Sometimes the Bear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019938032 Printed on acid-free paper. For our parents, grandparents, and mentors Rev. Dr. Joshua Yoo K. Ahn, PhD and Ruth Soon Hee Ahn (John Ahn) Sarah Lee and Memory of Du Soon Lee (Hannah S. An) Chun Hee Cho and Soon Ja Cho (Paul K.-K. Cho) SooHaeing Kim and Memory of DaeJak Ha (SungAe Ha) Rev. Soon-Young Hong and Hae-Sun Park (Koog-Pyoung Hong) Rev. Seok-Gu Kang and Tae-Soon Kim (Sun-Ah Kang) Rev. Dong Bin Kim and Bong Joo Lee (Hyun Chul Paul Kim) Namkyu Kim and Rev. Dr. Gilsoon Park, PhD (Sehee Kim) Rev. Yong Soon Lim and Sang Nan Yoo (Eunyung Lim) Rev. Dr. Chae-Woon Na, PhD, LittD and Young-Soon Choe (Kang-Yup Na) Kyoung Hee Nam and Soon Young Kang (Roger S. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Trap Pilates POPUP

TRAP PILATES …Everything is Love "The Carters" June 2018 POP UP… Shhh I Do Trap Pilates DeJa- Vu INTR0 Beyonce & JayZ SUMMER Roll Ups….( Pelvic Curl | HipLifts) (Shoulder Bridge | Leg Lifts) The Carters APESHIT On Back..arms above head...lift up lifting right leg up lower slowly then lift left leg..alternating SLOWLY The Carters Into (ROWING) Fingers laced together going Side to Side then arms to ceiling REPEAT BOSS Scissors into Circles The Carters 713 Starting w/ Plank on hands…knee taps then lift booty & then Inhale all the way forward to your tippy toes The Carters exhale booty toward the ceiling….then keep booty up…TWERK shake booty Drunk in Love Lit & Wasted Beyonce & Jayz Crazy in Love Hands behind head...Lift Shoulders extend legs out and back into crunches then to the ceiling into Beyonce & JayZ crunches BLACK EFFECT Double Leg lifts The Carters FRIENDS Plank dips The Carters Top Off U Dance Jay Z, Beyonce, Future, DJ Khalid Upgrade You Squats....($$$MOVES) Beyonce & Jay-Z Legs apart feet plie out back straight squat down and up then pulses then lift and hold then lower lift heel one at a time then into frogy jumps keeping legs wide and touch floor with hands and jump back to top NICE DJ Bow into Legs Plie out Heel Raises The Carters 03'Bonnie & Clyde On all 4 toes (Push Up Prep Position) into Shoulder U Dance Beyonce & JayZ Repeat HEARD ABOUT US On Back then bend knees feet into mat...Hip lifts keeping booty off the mat..into doubles The Cartersl then walk feet ..out out in in.. -

The Aeneid with Rabbits

The Aeneid with Rabbits: Children's Fantasy as Modern Epic by Hannah Parry A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks are owed to Geoff Miles and Harry Ricketts, for their insightful supervision of this thesis. Thanks to Geoff also for his previous supervision of my MA thesis and of the 489 Research Paper which began my academic interest in tracking modern fantasy back to classical epic. He must be thoroughly sick of reading drafts of my writing by now, but has never once showed it, and has always been helpful, enthusiastic and kind. For talking to me about Tolkien, Old English and Old Norse, lending me a whole box of books, and inviting me to spend countless Wednesday evenings at their house with the Norse Reading Group, I would like to thank Christine Franzen and Robert Easting. I'd also like to thank the English department staff and postgraduates of Victoria University of Wellington, for their interest and support throughout, and for being some of the nicest people it has been my privilege to meet. Victoria University of Wellington provided financial support for this thesis through the Victoria University Doctoral Scholarship, for which I am very grateful. For access to letters, notebooks and manuscripts pertaining to Rosemary Sutcliff, Philip Pullman, and C.S. Lewis, I would like to thank the Seven Stories National Centre for Children's Books in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Oxford University. Finally, thanks to my parents, William and Lynette Parry, for fostering my love of books, and to my sister, Sarah Parry, for her patience, intelligence, insight, and many terrific conversations about all things literary and fantastical. -

APRIL Timetable 2018 #SOSEMPOWERS Central YMCA TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD | Mob45 Farringdon | Glasshill Studios SOUTHWARK

