Data Sheet For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductive Ecology of Heracleum Mantegazzianum

4 Reproductive Ecology of Heracleum mantegazzianum IRENA PERGLOVÁ,1 JAN PERGL1 AND PETR PYS˘EK1,2 1Institute of Botany of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Pru˚honice, Czech Republic; 2Charles University, Praha, Czech Republic Botanical creature stirs, seeking revenge (Genesis, 1971) Introduction Reproduction is the most important event in a plant’s life cycle (Crawley, 1997). This is especially true for monocarpic plants, which reproduce only once in their lifetime, as is the case of Heracleum mantegazzianum Sommier & Levier. This species reproduces only by seed; reproduction by vegetative means has never been observed. As in other Apiaceae, H. mantegazzianum has unspecialized flowers, which are promiscuously pollinated by unspecialized pollinators. Many small, closely spaced flowers with exposed nectar make each insect visitor to the inflorescence a potential and probable pollinator (Bell, 1971). A list of insect taxa sampled on H. mantegazzianum (Grace and Nelson, 1981) shows that Coleoptera, Diptera, Hemiptera and Hymenoptera are the most frequent visitors. Heracleum mantegazzianum has an andromonoecious sex habit, as has almost half of British Apiaceae (Lovett-Doust and Lovett-Doust, 1982); together with perfect (hermaphrodite) flowers, umbels bear a variable propor- tion of male (staminate) flowers. The species is considered to be self-compati- ble, which is a typical feature of Apiaceae (Bell, 1971), and protandrous (Grace and Nelson, 1981; Perglová et al., 2006). Protandry is a temporal sep- aration of male and female flowering phases, when stigmas become receptive after the dehiscence of anthers. It is common in umbellifers. Where dichogamy is known, 40% of umbellifers are usually protandrous, compared to only about 11% of all dicotyledons (Lovett-Doust and Lovett-Doust, 1982). -

B COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2019/2072 of 28 November 2019 Establishing Uniform Conditions for the Implementatio

02019R2072 — EN — 06.10.2020 — 002.001 — 1 This text is meant purely as a documentation tool and has no legal effect. The Union's institutions do not assume any liability for its contents. The authentic versions of the relevant acts, including their preambles, are those published in the Official Journal of the European Union and available in EUR-Lex. Those official texts are directly accessible through the links embedded in this document ►B COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2019/2072 of 28 November 2019 establishing uniform conditions for the implementation of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament and the Council, as regards protective measures against pests of plants, and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 690/2008 and amending Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/2019 (OJ L 319, 10.12.2019, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1199 of 13 August L 267 3 14.8.2020 2020 ►M2 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1292 of 15 L 302 20 16.9.2020 September 2020 02019R2072 — EN — 06.10.2020 — 002.001 — 2 ▼B COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2019/2072 of 28 November 2019 establishing uniform conditions for the implementation of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament and the Council, as regards protective measures against pests of plants, and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 690/2008 and amending Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/2019 Article 1 Subject matter This Regulation implements Regulation (EU) 2016/2031, as regards the listing of Union quarantine pests, protected zone quarantine pests and Union regulated non-quarantine pests, and the measures on plants, plant products and other objects to reduce the risks of those pests to an acceptable level. -

Impatiens Glandulifera (Himalayan Balsam) Chloroplast Genome Sequence As a Promising Target for Populations Studies

Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan balsam) chloroplast genome sequence as a promising target for populations studies Giovanni Cafa1, Riccardo Baroncelli2, Carol A. Ellison1 and Daisuke Kurose1 1 CABI Europe, Egham, Surrey, UK 2 University of Salamanca, Instituto Hispano-Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias (CIALE), Villamayor (Salamanca), Spain ABSTRACT Background: Himalayan balsam Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae) is a highly invasive annual species native of the Himalayas. Biocontrol of the plant using the rust fungus Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae is currently being implemented, but issues have arisen with matching UK weed genotypes with compatible strains of the pathogen. To support successful biocontrol, a better understanding of the host weed population, including potential sources of introductions, of Himalayan balsam is required. Methods: In this molecular study, two new complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of I. glandulifera were obtained with low coverage whole genome sequencing (genome skimming). A 125-year-old herbarium specimen (HB92) collected from the native range was sequenced and assembled and compared with a 2-year-old specimen from UK field plants (HB10). Results: The complete cp genomes were double-stranded molecules of 152,260 bp (HB92) and 152,203 bp (HB10) in length and showed 97 variable sites: 27 intragenic and 70 intergenic. The two genomes were aligned and mapped with two closely related genomes used as references. Genome skimming generates complete organellar genomes with limited technical and financial efforts and produces large datasets compared to multi-locus sequence typing. This study demonstrates the 26 July 2019 Submitted suitability of genome skimming for generating complete cp genomes of historic Accepted 12 February 2020 Published 24 March 2020 herbarium material. -

