Doktori Disszertáció

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozaicul Voivodinean – Fragmente Din Cultura Comunităților Naționale Din Voivodina – Ediția Întâi © Autori: Aleksandr

Mozaicul voivodinean – fragmente din cultura comunităților naționale din Voivodina – Ediția întâi © Autori: Aleksandra Popović Zoltan Arđelan © Editor: Secretariatul Provincial pentru Educație, Reglementări, Adminstrație și Minorități Naționale -Comunități Naționale © Сoeditor: Institutul de Editură „Forum”, Novi Sad Referent: prof. univ. dr. Žolt Lazar Redactorul ediției: Bojan Gregurić Redactarea grafică și pregătirea pentru tipar: Administrația pentru Afaceri Comune a Organelor Provinciale Coperta și designul: Administrația pentru Afaceri Comune a Organelor Provinciale Traducere în limba română: Mircea Măran Lectorul ediției în limba română: Florina Vinca Ilustrații: Pal Lephaft Fotografiile au fost oferite de arhivele: - Institutului Provincial pentru Protejarea Monumentelor Culturale - Muzeului Voivodinei - Muzeului Municipiului Novi Sad - Muzeului municipiului Subotica - Ivan Kukutov - Nedeljko Marković REPUBLICA SERBIA – PROVINCIA AUTONOMĂ VOIVODINA Secretariatul Provincial pentru Educație, Reglementări, Adminstrație și Minorități Naționale -Comunități Naționale Proiectul AFIRMAREA MULTICULTURALISMULUI ȘI A TOLERANȚEI ÎN VOIVODINA SUBPROIECT „CÂT DE BINE NE CUNOAŞTEM” Tiraj: 150 exemplare Novi Sad 2019 1 PREFAȚĂ AUTORILOR A povesti povestea despre Voivodina nu este ușor. A menționa și a cuprinde tot ceea ce face ca acest spațiu să fie unic, recognoscibil și specific, aproape că este imposibil. În timp ce faceți cunoștință cu specificurile acesteia care i-au inspirat secole în șir pe locuitorii ei și cu operele oamenilor de seamă care provin de aci, vi se deschid și ramifică noi drumuri de investigație, gândire și înțelegere a câmpiei voivodinene. Tocmai din această cauză, nici autorii prezentei cărți n-au fost pretențioși în intenția de a prezenta tot ceea ce Voivodina a fost și este. Mai întâi, aceasta nu este o carte despre istoria Voivodinei, și deci, nu oferă o prezentare detaliată a istoriei furtunoase a acestei părți a Câmpiei Panonice. -

Sećanje Na Paju Jovanovića I Konstantina Babića: Katalog

УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ У НИШУ ФАКУЛТЕТ УМЕТНОСТИ У НИШУ Весна Гагић Сећање на Пају јовановића и Константина Бабића: каталог биографске изложбе и библиографија радова НИШ, 2020. Весна Гагић Vesna Gagić СEЋAЊE НA ПAJУ JOВAНOВИЋA И КOНСТAНТИНA БAБИЋA: IN REMEMBRANCE OF PAJA JOVANOVIĆ AND KONSTANTIN КAТAЛOГ БИOГРAФСКE ИЗЛOЖБE И БИБЛИOГРAФИJA BABIĆ: THE BIOGRAPHICAL EXHIBITION CATALOGUE AND РAДOВA THE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS Прво издање, Ниш, 2020. First edition, Niš, 2020.. Рецензенти Reviewers мр Перица Донков, ред. проф. Факултета уметности Универзитета у Нишу Perica Donkov, MA, Full professor at the Faculty of Arts, University of Niš др Jeлeнa Цвeткoвић Црвeницa, ванр. проф. Факултета уметности Jelena Cvetković Crvenica, PhD, Associate professor at the Faculty of Arts, University Универзитета у Нишу of Niš др Tатјана Брзуловић Станисављевић, библиотекар саветник Универзитетске Tatjana Brzulović Stanisavljević, PhD, Librarian-consultant of the University Library библиотеке „Светозар Марковић”, Београд Svetozar Marković, Belgrade Рецензенти из области музике за приложени стручни рад Reviewers in the field of music for the attached professional works др Наташа Нагорни Петров, ванр. проф. Факултета уметности Универзитета Nataša Nagorni Petrov, PhD, Associate professor at the Faculty of Arts, у Нишу University of Nis мр Марко Миленковић, доцент Факултета уметности Универзитета у Нишу Marko Milenković, MA, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Arts, University of Niš Издавач Publisher УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ У НИШУ УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ У НИШУ ФАКУЛТЕТ УМЕТНОСТИ У НИШУ ФАКУЛТЕТ -

