Archivium Hibernicum Text 2017.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felling 07.07.21.Xlsx

Licences to be advertised 07/07/2021 FL App Ref Date Recieved Scheme DED Townland County Digitised Area (HA) Date Advertised Last date for Submissions CE01-FL0218 29/06/2021 Clearfell BALLYEA DED Derry Clare 10.67 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE01-FL0219 18/06/2021 Clearfell RATH DED Carrowduff, Craggaunboy, Kihaska Clare 14.69 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE01-FL0221 18/06/2021 Clearfell KILFENORA DED,LISDOONVARNA DED,SMITHSTOWN DED Boghil, Fanta Glebe Clare 8.72 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE01-FL0233 18/06/2021 Clearfell ANNAGH DED Shanavogh East, Doonsallagh East Clare 10.69 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE02-FL0242 16/04/2021 Clearfell GLENDREE DED Uggoon Upper Clare 3.45 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE02-FL0244 18/06/2021 Clearfell GLENDREE DED,LOUGHEA DED Maghera, Glendree Clare 11.23 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE02-FL0251 29/06/2021 Clearfell CAHER DED Gortnamearacaun, Scalpnagown Clare 9.03 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE03-FL0214 05/07/2021 Clearfell CAPPAGHABAUN DED Pollagoona Mountain Clare 14.93 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE03-FL0216 05/07/2021 Clearfell CAHERMURPHY DED Slieveanore Clare 1.76 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE03-FL0217 05/07/2021 Clearfell CAHERMURPHY DED Slieveanore Clare 11.54 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE03-FL0228 05/07/2021 Clearfell CAPPAGHABAUN DED Pollagoona Mountain, Loughatorick South Clare 15.7 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE05-FL0116 18/06/2021 Clearfell CAHERHURLEY DED Caherhurly Clare 5.58 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE05-FL0121 27/05/2021 Clearfell LACKAREAGH DED Lackareagh More Clare 14.99 07/07/2021 06/08/2021 CE05-FL0123 18/06/2021 Clearfell CAHERHURLEY DED Caherhurly -

W.I.S.E. Words Index 1999-2015

W.I.S.E. Words Index 1999-2015 f W.I.S.E. Words is the quarterly newsletter published by the W.I.S.E. Family History Society, Denver. Index compiled by Zoe Lappin, 2016 Table of Contents, 1999 edition Names . 1 Places . .2 Topics . 2 Book Reviews and Mentions . 3 Feature Articles . 3 Table of Contents, 2000-2015 editions Names . 5 Places . 25 Topics . 32 Book Reviews and Mentions . 41 Feature Articles . 48 W.I.S.E. Seminars . 50 WISE-fhs.org W.I.S.E. Words Index 1999-2015 W.I.S.E. Words Index 1999-2015 Campbell, Robert Issue 3: 6 1999 Celestine, Pope Issue 2: 6 Charles, Lewis Issue 2: 4 W.I.S.E. Family History Society – Wales, Charles, Mary Issue 2: 4, 5; Issue 4: 4, 5 Ireland, Scotland, England based in Denver, Crown, James Issue 4: 4 Colorado -- began publishing a newsletter in January 1999. Its title was W.I.S.E. Drummond Issue 3: 5 Drummond clan Issue 3: 4 Newsletter and it was a bimonthly publication Drummond, Donald MacGregor Issue 3: 4 of eight pages. Each issue started with page 1 and ended with page 8; there was no Forby, George Issue 1: 4 continuous numbering throughout the year. It lasted one year and in January 2000, the Gregor clan Issue 3: 4 society started over, publishing a quarterly Gregor, King of Picts & Scots Issue 3: 5 with a new format and new name, W.I.S.E. Griffiths, Griffith Issue 4: 4 Words, as it’s been known ever since. -

