Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2013 Basingstoke Performance Order

Freshman – Sophomore Showcase Fall 2009 Basingstoke! A celebration of the operettas of William S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan Lyrics by William S. Gilbert (1836-1911) Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) With Guest Graduate Artists: Zachary Angus, Scott Gates, & Peter Morgan Music and Stage Director: Mark Crayton Associate Music Director and Piano: Giorgi Samadalashvili Stage Managers: Erin Stillson, Jeremy Cairns, Kiera Radvanski *** I have a song to sing, O (The Yeomen of the Guard) Elise Nathalie Young Jack Point Matthew Sund In sailing o’er life’s ocean wide (Ruddigore) Rose Ellen Jones Richard Nicholas Metzger Robin Zachary Angus Now wouldn’t you like to rule the roost (Princess Ida) Melissa Priscilla Ip Blanche Gabrielle Robles There is beauty in the bellow of the blast (The Mikado) Katisha Crystal Arrington Ko-Ko Peter Morgan Prithee pretty maiden (Patience) Patience Leah Taylor Grosvenor Michael Coduto If Saphir I choose to marry (Patience) Saphir Samantha D’Adamo Angela Alice Beals Duke Scott Gates Major Matthew Sund Colonel Peter Morgan None shall part us (Iolanthe) Phyllis Helen Knudsen Strephon Nicholas Metzger I am so proud (The Mikado) Pish-Tush Zachary Angus Ko-Ko Scott Gates Pooh-Bah Peter Morgan Intermission Three little maids from school are we (The Mikado) Yum-Yum Marissa Howard Peep-Bo Madison Marino Pitti-Sing Ally Perko So please you, Sir, we much regret (The Mikado) Yum-Yum Dana Brown Peep-Bo Priscilla Ip Pitti-Sing Felicia Warren Pooh-Bah Peter Morgan Ko-Ko Scott Gates (dialogue) O rapture, when alone together (The Gondoliers) Casilda Jamie Younger Luis Michael Coduto Here’s a how-de-do (The Mikado) Yum-Yum Priscilla Ip Nanki-Poo Michael Coduto Ko-Ko Zachary Angus In a contemplative fashion (The Gondoliers) Gianetta Rachel Jainks Tessa Ashley Lugo Marco Scott Gates Giuseppe Zachary Angus Finale: When a man has been a naughty baronette (Ruddigore) Rose Priscilla Ip Richard Nicholas Metzger Robin Peter Morgan Margaret Gabrielle Robles Sir Despard Michael Coduto Zorah Helen Knudsen Ensemble of Bridesmaids and Past Barronettes. -

ESO Highnotes November 2020

HighNotes is brought to you by the Evanston Symphony Orchestra for the senior members of our community who must of necessity isolate more because of COVID-!9. The current pandemic has also affected all of us here at the ESO, and we understand full well the frustration of not being able to visit with family and friends or sing in soul-renewing choirs or do simple, familiar things like choosing this apple instead of that one at the grocery store. We of course miss making music together, which is especially difficult because Musical Notes and Activities for Seniors this fall marks the ESO’s 75th anniversary – our Diamond Jubilee. While we had a fabulous season of programs planned, we haven’t from the Evanston Symphony Orchestra been able to perform in a live concert since February so have had to push the hold button on all live performances for the time being. th However, we’re making plans to celebrate our long, lively, award- Happy 75 Anniversary, ESO! 2 winning history in the spring. Until then, we’ll continue to bring you music and musical activities in these issues of HighNotes – or for Aaron Copland An American Voice 4 as long as the City of Evanston asks us to do so! O’Connor Appalachian Waltz 6 HighNotes always has articles on a specific musical theme plus a variety of puzzles and some really bad jokes and puns. For this issue we’re focusing on “Americana,” which seems appropriate for Gershwin Porgy and Bess 7 November, when we come together as a country to exercise our constitutional right and duty to vote for candidates of our choice Bernstein West Side Story 8 and then to gather with our family and friends for Thanksgiving and completely spoil a magnificent meal by arguing about politics… ☺ Tate Music of Native Americans 9 But no politics here, thank you! “Bygones” features things that were big in our childhoods, but have now all but disappeared. -