Winter 2017 Issue

Upcoming Exhibitions WINTER 2018 MORE THAN SELF: LIVING THE VIETNAM WAR Cyclorama RESTORATION UPDATES Physical Updates OLGUITA’S GARDEN Visitor Experiences MIDTOWN ENGAGEMENT Partnerships ATL COLLECTIVE WINTER 2018 WINTER 2017 HISTORY MATTERS . TABLE OF CONTENTS 02–07 22–23 Introduction Kids Creations More than Self: Living the Vietnam War Living the Vietnam than Self: More 08–15 24–27 Exhibition Updates FY17 in Review 16–18 28 Physical Updates Accolades 19 29–33 Midtown Engagement History Makers Cover Image | Boots worn by American soldier in Vietnam War and featured in exhibition, in exhibition, and featured War American soldier in Vietnam by Image worn | Boots Cover 20–21 34–35 Partnerships Operations & Leadership ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER WINTER 2017 NEWSLETTER INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION History is complex, hopeful, and full of fascinating stories of As I walk through the new spaces of our campus, I think back everyday individuals. The people who have created the story of Atlanta through 91 years of institutional history. We should all be proud and are both remarkable and historic. The Atlanta History Center, has amazed at the achievements and ongoing changes that have taken done a great job of sharing the comprehensive stories of Atlanta, place since a small group of 14 historically minded citizens gathered in MESSAGE our region, and its people to the more than 270,000 individuals we MESSAGE 1926 to found the Atlanta Historical Society, which has since become serve annually. Atlanta History Center. The scope and impact of the Atlanta History Center has expanded As Atlanta’s History Center of today, we understand we must find significantly, and we have reached significant milestones. -

Faqs on the Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama Move

FAQs on Atlanta History Center’s Move Why is The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting moving to of The Atlanta History Center? Battle of In July 2014, Mayor Kasim Reed announced the relocation Atlanta and the restoration of this historic Atlanta Cyclorama painting Cyclorama The Battle of Atlanta to the History Center, as part of a 75 Painting year license agreement with the City of Atlanta. Atlanta History Center has the most comprehensive collection of Civil War artifacts at one location in the nation, including the comprehensive exhibition Turning Point: The American Civil War, providing the opportunity to make new connections between the Cyclorama and other artifacts, archival records, photographs, rare books, and contemporary research. As new stewards of the painting, Atlanta History Center provides a unique opportunity to renew one of the city’s most important cultural and historic artifacts. Where will the painting and locomotive be located at the History Center? The Battle of Atlanta painting will be housed in a custom– built, museum-quality environment, in the Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building, located near the corner of West Paces Ferry Road and Slaton Drive, directly behind Veterans Park, and connected to the Atlanta History Museum atrium through Centennial Olympic Games Museum hallway. The Texas locomotive will be displayed in a 2,000-square-foot glass-fronted gallery connecting Atlanta History Museum with the new cyclorama building. What is the condition of the painting? “Better than you might think,” said Gordon Jones, Atlanta History Center Senior Military Historian and a co-leader of the Cyclorama project team. -

03-2007 -...:: Donaudeutsche

DONAUDEUTSCHE Mitteilungen für die Banater Schwaben, Donauschwaben und Deutschen aus Ungarn Folge 3 – Juni 2007 – 53. Jahrgang An der Donau entlang in die alte Heimat uf Ulmer Schachteln fuhren vor über 250 Gruppe und die kulturelle Betätigung. Es war ner Heimat“. Nach dem Festgottesdienst tanz- AJahren unsere Vorfahren die Donau hinab schon etwas schwierig die sprachlichen Proble- ten beide Gruppen auf dem Platz vor der Kirche um eine neue Heimat zu finden. Wir, Mitglieder me zu überwinden, aber mit gutem Willen und eine Auswahl ihrer schönsten Volkstänze. Kriti- der Donaudeutschen Trachtengruppe Speyer, mit Musik und Tanz gestaltete sich der Sams- scher Beobachter dieser Darbietungen war Jos- haben uns mit einem modernen Reisebus auf tagabend zu einem gemütlichen Übungsabend. zef Wenczl, der Schöpfer der Choreographie diese Reise begeben. Wir wollten auch keine Beide Gruppen zeigten was sie können und „Veilchen blaue Augen“. Mit viel Beifall bedach- neue Heimat suchen, sondern wollten sehen, tanzten auch zusammen. Zu dem gelungenen ten die vielen Kirchenbesucher die Darbietungen wo unsere Vorfahren lebten, welche Spuren sie Abend trug sicher auch das im Freien gekochte beider Gruppen. Wie schwierig Kulturpflege ist, hinterlassen haben und wie diese Zeugnisse Kesselgulasch und der Wein aus den Kellern der konnten wir aus den Äußerungen von Frau Groß- heute noch gepflegt werden. Wir wollten Be- Mitglieder bei. In einem Gespräch mit dem Par- habel erkennen, die sich bemüht ein kleines kanntschaften auffrischen, neue Kontakte knüp- lamentsabgeordneten Laszlo Keller konnte über Heimatmuseum zu gestalten und zu erhalten. fen und sehen welche Möglichkeiten es gibt, die Problematik der Minderheiten in Ungarn, so- Am nächsten Tag geht die Fahrt nach Süden. -