Clavibacter Michiganensis Subsp

Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin (2016) 46 (2), 202–225 ISSN 0250-8052. DOI: 10.1111/epp.12302 European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Organisation Europe´enne et Me´diterrane´enne pour la Protection des Plantes PM 7/42 (3) Diagnostics Diagnostic PM 7/42 (3) Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis Specific scope Specific approval and amendment This Standard describes a diagnostic protocol for Approved in 2004-09. Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis.1,2 Revision adopted in 2012-09. Second revision adopted in 2016-04. The diagnostic procedure for symptomatic plants (Fig. 1) 1. Introduction comprises isolation from infected tissue on non-selective Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis was origi- and/or semi-selective media, followed by identification of nally described in 1910 as the cause of bacterial canker of presumptive isolates including determination of pathogenic- tomato in North America. The pathogen is now present in ity. This procedure includes tests which have been validated all main areas of production of tomato and is quite widely (for which available validation data is presented with the distributed in the EPPO region (EPPO/CABI, 1998). Occur- description of the relevant test) and tests which are currently rence is usually erratic; epidemics can follow years of in use in some laboratories, but for which full validation data absence or limited appearance. is not yet available. Two different procedures for testing Tomato is the most important host, but in some cases tomato seed are presented (Fig. 2). In addition, a detection natural infections have also been recorded on Capsicum, protocol for screening for symptomless, latently infected aubergine (Solanum dulcamara) and several Solanum tomato plantlets is presented in Appendix 1, although this weeds (e.g. -

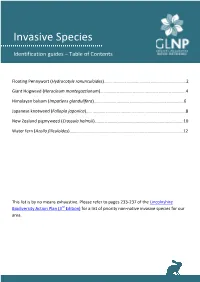

Invasive Species Identification Guide

Invasive Species Identification guides – Table of Contents Floating Pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides)……………………………….…………………………………2 Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)…………………………………………………………………….4 Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)………………………………………………………….…………….6 Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica)………………………………………………………………………………..8 New Zealand pigmyweed (Crassula helmsii)……………………………………………………………………….10 Water fern (Azolla filiculoides)……………………………………………………………………………………………12 This list is by no means exhaustive. Please refer to pages 233-237 of the Lincolnshire Biodiversity Action Plan (3rd Edition) for a list of priority non-native invasive species for our area. Floating pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Invasive species identification guide Where is it found? Floating on the surface or emerging from still or slowly moving freshwater. Can be free floating or rooted. Similar to…… Marsh pennywort (see bottom left photo) – this has a smaller more rounded leaf that attaches to the stem in the centre rather than between two lobes. Will always be rooted and never free floating. Key features Lobed leaves Fleshy green or red stems Floating or rooted Forms dense interwoven mats Leaf Leaves can be up to 7cm in diameter. Lobed leaves can float on or stand above the water. Marsh pennywort Roots Up to 5cm Fine white Stem attaches in roots centre More rounded leaf Floating pennywort Larger lobed leaf Stem attaches between lobes Photos © GBNNSS Workstream title goes here Invasive species ID guide: Floating pennywort Management Floating pennywort is extremely difficult to control due to rapid growth rates (up to 20cm from the bank each day). Chemical control: Can use glyphosphate but plant does not rot down very quickly after treatment so vegetation should be removed after two to three weeks in flood risk areas. Regular treatment necessary throughout the growing season. -

Implementation of Recommendations on Invasive Alien Species / Mise En Œuvre Des Recommandations Sur Les Espèces Exotiques Envahissantes

Strasbourg, 13 May 2011 T-PVS/Inf (2011) 3 [Inf03a_2011.doc] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Bern Convention Group of Experts on Invasive Alien Species / Groupe d’experts de la Convention de Berne sur les espèces exotiques envahissantes St. Julians, Malta (18-20 May 2011) / St Julians, Malte (18-20 mai 2011) __________ Implementation of recommendations on Invasive Alien Species / Mise en œuvre des recommandations sur les espèces exotiques envahissantes National reports and contributions / Rapports nationaux et Contributions-- Document prepared by the Directorate of Culture and of Cultural and Natural Heritage This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/Inf (2011) 3 - 2 - CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE __________ 1. Armenia / Arménie ................................................................................................................ 3 2. Belgium / Belgique ................................................................................................................ 7 3. France / France....................................................................................................................... 16 4. Ireland / Irlande...................................................................................................................... ²19 5. Italy / Italie............................................................................................................................ -

