Music And/As Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

AMRC Journal Volume 21

American Music Research Center Jo urnal Volume 21 • 2012 Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder The American Music Research Center Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Dominic Ray, O. P. (1913 –1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music Eric Hansen, Editorial Assistant Editorial Board C. F. Alan Cass Portia Maultsby Susan Cook Tom C. Owens Robert Fink Katherine Preston William Kearns Laurie Sampsel Karl Kroeger Ann Sears Paul Laird Jessica Sternfeld Victoria Lindsay Levine Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Kip Lornell Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25 per issue ($28 outside the U.S. and Canada) Please address all inquiries to Eric Hansen, AMRC, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. Email: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISBN 1058-3572 © 2012 by Board of Regents of the University of Colorado Information for Authors The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing arti - cles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and proposals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (exclud - ing notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, Uni ver - sity of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. Each separate article should be submitted in two double-spaced, single-sided hard copies. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

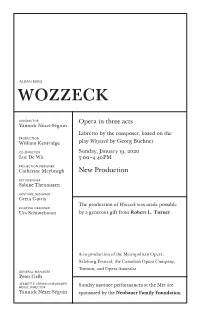

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

How Does the Brain Process Music?

I MEDICINE, MUSIC AND THE MIND How does the brain process music? Jason Warren Jason D Warren ABSTRACT – The organisation of the musical rhythm, metre) and the distinctive instrumental or PhD FRACP, brain is a major focus of interest in contemporary human voices (‘tone quality’ or timbre) that carries Honorary neuroscience. This reflects the increasing sophis- the tune. It is not obvious a priori how these dimen- Consultant tication of tools (especially imaging techniques) sions might translate to brain organisation, though it Neurologist, to examine brain anatomy and function in health would seem unlikely that a single ‘music centre’ National Hospital and disease, and the recognition that music processes them all. for Neurology and provides unique insights into a number of aspects The problems this entails are not unlike those con- Neurosurgery, of nonverbal brain function. The emerging picture fronting the study of that other uniquely human, Queen Square, is complex but coherent, and moves beyond London multidimensional capacity, language. Like language, older ideas of music as the province of a single music is an abstract, rule-based system (arguably the Clin Med brain area or hemisphere to the concept of music only one of comparable complexity), and the 2008;8:32–36 as a ‘whole-brain’ phenomenon. Music engages a parallels between music and language are seductive. distributed set of cortical modules that process It is possible to devise musical analogies for linguistic different perceptual, cognitive and emotional elements such as ‘vocabulary’ and ‘grammar’, and components with varying selectivity. ‘Why’ rather at a clinical level, to find musical equivalents for the than ‘how’ the brain processes music is a key aphasias. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

61 CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS and CONFLICT with STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations a Close Friendship Between Arthur Lourié A

CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS AND CONFLICT WITH STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations A close friendship between Arthur Lourié and Igor Stravinsky began once both had left their native Russian homeland and settled on French soil. Stravinsky left before the Russian Revolution occurred and was on friendly terms with his countrymen when he departed; from the premiere of the Firebird (1910) in Paris onward he was the favored representative of Russia abroad. "The force of his example bequeathed a russkiv slog (Russian manner of expression or writing) to the whole world of twentieth-century concert music."1 Lourié on the other hand defected in 1922 after the Bolshevik Revolution and, because he had abandoned his position as the first commissar of music, he was thereafter regarded as a traitor. Fortunately this disrepute did not follow him to Paris, where Stravinsky, as did others, appreciated his musical and literary talents. The first contact between the two composers was apparently a correspondence from Stravinsky to Lourié September 9, 1920 in regard to the emigration of Stravinsky's mother. The letter from Stravinsky thanks Lourié for previous help and requests further assistance in selling items from Stravinsky's 1 Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the 61 62 apartment in order to raise money for his mother's voyage to France.2 She finally left in 1922, which was the year in which Lourié himself defected while on government business in Berlin. The two may have met for the first time in 1923 when Stravinsky's Histoire du Soldat was performed at the Bauhaus exhibit in Weimar, Germany. -

American Mavericks Festival

VISIONARIES PIONEERS ICONOCLASTS A LOOK AT 20TH-CENTURY MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES, FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY EDITED BY SUSAN KEY AND LARRY ROTHE PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF CaLIFORNIA PRESS The San Francisco Symphony TO PHYLLIS WAttIs— San Francisco, California FRIEND OF THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, CHAMPION OF NEW AND UNUSUAL MUSIC, All inquiries about the sales and distribution of this volume should be directed to the University of California Press. BENEFACTOR OF THE AMERICAN MAVERICKS FESTIVAL, FREE SPIRIT, CATALYST, AND MUSE. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England ©2001 by The San Francisco Symphony ISBN 0-520-23304-2 (cloth) Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI / NISO Z390.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Printed in Canada Designed by i4 Design, Sausalito, California Back cover: Detail from score of Earle Brown’s Cross Sections and Color Fields. 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 v Contents vii From the Editors When Michael Tilson Thomas announced that he intended to devote three weeks in June 2000 to a survey of some of the 20th century’s most radical American composers, those of us associated with the San Francisco Symphony held our breaths. The Symphony has never apologized for its commitment to new music, but American orchestras have to deal with economic realities. For the San Francisco Symphony, as for its siblings across the country, the guiding principle of programming has always been balance. -

