Frank Ramsey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographical Sketches of Key Pupils

Appendix E Biographical Sketches of Key Pupils John Godolphin Bennett (1897–1974) was a scientist and philosopher who first met Gurdjieff in Istanbul in 1921 when he was working as an interpreter and personal intel- ligence officer in the British Army. In London that year Bennett began attending meet- ings held by Ouspensky on Gurdjieff’s teaching, and in 1922 he met Gurdjieff again. Bennett made brief visits to Gurdjieff’s Institute at Fontainebleau in February and August of 1923. In the 1930s Bennett formed his own group of followers, and rejoined Ouspensky’s group. In 1946 Bennett established an Institute at Coombe Springs, Kingston-on-Thames in Surrey. After a twenty-five year break Bennett renewed his ties with Gurdjieff in Paris in 1948 and 1949, at which time Gurdjieff taught him his new Movements. In 1949 Gurdjieff named Bennett his ‘official representative’ in England, with reference to the publication of Tales. After Gurdjieff’s death Bennett became an independent teacher, drawing from Sufi, Indian, Turkish, and Subud traditions. In 1953 he travelled through the Middle East hoping to locate the sources of Gurdjieff’s teach- ing among Sufi masters. By the end of his life he had written around thirty-five books related to Gurdjieff’s teaching.1 Maurice Nicoll (1884–1953) studied science at the University of Cambridge before travelling through Vienna, Berlin, and Zurich, eventually to become an eminent psy- chiatrist and colleague of Carl Gustav Jung. Nicoll was a member of the Psychosynthesis group, which met regularly under A.R. Orage, and this connection led Nicoll to Ouspensky in London in 1921. -

Dissemination of the Work During Gurdjieff’S Lifetime

DISSEMINATION OF THE WORK DURING GURDJIEFF’S LIFETIME Throughout the course of his teaching Gurdjieff employed deputies or “helper- instructors” to assist with disseminating his ideas. During the Russian phase of the teaching, P.D. Ouspensky and other senior students would often give introductory lectures to newcomers as preparation for Gurdjieff’s presentation of more advanced material. A.R. Orage was responsible for introducing Work ideas to Gurdjieff’s New York groups in the 1920s. Under Gurdjieff’s direction Jeanne de Salzmann organized and led French groups during the 1930s and was largely responsible for teaching Gurdjieff’s sacred dances. Gurdjieff realized that if his teaching was to take root in the West he needed to train and teach students with a Western background who could assist him in making the teach- ing culturally appropriate. Gurdjieff’s efforts to train his assistants may also have come from a desire to develop them into independent teachers in their own right. During a period of physical incapacity following his serious automobile accident in July 1924, Gurdjieff’s Institute at the Prieuré in Fontainebleau virtually ground to a halt. It was then that Gurdjieff realized that none of his students possessed the degree of inner development or the leadership capacity to carry his work forward in his absence: He had to acknowledge what for him was a devastating realization: that the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man had failed insofar as not a single pupil, nor even all of his students collectively, possessed the inner resources required even temporarily to sustain the momentum of life he had set into motion. -

Rudolf Ekstein Collection of Material About Sigmund Freud, the Freuds, and the Freudians Biomed.0452

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c89g5v0c No online items Finding Aid for the Rudolf Ekstein Collection of Material about Sigmund Freud, the Freuds, and the Freudians Biomed.0452 Finding aid prepared by Courtney Dean, 2020. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2020 November 25. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Rudolf Ekstein Biomed.0452 1 Collection of Material about Sigmund Freud, the Freuds,... Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Rudolf Ekstein collection of material about Sigmund Freud, the Freuds, and the Freudians Source: Tiano, Jean Ekstein Creator: Ekstein, Rudolf Identifier/Call Number: Biomed.0452 Physical Description: 6.4 Linear Feet(1 box, 6 cartons) Date (inclusive): circa 1856-1995 Language of Material: Materials are in English and German. Conditions Governing Access Unprocessed collection. Material is unavailable for access. Please contact Special Collections reference ([email protected]) for more information. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical objects belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. All other rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Immediate Source of Acquisition Gift of Jean Ekstein Tiano and Herman Tiano, 4 December 2014. Processing Information Collections are processed to a variety of levels depending on the work necessary to make them usable, their perceived user interest and research value, availability of staff and resources, and competing priorities. -

