Automobile History Does Not Rival Even That of Its Near Neighbors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEST in SHOW Year Make and Model Award Owner City State 1937 Cadillac Series 90 Founder Trophy Best in Show

BEST IN SHOW Year Make and Model Award Owner City State 1937 Cadillac Series 90 Founder Trophy Best in Show--American Jim Patterson/The Patterson Collection Louisville KY 1953 Ferrari 250MM Founder Trophy Best in Show--Foreign Cultivated Collector New Canaan CT BEST IN CLASS AWARD WINNERS Year Make and Model Class Owner City State 1905 REO Runabout (A) Gas Light-Best in Class Mark Turner Wixom MI 1962 Lincoln Continental (CT) The Continental 1939-Present Best in Class Peter Heydon Ann Arbor MI 1934 Packard Super 8 (ACP) American Classic Packard Best in Class Ernst Hillenbrand Fremont OH 1978 Ducati 900SS (MC) Motorcycle - Best in Class Michael and Margaret Simcoe Birmingham MI 1929 Pierce Arrow Model 143 (B) Jazz Age- Best in Class Lyn and Gene Osborne Castle Rock CO 2016 Hand Built Custom Falconer Dodici (BNB) Built Not Bought Best in Class Michael Jahns Bay Harbor MI 1961 Pontiac Ventura (M1) American Post War Best in Class James Wallace West Bloomfield MI 1937 Cadillac V-16 (F) American Classic Closed-Best in Class Dix Garage 1937 Cadillac Series 90 (G) America Classic Open -Best in Class Jim Patterson/The Patterson Collection Louisville KY 1939 Delahaye 135 MS (J) European Classic - Best in Class Mark Hyman St. Louis MO 1930 Cord L-29 (C) Auburn Cord - Best in Class OFF Brothers Collection Richland MI 1929 Duesenberg J 239 (D) Duesenberg - Best in Class Ray Hicks Northville MI 1970 AMC Javelin (N1) Muscle Cars Transitions 1970-71 Best in Class Lee Crum Norwalk OH 1968 Plymouth Barracuda (DR) Drag Cars '63-'73 Super Stock - Best in -

Volume 45 No. 2 2018 $4.00

$4.00 Free to members Volume 45 No. 2 2018 Cars of the Stars National Historic Landmark The Driving Experience Holiday Gift Ideas Cover Story Corporate Members and Sponsors The Model J Dueseberg $5,000 The Model J Duesenberg was introduced at the New York Auto Show December Auburn Gear LLC 1, 1928. The horsepower was rated at 265 and the chassis alone was priced Do it Best Corp. at $8,500. E.L. Cord, the marketing genius he was, reamed of building these automobiles and placing them in the hands of Hollywood celebrities. Cord believed this would generate enough publicity to generate sells. $2,500 • 1931 J-431 Derham Tourster DeKalb Health Therma-Tru Corp. • Originally Cooper was to receive a 1929, J-403 with chassis Number 2425, but a problem with Steel Dynamics, Inc. the engine resulted in a factory switch and engine J403 was replaced by J-431 before it was delivered to Cooper. $1,000 • Only eight of these Toursters were made C&A Tool Engineering, Inc. Gene Davenport Investments • The vehicle still survives and has been restored to its original condition. It is in the collection of the Heritage Museums & Gardens in Sandwich, MA. Hampton Industrial Services, Inc. Joyce Hefty-Covell, State Farm • The instrument panel provided unusual features for the time such as an Insurance altimeter and service warning lights. MacAllister Machinery Company, Inc. Mefford, Weber and Blythe, PC Attorneys at Law Messenger, LLC SCP Limited $500 Auburn Moose Family Center Betz Nursing Home, An American Senior Community Brown & Brown Insurance Agency, Inc. Campbell & Fetter Bank Ceruti’s Catering & Event Planning Gary Cooper and his 1929 Duesenberg J-431 Derham Tourster Farmers & Merchant State Bank Goeglein’s Catering Graphics 3, Inc. -