048 (3) Plenodomus Tracheiphilus (Formerly Phoma Tracheiphila)

Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin (2015) 45 (2), 183–192 ISSN 0250-8052. DOI: 10.1111/epp.12218 European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Organisation Europe´enne et Me´diterrane´enne pour la Protection des Plantes PM 7/048 (3) Diagnostics Diagnostic PM 7/048 (3) Plenodomus tracheiphilus (formerly Phoma tracheiphila) Specific scope Specific approval and amendment This Standard describes a diagnostic protocol for First approved in 2004–09. Plenodomus tracheiphilus (formerly Phoma tracheiphila).1 Revision approved in 2007–09 and 2015–04. Phytosanitary categorization: EPPO A2 list N°287; EU 1. Introduction Annex designation II/A2. Plenodomus tracheiphilus is a mitosporic fungus causing a destructive vascular disease of citrus named ‘mal secco’. 3. Detection The name of the disease was taken from the Italian words ‘male’ = disease and ‘secco’ = dry. The disease first 3.1 Symptoms appeared on the island of Chios in Greece in 1889, but the causal organism was not determined until 1929. Symptoms appear in spring as leaf and shoot chlorosis fol- The principal host species is lemon (Citrus limon), but lowed by a dieback of twigs and branches (Fig. 2A). On the the fungus has also been reported on many other citrus spe- affected twigs, immersed, flask-shaped or globose pycnidia cies, including those in the genera Citrus, Fortunella, appear as black points within lead-grey or ash-grey areas Poncirus and Severina; and on their interspecific and (Fig. 3B). On fruits, browning of vascular bundles can be intergenic hybrids (EPPO/CABI, 1997 – Migheli et al., observed in the area of insertion of the peduncle. 2009). -

Data Sheet on Heracleum Mantegazzianum, H. Sosnowskyi

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Organisation Europe´enne et Me´diterrane´enne pour la Protection des Plantes EPPO data sheet on Invasive Alien Plants Fiches informatives sur les plantes exotiques envahissantes Heracleum mantegazzianum, Heracleum sosnowskyi and Heracleum persicum ‘synonyms’). Other historical synonyms include Heracleum aspe- Identity of Heracleum mantegazzianum rum Marschall von Bieberstein, Heracleum caucasicum Steven, Scientific name: Heracleum mantegazzianum Sommier & Heracleum lehmannianum Bunge, Heracleum panaces Steven, Levier Heracleum stevenii Mandenova, Heracleum tauricum Steven and Synonyms: Heracleum circassicum Mandenova, Heracleum Heracleum villosum Sprengel. The names of two other species grossheimii Mandenova, Heracleum giganteum Hornemann. now naturalized in Europe (Heracleum persicum Fischer and Taxonomic position: Apiaceae. H. sosnowskyi Mandenova) are also historical synonyms of Common names: giant hogweed, giant cow parsnip, cartwheel H. mantegazzianum. The name Heracleum trachyloma Fischer & flower (English), kæmpe-bjørneklo (Danish), berce du caucase, C.A. Meyer has recently been used for the most widespread Her- berce de Mantegazzi (French), Herkulesstaude, Riesenba¨renklau, acleum sp. naturalized in the UK (Sell & Murrell, 2009). kaukasischer Ba¨renklau (German), kaukasianja¨ttiputki (Finnish), Phytosanitary categorization: EPPO List of invasive alien plants. kjempebjønnkjeks (Norwegian), barszcz mantegazyjski (Polish), kaukasisk ja¨ttefloka (Swedish), hiid-karuputk (Estonian), -

Maine Coefficient of Conservatism

Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity Conservatism Wetness Abies balsamea balsam fir native 3 0 Abies concolor white fir non‐native 0 Abutilon theophrasti velvetleaf non‐native 0 3 Acalypha rhomboidea common threeseed mercury native 2 3 Acer ginnala Amur maple non‐native 0 Acer negundo boxelder non‐native 0 0 Acer pensylvanicum striped maple native 5 3 Acer platanoides Norway maple non‐native 0 5 Acer pseudoplatanus sycamore maple non‐native 0 Acer rubrum red maple native 2 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple native 6 ‐3 Acer saccharum sugar maple native 5 3 Acer spicatum mountain maple native 6 3 Acer x freemanii red maple x silver maple native 2 0 Achillea millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. borealis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea ptarmica sneezeweed non‐native 0 3 Acinos arvensis basil thyme non‐native 0 Aconitum napellus Venus' chariot non‐native 0 Acorus americanus sweetflag native 6 ‐5 Acorus calamus calamus native 6 ‐5 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry native 7 5 Actaea racemosa black baneberry non‐native 0 Actaea rubra red baneberry native 7 3 Actinidia arguta tara vine non‐native 0 Adiantum aleuticum Aleutian maidenhair native 9 3 Adiantum pedatum northern maidenhair native 8 3 Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine native 7 Aegopodium podagraria bishop's goutweed non‐native 0 0 Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity -

