Chapter 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henri Mouhot (1826-1861) Was a French Naturalist and Explorer Born

Henri Mouhot (1826-1861) was a French naturalist and explorer born into a Protestant family on 25 May 1826 in Franche-Comté, who is renowned for his popularisation of Angkor, Cambodia. He married Ann Park, a descendant (probably a granddaughter) explorer Mungo Park, at St Marylebone in 1854 or 1855, before settling in 1856 in the island of Jersey. Mouhot spent ten years in Russia,working as a language tutor at the St Petersburg Military Academy. He travelled widely in Europe and studied photography before turning to Natural Science as the age of thirty. After a year Mouhot decided to travel to Indochina to collect new zoological specimens and eventually received the financial support of the Royal Geographical Society and the Zoological Society of London after being turned down by the French government. He sailed to Bangkok and then made several trips to Cambodia where he came across Angkor, a place consisting of sites such as ancient terraces, pools, moated cities, palaces and temples. Mouhot is often mistakenly credited with "discovering" Angkor when in fact the site had been visited by several westerners since the sixteenth century. What he did was popularize Angkor in the West as he wrote more evocatively than any previous explorers (through his illustrated journals "Voyage dans les Royaumes de Siam, de Cambodge, de Laos et Autres Parties Centrales de l'Indo-Chine" published in 1868). Although Mouhot made known his insights into this area of Cambodia, he did initially make a grave error in his dating of its formation. Because the explorer saw the Khmer inhabitants as barbaric he made the assumption that they could not have been the original settlers and so dated Angkor back over two millennia, to around the same era as Rome. -

Views of Angkor in French Colonial Cambodia (1863-1954)

“DISCOVERING” CAMBODIA: VIEWS OF ANGKOR IN FRENCH COLONIAL CAMBODIA (1863-1954) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jennifer Lee Foley January 2006 © 2006 Jennifer Lee Foley “DISCOVERING” CAMBODIA: VIEWS OF ANGKOR IN FRENCH COLONIAL CAMBODIA (1863-1954) Jennifer Lee Foley, Ph. D Cornell University 2006 This dissertation is an examination of descriptions, writings, and photographic and architectural reproductions of Angkor in Europe and the United States during Cambodia’s colonial period, which began in 1863 and lasted until 1953. Using the work of Mary Louise Pratt on colonial era narratives and Mieke Bal on the construction of narratives in museum exhibitions, this examination focuses on the narrative that came to represent Cambodia in Europe and the United States, and is conducted with an eye on what these works expose about their Western, and predominately French, producers. Angkor captured the imagination of readers in France even before the colonial period in Cambodia had officially begun. The posthumously published journals of the naturalist Henri Mouhot brought to the minds of many visions of lost civilizations disintegrating in the jungle. This initial view of Angkor proved to be surprisingly resilient, surviving not only throughout the colonial period, but even to the present day. This dissertation seeks to follow the evolution of the conflation of Cambodia and Angkor in the French “narrative” of Cambodia, from the initial exposures, such as Mouhot’s writing, through the close of colonial period. In addition, this dissertation will examine the resilience of this vision of Cambodia in the continued production of this narrative, to the exclusion of the numerous changes that were taking place in the country. -

The Cross Thai-Cambodian Border's Commerce Between 1863

ISSN 2411-9571 (Print) European Journal of Economics September-December 2017 ISSN 2411-4073 (online) and Business Studies Volume 3, Issue 3 The Cross Thai-Cambodian Border’s Commerce Between 1863 -1953 from the View of French’s Documents Nathaporn Thaijongrak, Ph.D Lecturer of Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, Srinakharinwirot University Abstract The purpose of this research aims to study and collect data with detailed information of the cross Thai- Cambodian border’s commerce in the past from French’s documents and to provide information as a guideline for potential development of Thai-Cambodian Border Trade. The method used in this research is the qualitative research. The research instrument used historical methods by collecting information from primary and secondary sources, then to analysis process. The research discovered the pattern of trade between Cambodia and Siam that started to be affected when borders were established. Since Cambodia was under French’s rule as one of French’s nation, France tried to delimit and demarcate the boundary lines which divided the community that once cohabitated into a community under new nation state. In each area, traditions, rules and laws are different, but people lived along the border continued to bring their goods to exchange for their livings. This habit is still continuing, even the living communities are divided into different countries. For such reason, it was the source of "Border trade” in western concept. The Thai-Cambodian border’s trade during that period under the French protectorate of Cambodia was effected because of the rules and law which illustrated the sovereignty of the land. -

Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China

« '-^ >:!?>! 4M ,, jinm° ^-fii Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/travelsincentral01mouh TRAVELS IN THK CENTRAL PARTS OF INDO-CHINA ( SIAM ), CAMBODIA, AND LAOS. VOL. I. B 2 Drawn by M. Bcco\irt, from a Photograph . THE KING AND QUEEN OF SIAM. : 5C5 TKAVELS •^^*^' IN THE y,| CENTRAL PARTS OF INDO-CHIM (SIAM), CAMBODIA, AND LAOS, DUEING THE YEAES 1858, 1859, AND 1860. BY THE LATE M. HENEI MOUHOT, FRENCH NATURALIST. IN TWO VOLUMES.—Vol. L WITH ILLUSTRATIONS. LONDON JOHN MUEEAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET, 1864. n )6u> v.±. LONDON: PBrNTED BT WILHASt CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFOltD STRKET, AND CHARING CROSS. DEDICATION. TO THE LEARNED SOCIETIES OF ENGLAND, WHO HAVE FAVOURED WITH THEIR ENCOURAGEMENT THE JOURNEY OF M. HENRI MOUHOT TO THE REMOTE LANDS OF SIAM, LAOS, AND CAMBODIA. I TRUST tliat tlie members of those scientific societies who kindly supported and encouraged my brother in his travels and labours, will receive favourably the documents collected by the family of the intrepid traveller, whom death carried off in the flower of his age, in the midst of his discoveries. Had he been able to accomplish fully the end at which he aimed, it would certainly have been to you that he would have offered the fruits of his travels : he would have felt it his first duty to testify his gratitude and esteem to the worthy repre- sentatives of science in that great, free, and generous English nation who adopted him. Half English by his marriage, M. Mouhot still preserved his love for his own country : there, however, for various reasons he did not receive the encourage- ment he anticipated, and it was on the hospitable soil of England that he met with that aid and support, which not only her scientific men, but the whole nation, delight in affording to explorations in unknown countries, ever attended by perils and hardships. -

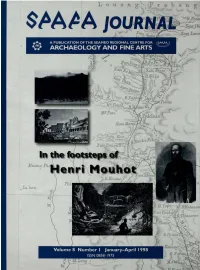

Discovery of Other Temple Ruins in Angkor • Infant Dinosaur Fossils •Holland Seize Priceless Smuggled Artifacts •'Cultural Management' Conference