1931 Duesenberg SJ-488 Convertible Sedan Owned by Tom and Susan Armstrong

Autumn 2008 1931 Duesenberg SJ-488 Convertible Sedan Owned by Tom and Susan Armstrong Pacific Northwest Region -- CCCA Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA Director’s Message 2008 CCCA National Events Winter is fast approaching and many of our Classics are back in their secure garages until the flowers bloom next Spring; at least for us “fair weather” drivers. Annual Meetings In spite of weather, a Director’s 2009 job is never done. The same holds true for your Jan 7-11 . Cincinnati, OH (Indiana Region) Officers, Board of Managers and the folks already 2010 contemplating activities for 2009. Jan TBD . San Diego, CA (SoCal Region) When this issue of the Bumper Guardian is in your hands there will be only two PNR activities Grand Classics® remaining for 2008: the Annual Business Meeting 2009 and the Holiday Party. Please consider being there. Apr 17-19 . Florham Park, NJ (Metro Region) The Managers of both (Ray Loe for the Annual Meeting and Julianna Noble for the Holiday Party) CARavans are working to make these events well worth 2008 attending. Oct 12-18 . Independence Trail (DVR /CBR) This has been an active year for our PNR Region. 2009 From the National Annual Meeting through to and Jun 12-20 . Delta to Desert (NCR) Sept 18-26 . Rivers, Roads and Rhythms (SLR) including the Kirkland Concours the members of our region have been highly involved in the 2010 various activities. Once again I want to express my July TBD . Northwest CARavan (PNR) Sept 9-18 . Autumn in the Adirondacks (MTR) appreciation for all the assistance given to make the National Annual Meeting a great success. -

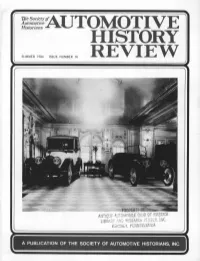

History Review Should Be Two Exceptional Roamers on Display at the Blackstone Hotel in Addressed To: Society of Automotive Chicago, January 1917

'f~;~~~j~~UTOMOTIVE HJstonans· HISTORY SUMMER 1984 ISSUE NUMBER 16 REVIEW A PUBLICATION OF THE SOCIETY OF AUTOMOTIVE HISTORIANS, INC. 2 AUTOMOTIVE HISTORY EDITOR _SUMME_R1984-REVIE",~7 Frederic k D. Roe ISSUE NUMBER 16 •. ~ All correspondence in connection with Two Roamers on Display Front Cover Automotive History Review should be Two exceptional Roamers on display at the Blackstone Hotel in addressed to: Society of Automotive Chicago, January 1917. On the left is the catalogued "Salamanca" Historians, Printing & Publishing type; on the right is the "Cornina," a special design by Karl H. Martin. Photo from the Free Library of Philadelphia collection. Office, 1616 Park Lane, N.E., Marietta, Georgia 30066. Rambler Assembly Line - 1908 2 This photo, contributed by Darwyn H. Lumley, of Placentia, Cali- fornia, shows the assembly room of the Thomas B. Jeffery Company, Kenosha, Wisconsin. Jeffery built the Ram bier car from 1902 through 1913, when the name was changed to "Jeffery." Letters From Our Readers 4 A letter to this department is a letter to the whole membership, and Automotive History Review is a you'll get replies from many of them. Write about anything you wish, semi-annual publication of the Society but write! This can be the most interesting part of the magazine. of Automotive Historians, Inc. Type- Origins of the Roamer 5 setting and layout is by Brigham Books, Fred Roe looks into the origins of this interesting make, and promises Marietta, Georgia 30066. Printing is a follow-up article for a future issue. by Brigham Press, Inc., 1950 Canton Mr. Duryea and the Eaton Manufacturing Company 9 Road, N.E., Marietta, Georgia 30066. -