A Brief History of the British Psychoanalytical Society

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BRITISH PSYCHOANALYTICAL SOCIETY Ken Robinson When Ernest Jones set about establishing psychoanalysis in Britain, two intertwining tasks faced him: establishing the reputation of psychoanalysis as a respectable pursuit and defining an identity for it as a discipline that was distinct from but related to cognate disciplines. This latter concern with identity would remain central to the development of the British Society for decades to come, though its inflection would shift as the Society sought first to mark out British psychoanalysis as having its own character within the International Psychoanalytical Association, and then to find a way of holding together warring identities within the Society. Establishing Psychoanalysis: The London Society Ernest Jones’ diary for 1913 contains the simple entry for October 30: “Ψα meeting. Psycho-med. dinner” (Archives of the British Psychoanalytical Society, hereafter Archives). This was the first meeting of the London Psychoanalytical Society. In early August Jones had returned to London from ignominious exile in Canada after damaging accusations of inappropriate sexual conduct in relation to children. Having spent time in London and Europe the previous year, he now returned permanently, via Budapest where from June he had received analysis from Ferenczi. Once in London he wasted no time in beginning practice as a psychoanalyst, seeing his first patient on the 14th August (Diary 1913, Archives), though he would soon take a brief break to participate in what would turn out to be a troublesome Munich Congress in September (for Jones’s biography generally, see Maddox [2006]). Jones came back to a London that showed a growing interest in unconscious phenomena and abnormal psychology. -

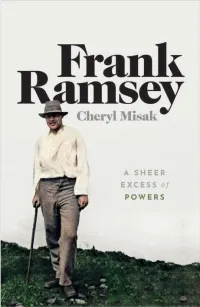

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, Orage

Black Sheep Philosophers by Gorham Munson On October 29, 1949, at the American Hospital in Paris died a Caucasian Greek named Georgy Ivanovitch Gurdjieff. A few nights later at Cooper Union, New York, a medal was presented to the revolutionary architect Frank Lloyd Wright. After his part in the ceremony was over, Wright asked the chairman's permission to make are announcement. "The greatest man in the world," he said, "has recently died. His name was Gurdjieff." Few, if any, in Wright's audience had ever heard the name before, which is quite understandable: Gurdjieff avoided reporters and managed most of the time to keep out of the media publicity. However, there was one kind of publicity that he always got in Europe and America, and that was the kind made by the wagging human tongue: gossip. In 1921 he showed up in Constantinople. "His coming to Constantinople," says the British scientist, J.G. Bennett, "was heralded by the usual gossip of the bazaars. Gurdjieff was said to be a great traveler and a linguist who knew all the Oriental languages, reputed by the Moslems to be a convert to Islam, and by the Christians to be a member of some obscure Nestorian sect." In those days Bennett, who is now an expert on coal utilization, was in charge of a British Intelligence section working in Constantinople. He met Gurdjieff and found him neither Moslem nor Christian. Bennett reported that "his linguistic attainments stopped short near the Caspian Sea, so that we could converse only with difficulty in a mixture of Azerbaidjan Tartar and Osmanli Turkish. -

Unpublished Letters of Ezra Pound to James, Nora, and Stanislaus Joyce Robert Spoo

University of Tulsa College of Law TU Law Digital Commons Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works 1995 Unpublished Letters of Ezra Pound to James, Nora, and Stanislaus Joyce Robert Spoo Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/fac_pub Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 32 James Joyce Q. 533-81 (1995). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unpublished Letters of Ezra Pound to James, Nora, and Stanislaus Joyce Robert Spoo University of Tulsa According to my computation, 198 letters between Ezra so come Pound and James Joyce have far to light. Excluding or letters to by family members (as when Joyce had Nora write for him during his iUnesses), I count 103 letters by Joyce to Pound, 26 of which have been pubUshed, and 95 letters by Pound to Joyce, 75 of which have been published. These numbers should give some idea of the service that Forrest Read performed nearly thirty years ago in collecting and pubUshing the letters of Pound to Joyce,1 and make vividly clear also how poorly represented in print Joyce's side of the correspondence is. Given the present policy of the Estate of James Joyce, we cannot expect to see this imbalance rectified any time soon, but Iwould remind readers that the bulk of Joyce's un pubUshed letters to Pound may be examined at Yale University's Beinecke Library. -