SEAMEO-SPAFA Regional Centre for A r c h a e o l o g y and Fine Arts SPAFA Journal is published three times a year by the SEAMEO-SPAFA Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts. It is a forum for scholars, researchers and professionals on archaeology, performing arts, visual a r t s and cultural activities in Southeast Asia to share views, research findings and evaluations. The opinions expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of SPAFA. SPAFA's objectives : • Promote awareness and appreciation of the cultural heritage of Southeast Asian countries through preservation of archaeological and historical artifacts, and traditional arts; • Help enrich cultural activities in the region; • Strengthen professional competence in the fields of archaeology and fine arts through sharing of resources and experiences on a regional basis; • Increase understanding among the countries of Southeast Asia through collaboration in archaeological and fine arts programmes. Editorial Board Production Services Mr. Pisit Charoenwongsa Prasanna Weerawardane Mr. Elmar B. Ingles Vassana Taburi Professor Khunying Maenmas Chavalit Wanpen Kongpoon Mr. Zulkifli Mohamad Wilasinee Thabuengkarn Publication Co-ordinator Photographic Services Ean Lee Nipon Sud-Ngam Cover Photographs by Dawn Rooney Printers Amarin Printing and Publishing Public Company limited 65/16 Moo 4 Chaiyapruk Road Talingchan Bangkok 10170 Thailand Tel. 8821010 (30 Unes) Fax. 4332742, 4341385 Note for Contributors Manuscripts could be submitted in electronic form (PC or Macintosh). Related photographs or illustrations and a brief biographical paragraph describing author's current affiliation and research interests should accompany the manuscript. Annual Subscription Rates: US $27 (Air Mail) US $24 (Surface Mail) US $19/Baht 465 (Within Thailand) Cost Per Issue: US $6/Baht 150 Contact: SPAFA Regional Centre SPAFA Building 81/1 Sri Ayutthaya Road, Samsen, Theves Bangkok 10300,Thailand Tel. -

Émile Gsell (1838–79) and Early Photographs of Angkor Joachim K

JOACHIM K. BAUTZE Chapter 24 Émile Gsell (1838–79) and Early Photographs of Angkor Joachim K. Bautze Abstract The earliest photographs of Angkor in Cambodia were taken by the Scottish photographer and geogra- pher, John Thomson (1837–1921). Starting from Bangkok on 27 January 1866, “to photograph the ruined temples” (Thomson 1875: 118) Thomson journeyed to Angkor, “in consequence” as he himself admit- ted, “of the interest excited in me by reading the late M. Mouhot’s1 ‘Travels in Indo-China, Cambodia, and Laos,’2 and other works to which I had access” (Thomson 1867: 7). Thomson states that he used a “photographic apparatus and chemicals for the wet collodion process” (1867: 7). On the way, at “Ban- Ong-ta Krong” (1875: 128), about ten days before reaching his destination, Thomson had a “sharp attack of jungle fever” (1867: 7–8; 1875: 128). Were it not for his fellow-traveler, H.G. Kennedy from H.B.M. consular service, Thomson would “have met the fate of M. Mouhot, and perished in the jungle” (1867: 8). The precise dates of Thomson’s stay at Angkor or, in the words of Thomson, Nakhon, are not known. The same must be said about the duration of his stay: “several days” (1875: 150). On 31 January, he ar- rived at Paknam Kabin (1875: 124) and cannot have reached Angkor before March, since he “spent over a month in lumbering across the country” (1875: 128). Thomson must have left Angkor on 26 March at the latest, as on that day he “landed at Campong Luang” (1875: 155). -

This Newly Revamped Luxury Hotel Is the Best Reason to Visit Siem Reap

9/9/2020 Raffles Grand Hotel d’Angkor: The revamped luxury hotel is the best reason to visit Siem Reap this year | Fortune TRAVEL•HOTELS This newly revamped luxury hotel is the best reason to visit Siem Reap BY ALEXANDRA KIRKMAN July 1, 2020 7:00 AM EDT Most Popular SEARCH Want to understand why tech Congress likely to ax second Federal money for the $300 stocks are crashing? This round of stimulus checks, enhanced unemployment metric explains it all according to Goldman Sachs benefit is running out. Here’s forecast what to know Ed. note: This story was reported, written, and edited prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. “One of these temples…erected by some ancient Michelangelo might take an honorable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome.” So wrote the French explorer and naturalist Henri Mouhot of the staggering majesty of northern Cambodia’s Angkor—the world’s largest religious complex (at over 400 acres) and the seat of the Khmer kingdom from the ninth to 15th centuries. Having explored the ruins beginning in 1859, Mouhot is credited with alerting the West to Angkor’s existence, spurring a new wave of visitors and leading the French to play a pivotal role in its preservation. Yet guests of the Raffles Grand Hotel d’Angkor might never know of him if not for a characteristically exceptional amenity delivered to their rooms: a delicate chocolate bird’s nest—a nod to his avid interest in ornithology—accompanied https://fortune.com/2020/07/01/siem-reap-cambodia-raffles-hotel/ 1/12 9/9/2020 Raffles Grand Hotel d’Angkor: The revamped luxury hotel is the best reason to visit Siem Reap this year | Fortune by a magnifying glass, signifying his exacting attention to detail in his exquisite, photo-like sketches of the temples. -