Single Page PDF.Indd

Hitting the streets for social change PAGE 23 MAKING A DIFFERENCE in the lives that follow Eugene “Gene” Morris (BSBA, ’69) (center) presents 2008-09 scholarship awards to Roosevelt seniors Joseph Celestin (left) and Heena Syed. At right, Robert Snyder (second from left) receives the “Top Prof” award from Morris, Lawrence Silverman and David Greene. ALLAN WEBER he late “Dr. Bob” Snyder was a great professor of the founding chairman of the Association of Black-Owned marketing and advertising at Roosevelt University Advertising Agencies. Additionally, he has received recog- who was an inspiration and a mentor to his students, nition for his work with many community and other profes- especially to me,” says Eugene “Gene” Morris (BSBA, ’69). sional organizations. When Morris heard Snyder was retiring and in ill-health, he Morris is proud of his successful career, but he gives established the Dr. Robert E. J. Snyder Endowed Scholarship much of the credit to Snyder, who practically “carried” in his honor. He also included Roosevelt University in his KLVUHOXFWDQWVWXGHQWWRWKHGRRUVWHSVRIKLVÀUVWDGYHUWLV estate plan. “I wanted to create a legacy for a beloved pro- ing agency. “He saw something in me that I didn’t see in fessor, give back to Roosevelt University — an institution myself. By endowing this scholarship in his name, I can pay that means so much to me — and help students. It was a win, tribute to him and help other students understand how one win, win decision,” says Morris. dedicated professor can have a lasting and dramatic impact With an advertising career that has spanned four decades, on their lives.” Morris knows a lot about winning … and success. -

75Thary 1935 - 2010

ANNIVERS75thARY 1935 - 2010 The Music & the Artists of the Bach Festival Society The Mission of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is to enrich the Central Florida community through presentation of exceptionally high-quality performances of the finest classical music in the repertoire, with special emphasis on oratorio and large choral works, world-class visiting artists, and the sacred and secular music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries in the High Baroque and Early Classical periods. This Mission shall be achieved through presentation of: • the Annual Bach Festival, • the Visiting Artists Series, and • the Choral Masterworks Series. In addition, the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. shall present a variety of educational and community outreach programs to encourage youth participation in music at all levels, to provide access to constituencies with special needs, and to participate with the community in celebrations or memorials at times of significant special occasions. Adopted by a Resolution of the Bach Festival Society Board of Trustees The Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is a private non-profit foundation as defined under Section 509(a)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code and is exempt from federal income taxes under IRC Section 501(c)(3). Gifts and contributions are deductible for federal income tax purposes as provided by law. A copy of the Bach Festival Society official registration (CH 1655) and financial information may be obtained from the Florida Division of Consumer Services by calling toll-free 1-800-435-7352 within the State. Registration does not imply endorsement, approval, or recommendation by the State. -

14) 244-3803 E-Mail: [email protected] Elizabeth Dworkin

Music in Concert with the Landscape There are music festivals and there are music festivals. Then there is the Moab Music Festival – a mélange of musical programming set in one of the most splendid landscapes on earth. Old and new music – chamber music, vocal music, jazz, traditional music – performed by outstanding musicians in a setting of form, color, and light that creates an unmatched artistic experience… Music in Concert with the Landscape. The Festival Founded in 1992 by Michael Barrett and Leslie Tomkins, prominent musicians based in New York, the Festival gathers world-class instrumentalists and vocalists annually to celebrate vibrant music in an awe-inspiring landscape. An ever- expanding audience comes from all parts of the United States and from Europe to enjoy this unique combination of sight and sound. Composers range from Bach to Bernstein, from Ravel to Rorem, from Dvorák to Danielpour. One performance may feature a vocalist celebrating a French chanteuse; the next a chamber ensemble performing Brahms; then a jazz ensemble playing with a Latin flair; then an exploration of contemporary music by the season’s Composer-in-Residence, who will be present to discuss his or her work. For patrons, the three weekend fall festival – which in 2003 won ASCAP’s coveted award for “Adventurous Programming” in the music festival category – is a potpourri of musical offerings performed by dynamic, highly accomplished musicians. In June, the Festival offers a four day “Musical Adventure” benefit raft trip with performances held at scenic sites along the Colorado River. Many concerts take advantage of the remarkable environment and are set outdoors in unique settings – under a pavilion along the Colorado River, in a tent under towering rock monoliths, in a park sheltered by the shade of an ancient cottonwood. -