APRIL Timetable 2018 #SOSEMPOWERS Central YMCA TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD | Mob45 Farringdon | Glasshill studios SOUTHWARK MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 Pop SWEAT DIVA diva No classes BOSS: Louisa ft 2 chainz Easter Sunday - No Classes All levels All levels BEGINNER All levels Beginner 19.15-20.15 19:00 - 19:45 18.30-19.30 18:30-19.30 13:30-14.30: YES Commercial DE-STRESS HIP POP Commercial Xtina INTERMEDIATE All levels INTERMEDIATE All Levels Beginner 20.00-21.00 19:45 - 20:30 19:30 - 20:30 19:30 - 20:30 14:30 - 16:00: Dirrty SWAG SESSION BArre So Hard All levels All levels 18.30-19.45 12.30-13.15 Commercial: Massari Intermediate 13.30-14.30: Number One Jason Derulo IntermediateALL LEVELS 14.30-16.00: Swalla Vs. Tip toe 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bank holiday SWEAT DIVA diva No classes BOSS: Amerie COMMERCIAL No classes All levels BEGINNER All levels BeGINNER All levels 19:00 - 19:45 18.30-19.30 18:30-19.30 13.30 - 14.30: One thing 14.00-14.45 DE-STRESS HIP POP Commercial BEYONCÉ SASS SESSION SOS SOUl Sessions: Whitney Houston All levels INTERMEDIATE All Levels All levels Intermediate 19:45 - 20:30 19:30 - 20:30 19:30 - 20:30 14.30-16.00: Partition 15.00-16.30: I’m Every woman SWAG SESSION BArre So Hard All levels All levels 18.30-19.45 12.30-13.15 Commercial: Cardi B ALLIntermediate LEVELS 13.30-14.30: Bodak Yellow vs. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Top-Up Experience at SPEAR3 Contents

Top-Up Experience at SPEAR3 Contents • SPEAR 3 and the injector • Top-up requirements • Hardware systems and modifications • Safety systems & injected beam tracking • Interlocks & Diagnostics SPEAR3 Accelerator Complex NEXAFS XAFS PX PX PX PD/XAS SAXS/PX XAS/TXM 3GeV 10nm-rad 500 mA BTS ARPES 5W, 1.6nA 10Hz Single bunch/pulse Coherent Environment XAS Booster LINAC/RF Gun 3GeV Injector E (White Circuit) N S W Top ‘off’ at SPEAR3 o Rebuild SPEAR into SPEAR3 (1999-2003) o Operated at 100mA for ~6 years (beam line optics) o Recently increased to 200mA o Chamber components get hot at 500ma (450kW SR, impedance) o 500mA program suspended because of power load transient on beam line optics o Instead worked to top-off mode (beam decay mode, fill-on-fill) RF system and vacuum chamber rated for 500ma Present Status o 13 exit ports taking SR (9 Insertion Device, 4 Dipole) o 7 ID ports presently in „fill-on-fill‟ open shutter mode o 4 dipole beam lines open shutter injection by end of October 2009 o Last two ID shutters fill-on-fill by June 2010 o Trickle charge 2011 100mA and 500mA Operation SPEAR 3 100 vs. 500 mA Fill Scenarios lifetime = 14 h @ 500 mA ~6.5 Amp-hr = 60 h @ 100 mA 500 450 500ma 400 =180ma 350 300 250 200 current (mA) current 150 100ma 100 50 =12ma 0 0 4 8 12 16 20 24 time (hrs) 500mA Injection Scenarios delivery time = 8 hr delivery time = 2 hr tfill = ~6-7 min tfill = ~1.5-2 min SPEAR 3 500 mA Fill Scenario SPEAR 3 500 mA Fill Scenario lifetime = 14 h @ 500 mA lifetime = 14 h @ 500 mA 500 500 450 450 400 400 350 350 300 300 delivery -

