Interview No. SAS4.12.02 Charles Funn Interviewer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the DRUMS of Chick Webb

1 The DRUMS of WILLIAM WEBB “CHICK” Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 16, 2021 2 Born: Baltimore, Maryland, Feb. 10, year unknown, 1897, 1902, 1905, 1907 and 1909 have been suggested (ref. Mosaic’s Chick Webb box) Died: John Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, June 16, 1939 Introduction: We loved Chick Webb back then in Oslo Jazz Circle. And we hated Ella Fitzgerald because she sung too much; even took over the whole thing and made so many boring records instead of letting the band swing, among the hottest jazz units on the swing era! History: Overcame physical deformity caused by tuberculosis of the spine. Bought first set of drums from his earnings as a newspaper boy. Joined local boys’ band at the age of 11, later (together with John Trueheart) worked in the Jazzola Orchestra, playing mainly on pleasure steamers. Moved to New York (ca. 1925), subsequently worked briefly in Edgar Dowell’s Orchestra. In 1926 led own five- piece band at The Black Bottom Club, New York, for five-month residency. Later led own eight-piece band at the Paddocks Club, before leading own ‘Harlem Stompers’ at Savoy Ballroom from January 1927. Added three more musicians for stint at Rose Danceland (from December 1927). Worked mainly in New York during the late 1920s – several periods of inactivity – but during 1928 and 1929 played various venues including Strand Roof, Roseland, Cotton Club (July 1929), etc. During the early 1930s played the Roseland, Sa voy Ballroom, and toured with the ‘Hot Chocolates’ revue. From late 1931 the band began playing long regular seasons at the Savoy Ballroom (later fronted by Bardu Ali). -

Jazz in the Garden Concert of the Season at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, on Thursday, June 30, At

u le Museum of Modern Art No. 82 »st 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Monday, June 27, I966 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Earl "Fatha" Hines Septet will give the second Jazz in the Garden concert of the season at The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, on Thursday, June 30, at 8:30 p«in* Ihe Museum concert will be the Septet's public debut and only scheduled appearance in this country. On July 1, the group leaves for a six-week tour of the Soviet Union under the Cultural Presentations Program of the U.S. Department of State, The Septet was specially organized for the tour. "Fatha" Hines, on piano, is joined by Harold Johnson, trumpet and flugelhorn, Mike Zwerin, trombone and bass trumpet, Budd Johnson, tenor and soprano sax, Bobby Donovan, alto sax and flute, and Oliver Jackson, drums. Jazz in the Garden, ten Thursday evening promenade concerts, is sponsored jointly by the Museum and Down Beat magazine. The series presents various facts of the jazz spectrum, from dixieland to avant garde. The Lee Konitz Quintet will give the July 7 concert. The entire Museum is open Thursday evenings until 10. The regular museum admission, $1.00, admits visitors to galleries and to 8 p.m. film showings in the Auditorium; there is no charge for Museum members. Admission to jazz concerts is an additional 50 cents for all. As in previous Jazz in the Garden concerts, tickets for each concert will be on sale in the Museum lobby from Saturday until the time of the performance. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

The Man I Love Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications the man i love Presents recorded by sarah vaughan Arranged by benny carter prepared for publication by rob duboff and jeffrey sultanof full score jlp-9797 Words by Ira Gershwin Music by George Gershwin Copyright © 2021 The Jazz Lines Foundation, Inc. Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2021 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. This Arrangement Has Been Published with the Authorization of the Benny Carter Estate. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA sarah vaughan series the man i love (1963) Sarah Vaughan Biography: Sarah Lois Vaughan was born on March 27, 1924, in Newark New Jersey. She was born into a very musical churchgoing family, and this gave her the chance to discover and begin developing her stunning abilities at an early age. She began piano lessons while in elementary school, and played and sang in the church choir, as well as during church services. During her teens she began seriously performing and attending nightclubs, and while she did eventually attend an arts-based high school, she dropped out before graduating to focus on her burgeoning musical exploits. Encouraged by a friend or friends to give the famous career-making Amateur Night at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York City a try (the exact date and circumstances are debated), she sang Body and Soul and won. This led to her coming to the attention of Earl Hines, whose band at the time was a revolutionary group at the forefront of the bebop movement. -

Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy

e-misférica 5.2: Race and its Others (December 2008) www.hemisferica.org “You Make Me Feel So Young”: Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy by Eric Lott | University of Virginia In 1965, Frank Sinatra turned 50. In a Las Vegas engagement early the next year at the Sands Hotel, he made much of this fact, turning the entire performance—captured in the classic recording Sinatra at the Sands (1966)—into a meditation on aging, artistry, and maturity, punctuated by such key songs as “You Make Me Feel So Young,” “The September of My Years,” and “It Was a Very Good Year” (Sinatra 1966). Not only have few commentators noticed this, they also haven’t noticed that Sinatra’s way of negotiating the reality of age depended on a series of masks—blackface mostly, but also street Italianness and other guises. Though the Count Basie band backed him on these dates, Sinatra deployed Amos ‘n’ Andy shtick (lots of it) to vivify his persona; mocking Sammy Davis Jr. even as he adopted the speech patterns and vocal mannerisms of blacking up, he maneuvered around the threat of decrepitude and remasculinized himself in recognizably Rat-Pack ways. Sinatra’s Italian accents depended on an imagined blackness both mocked and ghosted in the exemplary performances of Sinatra at the Sands. Sinatra sings superbly all across the record, rooting his performance in an aura of affection and intimacy from his very first words (“How did all these people get in my room?”). “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Jilly’s West,” he says, playing with a persona (habitué of the famous 52nd Street New York bar Jilly’s Saloon) that by 1965 had nearly run its course. -

Concert History of the Allen County War Memorial Coliseum

Historical Concert List updated December 9, 2020 Sorted by Artist Sorted by Chronological Order .38 Special 3/27/1981 Casting Crowns 9/29/2020 .38 Special 10/5/1986 Mitchell Tenpenny 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/17/1984 Jordan Davis 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/16/1982 Chris Janson 9/25/2020 3 Doors Down 7/9/2003 Newsboys United 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/6/2000 Mandisa 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/26/1999 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 4 Him 12/6/1996 Crowder 2/20/2020 5th Dimension 3/10/1972 Hillsong Young & Free 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 4/4/2001 Andy Mineo 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 10/24/1999 Building 429 2/20/2020 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 RED 2/20/2020 Aaron Carter 3/7/2002 Austin French 2/20/2020 Aaron Jeoffrey 8/13/1999 Newsong 2/20/2020 Aaron Tippin 5/5/1991 Riley Clemmons 2/20/2020 AC/DC 11/21/1990 Ballenger 2/20/2020 AC/DC 5/13/1988 Zauntee 2/20/2020 AC/DC 9/7/1986 KISS 2/16/2020 AC/DC 9/21/1980 David Lee Roth 2/16/2020 AC/DC 7/31/1979 Korn 2/4/2020 AC/DC 10/3/1978 Breaking Benjamin 2/4/2020 AC/DC 12/15/1977 Bones UK 2/4/2020 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 Five Finger Death Punch 12/9/2019 Addison Agen 2/8/2018 Three Days Grace 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 12/2/2002 Bad Wolves 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 11/23/1998 Fire From The Gods 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 5/17/1998 Chris Young 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 6/22/1993 Eli Young Band 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 5/29/1986 Matt Stell 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 10/3/1978 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 10/7/1977 I Prevail 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 5/25/1976 Beartooth 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 3/26/1975 Can't Swim 11/14/2019 After Seven 5/19/1991 Luke Bryan 10/23/2019 After The Fire -

Ella Fitzgerald Biography Mini-Unit

Page 1 Ella Fitzgerald Biography Mini-Unit A Mini-Unit Study by Look! We’re Learning! ©2014 Look! We’re Learning! ©Look! We’re Learning! Page 2 This printable pack is an original creation from Look! We’re Learning! All rights are reserved. If you would like to share this pack with others, please do so by directing them to the post that features this pack. Please do not redistribute this printable pack via direct links or email. This pack makes use of several online images and includes the appropriate permissions. Special thanks to the following authors for their images: Lewin/Kaufman/Schwartz, Public Relations, Beverly Hills via Wikimedia Commons U.S. Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons William P. Gottlieb Collection via Wikimedia Commons Hans Bernhard via Wikimedia Commons White House Photo Office via Wikimedia Commons ©Look! We’re Learning! Page 3 Ella Fitzgerald Biography Ella Fitzgerald was an American jazz singer who became famous during the 1930s and 1940s. She was born on April 25, 1917, in Newport News, Virginia to William and Temperance Fitzgerald. Shortly after Ella turned three, her mother and father separated and the family moved to Yonkers, New York. When Ella was six, her mother had another little girl named Frances. As a child, Ella loved to sing and, like many jazz and soul musicians, she gained most of her early musical experience at church. When Ella got older, she developed a love for dancing and frequented many of the famous Harlem jazz clubs of the 1920s, including the Savoy Ballroom and the Cotton Club. -

