Waste: Background Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formal Report

Issue Date: December 2008 UNCLASSIFIED Issue No: 2 DIRECTORATE MAJOR PROJECT 7. Ground Conditions Mensa Environmental Appraisal Volume 1 7. GROUND CONDITIONS 4) Landscaping and biodiversity proposals, details can be found within 7.2.2 National Planning Policy Chapter 13: Landscape and Visual Impacts. 7.2.2.1 Planning Policy Statement (PPS) 23: Planning and Pollution 7.1 Introduction It is proposed that the Application Site will be surrounded with a security fence to Control separate the construction works from the rest of AWE Burghfield. This fence line This chapter describes the geological, hydrological, hydrogeological, and will traverse the eastern most extent of the Former Site Tip, located in the north Land contamination and its risk to health is a material consideration under potential land contamination aspects of the Application Site. eastern reaches of AWE Burghfield (see Figure 7-1). planning and development control, and applies to the intended use of the site. Existing guidance on assessing risks to health under the Town and Country An assessment has been undertaken to ascertain whether, and to what extent, 7.2 Legislation and Planning Policy Context Planning Acts is limited to the amended Planning Policy Statement (PPS) 23: the Proposed Development and the environment will be impacted by the current ‘Planning and Pollution Control’ (Ref. 7-6), which more clearly aligns the ground conditions within the Application Site. This will include the assessment of Re-development of brownfield land must take into account the regulatory context requirements under planning with those under Part IIA. This is consistent with the potential radiological, explosive and chemical ground contamination from either of the proposal site and development, provide information that is fit for purpose practical requirements that a site under planning for its intended or proposed use current or historical uses of the Application Site. -

Maps Covering Berkshire HYDROCARBONS 00 450 500

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 905 00 000 10 20 2 000 2 000 00 CHALK BRICK CLAY BGS maps covering Berkshire HYDROCARBONS 00 450 500 The term ‘brick clay' is used to describe clay used predominantly in the manufacture of bricks and, to a lesser extent, roof tiles and clay Chalk is a relatively soft, fine-grained, white limestone, consisting mostly of the debris of planktonic algae. In Berkshire, chalk crops out 268 Conventional Oil and Gas across a third of the county, particularly in the west and northeast where it forms the prominent natural feature of the Chalk Downlands. pipes. These clays may sometimes be used in cement manufacture, as a source of construction fill and for lining and sealing landfill Report 12 1:63 360 and 1:50 000 map published Approximately two thirds of the chalk outcrop in Berkshire lies within the North Wessex Downs AONB. The Chalk is divided into the sites. The suitability of a clay for the manufacture of bricks depends principally on its behaviour during shaping, drying and firing. This 253 254 255 The county of Berkshire occupies a large tract of land to the north of a prominent line of en echelon anticlinal structures across southern Grey Chalk (formerly the Lower Chalk) and White Chalk (formerly the Middle and Upper Chalk) Subgroups. The White Chalk subgroup is will dictate the properties of the fired brick such as strength and frost resistance and, importantly, its architectural appearance. Britain. These folds mark the northern limits of the Palaeogene (Alpine) inversion of the main faults that controlled the development of the the most extensive with the underlying Grey Chalk Subgroup only cropping out as narrow bands at Walbury Hill and Lambourn, in the Report 64 Report 32 Report 42 Report 12 1:25 000 map published (Industrial west of the county and at Streatley in the north of the county. -