A Brief History of the Purcells of Ireland

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One: The Purcells as lieutenants and kinsmen of the Butler Family of Ormond – page 4 Part Two: The history of the senior line, the Purcells of Loughmoe, as an illustration of the evolving fortunes of the family over the centuries – page 9 1100s to 1300s – page 9 1400s and 1500s – page 25 1600s and 1700s – page 33 Part Three: An account of several junior lines of the Purcells of Loughmoe – page 43 The Purcells of Fennel and Ballyfoyle – page 44 The Purcells of Foulksrath – page 47 The Purcells of the Garrans – page 49 The Purcells of Conahy – page 50 The final collapse of the Purcells – page 54 APPENDIX I: THE TITLES OF BARON HELD BY THE PURCELLS – page 68 APPENDIX II: CHIEF SEATS OF SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 75 APPENDIX III: COATS OF ARMS OF VARIOUS BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 78 APPENDIX IV: FOUR ANCIENT PEDIGREES OF THE BARONS OF LOUGHMOE – page 82 Revision of 18 May 2020 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND1 Brien Purcell Horan2 Copyright 2020 For centuries, the Purcells in Ireland were principally a military family, although they also played a role in the governmental and ecclesiastical life of that country. Theirs were, with some exceptions, supporting rather than leading roles. In the feudal period, they were knights, not earls. Afterwards, with occasional exceptions such as Major General Patrick Purcell, who died fighting Cromwell,3 they tended to be colonels and captains rather than generals. They served as sheriffs and seneschals rather than Irish viceroys or lords deputy. -

Phases of Irish History

¥St& ;»T»-:.w XI B R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS ROLAND M. SMITH IRISH LITERATURE 941.5 M23p 1920 ^M&ii. t^Ht (ff'Vj 65^-57" : i<-\ * .' <r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library • r m \'m^'^ NOV 16 19 n mR2 51 Y3? MAR 0*1 1992 L161—O-1096 PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY ^.-.i»*i:; PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. so UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Bound in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &> Son, • • « • T 4fl • • • JO Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dttblin First Edition 1919 Second Impression 1920 CONTENTS PACE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and Britain . • • • 3^ . 6i III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian Ireland . • '33 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. • 274 XI. The Norman Conquest * . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 . Index . 357 m- FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. -

Inspector's Report ABP-308829-20

Inspector’s Report ABP-308829-20 Development Permission to construct a dwelling house and garage. Location Moarhaun, Kilnamona, Co Clare. Planning Authority Clare County Council Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 20429 Applicant(s) Cillian Clancy Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Grant with Conditions Type of Appeal Third Party Appellant(s) Antony Travers Observer(s) An Taisce Date of Site Inspection 2nd March 2021 Inspector Mary Crowley ABP-308829-20 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 28 Contents 1.0 Site Location and Description .............................................................................. 4 2.0 Proposed Development ....................................................................................... 4 3.0 Planning Authority Decision ................................................................................. 5 Decision ........................................................................................................ 5 Planning Authority Reports ........................................................................... 6 Prescribed Bodies ......................................................................................... 7 Third Party Observations .............................................................................. 7 4.0 Planning History ................................................................................................... 7 5.0 Policy Context ...................................................................................................... 7 National Planning -