Theater, Dance and Art Exhibits Flower in May

chicago business.co m http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20010428/ISSUE01/100016336/theater-dance-and-art-exhibits-flower-in-may Theater, dance and art exhibits flower in May By: Anne Spiselman April 30, 2001 Art ist ic ant le rs: This stag mad e o f fab ric, ste e l and le athe r is p art o f Art Chicag o 2001 at Navy Pie r. Pho to : Laura Fo rd From May Day to Memorial Day, the merriest month of f ers a multitude of openings and events. Theater: Chicago Shakespeare Theater (312/595-5600) kicks of f its new initiative, "The World's Stage," May 10 to June 2 with "The Tragedy of Hamlet," adapted and directed by Brit Peter Brook. The avant-garde production, f eaturing an ensemble of eight headed by Adrian Lester as the unhappy Dane, originated in Paris and is on a world tour that includes only three U.S. cities. Lookingglass Theatre Company (773/477-8088) teams with Evanston's Actors Gymnasium f or the gravity- def ying May 5-June 3 premiere of Charles Dickens' "Hard Times," the story of a f amily transf ormed by a circus perf ormer, adapted and directed by ensemble member Heidi Stillman and presented at the Ruth Page Center f or the Arts. Renowned actress Julie Harris returns to Victory Gardens Theater May 21 to June 17 to star with Ann Whitney in Claudia Allen's "Fossils," about two retired teachers who meet on vacation. Upstairs, Irish Repertory of Chicago continues its second season May 31 to June 24 with Marina Carr's "By the Bog of Cats," Euripides' "Medea" transplanted to the modern Irish midlands (773/871-3000 f or both). -

Underground Railroad: a Spiritual Journey View in Browser

Kathleen Battle – Underground Railroad: A Spiritual Journey View in browser 50 E Congress Pkwy Lily Oberman Chicago, IL 312.341.2331 (office) | 973.699.5312 (cell) AuditoriumTheatre.org [email protected] Release date: August 15, 2017 LEGENDARY SOPRANO KATHLEEN BATTLE MAKES HER AUDITORIUM THEATRE DEBUT WITH UNDERGROUND RAILROAD: A SPIRITUAL JOURNEY The Five-Time Grammy Winner Performs Spirituals with Top Chicago Choral and Gospel Singers Kathleen Battle – Underground Railroad: A Spiritual Journey | September 30, 2017 Legendary soprano Kathleen Battle makes her debut at the Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University, the Theatre for the People, on Saturday, September 30, with the program Underground Railroad: A Spiritual Journey. The five-time Grammy award winner and opera star breathes new life into this program of spirituals inspired by the Underground Railroad, the secret network that helped bring 19th-century slaves to freedom. Battle will be backed by a hand-picked group of top Chicago choir singers, led by Jonita Lattimore, an adjunct professor of voice at Roosevelt University's Chicago College of the Performing Arts. “Kathleen Battle is one of the most legendary opera singers of all time,” says Tania Castroverde Moskalenko, Auditorium Theatre CEO. “To have her perform this inspirational program at our historic theatre, accompanied by the most talented Chicago voices, will be a very special occasion.” The program includes songs like "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" and "Wade in the Water," as well as "I Been 'Buked" and "Lord, How Come Me Here." Battle performed a similar program when she made her triumphant return to the Metropolitan Opera in the fall of 2016 to rave reviews. -