Magyar Afrika Társaság African-Hungarian Union

MAGYAR AFRIKA TÁRSASÁG AFRICAN-HUNGARIAN UNION AHU MAGYAR AFRIKA-TUDÁS TÁR AHU HUNGARIAN AFRICA-KNOWLEDGE DATABASE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NINKOV, Olga Eisenhut Ferenc (1857–1903) élete és munkássága / Life and Work of Ferenc Eisenhut (1857–1903) PhD Eredeti közlés /Original publication: 2009, Budapest, ELTE BTK Művészettörténet Tudományi Doktori Iskola, 241 old. Elektronikus újraközlés/Electronic republication: AHU MAGYAR AFRIKA-TUDÁS TÁR – 000.002.734 Dátum/Date: 2018. március / March. filename: NINKOVOlga_2009_EisenhutFerencPhD Az elektronikus újraközlést előkészítette /The electronic republication prepared by: B. WALLNER, Erika és/and BIERNACZKY, Szilárd Hivatkozás erre a dokumentumra/Cite this document NINKOV, Olga: Eisenhut Ferenc (1857–1903) élete és munkássága / Life and Work of Ferenc Eisenhut (1857–1903) PhD, AHU MATT, 2018, 1–242. old., No. 000.002.734, http://afrikatudastar.hu Eredeti forrás megtalálható/The original source is available: Interneten / At the Internet Kulcsszavak/Key words magyar Afrika-kutatás, Eisenhut Ferenc festészeti munkásságában nyomot hagytak észak-afrikai és keleti utazásai African studies in Hungary, Eisenhut Ferenc's paintings have left his mark on North African and Eastern travels -------------------------------------- 2 NINKOV, Olga AZ ELSŐ MAGYAR, SZABAD FELHASZNÁLÁSÚ, ELEKTRONIKUS, ÁGAZATI SZAKMAI KÖNYV-, TANULMÁNY-, CIKK- DOKUMENTUM- és ADAT-TÁR/THE FIRST HUNGARIAN FREE ELECTRONIC SECTORAL PROFESSIONAL DATABASE FOR BOOKS, STUDIES, COMMUNICATIONS, -

0 Planning Report for Twin Cities

Municipal Report Twin Cities - BAČKA PALANKA (Serbia) and ILOK (Croatia) Project is co-funded by the European Union funds (ERDF an IPA II) www.interreg-danube.eu/danurb Municipal Report BAČKA PALANKA (Serbia) Prepared by: Prof. dr Darko Reba, full professor Prof. dr Milica Kostreš, associate professor Prof. dr Milena Krklješ, associate professor Doc. dr Mirjana Sladić, assistant professor Doc. dr Marina Carević Tomić, assistant professor Ranka Medenica, teaching assistant Aleksandra Milinković, teaching assistant Dijana Brkljač, teaching assistant Stefan Škorić, teaching assistant Isidora Kisin, teaching associate Dr Vladimir Dragičević, urban planner DANUrB | Bačka Palanka | Municipal Report 2 CONTENTS 1 HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT 1.1 Bačka Palanka (Serbia) 2 SPACE 2.1 Location and its connection to the Danube 2.2 Bačka Palanka municipality – spatial and socio-economic characteristics 2.3 Accessibility 2.4 Urban structure and land use 2.5 Development potentials 2.6 Mapping and spatial demarcation of data 2.7 Conclusions 3 CULTURAL HERITAGE 3.1 Tangible heritage 3.2 Intangible heritage 3.3 Identifying possibilities for heritage use in regional development 4 TOURISM 4.1 Tourism infrastructure and attractiveness 4.2 Possibilities for touristic network cooperation 5 STAKEHOLDERS’ ANALYSES 5.1 Recognition of stakeholders’ interests 5.2 Possibilities for involvement of stakeholders in DANUrB project 6 DEVELOPMENT POTENTIALS 6.1 National/regional development plans 6.2 Regulatory plans 6.3 Possibilities for joint development plans 7 CONCLUSION DANUrB | Bačka Palanka | Municipal Report 3 1 HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT 1.1 Bačka Palanka (Serbia) Settlement of Bačka Palanka, under this name and with current occupied area, is mentioned fairly late in history. -