FREUD and the PROBLEM with MUSIC: a HISTORY of LISTENING at the MOMENT of PSYCHOANALYSIS a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty

FREUD AND THE PROBLEM WITH MUSIC: A HISTORY OF LISTENING AT THE MOMENT OF PSYCHOANALYSIS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michelle R. Duncan May 2013 © 2013 Michelle R. Duncan FREUD AND THE PROBLEM OF MUSIC: A HISTORY OF LISTENING AT THE MOMENT OF PSYCHOANALYSIS Michelle R. Duncan, Ph. D. Cornell University 2013 An analysis of voice in performance and literary theory reveals a paradox: while voice is generally thought of as the vehicle through which one expresses individual subjectivity, in theoretical discourse it operates as a placeholder for superimposed content, a storage container for acquired material that can render the subjective voice silent and ineffectual. In grammatical terms, voice expresses the desire or anxiety of the third rather than first person, and as such can be constitutive of both identity and alterity. In historical discourse, music operates similarly, absorbing and expressing cultural excess. One historical instance of this paradox can be seen in the case of Sigmund Freud, whose infamous trouble with music has less to do with aesthetic properties of the musical art form than with cultural anxieties surrounding him, in which music becomes a trope for differences feared to potentially “haunt” the public sphere. As a cultural trope, music gets mixed up in a highly charged dialectic between theatricality and anti-theatricality that emerges at the Viennese fin- de-Siècle, a dialectic that continues to shape both German historiography and the construction of modernity in contemporary scholarship. -

The Fear of Leisure

THE B.B.C. SPEECH ON SOCIAL CREDIT Broadcast in the ‘Poverty in Plenty’ series November 5th, 1934 THE FEAR OF LEISURE An Address to the Leisure Society BY A. R. ORAGE INTRODUCTION L. Denis Byrne Introduction It is indeed a privilege to have known Alfred Richard Orage and to write these few lines of introduction, for in a very real sense he was “the midwife” who brought to birth the world-wide Social Credit Movement. During the early part of the Century, Orage was a literary giant in an era of literary greats in England. Among his friends and associates were Bernard Shaw, G. K. Chesterton, H. G. Wells, Wyndham Lewis, Katherine Mansfield, and others of like stature. As editor of The New Age, despite its limited circulation, Orage’s influence extended throughout the English-speaking world. In 1918, when he first met Major C. H. Douglas, The New Age was the organ of the National Guilds Movement. Once he was convinced of the soundness of Douglas’s ideas, Orage used the columns of The New Age to convince the supporters of the ideal of National Guilds that Social Credit offered an even more fundamentally desirable alternative. Thus, through the influence of The New Age, within a relatively short period the foundation was laid for the world-wide Social Credit Movement in Britain, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. In 1922 Orage retired from active participation in the literary field and went abroad. However, The New Age continued under the editorship of Arthur Brenton to serve as the official organ of the Social Credit Movement. -