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019 The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | Friday April 26 and Saturday April 27, 2019 10am BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS 580 Madison Avenue Rupert Banner +1 (212) 644 9001 New York, New York 10022 +1 (917) 340 9652 +1 (212) 644 9009 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90046 Evan Ide From April 23 to 29, to reach us at +1 (917) 340 4657 the Tupelo Automobile Museum: 220 San Bruno Avenue [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6514 San Francisco, California 94103 +1 (212) 644 9009 John Neville +1 (917) 206 1625 bonhams.com/tupelo To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] bonhams.com/tupelo PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION Eric Minoff The Tupelo Automobile Museum +1 (917) 206-1630 Please see pages 4 to 5 and 223 to 225 for 1 Otis Boulevard [email protected] bidder information including Conditions Tupelo, Mississippi 38804 of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Automobilia PREVIEW Toby Wilson AUTOMATED RESULTS SERVICE Thursday April 25 9am - 5pm +44 (0) 8700 273 619 +1 (800) 223 2854 Friday April 26 [email protected] Automobilia 9am - 10am FRONT COVER Motorcars 9am - 6pm General Information Lot 450 Saturday April 27 Gregory Coe Motorcars 9am - 10am +1 (212) 461 6514 BACK COVER [email protected] Lot 465 AUCTION TIMES Friday April 26 Automobilia 10am Gordan Mandich +1 (323) 436 5412 Saturday April 27 Motorcars 10am [email protected] 25593 AUCTION NUMBER: Vehicle Documents Automobilia Lots 1 – 331 Stanley Tam Motorcars Lots 401 – 573 +1 (415) 503 3322 +1 (415) 391 4040 Fax ADMISSION TO PREVIEW AND AUCTION [email protected] Bonhams’ admission fees are listed in the Buyer information section of this catalog on pages 4 and 5. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Four More Legends Join Gooding

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Four more legends join Gooding & Company’s 2012 Pebble Beach Auctions, its greatest collection of automobiles ever assembled SANTA MONICA, Calif. (August 2, 2012) – Gooding & Company, the official auction house of the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance acclaimed for selling the world’s most significant and valuable collector cars, is thrilled to present four automotive icons at its Pebble Beach Auctions on August 18 & 19: the Clark Gable 1935 Duesenberg Model JN Convertible Coupe; the “Green Hornet,” a 1931 Bentley 4 1/2 Litre SC “Blower” Sports 2/3 Seater Boattail; the 1957 Ferrari 250 GT LWB California Spider Prototype and a 1932 Bugatti Type 55 Cabriolet. These extraordinary automobiles, four of the 124 total lots offered, possess exceptional provenance and historical significance, and round out what has become an unparalleled presentation of the finest collector cars ever offered. “What’s incredible about these four cars is that since day one, they have been the ultimate models of sport and luxury for their marques as well as for their time,” says David Gooding, President and Founder of Gooding & Company. “These are the cars that connoisseurs dream about and we’re honored to have the opportunity to present them to the international collecting community later this month.” Clark Gable’s 1935 Duesenberg Model JN Convertible Coupe Originally the property of “The King of Hollywood,” actor Clark Gable In 1935, Gable drove his new Duesenberg to the White Mayfair Ball in Beverly Hills, where he spent a great deal of -

Lambos and Caddies and Rolls-Royces, Oh My! There’S No Place Like the Pacific Northwest Concours D’ Elegance at America’S Car Museum

Lambos and Caddies and Rolls-Royces, Oh My! There’s No Place Like the Pacific Northwest Concours d’ Elegance at America’s Car Museum Contacts: PCG – Shae Collins (424) 903-3647 ([email protected]) ACM – Ashley Bice (253) 683-3954 ([email protected]) TACOMA, Wash. (Sept. 21, 2015) – More than160 vehicles traveled to the largest auto museum in North America to be on display for a weekend of celebrating historic cars at the 13th annual Pacific Northwest Concours d’Elegance. The event at America’s Car Museum (ACM) brought together 1,200 attendees from across the U.S. and Canada for a three-day weekend of auto enthusiast-approved entertainment, including a 100- mile Tour d’ Jour through picturesque roads of Puget Sound, a Dinner d’Elegance with gourmet cuisine from James Beard Award winning chef Tom Douglas and a live and silent auction, and, of course, the Concours. Emceed by Paul Ianuario and Keith Martin, owner of Sports Car Market and winner of the Edward Herman Award, the Concours brought a diverse combination of historic and contemporary collector vehicles from McClaren, Packard, Cord, Ducati and many others. Winner of the Ascent Best of Show Award was the 1932 Auburn Speedster, and Roll-Royce was the featured marque. Among the winners this year were a 1937 Rolls-Royce PIII Tourer in the Elegance of Rolls Royce class, a 1906 Cadillac Runabout in the Antiques class and a 2014 Lamborghini Gallardo Squadra Corse in the Super Cars class. “The Pacific Northwest Concours is always a success when we have such great entrants,” said CEO of ACM, David Madeira. -