In the Footsteps of Henri Mouhot

'A splendid night; the moon shines with extraordinary brilliancy, silvering the surface of this lovely river, bordered by high mountains, looking like a grand and gloomy rampart. The chirp of the crickets alone breaks the stillness.' Henri Mouhot sitting at the foot of a - Henri Mouhot wrote in his tree and drawing; Laos; wild elephants diary on the 15th of July 1861 while (background); servants preparing food (foreground) (Drawn by A. Poccourt sitting at the base of a tree in from a sketch by H. Mouhot) dense jungle on the bank of the mighty Mekong, near the ancient Laotian capital of Luang Prabang.1 In the footsteps of Henri Mouhot A French explorer in 19th Century Author's note: In 1997, I was so Thailand, Cambodia and Laos moved when I visited the site where Henri Mouhot was buried Dawn Rooney that on returning to Bangkok, I re-read his diaries. I was or nearly three years, from 1858 until his death in Laos in 1861, intrigued by this extraordinary Henri Mouhot explored the inner regions of Thailand (known human being, and felt compelled as Siam at that time), Cambodia and Laos. His legacy is a to reflect upon the little-known F detailed and unfinished diary of his keen observations of the places, man. people, animals, insects and shells of the region. Some of his notes are the earliest surviving records of previously uncharted areas. Alexandre Henri Mouhot was born on 15 May 1826, in the French village of Montbéliard, near the Swiss border. His father served in the administration of Louis Philippe and the Republic and his mother was a respected teacher who died when Henri was twenty years old. -

EARLY EXPLORERS the Impact of the French Presence in Cambodia

CHAPTER THREE: EARLY EXPLORERS The impact of the French presence in Cambodia during the first half of the French colonial project was not always deeply felt, particularly by much of the country’s rural population. However, beginning in the 1860s Cambodia had begun to enter into the consciousness of people in France. Although they had not had an extended history in the area in 1863 when the French signed the treaty that made Cambodia a French protectorate, French travelers had already visited and written about the territory, often in the form of travelers’ accounts in magazines and other periodicals. Nor was travel writing a new genre in 1863. The travel narrative had gained popularity in the eighteenth century as an adjunct to the Grand Tour. Travel diaries, guidebooks, autobiographies, and various other works of “heroic or mock-heroic”1 aspirations were all produced with growing popularity throughout the eighteenth century, and on through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, through to the present. It was during the early period of French colonization in Southeast Asia that the idea of distant places such as Cambodia, and eventually the idea of them as part of “Greater France,” began to form. The initial concept, and for many people in the métropole the only concept, of Cambodia came through the writing of explorers, scientists, and geographers. A major part of the formation of these ideas came through popular writing, such as travel journals, stories, and novels set in distant colonies. Many of these were serialized in publications like the Journal des Voyages, while others were compiled as book-length monographs. -