August Aichhorn „Der Beginn Psychoanalytischer Sozialarbeit“

soziales_kapital wissenschaftliches journal österreichischer fachhochschul-studiengänge soziale arbeit Nr. 12 (2014) / Rubrik "Geschichte der Sozialarbeit" / Standort Graz Printversion: http://www.soziales-kapital.at/index.php/sozialeskapital/article/viewFile/332/579.pdf Thomas Aichhorn: August Aichhorn „Der Beginn psychoanalytischer Sozialarbeit“ Es mag verwundern, den Beginn der psychoanalytischen Sozialarbeit mit einer Person – August Aichhorn – zu verknüpfen, die in der Regel eher der Pädagogik als der Sozialarbeit zugerechnet wird. Ich berufe mich dabei auf Ernst Federn1, der selbst Sozialarbeiter war und Aichhorn gut kannte. Er behauptete kurz und bündig: „Psychoanalytische Sozialarbeit […] begann mit der Betreuung delinquenter und verwahrloster Jugendlicher in den 20iger Jahren durch August Aichhorn in Wien.“2 Und in seiner Arbeit „August Aichhorns’s work as a contribution to the theory and practice of Case Work Therapy“3 hatte er geschrieben: „Jeder, der nach Konzepten für die Sozialarbeit sucht und hofft, Anregungen dazu in Freuds Entdeckungen zu finden, sollte zunächst und vor allem die Arbeiten des Mannes lesen und studieren, der sein Leben nicht nur der Anwendung der Psychoanalyse auf die Sozialarbeit gewidmet hat, sondern der auch der erste Sozialarbeiter war, der zugleich Psychoanalytiker gewesen ist. Man sollte sich auch daran erinnern, dass er als Person und in seiner Arbeit von Freud selbst uneingeschränkt unterstützt wurde“ (ebd.: 17f).4 Die Auffassung, was Sozialarbeit sei, war und ist, ist abhängig vom gesellschaftlich- politischen Rahmen, in dem sie stattfindet. Aichhorn war sich nur zu gut der Tatsache bewusst, dass er sich mit seinem Arbeitsansatz in eklatantem Widerspruch zu allen politischen Systemen der Zeit befand, in der er lebte und arbeitete. Er war zwar verschiedentlich in amtlicher Stellung tätig, aber keiner seiner Vorgesetzten hatte jemals seine Arbeit unterstützt. -

Ramiro De Maeztu En La Redacción De the New

RAMIRO DE MAEZTU Y LA REDACCIÓN DE THE NEW AGE: EL IMPACTO DE LA I GUERRA MUNDIAL SOBRE UNA GENERACIÓN DE INTELECTUALES. Andrea Rinaldi University of Bergen Introducción The New Age fue publicada por primera vez en Londres en 1894, y era el principal medio de comunicación de la Sociedad Fabiana, un movimiento de opinión democrático y socialista, vinculado al Partido Laborista, en cuyas filas destacaron intelectuales como George Bernard Shaw, Virginia Woolf y Bertrand Russell. La revista obtuvo rápidamente éxito entre los intelectuales británicos, y lo conservó por lo menos durante las dos primeras décadas del siglo pasado. En 1907 The New Age, bajo la dirección de Joseph Clayton, adquirió un tinte bastante radical que no acababa de encajar con el reformismo gradualista de los fabianos, por lo que la revista sufrió una fuerte caída en las ventas. En mayo del mismo año, dos intelectuales hasta entonces no muy conocidos, Alfred Richard Orage y George Holbrook Jackson, relevaron la revista; los dos consiguieron entrar en la dirección gracias a la ayuda económica de Shaw, que decidió cederles parte de los derechos de autor de la exitosa comedia The Doctor’s Dilemma, y también gracias a la contribución del financiero Lewis Wallace1. Orage era un exprofesor de instituto de Leeds, que había trabajado, junto al mismo Jackson y a Arthur J. Penty, para el Leeds Art Club, un círculo cultural muy activo en la preparación de conferencias de temas varios (política, filosofía, religión, ocultismo, arte, etc.) en las que participaban intelectuales del rango de Yeats o el mismo Shaw. Orage consiguió hacerse rápidamente con el mando exclusivo de la revista; de hecho, Jackson trabajó como coeditor sólo durante el primer año, mientras que Orage fue el único director hasta 1922, año en que decidió venderla2. -

A Feminist Economist?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Marouzi, Soroush Working Paper Frank Plumpton Ramsey: A feminist economist? CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2021-09 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Marouzi, Soroush (2021) : Frank Plumpton Ramsey: A feminist economist?, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2021-09, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3854782 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234320 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Frank Plumpton Ramsey: A Feminist Economist? Soroush Marouzi CHOPE Working Paper No. 2021-09 May 2021 FRANK PLUMPTON RAMSEY: A FEMINIST ECONOMIST? BY Soroush Marouzi* Abstract: This paper is an attempt to historicize Frank Plumpton Ramsey’s Apostle talks delivered from 1923 to 1925 within the social and political context of the time.