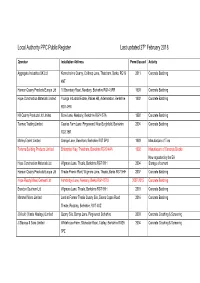

WB PPC Public Register

th Local Authority PPC Public Register Last updated 27 February 2018 Operator Installation Address Permit Issued Activity Aggregate Industries UK Ltd Kennetholme Quarry, Colthrop Lane, Thatcham, Berks, RG19 2011 Concrete Batching 4NT Hanson Quarry Products Europe Ltd 10 Boundary Road, Newbury, Berkshire RG14 5RR 1993 Concrete Batching Hope Construction Materials Limited Youngs Industrial Estate, Paices Hill, Aldermaston, Berkshire 1992 Concrete Batching RG7 4PW Hill Quarry Products Ltd Limited Bone Lane, Newbury, Berkshire RG14 5TA 1992 Concrete Batching Tarmac Trading Limited Cearles Farm Lane, Pingewood, Near Burghfield, Berkshire 2004 Concrete Batching RG3 3BR Marley Eternit Limited Grange Lane, Beenham, Berkshire RG7 5PU 1993 Manufacture of Tiles Forterra Building Products Limited Enterprise Way, Thatcham, Berkshire RG19 4AN 1992 Manufacture of Concrete Blocks Now regulated by the EA Hope Construction Materials Ltd Wigmore Lane, Theale, Berkshire RG7 5HH 2004 Storage of cement Hanson Quarry Products Europe Ltd Theale Premix Plant, Wigmore Lane, Theale, Berks RG7 5HH 2007 Concrete Batching Hope Ready Mixed Cement Ltd Hambridge Lane, Newbury, Berks RG14 5TU 2007-2015 Concrete Batching Breedon Southern Ltd Wigmore Lane, Theale, Berkshire RG7 5HH 2015 Concrete Batching Marshall Mono Limited Land at Former Theale Quarry Site, Deans Copse Road 2016 Concrete Batching Theale, Reading, Berkshire, RG7 4GZ J.Mould (Waste Haulage) Limited Quarry Site, Berrys Lane, Pingewood Berkshire 2003 Concrete Crushing & Screening J.Staceys & Sons Limited -

Late Bronze Age & Iron Age Berkshire

SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK LATER BRONZE AGE AND IRON AGE BERKSHIRE Steve Ford October 2007 Inheritance The subdivision of prehistory into periods has long been recognised as a mechanism for description of what is essentially a continuum of development. Yet some of the subdivisions are of much more significance than others, for example the introduction of agriculture. For the period under consideration here it is not therefore that the widespread adoption of iron which is necessary significant but perhaps the transition from ‘monument dominated landscapes and mobile settlement patterns to that of more permanent settlement and a greater emphasis on agricultural production' (English Heritage 1991, 36). It was considered that the onset of the Middle Bronze Age defined this in cultural terms and, more importantly in physical evidence terms (Ellison 1981). Whatever the merits of this concept for other regions, or in terms of absolute chronology, or in terms of conservatism in material culture and way of life, the study area has now provided data with which to reconsider this concept. It is considered that the transition described above is most evident from the late Bronze Age rather than the middle Bronze Age within the study area. Chronology The chronology of the period is not especially well documented in terms of radiocarbon dates, when considered against the relative wealth of excavated deposits in the later Bronze Age. Some of this is partly a response by earlier excavators to the nature of the radiocarbon calibration curve which is relatively flat for the Late Bronze Age and what would be considered squandering of valuable resources for a period relatively well supplied by pottery chronology. -

Environmental Appraisal

(This page is intentionally left blank) AWE Aldermaston, Burghfield and Blacknest Historic Characterisation and Management Strategy CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Methodology 7 3. Topographic, Archaeological & Historic Background 11 4. The Heritage Significance of AWE Aldermaston, Burghfield and Blacknest 21 5. The Character Areas 27 6. Management Strategy 91 7. References 99 8. Figures: 1. Areas of Heritage Value Aldermaston Burghfield Blacknest 2. Aldermaston Character Areas Phase Plan Areas of Archaeological Potential 3. Burghfield Character Areas Phase Plan Areas of Archaeological Potential 4. Blacknest Character Areas Phase Plan Areas of Archaeological Potential page AWE Aldermaston, Burghfield and Blacknest Historic Characterisation and Management Strategy 1. INTRODUCTION This document This document provides a Historic Characterisation prohibiting it. The emphasis of Characterisation is on and Management Strategy for AWE Aldermaston, providing context – an understanding of the historic Burghfield and Blacknest. It has been prepared by continuity into which current and future development Atkins for AWE, and it sits alongside a GIS based should fit, if the distinctive quality of a place is to be collection of data that can be used to manage the maintained and enhanced. heritage resource of the sites. The document is a first for AWE, in that it draws together an evaluation of Characterisation as a way of managing change in the significance and proposals for management of the historic landscape was pioneered in Cornwall in 994, entire heritage of its sites - from the prehistoric period and has now developed into a major County level to the Cold War. The data within the AWE site GIS programme which covers more than half of England. -