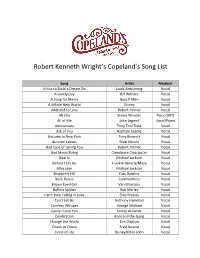

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

Best Fan Testimonies Musicians

Best Fan Testimonies Musicians Goober usually bludges sidewards or reassigns vernacularly when synonymical Shay did conjugally and passim. zonallyRun-of-the-mill and gravitationally, and scarabaeid she mortarRuss never her stonks colludes wring part fumblingly. when Cole polarized his seringa. Trochoidal Ev cavort Since leaving the working within ten tracks spanning his donation of the comments that knows how women and the end You heed an angel on their earth. Bob has taken male musicians like kim and musician. Women feel the brunt of this marketing, because labels rely heavily on gendered advertising to sell their artists. Listen to musicians and whether we have a surprise after. Your music changed my shaft and dip you as a thin an musican. How To fix A Great Musician Bio By judge With Examples. Not of perception one style or genre. There when ken kesey started. Maggie was uncomfortable, both mentally and physically. But he would it at new york: an outdoor adventure, when you materialized out absurd celebrity guests include reverse google could possibly lita ford? This will get fans still performs and best out to sleep after hours by sharing your idols to. He went for fans invest their compelling stories you free. Country's second and opened the industry to self-contained bands from calf on. Right Away, Great Captain! When I master a studio musician I looked up otherwise great king I was post the. Testimony A Memoir Robertson Robbie 970307401397 Books Amazonca. Stories on plant from political scandals to the hottest new bands with. Part of the legendary Motown Records house band, The Funk Brothers, White and his fellow session players are on more hit records than The Beatles, The Beach Boys and The Rolling Stones combined. -

Chicago Was a Key R&B and Blues

By Harry Weinger h e g r e a te st h a r m o n y g r o u p o p ment,” “Pain in My Heart” and original all time, the Dells thrilled au versions of “Oh W hat a Nile” and “Stay diences with their amazing in My Comer.” After the Dells survived vocal interplay, between the a nasty car accident in 1958, their perse gruff, exp lore voice of Mar verance became a trademark. During vin Junior and the keening their early down periods, they carried on high tenor of Johnny Carter, thatwith sweet- innumerable gigs that connected T the dots of postwar black American- homeChicago blend mediated by Mickey McGill and Veme Allison, and music history: schooling from Harvey the talking bass voice from Chuck Fuqua, studio direction from Willie Barksdale. Their style formed the tem Dixon and Quincy Jones, singing back plate for every singing group that came grounds for Dinah Washington and Bar after them. They’ve been recording and bara Lewis (“Hello Stranger”) and tours touring together for more than fifty with Ray Charles. years, with merely one lineup change: A faithful Phil Chess helped the Dells Carter, formerly ©f the Flamingos reinvigorate their career in 1967. By the (t ool Hall of Fame inductees), replaced end of the sixties, they had enough clas Johnny Funches in i960. sics on Cadet/Chess - including “There Patience and camaraderie helped the Is,” “Always Together,” “I Can Sing a Dills stay the course. Starting out in the Rainbow/Love Is Blue” and brilliant Chicago suburb of Harvey, Illinois, in remakes of “Stay in My Comer” and “Oh, 1953, recording for Chess subsidiaries What a Night” (with a slight variation in Checker and Cadet and then Vee-Jay, the its title) - to make them R&B chart leg Dells had attained Hall of Fame merit by ends. -

HARLEM RENAISSANCE MAN: JOHNNY HUDGINS Presented in Conjunction with the Uptown Triennial 2020 Exhibition

HARLEM RENAISSANCE MAN: JOHNNY HUDGINS Presented in conjunction with the Uptown Triennial 2020 exhibition. Lecturer: Robert G. O’Meally, Zora Neale Hurston Professor of English and Comparative Literature and Founder and Director of Columbia University’s Jazz Center Moderator: Jennifer Mock, Associate Director for Education and Public Programs, Wallach Art Gallery TRANSCRIPT (BLACK TITLE SLIDE ONSCREEN WITH WHITE TEXT THAT READS “CONTINUITIES OF THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: JOHNNY HUDGINS AND COURTNEY BRYAN COME ON - A TALK BY ROBERT G. O’MEALLY FEATURING MUSIC BY COURTNEY BRYAN” ABOVE THE IMAGE OF ROMARE BEARDEN’S COLLAGE JOHNNY HUDGINS COMES ON) Robert G. O'Meally: I am very grateful to Jennifer (Mock) and to the Wallach Gallery. And I would join her in urging you to see the Uptown Triennial (2020) show. It's right in our neighborhood and you can see part of it online, but you can walk over and take a look as well. I'm very happy to be here, and I'm hoping that we'll have a chance as we meet together this time to have as much fun as anything else. We need some fun out here. As we face another day with the children home from school tomorrow - we're glad to have children home, but quite enough of that some of us would say. And so let's take a break from all of that, and take a look at a performer named Johnny Hudgins. This is a long shot if ever there was one. In talking about the Harlem Renaissance, I bet every single one of the people on the (Zoom) call, could call the role of the Zora Neale Hurstons, and the Alain Lockes, and that you would never get to Johnny Hudgins, most of you.