Tribute Bands Top Off Summer Music Series Tickets on Sale for Love

Weather and Tides FREE page 21 Take Me Home VOL. 19, NO. 33 From the Beaches to the River District downtown Fort Myers AUGUST 14, 2020 Tribute Bands Top Off Summer Music Series wo tribute bands will recreate the British invasion during the Sounds of TSummer series finale at the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center on Friday and Saturday, August 21 and 22. The Nowhere Band will perform on Friday, while zSTONEz will be in concert on Saturday. Doors open at 7 p.m. with performances at 7:30 p.m. Due to CDC guidelines, seating is strictly limited and masks are strongly recommended. The Nowhere Band is Southwest Florida’s premier Beatles tribute band, zSTONEz covering the full spectrum of The Beatles’ Tuesday, Wild Horses and Jumpin’ Jack long and varied career. They create an Flash. unparalleled reproduction, entirely live (with Tickets are $22 and available at the box no pre-recorded material), of ‘60s Beatles office, by phone at 333-1933 or the day performances. The band blends period of show at the door. costumes, authentic instruments, modern The Nowhere Band photos provided The Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center lighting and a talented quartet of musicians to miss. For more information, visit www. Rolling Stones tribute band. They will is located at 2301 First Street in downtown to create an experience any true Beatles thenowhereband.com. perform legendary rock and roll hits like Fort Myers. For more information, visit fan, young or young at heart, can’t afford The group zSTONEz is the leading (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, Ruby www.sbdac.com or call 333-1933. -

2021 Chevrolet Tahoe / Suburban 1500 Owner's Manual

21_CHEV_TahoeSuburban_COV_en_US_84266975B_2020AUG24.pdf 1 7/16/2020 11:09:15 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 84266975 B Cadillac Escalade Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada/Mexico- 13690472) - 2021 - Insert - 5/10/21 Insert to the 2021 Cadillac Escalade, Chevrolet Tahoe/Suburban, GMC Yukon/Yukon XL/Denali, Chevrolet Silverado 1500, and GMC Sierra/Sierra Denali 1500 Owner’s Manuals This information replaces the information Auto Stops may not occur and/or Auto under “Stop/Start System” found in the { Warning Starts may occur because: Driving and Operating Section of the owner’s The automatic engine Stop/Start feature . The climate control settings require the manual. causes the engine to shut off while the engine to be running to cool or heat the Some vehicles built on or after 6/7/2021 are vehicle is still on. Do not exit the vehicle vehicle interior. not equipped with the Stop/Start System, before shifting to P (Park). The vehicle . The vehicle battery charge is low. see your dealer for details on a specific may restart and move unexpectedly. The vehicle battery has recently been vehicle. Always shift to P (Park), and then turn disconnected. the ignition off before exiting the vehicle. Stop/Start System . Minimum vehicle speed has not been reached since the last Auto Stop. If equipped, the Stop/Start system will shut Auto Engine Stop/Start . The accelerator pedal is pressed. off the engine to help conserve fuel. It has When the brakes are applied and the vehicle . The engine or transmission is not at the components designed for the increased is at a complete stop, the engine may turn number of starts. -

Michigan Irish Music Festival Returns to Top Off Summer. Page 10

Michigan Irish Music Festival Returns to Top Off Summer. Page 10. AUGUST | SEPTEMBER 2017 A MESSAGE FROM THE PUBLISHER Welcome to the August – September issue of PLUS. I hope your summer is going well! It won’t be too much longer and the kids will be going back to n n school. We’ll be slowing down a little and getting ready for our Fall routines. 3 LEGALEASE • 9 LAKESHORE I’m just guessing but I’ll bet some WHY YOU NEED A FAMILY • of you are eagerly awaiting the WILL IN ADDITION TO SUPPORTING YOUR return to your favorite TV series. A REVOCABLE LIVING STUDENT BACK- Getting a little tired of reruns and the lack of fresh TV entertainment. TRUST TO-SCHOOL Personally I’m not much of a TV Jonathan J. David Heather Artushin viewer. I do like to watch the local and national news while making 4 n GOOD SPORTS • 10 n THE THREE dinner but after that I’d rather watch a movie or some offering TURNING BIG REDS STAGES OF FUN - on Netfl ix. Just recently I had the INTO LEADERS OFF MICHIGAN IRISH opportunity to purchase my all- THE FIELD MUSIC FESTIVAL time favorite TV sitcom. The sitcom Tom Kendra Marla Miller I’m referring to debuted in 1975 and ran for eight straight seasons. Back in the 80’s I worked as the n n 5 HOME SWEET 12 GOOD FOOD manager of the Grand Theatre in HOME • MARKET UP • BOUNTY OF THE Grand Haven. I would race home every night so I could be home by 11:30 pm, OR MARKET DOWN? SEASON turn the TV to WZZM and tune in to what I think is the best TV show of my generation…Barney Miller. -