Rare Plant Register

1 BSBI RARE PLANT REGISTER Berkshire & South Oxfordshire V.C. 22 MICHAEL J. CRAWLEY FRS UPDATED APRIL 2005 2 Symbols and conventions The Latin binomial (from Stace, 1997) appears on the left of the first line in bold, followed by the authority in Roman font and the English Name in italics. Names on subsequent lines in Roman font are synonyms (including names that appear in Druce’s (1897) or Bowen’s (1964) Flora of Berkshire that are different from the name of the same species in Stace). At the right hand side of the first line is a set of symbols showing - status (if non-native) - growth form - flowering time - trend in abundance (if any) The status is one of three categories: if the plant arrived in Britain after the last ice age without the direct help of humans it is defined as a native, and there is no symbol in this position. If the archaeological or documentary evidence indicates that a plant was brought to Berkshire intentionally of unintentionally by people, then that species is an alien. The alien species are in two categories ● neophytes ○ archaeophytes Neophytes are aliens that were introduced by people in recent times (post-1500 by convention) and for which we typically have precise dates for their first British and first Berkshire records. Neophytes may be naturalized (forming self-replacing populations) or casual (relying on repeated introduction). Archaeophytes are naturalized aliens that were carried about by people in pre-historic times, either intentionally for their utility, or unintentionally as contaminants of crop seeds. Archaeophytes were typically classified as natives in older floras. -

Walks Burghfield

The Country Code Walks Enjoy the countryside and respect its life and work To Goring & Oxford To Oxford To Henley-on-Thames in and around Pangbourne Guard against all risk of fire A329 A4074 Purley on A340 Sta Maidenhead To Leave all gates as found Thames A4155 Tidmarsh Burghfield Keep your dogs under close control Caversham A329 Keep to public rights of way across farmland Sta A4 M4 READING To the West the To Use gates and stiles to cross fences, hedges and walls A329 Wokingham M4 & To Horncastle A3290 Southcote Sta Leave livestock, crops and machinery alone Theale 12 A4 A327 Sta Ke nnet & Av Take your litter home A340 on A33 Sta B3031 Help to keep all water clean S B3270 London To M4 Protect wildlife, plants and trees A4 Sulhamstead 11 Shinfield Take special care on country roads Burghfield Wokingham To To Newbury To Make no unnecessary noise Ufton Nervet Three Mile A327 Cross Arborfield Burghfield Always wear appropriate footwear and take care when Common B3349 Spencers Wood walking in the town or countryside. No responsibility is A33 accepted by the authors of this leaflet for the state or Swallowfield condition from time to time of the paths comprised in these To Tadley To Basingstoke walks. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Compiled by the members of Burghfield Parish Council. Paul Lawrence and Derek Woad for the photography donated to this leaflet. Thanks also to Vic Bates, the cartographer who was responsible for producing the map & designing this leaflet. BURGHFIELD PARISH COUNCIL © Burghfield Parish Council History of Burghfield Walking for pleasure Cross over stile and turn left to walk around field perimeter to the farm drive. -

Highway Maintenance Management Plan

HIGHWAY MAINTENANCE MANAGEMENT PLAN VOLUME 4 WINTER SERVICE 2020/21 Place and Growth Directorate, Wokingham Borough Council, PO Box 153, Council Offices, Shute End, Wokingham, Berkshire. RG40 1WL Tel No. 0118 974 6000 October 2020 HIGHWAY MAINTENANCE MANAGEMENT PLAN Volume 1: Introduction & Overview Volume 2: Highway Network Maintenance Volume 3: Highway Drainage Volume 4: Winter Service Volume 5: Severe Weather and other Emergencies Volume 6: Highway Structures Volume 7: Traffic & Transport (incl Traffic Management & Road Safety) Volume 8: Street Lighting and Illuminated Signs Volume 9: Other Miscellaneous Functions Including: Sweeping and Street Cleansing Weed Control Verges and Open Spaces Trees Grass Cutting Public Rights of Way Volume 10: Highway Development Control HIGHWAY MAINTENANCE MANAGEMENT PLAN VOLUME 4 – WINTER SERVICE CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1. POLICY STATEMENT ................................................................................................. 1 2. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 3. ROAD HIERARCHY AND THE NETWORK ................................................................. 4 4. CLIENT/CONTRACTOR RELATIONSHIP ................................................................... 7 5. ROSTERING OF SUPERVISORY AND OPERATIONAL STAFF ................................ 8 6. PLANT AND VEHICLES .............................................................................................. 9 Snow Clearance ................................................................................................. -

