Report to the General Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linked: Breathing & Postural Control

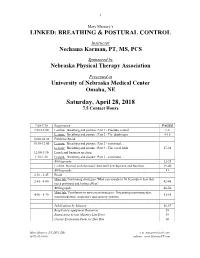

i Mary Massery’s LINKED: BREATHING & POSTURAL CONTROL Instructor Nechama Karman, PT, MS, PCS Sponsored by Nebraska Physical Therapy Association Presented at University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE Saturday, April 28, 2018 7.5 Contact Hours 7:00-7:30 Registration PAGES 7:30-10:00 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 1 - Pressure control 1-8 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 2 - The diaphragm 9-16 10:00-10:30 Exhibitor Break 10:30-12:00 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 2 - continued… Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 3 - The vocal folds 17-21 12:00-1:30 Lunch and business meeting 1:30-2:30 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 3 - continued… Bibliography 22-28 Lecture: Normal and abnormal chest wall development and function 29-40 Bibliography 41 2:30 - 2:45 Break Mini-lab: Positioning strategies: What can you do in 90 Seconds or less that 2:45 - 4:00 42-45 has a profound and lasting effect? Bibliography 46-50 Mini-lab: Ventilatory or movement strategies: Integrating neuromuscular, 4:00 - 5:30 51-55 musculoskeletal, respiratory and sensory systems Publications by Massery 56-57 Respiratory equipment Resources 58 Instructions to join Massery List Serve 59 Course Evaluation Form for Day One 60 Mary Massery, PT, DPT, DSc e-m: [email protected] (847) 803-0803 website: www.MasseryPT.com ii COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will challenge the practitioner to make a paradigm shift: connecting breathing mechanics and postural control with management of trunk pressures. Through Dr. Massery’s model of postural control (Soda Pop Can Model), the speaker will link breathing mechanics with motor and physiologic behaviors (a multi-system perspective). -

Posture Alignment and the Surrounding Musculature An

Posture Alignment and the Surrounding Musculature An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Brittany Moffett Thesis Advisor Mary Winfrey-Kovell Ball State University Muncie, Indiana November 2019 Expected Date of Graduation December 2019 Abstract It is reported that musculoskeletal conditions are the most common reason to seek medical consultations in the U.S., therefore, it is important to find the underlying cause of the pain and discomfort that society is experiencing (Osar, 2012). When examining the musculoskeletal system and how it is interconnected with the nervous system, it can be found that society as a whole experiences dysfunction from simple everyday movement patterns that can lead to injury and pain (Page, 2014). One’s posture is critical to health and wellness, and activities of daily living as the core and the spine are crucial in determining how the rest of the body moves and functions. The position of the spine is determined by the neuromuscular system surrounding the spine and along the kinetic chain which affects an individual’s movement patterns. Evidence indicates any small deviation along the kinetic chain will result in change to the neuromuscular system and the increased risk of injury or pain. Because posture and the risk of injury or pain are correlated, it is critical to be able to differentiate between good posture and the different types of posture deviations. The purpose of this paper is to define good posture and provide an understanding of the underlying causes of postural deviations. An analysis of the four types of postural deviations – lordosis, kyphosis, flat back, and sway back will provide the ability to recognize the common types of postural deviations and provide a structured approach to correcting each type of postural deviation. -

Treatment of the Sportsman's Groin' British Hernia Society Position

Consensus statement Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092872 on 22 October 2013. Downloaded from ‘Treatment of the Sportsman’s groin’: British Hernia Society’s 2014 position statement based on the Manchester Consensus Conference Aali J Sheen,1 B M Stephenson,2 D M Lloyd,3 P Robinson,4 D Fevre,5 H Paajanen,6 A de Beaux,7 A Kingsnorth,8 O J Gilmore,9 D Bennett,10 I Maclennan,1 PO’Dwyer,11 D Sanders,8 M Kurzer12 For numbered affiliations see ABSTRACT groin.6 Chronic groin pain is most often found in end of article. Introduction The aim was to produce a athletes who undertake sports involving kicking 7 Correspondence to multidisciplinary consensus to determine the current and twisting movements while running. The pain Aali J Sheen, Honorary Senior position on the nomenclature, definition, diagnosis, is often experienced at the common point of origin Lecturer, University of imaging modalities and management of Sportsman’s of the rectus abdominis muscle and the adductor Manchester and Consultant groin (SG). longus tendon on the pubic bone and the insertion Surgeon, Department of Methods Experts in the diagnosis and management of of the inguinal ligament on the pubic bone.5 Surgery, Central Manchester Foundation Trust, Manchester SG were invited to participate in a consensus conference Furthermore, it is important to remember that Royal Infirmary, Manchester held by the British Hernia Society in Manchester, UK on there is to date no clear consensus as to what spe- M13 9WL, UK; 11–12 October 2012. Experts included a physiotherapist, cifically constitutes this diagnosis8 and in addition [email protected] a musculoskeletal radiologist and surgeons with a proven it has been recognised that treatment relies on both track record of expertise in this field. -