Dossier Pédagogique the Rake's Progress

Dossier pédagogique Opéra / Nouvelle production THE RAKE’S PROGRESS DE IGOR STRAVINSKI DIRECTION MUSICALE ARIE VAN BEEK MISE EN SCÈNE DAVID LESCOT AVEC L’ORCHESTRE DE PICARDIE ET LE CHŒUR DE L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Sa 8, Ma 11, Je 13, Di 16 (16h), Me 19 OCTOBRE 2011 à 20h Contacts Service des relations avec les publics [email protected] Dossier réalisé avec la collaboration de Sébastien Bouvier, enseignant missionné à l’Opéra de Lille Septembre 2011 Sommaire Préparer votre venue à l’Opéra 3 THE RAKE’S PROGRESS Résumé 4 Synopsis 5 Igor Stravinski 6 La genèse de l’œuvre 7 Guide d’écoute 11 Vocabulaire 31 Pistes pédagogiques 33 Références 34 THE RAKE’S PROGRESS À L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Distribution 35 Mise en scène, note d’intention 36 Entretien avec Arie van Beek, directeur musical 38 Repères biographiques 40 POUR ALLER PLUS LOIN La voix à l’opéra 41 Qui fait quoi à l’opéra ? 42 L’Opéra de Lille, un lieu, une histoire 43 ANNEXE Fiche instruments 47 2 Préparer votre venue Ce dossier vous aidera à préparer votre venue avec les élèves. L’équipe de l’Opéra de Lille est à votre disposition pour toute information complémentaire et pour vous aider dans votre approche pédagogique. Si le temps vous manque, nous vous conseillons, prioritairement, de : - lire la fiche résumé et le synopsis détaillé - faire une écoute des extraits représentatifs de l’opéra (guide d’écoute) Recommandations Le spectacle débute à l’heure précise. Il est donc impératif d’arriver au moins 30 minutes à l’avance, les portes sont fermées dès le début du spectacle. -

Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 12:06 Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon Volume 26, numéro 1, 2005 Résumé de l'article Le processus compositionnel de Stravinsky durant sa période néo-classique est URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013243ar ici mis en relief et étudié par le biais des esquisses, brouillons et autres copies DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar manuscrites de la Piano-Rag-Music. Ces autographes révèlent le matériel initial du compositeur, ses méthodes de travail, l’ampleur de ses préoccupations Aller au sommaire du numéro compositionnelles et les conditions étonnantes d’assemblage de l’œuvre. D’ailleurs, elles confirment que la fusion entre les trois éléments distincts opérée dans le titre de l’ouvrage par le trait d’union définit à la fois le contenu Éditeur(s) de l’œuvre et son objectif. La virtuosité pianistique et la vitalité rythmique de l’improvisation de type ragtime sont synthétisés en une forme musicale pure Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités qui est ni conventionnelle ni hybride, mais plutôt une résultante du matériel canadiennes en soi. ISSN 1911-0146 (imprimé) 1918-512X (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Gordon, T. (2005). Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music. Intersections, 26(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar Copyright © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des universités canadiennes, 2006 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

MTO 7.2: Cook, Between Process and Product

Volume 7, Number 2, April 2001 Copyright © 2001 Society for Music Theory Nicholas Cook KEYWORDS: performance theory, work, text, script, analysis ABSTRACT: The text-based orientation of traditional musicology and theory hampers thinking about music as a performance art. Music can be understood as both process and product, but it is the relationship between the two that defines “performance” in the Western “art” tradition. Drawing on interdisciplinary performance theory (particularly theatre studies, poetry reading, and ethnomusicology), I set out issues and outline approaches for the study of music as performance; by thinking of scores as “scripts” rather than “texts,” I argue, we can understand performance as a generator of social meaning. Received 22 January 2001 The Idol Overturned [1] “The performer,” Schoenberg is supposed to have said, “for all his intolerable arrogance, is totally unnecessary except as his interpretations make the music understandable to an audience unfortunate enough not to be able to read it in print.”(1) It’s difficult to know quite how seriously to take such a statement, or Leonard Bernstein’s injunction (Bernstein, of all people!) that the conductor “be humble before the composer; that he never interpose himself between the music and the audience; that all his efforts, however strenuous or glamorous, be made in the service of the composer’s meaning.”(2) And it might be tempting to blame it all on Stravinsky, who somehow elevated a fashionable anti-Romantic stance of the 1920s into a permanent and apparently self-evident philosophy of music, according to which “The secret of perfection lies above all in [the performer’s] consciousness of the law imposed on him by the work he is performing,” so that music should be not interpreted but merely executed.(3) Or if not on Stravinsky, then on the rise of the recording industry, which has created a performance style designed for infinite iterability, resulting over the course of the twentieth century in a “general change of emphasis .