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators”

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators” Transportationthehenryford.org in America/education Table of Contents PART 1 PART 2 03 Chapter 1 85 Chapter 1 What Is “American” about American Transportation? 20th-Century Migration and Immigration 06 Chapter 2 92 Chapter 2 Government‘s Role in the Development of Immigration Stories American Transportation 99 Chapter 3 10 Chapter 3 The Great Migration Personal, Public and Commercial Transportation 107 Bibliography 17 Chapter 4 Modes of Transportation 17 Horse-Drawn Vehicles PART 3 30 Railroad 36 Aviation 101 Chapter 1 40 Automobiles Pleasure Travel 40 From the User’s Point of View 124 Bibliography 50 The American Automobile Industry, 1805-2010 60 Auto Issues Today Globalization, Powering Cars of the Future, Vehicles and the Environment, and Modern Manufacturing © 2011 The Henry Ford. This content is offered for personal and educa- 74 Chapter 5 tional use through an “Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike” Creative Transportation Networks Commons. If you have questions or feedback regarding these materials, please contact [email protected]. 81 Bibliography 2 Transportation: Past, Present and Future | “From the Curators” thehenryford.org/education PART 1 Chapter 1 What Is “American” About American Transportation? A society’s transportation system reflects the society’s values, Large cities like Cincinnati and smaller ones like Flint, attitudes, aspirations, resources and physical environment. Michigan, and Mifflinburg, Pennsylvania, turned them out Some of the best examples of uniquely American transporta- by the thousands, often utilizing special-purpose woodwork- tion stories involve: ing machines from the burgeoning American machinery industry. By 1900, buggy makers were turning out over • The American attitude toward individual freedom 500,000 each year, and Sears, Roebuck was selling them for • The American “culture of haste” under $25. -

Finding Aid for the Henry Austin Clark Jr. Photograph Collection, 1853-1988

Finding Aid for HENRY AUSTIN CLARK JR. PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION, 1853-1988 Accession 1774 Finding Aid Published: May 2014 Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org Henry Austin Clark Jr. Photograph collection Accession 1774 OVERVIEW REPOSITORY: Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Blvd Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 www.thehenryford.org [email protected] ACCESSION NUMBER: 1774 CREATOR: Clark, Henry Austin, Jr., 1917-1991 TITLE: Henry Austin Clark Jr. Photograph collection INCLUSIVE DATES: 1853-1988 QUANTITY: 25.6 cubic ft. and 185 oversize boxes LANGUAGE: The materials are in English ABSTRACT: The photograph collection of Henry Austin Clark Jr. collector, museum owner and devotee, documents the history of the automobile in Europe and the United States. Page 2 of 67 Updated 5.16.2014 Henry Austin Clark Jr. Photograph collection Accession 1774 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: The collection is open for research TECHNICAL RESTRICTIONS: Access to original motion pictures is restricted. Digital copies are available for use in the Benson Ford Research Center Reading Room. COPYRIGHT: Copyright has been transferred to the Henry Ford by the donor. Copyright for some items in the collection may still be held by their respective creator(s). ACQUISITION: Donated, 1992 RELATED MATERIAL: Related material held by The Henry Ford includes: - Henry Austin Clark Jr. papers, Accession 1764 - Henry Austin Clark Jr. Automotive-related programs collection, Accession 1708 PREFERRED CITATION: Item, folder, box, Accession 1774, Henry Austin Clark Jr. photograph collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford PROCESSING INFORMATION: Collection processed by Benson Ford Research Center staff, 1992-2005 DESCRIPTION INFORMATION: Original collection inventory list prepared by Benson Ford Research Center staff, 1995-2005, and published in January, 2011. -