Posture Types – Part 3

Posture types – Part 3 Flat-back posture Flat-back posture is the lack of mobility and flattening of the lumbar spine. The features are as follows: Head is forward Cervical spine is slightly extended The rectus abdominis and external obliques (EO) are tight and become the most dominant of the abdominal muscles The hamstrings are tight The one-joint hip flexors are found to be long and weak The pelvis is posteriorly tilted Back erectors are slightly stretched Knees are slightly flexed Flat-back posture is common in: People who tend to perform lots of ‘sit-up’ type of exercises Boxers People with poor core and back stability and who have had long periods of inactivity Guidelines for the correction of flat-back posture: Regain mobility in the lumbar spine Use strengthening exercises for the lower back Stretch the hamstrings Strengthen/shorten the hip flexors Stretch the rectus abdominis – ideally over a stability ball Suitable Pilates exercises: Pelvic tilts, Shoulder bridge, rolling back Swan dive, swimming, spine twist Half and full Roll up, chest opener Focus on set up position and realigning cervical spine Focus on stretching hamstrings Sway-back posture Posture features are as follows: Head/chin is held forward Cervical spine is slightly extended; neck flexors are weak Thoracic spine has increased flexion (kyphotic); thoracic extensors are weak Lumbar spine is flexed (flat lower back) Posterior tilted pelvis – pelvis is swayed forward in relation to the feet Hip flexors are long and weak Obliques (upper fibres) -

Bachelor of Science in Athletic Training Student Handbook 2018-2019 Academic Year

Bachelor of Science in Athletic Training Student Handbook 2018-2019 Academic Year Policies in this handbook are for all Pre-Athletic Training, and Athletic Training Majors In addition to this handbook, students are to refer to the College of Health and Human Services Student Handbook and the UNC Charlotte Undergraduate Catalog Table of Contents UNC Charlotte’s Athletic Training Education Program 4 Vision Statement 4 Mission Statement 4 Program Goals and Objectives 5 Accreditation Status 20 Faculty Information 21 Introduction to Athletic Training 22 The Athletic Training Profession 22 Regulation of Athletic Training 22 Essential Functions of an Athletic Trainer 23 UNC Charlotte’s Athletic Training Education Program Curriculum 24 Prerequisite Requirements 24 Course Sequence – Upper Division Athletic Training Major 25 Suggested 4 – year Course Sequence 26 Course Descriptions 28 Athletic Training Education Program Clinical Coursework 30 Athletic Training Education Program Clinical Education Faculty 32 Athletic Training Education Program Affiliated Clinical Sites 33 Athletic Training Program Student Policies and Procedures 34 Academic Advising 34 Athletic Training Education Program General Admission Requirements 35 Athletic Training Education Program Application Requirements 36 Athletic Training Education Program Procedures for Admission 37 Athletic Training Education Program Required Costs 38 Athletic Training Education Program Progression and Retention Policy 39 Bachelor of Science in Athletic Training Degree Graduation 41 Requirements Athletic -

The Anatomical “Core”: a Definition and Functional Classification

Osteopathic Family Physician (2011) 3, 239-245 The anatomical “core”: a definition and functional classification John J. Dougherty, DO, FACOFP, FAOASM From the Department of Family Medicine, Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences, Kansas City, MO. KEYWORDS: The anatomic core is important in the functional stabilization of the body during static and dynamic Core; movement. This functional stabilization is an integral component of proprioception, balance perfor- Static function; mance, and compensatory postural activation of the trunk muscles. The structures that define the core Dynamic function; and its functions are presented here. By understanding the contributing components and responsibilities Sensory-motor control of the core, it is hoped that the physician will have a better understanding of core function as it relates to the performance of their patients’ activities of daily living. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Core training has found its way into the lexicon of functional unit, synergistically adjusting the entire body to countless exercise regimens. However, clinically there has maintain balance, postural stabilization, and mobility. These been little comprehensive definition and even less practical abilities are essential in the performance of basic activities characterization of this “core.” The word core derives from of daily living (ADLs).7 the Greek word kormos, which loosely translates to “trunk Neurologic and musculoskeletal impairments can alter of a tree.” An additional word origin comes from the Span- these normal biomechanical relationships.8-10 Such impair- ish word for heart, corazon. George Lucas selected “Cora- ment effects a functional shift of the structural burden to the zon” as the name for the planet at the center of his “Star components of the core.1 The resultant alterations impose Wars” universe. -