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

Grid Export Data

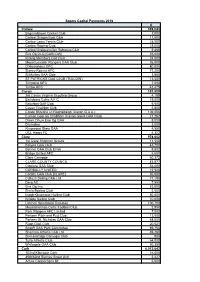

Sports Capital Payments 2018 € Carlow 389,043 Bagenalstown Cricket Club 7,000 Carlow Dragon Boat Club 11,500 Carlow Lawn Tennis Club 28,500 Carlow Rowing Club 18,000 Carlow/Graiguecullen Subaqua Club 9,468 Éire Óg CLG [CARLOW] 35,000 Killerig Members Golf Club 24,500 Mount Leinster Rangers GAA Club 36,000 O'Hanrahans GFC 80,000 Slaney Rovers AFC 71,250 St Mullins GAA Club 3,850 ST PATRICKS GAA CLUB (TULLOW) 13,500 Tinryland GFC 7,000 Tullow RFC 43,475 Cavan 183,809 3rd Cavan Virginia Scouting Group 4,189 Bailieboro Celtic A.F.C 19,000 Belturbet Golf Club 5,500 Cavan Triathlon Club 2,800 Coiste Bhreifne Uí Raghaillaigh (Cavan G.A.A.) 109,686 Cuman Gael an Chabhain (Cavan Gaels GAA Club) 21,262 Droim Dhuin Eire Og GAA 9,000 Drumalee 3,500 Kingscourt Stars GAA 4,550 UCL Harps FC 4,322 Clare 978,602 1st Clare Shannon Scouts 11,500 Ballyea GAA Club 43,700 Banner GAA Club Ennis 9,602 Bridge United AFC 5,500 Clare Camogie 60,372 CLARE COUNTY COUNCIL 83,877 Clonlara GAA Club 54,000 CORBALLY UNITED 12,500 Corofin GAA Club [CLARE] 50,000 Cullaun Sailing Club Ltd 77,180 Derg AC 7,990 Eire Og Inis 53,000 Ennis Boxing Club 2,500 Inagh Kilnamona Hurling Club 50,000 Killaloe Sailing Club 10,000 Lahinch Sportsfield Comittee 100,700 Mountshannon Celtic Football Club 2,850 Park Rangers AFC Limited 7,000 Parteen Pitch and Putt Club 13,500 Parteen St. Nicholas GAA Club 68,000 Ruan GAA Club 20,621 Scariff GAA Park Committee 99,750 Shannon Athletic Club Ltd 39,260 Sixmilebridge Camogie Club 850 Tulla Athletic Club 64,000 Whitegate GAA Club 30,350 Cork 6,013,642 -

Marriage Between the Irish and English of Fifteenth-Century Dublin, Meath, Louth and Kildare

Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires' Booker, S. (2013). Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires'. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, 113, 219-250. https://doi.org/10.3318/PRIAC.2013.113.02 Published in: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2013 Royal Irish Academy. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:25. Sep. 2021 Intermarriage in fifteenth century Ireland: the English and Irish in the ‘four obedient shires’ SPARKY BOOKER* Department of History and Humanities, Trinity College Dublin [Accepted 1 March 2012.] Abstract Many attempts have been made to understand and explain the complicated relationship between the English of Ireland and the Irish in the later middle ages. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 2 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... i Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... ii Biographical Register ........................................................................................................ 1 A .................................................................................................................................... 1 B .................................................................................................................................... 2 C .................................................................................................................................. 18 D .................................................................................................................................. 29 E ................................................................................................................................... 42 F ................................................................................................................................... 43 G ................................................................................................................................. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:01:46Z DP ,Too 0 OO'dtj

Title Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture Author(s) O'Donnell, Katherine Publication date 2000 Original citation O'Donnell, K. 2000. Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b1306492~S0 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2000, Katherine O'Donnell http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1611 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:01:46Z DP ,too 0 OO'DtJ Edmund Burke & the Heritage of Oral Culture Submitted by: Katherine O'Donnell Supervisor: Professor Colbert Kearney External Examiner: Professor Seamus Deane English Department Arts Faculty University College Cork National University of Ireland January 2000 I gcuimhne: Thomas O'Caliaghan of Castletownroche, North Cork & Sean 6 D6naill as Iniskea Theas, Maigh Eo Thuaidh Table of Contents Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" 1 Burke in Nagle Country 13 "Image of a Relation in Blood"- Parliament na mBan &Burke's Jacobite Politics 32 Burke &the School of Irish Oratory 56 Cuirteanna Eigse & Literary Clubs n "I Must Retum to my Indian Vomit" - Caoineadh's Cainte - Lament and Recrimination 90 "Homage of a Nation" - Burke and the Aisling 126 Bibliography 152 Introduction· ''To love the little Platoon" Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) ofpublic affections.