Family Vietnam, Cambodia & Laos

FAMILY VIETNAM, CAMBODIA & LAOS JUNE 29–JULY 14, 2018 This adventure of discovery and wonder starts in Saigon whose boomtown vibe is set against a backdrop of classic scenes and traditions. Explore the city’s grand boulevards, central squares, and river-front shops, but also get to know the people through such experiences as visiting the Truc Mai House where a local family of musical artists give an enchanting performance. Your next stop is Hanoi, widely considered one of Asia's most alluring and beautiful cities with its tree-lined avenues and French-colonial architecture. Chinese, Japanese, French, and American cultural influences can be seen in the city's collection of monuments and relic buildings, as well as its markets and its vibrant and fresh cuisine. Also visit Halong Bay, which is quintessential Vietnam with its karst outcroppings and traditional fishing villages, and where you can explore hidden beaches and waterways by kayak. The wonderful and sedate World Heritage town of Luang Prabang will delight you with its mountain- encircled setting on the Mekong River, the mix of gleaming temple roofs, crumbling French provincial architecture, and multi-ethnic population. Here you may enjoy an endearing visit with the revered Asian elephant. The program ends in Siem Reap, famous for the Temples of Angkor. Learn about how this impressively large area was lost to the jungle for so many years and what happened to its inhabitants. The efforts to restore and preserve what local artists and craftsman built so many hundreds of years ago is an archeological feat. With their grandeur of scale and an extraordinary delicacy in detail, the temples rank among peoples’ supreme artistic expressions. -

Introduction

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE DATE PERIOD MAJOR RULERS SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENTS 1900 Protectorate Norodom 1863 Treaty with French Ang Duong Phnom Penh the capital; Vietnamese control of Cambodia 1 1800 Vietnamese annex Delta 1700 Udong the capital 1600 Post-Classic Chai Chettha II Fall of Lovek to the Thai I N T R O D U C T I O N Ang Chan I 1500 1400 Court moves to Quatre Bras region Had the ancient Greeks and Romans known of Angkor, they surely would End of Khmer Empire; Thai invasions have counted that great city as the eighth wonder of the world. When the 1300 Jayavarman VIII Anti-Buddhist iconoclasm French naturalist and explorer Henri Mouhot – to whom was given the honour of first bringing its ruins to the general attention of Europe – entered 1200 Jayavarman VII Angkor Thom; apogee of Khmer Empire Tribhuvanadityavarman Angkor in 1860, he questioned the local people about its origin. Among Suryavarman II Cham invasion of Angkor 1100 Angkor Wat the explanations that they gave him was the suggestion that it might have Classic Udayadityavarman II Phimai been ‘the work of the giants’, leading Mouhot to exclaim: Suryavarman I Baphuon 1000 Rajendravarman II Banteay Srei The work of giants! The expression would be very just, if used 900 Jayavarman IV Yashodharapura the capital; Bakheng figuratively, in speaking of these prodigious works, of which no Hariharalaya the capital Indravarman I Founding of the Khmer Empire one who has not seen them can form any adequate idea; and in the 800 Jayavarman II construction of which patience, strength, and genius appear to have Jayadevi done their utmost in order to leave to future generations proofs of 700 Jayavarman I their power and civilization.1 Bhavavarman II 600 Chitrasena, Almost every early explorer (and virtually every other subsequent visitor) Bhavavarman I Ishanapura (Sambor Prei Kuk) Early Rudravarman has been wonder-struck by the beauty and multiplicity of the sculptures that 500 Kingdoms can be seen everywhere – on lintels and on walls, and free-standing before and within temples. -

White Lotus Co., Ltd

White Lotus Co., Ltd. GPo Box 1141, Bangkok 10501, thailand tel: (66) 0-38-239-883–4 Fax: (66) 0-38-239-885 internet: [email protected] Web-page: http://thailine.com/lotus office Address: 145/3-6 soi huay Yai Chin, huay Yai Pattaya, Banglamung, Chonburi 20150, thailand This catalogue lists only a small part of our stock. We carry the following Asian areas and subjects: New and out-of-print books and also old maps and prints (16th to 19th century): Burma, Vietnam, Yunnan, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia, China, India, Northeast India, Central Asia (defined as areas along the silk routes), Himalayas; Natural History: Flora and Fauna; Ecology; Performing Arts; Textiles; Religion, Philosophy and Belief Systems; Ceramics; Linguistics. Contents Burma ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Cambodia ......................................................................................................................................................6 Central Asia ..................................................................................................................................................7 Ceamics ........................................................................................................................................................7 Crafts ............................................................................................................................................................8