The Care of Your Back

Page 1 of 36 MC1677 The Care of Your Back The Care of Your Back p a t i e n t e d u c a t i o n Page 2 of 36 MC1677 The Care of Your Back Page 3 of 36 MC1677 The Care of Your Back Introduction Back pain affects people of all ages, sex, and socioeconomic status. Statistics show that four out of every five adults (80 percent) have or will experience back pain. The good news is that back pain is usually not due to any serious disease or injury of your back. The causes of back pain are many and may include any of the following: • Poor posture • Improper body mechanics • Muscle strain • Ligament sprain • Muscle weakness • Life style choices such as smoking, excessive body weight, diminished physical fitness or excessive physical or mental stress • Joint and disk disease This booklet contains information that will help you protect your back against injury while engaging in activities of daily living. It contains information about the causes of low back pain, posture, proper body mechanics, exercise and energy-saving techniques. 1 Page 4 of 36 MC1677 The Care of Your Back Dealing with Back Pain If you experience back pain, keep the following facts in mind: • Most people with back pain do not have any significant damage in their spine. • Back pain is usually not due to any serious disease. • Most back pain is temporary and lasts only a short while. • If you regularly experience back pain, you may have good days and bad days with regard to your pain. -

A-Dec Dental Professional Use of Ergonomically Designed Seating

WHITE PAPER Dental Professional Use of Ergonomically Designed Seating 2 A-DEC WHITE PAPER DENTAL PROFESSIONAL USE OF ERGONOMICALLY DESIGNED SEATING TABLE OF CONTENTS History of Dental Seating ..................................................................................... 3 Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Dental Health Professionals ...................... 3 Prevalence ............................................................................................................. 3 Pertinent Anatomy and Definitions ...................................................................... 4 The Vertebral Column ........................................................................................... 4 Muscles of the Trunk ............................................................................................ 4 Neutral Spine ........................................................................................................ 4 Spinal Motions and Positions .............................................................................. 5 Benefits of a ‘Neutral Spine’ ................................................................................ 5 Lumbar Spine Structures ..................................................................................... 5 Muscles of the Lumbar Spine and Trunk ............................................................ 6 Posture of the Cervical and Thoracic Spine ........................................................ 6 Dynamic Sitting .................................................................................................... -

A Conceptual Back Injury Prevention Program for Volleyball Athletes

[ CLINICAL COMMENTARY ] CHAD E. SMITH¹@E>DDOB7D:"DPT, EdD, SCS, ATC, CSCS, FACSM²F7KB97K:?BB¹ @EI;F>8HEIAO"PT, MS, SCS3:7L?:D$C$978EHD"MD4 Dynamic Trunk Stabilization: A Conceptual Back Injury Prevention Program for Volleyball Athletes igh spinal forces during the sport of volleyball make it essential the ankle and upper leg (J78B; ').1 Low to have well-developed trunk muscle function.120 Back and back injury risk increases with spinal shoulder injuries are common to volleyball and can primarily twisting, lateral bending, and asymmetri- cal movements.3,48 be attributed to the stresses of frequent spiking and jump H The “trunk” refers to the body region serving, both activities characterized by simultaneous forceful spinal excluding the head, neck, and extremi- hyperextension and rotation, in addition to extreme shoulder external ties. The most important trunk muscle rotation (<?=KH;').15 Most acute volleyball injuries occur at the ankle function is to provide dynamic stabil- ity.83 Instability is the inability to prop- (23%) and knee (17%); however, the tion injury surveillance data for women’s erly maintain postural alignment, while back (16%) is the third most injured volleyball injuries, Agel et al1 reported stability is the capacity to resist change region.12 Most chronic volleyball that the low back ranked fourth and maintain or resume an original posi- injuries occur at the knee (33%) among body regions injured dur- tion following displacement.125 Dynamic and shoulder (20%), while the SUPPLEMENTAL ing games, following the ankle, trunk stability is the capacity to control VIDEOS ONLINE back (18%) is the next most in- knee, and shoulder. -

Physiotherapy Scoliosis-Specific Exercises – a Comprehensive Review of Seven Major Schools