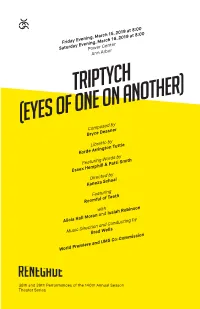

TRIPTYCH ) (EYES of ONE on ANOTHER Composed by Bryce Dessner

Friday Evening, March 15, 2019 at 8:00 Saturday Evening, March 16, 2019 at 8:00 Power Center Ann Arbor TRIPTYCH (EYES OF ONE ON ANOTHER) Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by Korde Arrington Tuttle Featuring Words by Essex Hemphill & Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran and Isaiah Robinson Music Direction and Conducting by Brad Wells World Premiere and UMS Co-Commission 38th and 39th Performances of the 140th Annual Season Theater Series This weekend’s performances are supported by Level X Talent. This weekend’s performances are funded in part by The Wallace Foundation. Produced in residency with and commissioned by University Musical Society, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. Co-produced by Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo Dudamel, music and artistic director. Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) was co-commissioned by BAM; Luminato Festival, Toronto, Canada; Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, Athens, Greece; Cincinnati Opera, Cincinnati, OH; Cal Performances, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, CA; Stanford Live, Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Adelaide Festival, Australia; John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts for performance as part of DirectCurrent 2019; ArtsEmerson: World on Stage, Emerson College, Boston, MA; Texas Performing Arts, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX; Holland Festival, Amsterdam; Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH; the Momentary, Bentonville, AR; Celebrity Series, Boston, MA; and developed in residency with MassMOCA, North Adams, MA. Media partnership provided by WEMU 89.1 FM, Between the Lines, and Metro Times. Special thanks to Chrisstina Hamilton and the Penny Stamps Distinguished Speaker Series, Joel Howell, Amanda Krugliak and the LSA Institute for the Humanities, and Richard Meyer for their participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. -

Composed by Ted Hearne Libretto by Mark Doten Directed by Daniel Fish

2014 NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, The Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Source Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Composed by Ted Hearne Libretto by Mark Doten Directed by Daniel Fish DATES: OCT 22—25 at 7:30pm LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 15min (no intermission) BAM 2014 Next Wave Festival Sponsor Bloomberg is the Season Sponsor Viacom is the BAM 2014 Music Sponsor Leadership support for music at BAM provided by: Frances Bermanzohn & Alan Roseman Pablo J. Salame #THESOURCE BAM Fisher 2014 NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL ENSEMBLE Nathan Koci Music Director The Conductor/Keyboard Courtney Orlando Violin Anne Lanzilotti Viola Leah Coloff Cello Source Taylor Levine Guitar Greg Chudzik Bass COMPOSER Ron Wiltrout Drums Ted Hearne PRODUCTION TEAM LIBRETTIST Sarah Peterson Production Manager Mark Doten Jason Kaiser Stage Manager Garth MacAleavey Sound Engineer DIRECTOR Gil Sperling Video Engineer Daniel Fish Philip White Vocal Processing Engineer PRODUCTION DESIGNER Jim Findlay PRODUCER BETH MORRISON PROJECTS VIDEO DESIGNERS Beth Morrison Creative Producer Jim Findlay & Daniel Fish Jecca Barry General Manager Noah Stern Weber Associate Producer LIGHTING DESIGER Kat Castle Production and Christopher Kuhl Administrative Intern COSTUME DESIGNER On Video: Terese Wadden Ernest Acosta, Dwayne Adams, Iones- cu-Ocnita Alexandra-Vasilia, Matthew ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Annenberg, Ed Bak, Hwa-Mi Barnett, Ashley Tata Rommel C. Barns, Rachel Bier, Judy Brick Freedman, Gregory Brown, WORLD PREMIERE Richard Francis Burst-Lazarus, Zorelly BAM 2014 NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL Cepeda, Doug Chapman, Thierry OCTOBER 22—25, 2014 Chauvaud, Christina Choe, Michael Christians, Janet D. -

ORDER YOUR TICKETS Today! 2014•2015 CALL 860-987-5900 CONCERT GUIDE HARTFORDSYMPHONY.Org

Hartford Symphony Orchestra 166 Capitol Avenue Hartford, CT 06106 ORDER YOUR TICKETS today! 2014•2015 CALL 860-987-5900 CONCERT GUIDE HARTFORDSYMPHONY.ORG Season Sponsor HSO programs are funded in part by COVER PHOTO OF Carolyn KUAN BY JANE SHAUCK PHOTOGRAPHY “A symphony must be like the world. It must contain everything.” - GUSTAV MAHLER music BRINGS US inside TOGETHER MAST ERWORKS 3 – 14 It connects musicians and audience POPS! 15 – 22 members, composers and students, SUNDAY 23 – 25 dancers and choirs, people and ideas. SERENADES GALA 26 FLEX CARDS 27 – 28 PERFORMANCES 29 – 30 AT A GLANCE Season Sponsor SEAN CHEN GUEST ARTIST The Masterworks series is a showcase of 2014 •2015 genius creativity – from Mozart, Beethoven and MASTERWORKS Brahms – to Gershwin, Copland and Bernstein. Plus, a season-long exploration of Gustav M ASTERWORKS CONCERTS are PERFORMED Mahler – and his passion, humanity and search THURS 7:30 PM | FRI & SAT 8 PM | SUN 3 PM AT THE BUSHNELL’S BELDING THEATER for metaphysical meaning in our lives. Tickets starting at $35 · $10 for Students Masterworks Series Sponsors inspire me 3 masterworks OPENING NIGHTS: BEETHOVEN’S PORGY AND BESS EMPEROR CONCERTO Oct OBER 16 – 19, 2014 NOE V MBER 13 – 16, 2014 Carolyn Kuan conductor Carolyn Kuan conductor Masayo Ishigure koto Martina Filjak piano Jonita Lattimore soprano Kevin Deas bass-baritone Brahms Tragic Overture, Op. 81 Hartford Chorale R. Strauss Death and Transfiguration, TrV 158, Op. 24 Richard Coffey, music director Beethoven Piano Concerto No.5 in E flat Major, First Cathedral Praises of Zion Choir Op. 73, “Emperor” James “J.J.” Hairston, director of music ministry Discover powerful themes of human existence. -