Impatiens Glandulifera

NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet Impatiens glandulifera Author of this fact sheet: Harry Helmisaari, SYKE (Finnish Environment Institute), P.O. Box 140, FIN-00251 Helsinki, Finland, Phone + 358 20 490 2748, E-mail: [email protected] Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet: Helmisaari, H. (2010): NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – Impatiens glandulifera. – From: Online Database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species – NOBANIS www.nobanis.org, Date of access x/x/201x. Species description Scientific name: Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae). Synonyms: Impatiens roylei Walpers. Common names: Himalayan balsam, Indian balsam, Policeman's Helmet (GB), Drüsiges Springkraut, Indisches Springkraut (DE), kæmpe-balsamin (DK), verev lemmalts (EE), jättipalsami (FI), risalísa (IS), bitinė sprigė (LT), puķu sprigane (LV), Reuzenbalsemien (NL), kjempespringfrø (NO), Niecierpek gruczolowaty, Niecierpek himalajski (PL), недотрога железконосная (RU), jättebalsamin (SE). Fig. 1 and 2. Impatiens glandulifera in an Alnus stand in Helsinki, Finland, and close-up of the seed capsules, photos by Terhi Ryttäri and Harry Helmisaari. Fig. 3 and 4. White and red flowers of Impatiens glandulifera, photos by Harry Helmisaari. Species identification Impatiens glandulifera is a tall annual with a smooth, usually hollow and jointed stem, which is easily broken (figs. 1-4). The stem can reach a height of 3 m and its diameter can be up to several centimetres. The leaves are opposite or in whorls of 3, glabrous, lanceolate to elliptical, 5-18 cm long and 2.5-7 cm wide. The inflorescences are racemes of 2-14 flowers that are 25-40 mm long. Flowers are zygomorphic, their lowest sepal forming a sac that ends in a straight spur. -

Inf26erev 2011 Code of Conduct Zoos+Aquaria IAS FINAL

Strasbourg, 8 October 2012 T-PVS/Inf (2011) 26 revised [Inf26erev_2011.doc] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee 32nd meeting Strasbourg, 27-30 November 2012 __________ EUROPEAN CODE OF CONDUCT ON ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS AND AQUARIA AND INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES Code, rationale and supporting information - FINAL VERSION – (October 2012) Report prepared by Mr Riccardo Scalera, Mr Piero Genovesi, Mr Danny de man, Mr Bjarne Klausen, Ms Lesley Dickie This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/Inf (2011) 26 rev. - 2 – INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................3 1.1 Why a Code of Conduct ? ......................................................................................................4 2. SCOPE AND AIM ..........................................................................................................................6 3. BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................7 3.1 The History of Zoological Gardens and Aquaria.....................................................................7 3.2 Zoological Gardens and Aquaria as pathways for IAS............................................................7 3.2.1 IAS originating from zoological gardens and aquaria ....................................................8 -

Data Requirements for the Authorisation of a New

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes 14/19647 Examples of zonal efficacy evaluation Clarification of efficacy data requirements for the authorization of an insecticide against aphids, thrips and whiteflies in ornamental plants in greenhouses in the EU Proposed by Claudia Jilesen, National Plant Protection Organization, the Netherlands, February 2014 This document is intended to assist applicants and evaluators to interpret EPPO Standard PP 1/278 Principles of zonal data production and evaluation. Expert judgement should be applied in all cases. The focus of this paper is in particular on the number and location of trials for the justification of effectiveness, phytotoxicity and resistance issues. There is a need to provide clarification of these areas as part of the zonal authorization process for plant protection products (as defined in EU Regulation 1107/2009 (EC, 2009). Regulation EC 1107/2009 specifies that the assessment of plant protection products should be conducted on a zonal basis. Article 33 of EC 1107/2009 considers that in the case of an application for use in greenhouses, only one Member State evaluates the application, taking account of all zones. All trials should be carried out under Good Experimental Practice (GEP) and using all relevant general EPPO Standards. Efficacy trials should be performed according to relevant EPPO Standards PP 1/23 Aphids on ornamental plants, PP 1/160 Thrips on glasshouse crops and 1/36 Whiteflies (Trialeurodes vaporariorum, Bemisia tabaci) on protected crops (available at http://pp1.eppo.int/). The most common and harmful sucking insects in ornamental plants are aphids, thrips and whiteflies and this example applies only to them.