Berdishevsky et al. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders (2016) 11:20 DOI 10.1186/s13013-016-0076-9 REVIEW Open Access Physiotherapy scoliosis-specific exercises – a comprehensive review of seven major schools Hagit Berdishevsky1*† , Victoria Ashley Lebel2†, Josette Bettany-Saltikov3, Manuel Rigo4, Andrea Lebel5, Axel Hennes6, Michele Romano7,8, Marianna Białek9, Andrzej M’hango9, Tony Betts10, Jean Claude de Mauroy11 and Jacek Durmala12 Abstract In recent decades, there has been a call for change among all stakeholders involved in scoliosis management. Parents of children with scoliosis have complained about the so-called “wait and see” approach that far too many doctors use when evaluating children’s scoliosis curves between 10° and 25°. Observation, Physiotherapy Scoliosis Specific Exercises (PSSE) and bracing for idiopathic scoliosis during growth are all therapeutic interventions accepted by the 2011 International Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment (SOSORT). The standard features of these interventions are: 1) 3-dimension self-correction; 2) Training activities of daily living (ADL); and 3) Stabilization of the corrected posture. PSSE is part of a scoliosis care model that includes scoliosis specific education, scoliosis specific physical therapy exercises, observation or surveillance, psychological support and intervention, bracing and surgery. The model is oriented to the patient. Diagnosis and patient evaluation is essential in this model looking at a patient-oriented decision according to clinical experience, scientific evidence and patient’s preference. Thus, specific exercises are not considered as an alternative to bracing or surgery but as a therapeutic intervention, which can be used alone or in combination with bracing or surgery according to individual indication. -

Finite Element Study of Sitting Con Gurations to Reduce Sacroiliac Joint

ORIG I NAL RE SEARCH McGill Journal of Medicine Finite element study of sitting configurations to reduce sacroiliac joint loads Isabella Bozzo1 | Brandon Malz1 1McGill University, Montreal, Canada ABSTRACT Correspondence Low back pain can be caused by prolonged sitting, originating in the Isabella Bozzo sacroiliac joint (SIJ) in up to 30% of patients. The goal of this study was to Email: [email protected] develop a finite element model of the lower back and pelvis to study sit- Publication Date ting configurations that could minimize the loads in the SIJ while sitting. September 27, 2020 The configurations were based on chair designs with geometries known MJM 2020 (18) 20 to show some benefits according to literature: a 5◦ downward seat pan tilt and a 20◦ backrest recline. Both chairs were evaluated in neutral spine position with upright posture and 30◦ forward leaning configurations. A finite element model of the lumbar spine, pelvis and femurs was devel- www.mjmmed.com oped to compute the reaction forces at the SIJ. The intricate spinal ge- ometry was simplified, and isotropic material properties were assumed This work is licensed under a Creative for all components. The chair reaction forces were first computed analyt- Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International ically, then inputted as loads on the model. The results demonstrate that License. the improved sitting configuration reduced the loads in the SIJ compared to a conventional chair in both upright and forward leaning positions by 5.57% body weight (BW) and 14.18%BW, respectively. The proposed sit- ting configuration with a downward inclined seat pan and forward leaning back was shown to be an effective method to reduce SIJ loads. -

Neutral Pain-Free Spine Position

Neutral Pain-Free Spine Position Ancillary to any of the exercises discussed in the BASE protocol is an understanding of the “Neutral Pain-Free Spine Position.” The Neutral Pain-Free Spine Position is the foundation for trunk stabilization. A neutral spine is a posture that demonstrates the three natural curves that are found in a healthy spine. (Figure 1) A pain- free spine is a posture where pain is not present in the spine. Therefore, a Neutral Pain-Free Spine Position would be a posture that demonstrates the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar curvature of the spine (to the best of your ability) while not actively causing any pain. This posture is not only necessary for the practice of each of the exercises utilized in the BASE protocol, but also for everyday life. The purpose of maintaining good spine posture is to improve “spinal proprioception.” Basically, this is being aware of your spine as it relates to the rest of your body. Just as you have an awareness of your arms as you move them around your body, so too should you have an awareness of your spine and Figure 1 back muscles as they support your trunk in everyday activities. Becoming mindful of your spine posture and maintaining a neutral, pain free position should be an intense area of focus as you begin your recovery. Improved spinal proprioception is associated with decreased back pain. With patience and discipline you will eventually maintain good spinal posture automatically. The primary muscles involved in maintaining a pain-free neutral spine are the multifidi, which is a muscle that spans down the entire length of the spine on both sides of the vertebrae.