Visitor Attraction Case Study Cyclorama Exhibit - Atlanta History Center Atlanta, Ga

VISITOR ATTRACTION CASE STUDY CYCLORAMA EXHIBIT - ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER ATLANTA, GA THE VISIONARIES CHOICE DIGITAL PROJECTION BRINGS THE PAST TO LIFE AT ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER For historians, researching the past and finding ties to the present is a cherished hobby, job, and duty. This is especially important when dealing with one-of-a- kind artifacts from critical moments in history. For the proud city of Atlanta, understanding and experiencing its past is not just for tourism; it is an integral part of the city’s identity and community. So, when the Atlanta History Center sought to create an engaging, larger-than-life experience for their gigantic Cyclorama exhibit, they relied on Digital Projection to tell the story of this precious painting and lead visitors on a journey back through time. Founded in 1926 to preserve and study the history of the city, the Atlanta Historical Society has spent decades collecting, researching, and publishing informa- tion about Atlanta and the surrounding areas. What began as a small, archival-focused group of historians, has now grown into one of the largest local history museums in the country; the Atlanta History Center – hosting exhibitions on the Civil War, Civil Rights Movement, literary masterpieces from Atlanta-born authors, and Native American culture. With four historic houses, 33 acres of curated gardens, and a multitude of wide-ranging programs and displays, it is one of the must-see tourist destinations in Atlanta. One of their key exhibits is the enormous and jaw-dropping Cyclorama. A HISTORIC MOMENT ON A MASSIVE SCALE Originally created in 1886, the 49ft tall by 371ft wide panoramic painting depicts the famous Battle of Atlanta; a critical moment in the Civil War. -

Susan Boardman -- on -- Gettysburg Cyclorama

Susan Boardman -- On -- Gettysburg Cyclorama The Civil War Roundtable of Chicago March 11, 2011, Chicago, Illinois by: Bruce Allardice ―What is a cyclorama?‖ is a frequent question heard in the visitor center at Gettysburg. In 1884, painter Paul Philippoteaux took brush to canvas to create an experience of gigantic proportion. On a 377-foot painting in the round, he recreated Pickett‘s Charge, the peak of fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg. Four versions were painted, two of which are among the last surviving cycloramas in the United States. When it was first displayed, the Gettysburg Cyclorama painting was so emotionally stirring that grown men openly wept. This was state-of- the-art entertainment for its time, likened to a modern IMAX theater. Today, restored to its original glory, the six ton behemoth is on display at the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center. On March 11, Sue Boardman will describe the genre of cycloramas in general and the American paintings in particular: Why they were made, who made them and how. She will then focus on the Gettysburg cycloramas with specific attention to the very first Chicago version and the one currently on display at the Gettysburg National Military Park (made for Boston). Sue Boardman, a Gettysburg Licensed Battlefield Guide since 2000, is a two-time recipient of the Superintendent‘s Award for Excellence in Guiding. Sue is a recognized expert of not only the Battle of Gettysburg but also the National Park‘s early history including the National Cemetery. Beginning in 2004, Sue served as historical consultant for the Gettysburg Foundation for the new museum project as well as for the massive project to conserve and restore the Gettysburg cyclorama. -

November Meeting the Other Cyclorama Sue Boardman Is a Native of Danville, Reservations Are Required Pennsylvania

Newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Atlanta Founded 1949 November 2017 647th Meeting Leon McElveen, Editor November Meeting The Other Cyclorama Sue Boardman is a native of Danville, Reservations Are Required Pennsylvania. She graduated with honors from PLEASE MAIL IN YOUR DINNER Geisinger Medical Center School of Nursing and RESERVATION CHECK OF $36.00 PER Pennsylvania State University. Sue worked as an PERSON TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS: Emergency Room nurse for 23 years. In 2000, she became a Licensed Battlefield Guide and David Floyd received the Superintendent's Award for 4696 Kellogg Drive, SW Excellence in Guiding in 2005 and 2006. In 2002, Lilburn, GA 30047- 4408 Sue joined the Gettysburg Foundation's Museum TO REACH DAVID NO LATER THAN NOON Design Team during the project to build the new ON THE FRIDAY PRECEDING THE MEETING museum and visitor center complex. Reservations and payment may be made Sue served as research historian for the online at: cwrta.org Gettysburg Cyclorama conservation project. She authored the book The Battle of Gettysburg Date: Tuesday, November 14, 2017 Cyclorama: A History and Guide and The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Time: Cocktails: 5:30 pm Civil War on Canvas. Sue has also published the Dinner: 7:00 pm book Elizabeth Thorn: Wartime Caretaker of Place: Capital City Club - Downtown Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery and several 7 John Portman Blvd. articles on the history of the American Civil War cycloramas. Price: $36.00 per person Don’t miss this chance to hear her compare and Program: Sue Boardman contrast two of the world’s great cycloramas, hers and ours. -

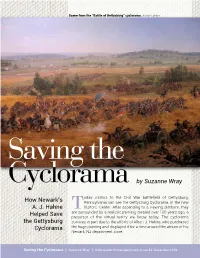

How Newark's A. J. Hahne Helped Save the Gettysburg Cyclorama By

Scene from the "Battle of Gettysburg" cyclorama. Author's photo by Suzanne Wray oday visitors to the Civil War battlefield of Gettysburg, How Newark’s Pennsylvania can see the Gettysburg Cyclorama, in the new A. J. Hahne TVisitors’ Center. After ascending to a viewing platform, they Helped Save are surrounded by a realistic painting created over 100 years ago, a precursor of the virtual reality we know today. The cyclorama the Gettysburg survives in part due to the efforts of Albert J. Hahne, who purchased Cyclorama the huge painting and displayed it for a time around the atrium of his Newark, NJ department store. Saving the Cyclorama | Suzanne Wray | www.GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 42 December 2018 Virtual reality and immersive environments are familiar concepts to most today, but less familiar are their precursors. These include the panorama, also called “cyclorama.” In the nineteenth century, viewers could immerse themselves in another world—a city, a landscape, a battlefield—by entering a purpose-built building, and climbing a spiral staircase to step onto a circular viewing platform. A circular painting, painted to be as realistic as possible, surrounded them. A three-dimensional foreground (the “faux terrain” or “diorama”) disguised the point at which the painting ended and the foreground began. The viewing platform hid the bottom of the painting, and an umbrella-shaped “vellum” hung from the roof, hiding the top of the painting and the skylights that admitted light to the building. Cut off from any reference to the outside world, viewers were immersed in the scene surrounding them, giving the sensation of “being there.”1 An Irish artist, Robert Barker (1739–1806), conceived the circular painting and patented the new art form on June 18, 1787. -

Yadegar Asisi Unveiled His Latest Panorama, TITANIC, on January 28Th, 2017 in the Panometer Leipzig in Germany

# 39 New Panoramas & Restoration Projects Panorama Updates & Related Formats Yadegar Asisi unveiled his latest panorama, TITANIC, on January 28th, 2017 in the Panometer Leipzig in Germany. March 4, 2017 - Panorama Challenge at the Queens Museum in Queens, New York. The Emergence of Pre-Cinema: Print Culture and the Optical Toy of the Literary September 29 - October 2, 2017 - 26th IPC Imagination, a new book by Alberto Gabriele. Conference at the Queens Museum in Queens, New York, USA. More details forthcoming. Hieratic Gaze, a 360 degree visual November 30 - December 2, 2017 - RE:TRACE the experience debuted at the Panorama Music 7th International Conference on the Histories of Media Festival in NYC. This year’s festival will include Art, Science and Technology in Vienna at Danube new works in a 360 dome theater, July 28-30. University. VLC 3.0 media player for Windows and Mac April 28 - 30, 2017 - 10th International Magic now features 360-degree video and photos. Lantern Society Convention in Birmingham, UK GAC Motor’s new GA8 luxury sedan includes a 360-degree visual imaging system. 39 Atlanta Cyclorama by Gordon Jones After years of discussion and intense planning, the time has arrived - the Battle of Atlanta painting is ready for the move from its nearly century-old home in Grant Park to the new custom-built 23,000- square-foot Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building at the Atlanta History Center. The painting is now successfully rolled onto two 45- foot-tall custom-built steel spools – weighing roughly 12,000 pounds each - that are standing inside the Grant Park Cyclorama building awaiting their move.