Automobile) 12

AACA 1. AACA Events Coachbuilders 2. Events Elegance • Coachbuilders (history, general) 3. History Committee 1. Abbott, E.D. 4. Library 2. Accossatto 5. Library Auction 3. Ackley, L.M. 6. Merchandise 4. ACG 7. Museum 5. Acme Wagon 8. National Awards Committee 6. Aerocell 9. National Board 7. A.H.A. 10. Presidents 8. Alcoa Aluminum 11. Regions History 9. Allegheny Ludlum 12. Registration – Antique Auto 10. Alden, Fisk 11. American Coach & Body Clubs & Organizations (Automobile) 12. American Wagon 1. AAA (American Automobile Assoc.) 13. America’s Body Co. 2. Auburn Cord Duesenberg Club 14. American Custom 3. Automobile Club of America (ACA) 15. Ames Body 4. Automobile Manufacturers Association (AMA) 16. Ansart & Teisseire 5. Automobile Clubs – Australia 17. Armbruster Stageway 6. Bugatti Owner’s Club 18. ASC 7. Classic Car Club of America (CCCA) 19. A.T. DeMarest 8. CCCA Midwest 20. Auburn 9. Cross Country Motor Club 21. Audineau, Paul 10. FIVA (Federation Internationale des Vehicules 22. Automotive Body Company Anciens) 23. Avon Body Co. 11. Horseless Carriage Club of America (HCCA) 24. Babcock, H.H. 12. Lincoln Continental Owner’s Club 25. Baker Raulang 13. Mercedes-Benz Club of America 26. Balbo 14. Automobile Club – Michigan 27. Barclay 15. Automobile Clubs – Misc. 28. Barker 16. Model T Ford Club International 29. Bekvallete 17. Motorcycle Minute Men of America (WWI) 30. Berkeley 18. MVMA (Motor Vehicle Manuf. Assoc.) 31. Bernath 19. New Zealand - Automobile Clubs – New Zealand 32. Bertone 20. Packard Club 33. Biddle & Smart 21. Philadelphia - Automobile Clubs – Philadelphia 34. Bivouac 22. Royal Automobile Club – London 35. -

