Avtarhood(Part I)

The Doctrinal inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : In relation to Avtarhood(Part I) Prof.Gurnam Kaur* (A) Introduction:- This paper is concerned with the authenticity of the compositions included in the Dasam Granth or we can say with the doctrinal inconsistencies in the Dasam Granth in relation to the idea of avtarhood,i.e. incarnation of God in different forms human or any, devi pooja (worship of goddess) shastar as Pir i.e. to worship weapons as the highest spiritual person, bias against unshorn hair, supporting the use of intoxicants and bias against woman. To judge all these things we have to take the help of Sikh tenants and adopt some basic criterion or methodology because these days animated discussions are going on about the Dasam Granth. The text has already been analyzed by known scholars from the historical, religious and theological points of view. Being the student of Sikh philosophy, with due regards to the analysis already done, I will try to analyze the text in the light of Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Sri Guru Granth Sahib is the basic and primary scripture of Sikh religion. No other scripture can be considered equal to it. This is the only Scripture in the history of the world religions which was compiled by its founder Gurus themselves. The fifth Guru Arjan Dev compiled the first recension and installed it at Harmander Sahib on Bhadon sudi. I, 1604 A.D. Bhai Gurdas was the first scribe and Baba Budha Ji was made the first Granthi. Guru Gobind Singh, the Tenth and last physical Guru, added the bani composed by Guru Teg Bahadur, the ninth Nanak Joti and bestowed 1 Guruship on the Granth before his final departure in samat 1765 from this mundane world. -

Reading Writing Spoken Language Transcript Maths Science Forces

Reading Maths Science Apply knowledge of root words, prefixes and suffixes to read aloud and to Match 2-place decimals to 1/100s, using a place value grid Forces understand the meaning of unfamiliar words. Use place value to multiply and divide numbers by 10 and 100, involving 2- Read further exception words, noting the unusual correspondences between place decimals Investigation spelling and sound, and where these occur in the word. Use place value to add and subtract 0·1 and 0·01 to and from decimal Explore different ways to test an idea, choose the best way, and Become familiar with and talk about a wide range of books, including myths, numbers legends and traditional stories and books from other cultures and traditions give reasons and know their features. Use doubling and halving to multiply and divide by 4 and 8 and solve Vary one factor whilst keeping the others the same in an Read non-fiction texts and identify purpose and structures and grammatical correspondence problems experiment features and evaluate how effective they are. Use advanced mental multiplication strategies Explain why they do this Use meaning-seeking strategies to explore the meaning of words in context Add/subtract 2-digit numbers to/from 2-digit numbers by counting on/bar Plan and carry out an investigation by controlling variables fairly Add pairs of 2-digit numbers with a total ≤ 198 and accurately Writing Subtract 2-digit from 2-digit numbers by counting up Make a prediction with reasons Use number facts to 10 to solve problems including word problems Use -

Amrit Sanskar) Should Be Held at an Exclusive Place Away from Common Human Traffic

Amrit Sanchar (Ceremony of Khande di Pahul) Anyone can be initiated into the Sikh religion if one can read and understand the contents of Guru Granth Sahib and is matured enough to follow the Sikh code of conduct. The baptism ceremony is known as 'Amrit Chhakna". It is conducted. In a holy place, any place sanctified with the presence of Guru Granth Sahib, preferably a Gurdwara. The ceremony is conducted by five baptized Sikhs known as Singhs or Khalsa who must be observant of the Sikh religious discipline and the Sikh code of conduct A date and place is fixed for the baptismal ceremony and information to that effect is given in the local press. All the candidates interested in the initiation then formally apply for admission. The candidates are interviewed and if found worthy of initiation are called at the specified place at the fixed date and time. The formal ceremony is conducted in the following way: 1 Guru Granth Sahib is opened in the ceremonious way. One of the five Khalsas selected for the Amrit ceremony offers the formal prayer in the presence of Guru Granth Sahib which is followed by a random reading from the holy book. 2 The entrants join in the formal prayer and sit cross legged when the verse from Guru Granth Sahib is being read. Then they stand in front of the congregation (if there is any) and ask their permission for admission into the Khalsa brotherhood. The permission is normally given by means of the religious call-Bolay So Nihal Sat Sri Akal (Whosoever Would Speak Would Be Blessed-God Is The Supreme Truth). -