The Meadow 2015 Literary and Art Journal

MEADOW the 2015 TRUCKEE MEADOWS COMMUNITY COLLEGE Reno, Nevada The Meadow is the annual literary arts journal published every spring by Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno, Nevada. Students interested in the creative writing and small press publishing are encour- aged to participate on the editorial board. Visit www.tmcc.edu/meadow for information and submission guidelines or contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected] or through the English department at (775) 673- 7092. The Meadow is not interested in acquiring rights to contributors’ works. All rights revert to the author or artist upon publication, and we expect The Meadow to be acknowledged as original publisher in any future chapbooks or books. The Meadow is indexed in The International Directory of Little Magazines and Small Presses. Our address is Editor-in-Chief, The Meadow, Truckee Meadows Commu- nity College, English Department, Vista B300, 7000 Dandini Blvd., Reno, Nevada 89512. The views expressed in The Meadow are solely reflective of the authors’ perspectives. TMCC takes no responsibility for the creative expression contained herein. The Meadow Poetry Award: Sara Seelmeyer The Meadow Fiction Award: Joan Presley The Meadow Nonfiction Award: Zachary Campbell Cover art: Laura DeAngelis www.lauralaniphoto.com Novella Contest Judge: Brandon Hobson www.tmcc.edu/meadow ISSN: 1947-7473 Editors Lindsay Wilson Eric Neuenfeldt Prose Editor Eric Neuenfeldt Poetry Editor Lindsay Wilson Editorial Board Todd Ballowe Erika Bein Harrison Billian Zachary Campbell Jeff Griffin Diane Hinkley Molly Lingenfelter Angela Lujan Kyle Mayorga Xan McEwen Vincent Moran Joan Presley Henry Sosnowski Caitlin Thomas Peter Zikos Proofreader Zachary Campbell Cover Art Laura DeAngelis Table of Contents Nonfiction Zachary Campbell A Drunk and a Shepherd 53 Fiction Toni Graham FUBAR 14 Dave Andersen Settlement 42 Joan Presley Circus 72 Orville Williams Too Beautiful for This Place 85 The 2015 Novella Prize Jerry D. -

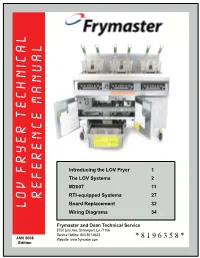

LOV FRYER TECHNICAL REFERENCE MANUAL Website: Service Hotline:800-551-8633 8700 Line Ave, Shreveport, LA 71106 Frymaster Anddean Technical Service

Introducing the LOV Fryer 1 The LOV Systems 2 M2007 11 RTI-equipped Systems 27 REFERENCE MANUAL Board Replacement 32 LOV FRYER TECHNICAL Wiring Diagrams 34 Frymaster and Dean Technical Service 8700 Line Ave, Shreveport, LA 71106 Service Hotline: 800-551-8633 JAN 2008 Website: www.frymaster.com Edition *8196358* LOV Technical Reference M2007 Computer Filter Light Replace JIB Light Diagnostic LED Screen Reset button JIB (behind right door) The LOV fryer Introducing the Low Oil Volume Fryer The Low Oil Volume (LOV) fryer is a McDonald’s-only, feature-laden version of the RE fryer introduced in 2006. The enhancements found on the LOV fryer include: • Low volume frypot —30 pounds (5 liters) rather than 50 pounds (25 liters) of oil. • Automatic top-off — the fryer automatically maintains an optimal oil level with a reservoir in the cabinet. • M2007 computer — a sophisticated controller with multiple levels of programming. • Automatic filtration — the fryer performs hands-free filtering at prescribed cook cycle counts or at prescribed times. • Oil savings — The combination of a low-volume fry vat and oil automatically kept at a optimal level, reducing oil usage. A similar fryer, the Protector, is available for the general market. It has the LOV’s auto top-off feature and the on-board oil reservoir, the smaller fry vat and the oil savings associated with smaller vat and the top-off feature. Filtering using the CM7 computer on a Protector fryer is manual. The Protector Fryer LOV Technical Reference LOW Oil RTD Oil top off port High limit Auto Filtra- tion RTD The solenoid tree and the pump, which move oil from the reservoir to the frypots, are visible above.