Report of Contracting Activity

Vendor Name Address Vendor Contact Vendor Phone Email Address Total Amount 1213 U STREET LLC /T/A BEN'S 1213 U ST., NW WASHINGTON DC 20009 VIRGINIA ALI 202-667-909 $3,181.75 350 ROCKWOOD DRIVE SOUTHINGTON CT 13TH JUROR, LLC 6489 REGINALD F. ALLARD, JR. 860-621-1013 $7,675.00 1417 N STREET NWCOOPERATIVE 1417 N ST NW COOPERATIVE WASHINGTON DC 20005 SILVIA SALAZAR 202-412-3244 $156,751.68 1133 15TH STREET NW, 12TH FL12TH FLOOR 1776 CAMPUS, INC. WASHINGTON DC 20005 BRITTANY HEYD 703-597-5237 [email protected] $200,000.00 6230 3rd Street NWSuite 2 Washington DC 1919 Calvert Street LLC 20011 Cheryl Davis 202-722-7423 $1,740,577.50 4606 16TH STREET, NW WASHINGTON DC 19TH STREET BAPTIST CHRUCH 20011 ROBIN SMITH 202-829-2773 $3,200.00 2013 H ST NWSTE 300 WASHINGTON DC 2013 HOLDINGS, INC 20006 NANCY SOUTHERS 202-454-1220 $5,000.00 3900 MILITARY ROAD NW WASHINGTON DC 202 COMMUNICATIONS INC. 20015 MIKE HEFFNER 202-244-8700 [email protected] $31,169.00 1010 NW 52ND TERRACEPO BOX 8593 TOPEAK 20-20 CAPTIONING & REPORTING KS 66608 JEANETTE CHRISTIAN 785-286-2730 [email protected] $3,120.00 21C3 LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT LL 11 WATERFORD CIRCLE HAMPTON VA 23666 KIPP ROGERS 757-503-5559 [email protected] $9,500.00 1816 12TH STREET NW WASHINGTON DC 21ST CENTURY SCHOOL FUND 20009 MARY FILARDO 202-745-3745 [email protected] $303,200.00 1550 CATON CENTER DRIVE, 21ST CENTURY SECURITY, LLC #ADBA/PROSHRED SECURITY BALTIMORE MD C. MARTIN FISHER 410-242-9224 $14,326.25 22 Atlantic Street CoOp 22 Atlantic Street SE Washington DC 20032 LaVerne Grant 202-409-1813 $2,899,682.00 11701 BOWMAN GREEN DRIVE RESTON VA 2228 MLK LLC 20190 CHRIS GAELER 703-581-6109 $218,182.28 1651 Old Meadow RoadSuite 305 McLean VA 2321 4th Street LLC 22102 Jim Edmondson 703-893-303 $13,612,478.00 722 12TH STREET NWFLOOR 3 WASHINGTON 270 STRATEGIES INC DC 20005 LENORA HANKS 312-618-1614 [email protected] $60,000.00 2ND LOGIC, LLC 10405 OVERGATE PLACE POTOMAC MD 20854 REZA SAFAMEJAD 202-827-7420 [email protected] $58,500.00 3119 Martin Luther King Jr. -

List of Agents by County for the Web

List of Agents By County for the Web Agent (Full) Services for Web Run Date: 10/1/2021 Run Time: 7:05:44 AM ADAMS COUNTY Name Street Address City State Zip Code Phone 194 IMPORTS INC 680 HANOVER PIKE LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-7752 30 WEST AUTO SALES INC 1980 CHAMBERSBURG RD GETTYSBURG PA 17325 717-334-3300 97 AUTO SALES 4931 BALTIMORE PIKE LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-9536 AAA CENTRAL PENN 1275 YORK RD GETTYSBURG PA 17325 717-334-1155 A & A AUTO SALVAGE INC 1680 CHAMBERSBURG RD GETTYSBURG PA 17325 717-334-3905 A & C USED AUTO 131 FLICKINGER RD GETTYSBURG PA 17325 717-334-0777 ADAMIK INSURANCE AGENCY INC 5356 BALTIMORE PIKE # A LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-7744 A & D BUSINESS SERVICES LLC 12 WATER ST FAIRFIELD PA 17320 - 8252 717-457-0551 ADELA TOVAR CAMPUZANO DBA MANZOS 190 PARK ST ASPERS PA 17304 - 9602 717-778-1773 MOTORS 500 MAIN STREET ALLENWRENCH AUTOMOTIVE YORK SPRINGS PA 17372 717-528-4134 PO BOX 325 AMIG AUTO AND TRUCK SALES 4919 YORK RD NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-8814 AUTOS ARE US AUTO SALES LLC 631A W KING ST ABBOTTSTOWN PA 17301 717-259-9950 BANKERTS AUTO SALES 3001 HANOVER PIKE HANOVER PA 17331 717-632-8464 BATTLEFIELD MOTORCYCLES INC 21 CAVALRY FIELD RD GETTYSBURG PA 17325 717-337-9005 BERLINS LLC 130 E KING ST EAST BERLIN PA 17316 717-619-7725 Page 1 of 536 List of Agents By County for the Web Run Date: 10/1/2021 Run Time: 7:05:44 AM ADAMS COUNTY Name Street Address City State Zip Code Phone BERMEJO AUTO SALES LLC 4467 YORK RD NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-2424 BETTY DIANE SHIPLEY 1155 700 RD NEW OXFORD PA 17350 -- BOWERS