Gurdwara Guidelines

Gurdwara Guidelines Darbar Sahib (The overall Responsibility of the Darbar Sahib Management Committee) • Parkaash in the morning and Suhaassan in the evening • All prayers to be conducted by the Granthi/Jatha unless specified by MC • Gurdwara programs start with recitation of Gurbani, followed by Kirtan. • Various Gurbani Paths are done each Sunday – refer to separate Paath list. KIRTAN: • Kirtan times are 10.00 am -11.45 am on Sundays and 6:30 pm – 7:45 pm on all other days unless otherwise specified by the Committee. • Kirtan is followed by Anand Sahib, Ardaas and Hukam Naama • The local / Sangat Kirtan singers to be allocated time by DSM • If the family hosting the Langgar has a special request, they must discuss with the DSM • The last half hour of the program is allocated to the Resident Granthi/Jatha • Program to be finished within the allocated times ARDAAS: • To be done by the Resident Granthi only, unless otherwise specified by MC • Ardaas is according to the Rehat Maryada - no repetitions & unnecessary additions • Only the name of the family sponsoring the program of the day is to be read out unless requested due to special circumstances. • No monetary donations will be announced in the Ardas. • A DSM member to collect Ardaas list from Treasurer and provide to Granthi and a list with the donations to the Secretary for announcements. LANGGAR • Families hosting the function on Sunday are requested to obtain the Langgar ingredient list from the Kitchen committee Sewadaar. • Preparation for Sunday Langgar takes place on the Saturday at a time nominated by the host family. -

Baby Naming Ceremony – Naam Karan

Baby Naming Ceremony – Naam Karan Cut out the statements, read through them and see if you can arrange them in the correct order. Research ‘baby naming ceremony in Sikhism’ using the Internet to see if you were correct. When a woman first discovers she When the baby is born, the mool is pregnant, she will recite prayers If this is their first child, the parents mantra (the fundamental belief of thanking Waheguru for the gift of the may refer to the Sikh Rahit Maryada Sikhism) is whispered into the baby’s child. She will ask Waheguru for the (code of conduct) to check what the ear. A drop of honey is also placed in protection and safety of the foetus procedure is for the naam karan. the baby’s mouth. as it develops. The family brings a gift to the Gurd- Both parents (as soon as the moth- wara. It may be a rumalla (piece of er is able to), along with any family The granthi opens the Guru Granth cloth used to cover the Guru Granth member who wishes to join in on Sahib at random and reads the pas- Sahib), some food to be used in the the naam karan, will go to their local sage on that page to the sangat (con- langar or a monetary donation to Gurdwara within 40 days of the ba- gregation). put in the donation box by the manji by’s birth. granth. Once the parents have chosen the Karah Prashad (a sweet semolina The parents choose a name using baby’s first name, the granthi will mix) is then distributed to everyone, the first letter of the first word from then give the child the surname Kaur, shared out from the same bowl. -

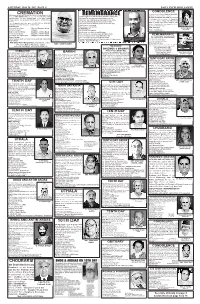

Page2.Qxd (Page 2)

SATURDAY, MAY 20, 2017 (PAGE 2) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU CONDOLENCE CREMATION In loving memory of Sardar Joginder Singh Bali, a With profound grief and sorrow we inform the sad demise of our REMEMBRANCE As we thought of you with love today, but that is nothing new, loving father, husband, brother and son. beloved SMT. VIDHYA DEVI w/o Late Sh. BALAK RAM GUPTA Aarambh Shri Akhand Path Sahib on 19-05-2017, (Gharota Wale), R/o F-25, Mohalla Baba Jeevan Shah, Shahidi We thought of you yesterday and days before that too, 9 am (Friday) at their residence 51 Gobind Lane Chowk, Jammu, now at present 57-58, Sector 3, Channi Himmat, We think of you in silence as we often speak of your name, Preet Nagar Digiana. Bhog Shri Akhand Path Jammu. All we have are memories and your pictures in frame, The Cremation shall take place at 4:00 PM on 20-05-2017 Sahib on Sunday 9 am at their residence. Antim Your memories in our keepsafe, where we will never part, Ardas at Gurudwara Shri Guru Angad Dev Ji Preet (Saturday) at Channi Himmat Cremation Ground. God has you in his keeping, Grief Stricken Nagar on 21-05-2017, 12 pm We have you in our HEARTS. GRIEF STRICKEN Arun and Renu Gupta - Son and Daughter in law REMEMBERED BY: Sardar Joginder Aman Deep Singh Bali Singh Bali Chanchala Gupta - Daughter Smt. Surinder Soni-Mother Contact : +919086140411 Sudesh and Ravi Gupta - Daughter and Son in law Anu & Suresh Soni-Sister-in-law & Brother Veena and JC Gupta - Daughter and Son in law Renu and Chander Choudhary-Sister & Brother-in-law Meenakshi and Jugal Gupta - Daughter and Son in law Neera and Deepak Gandhi-Sister & Brother-in-law REMEMBRANCE Grand Chidren Karuna and Anil Sharma-Sister & Brother-in-law ON 23RD BIRTH ANNIVERSARY Rahul Mahajan, KAS (Accounts Officer, Audit and Inspections), Premier Baked Food Industry, 32 Digiana Industrial Estate, Jammu SANJAY SONI (SUNNY) No one knows how much we miss you.