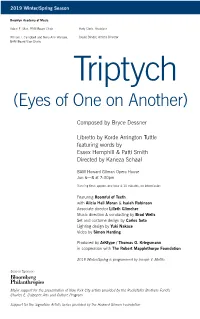

Triptych (Eyes of One on Another)

2019 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, BAM Board Chair Katy Clark, President William I. Campbell and Nora Ann Wallace, David Binder, Artistic Director BAM Board Vice Chairs Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by Korde Arrington Tuttle featuring words by Essex Hemphill & Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Jun 6—8 at 7:30pm Running time: approx. one hour & 10 minutes, no intermission Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran & Isaiah Robinson Associate director Lilleth Glimcher Music direction & conducting by Brad Wells Set and costume design by Carlos Soto Lighting design by Yuki Nakase Video by Simon Harding Produced by ArKtype / Thomas O. Kriegsmann in cooperation with The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 2019 Winter/Spring is programmed by Joseph V. Melillo. Season Sponsor: Major support for the presentation of New York City artists provided by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund’s Charles E. Culpeper Arts and Culture Program Support for the Signature Artists Series provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) Photo: Maria Baranova Contributing choreographer & performer Martell Ruffin Sound design by Damon Lange & Dylan Goodhue / nomadsound.net Production management William Knapp Dramaturgy by Talvin Wilks & Christopher Myers Managing producer ArKtype, J.J. El-Far Associate music director William Brittelle Associate lighting designer Valentina Migoulia Associate video designer Moe Shahrooz Production stage manager -

Challenge America

ALABAMA Magic City Smooth Jazz Birmingham, AL To support Jazz in the Park, a series of free concerts taking place at municipal neighborhood and state parks throughout Alabama.Intended to serve low income and rural underserved residents, the concert series will include performances by local and national jazz musicians. Studio Centreville, AL To support a music and dance performance series intended to serve economically disadvantaged residents.Related outreach activities will include master classes for underserved students, pre-concert discussions with guest artists, and educational film screenings about a diversity of artistic disciplines. Marshall County Retired Senior Volunteer Program, Incorporated Guntersville, AL To support Melodies and Musings - Our Appalachian Legacy, a three-day Southeast regional mountain dulcimer workshop, culminating in a public concert.The dulcimer performance and associated workshops will serve a low-income, rural population in Marshall County. ALASKA 49 Writers, Inc. Anchorage, AK To support a literary tour featuring author Melinda Moustakis, including workshops, readings, and related activities. Planned in partnership with “Alaska Quarterly Review” (AQR), a virtual book discussion of Moustakis’s book “Bear Down Bear North” will take place using the Alaska OWL (Online With Libraries) videoconferencing system. The virtual discussion will benefit remote, rural Alaska communities. The OWL sessions can be recorded and posted online, providing a long-term benefit for audiences. Live activities will also take place in Haines and Juneau, AK. Fairbanks Concert Association Fairbanks, AK To support performances by African Guitar Summit, a music ensemble featuring musicians from Guinea, Kenya, Burundi, Rwanda, and Madagascar.The project will include free outreach performances in the rural Alaskan communities of Healy, Delta Junction, and Fort Greely, as well as performances for K-12 students attending the Tri-Valley School.