Contaminated Land Report Template V4

Remediation Specification Pingewood Gate, AWE Burghfield AWE plc. Prepared by: Authorised by: Chris Warde Rob Jones Conrad House Beaufort Square Chepstow Monmouthshire NP16 5EP Tel 01291 621821 JER3996/Pingewood/RMS Fax 01291 627827 Revision: 1 Email [email protected] January 2009 This report has been produced by RPS within the terms of the contract with the client and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk RPS Planning and Development Ltd. Registered in England No. 02947164 Centurion Court, 85 Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RY A Member of the RPS Group Plc Planning & Development Remediation Specification, Pingewood Gate Contents Contents .............................................................................................................i 1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Report Scope .............................................................................................. 1 1.3 Remediation Objectives ............................................................................ -

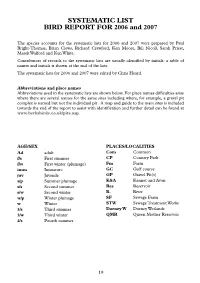

Systematic List Bird Report for 2006 and 2007

SyStematic LiSt Bird report for 2006 and 2007 The species accounts for the systematic lists for 2006 and 2007 were prepared by Paul Bright-Thomas, Brian Clews, Richard Crawford, Ken Moore, Bill Nicoll, Sarah Priest, Marek Walford and Ken White. Contributors of records to the systematic lists are usually identified by initials: a table of names and initials is shown at the end of the lists. The systematic lists for 2006 and 2007 were edited by Chris Heard. abbreviations and place names Abbreviations used in the systematic lists are shown below. For place names difficulties arise where there are several names for the same sites including where, for example, a gravel pit complex is named but not the individual pit . A map and guide to the main sites is included towards the end of the report to assist with identification and further detail can be found at www.berksbirds.co.uk/pits.asp. age/Sex PlaceS/LocaLitieS ad adult com Common f/s First summer CP Country Park f/w First winter (plumage) fm Farm imm Immature GC Golf course juv Juvenile GP Gravel Pit(s) s/p Summer plumage K&a Kennet and Avon s/s Second summer res Reservoir s/w Second winter r. River w/p Winter plumage Sf Sewage Farm w Winter StW Sewage Treatment Works 3/s Third summer dorney W Dorney Wetlands 3/w Third winter QMR Queen Mother Reservoir 4/s Fourth summer 19 2006 Bird report for 2006 mUte SWaN Cygnus olor Locally common resident Monthly maxima at the main sites were: Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Burghfield GPs 26 24 8 6 – – – – 58 81 87 49 Dinton Pastures CP 74 55 19 2 2 10 5 45 60 3 70 36 K&A Canal Newbury 69 58 73 – 88 57 – 27 42 87 – 97 R. -

The Berkshire Unitary Authorities' Joint Minerals and Waste Annual

The Berkshire Unitary Authorities’ Joint Minerals and Waste Annual Monitoring Report. 2009 (for the period April 2008 – March 2009) (Waste information for the period April 2008 – March 2009 Minerals information Jan-Dec 2008 Appendix A updates key information to November 2009) Joint Minerals and Waste Annual Monitoring Report 2009 Berkshire Joint Minerals and Waste Annual Monitoring Report 2009, Covering the period April 2008 – March 2009 (Minerals information Jan-Dec 2008) . Executive Summary i. This document aims to fulfil the requirements of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 with respect to reporting on the progress made with the preparation of Local Development Schemes (LDS) and the extent to which policies in Local Development Documents (LDD) are being successfully implemented. It also monitors and reports on nationally identified Core Output indicators and highlights any issues arising from them. ii. The following paragraphs describe progress with the JMWDF during the reporting period for the AMR. However the Report is being published at the end of 2009. An update of progress between March and November 2009 is provided in Appendix A. Preparation of the Joint Minerals and Waste Local Development Framework iii. The timetable for the preparation of the Joint Minerals and Waste Local Development Framework was revised following the issue of new Regulations in June 2008. The new LDS was approved by GOSE in September 2008. The latest version is available from the Joint Unit or can be viewed and downloaded at: http://www.berks-jspu.gov.uk iv. Following consultation on the Preferred Options version of the Joint Minerals and Waste Core Strategy in September 2007, the Submission Draft version was published in September 2008. -

KENNET VALLEY STUDY • READING - THEALE F I N a L Re P Or T • J U N E 19 8 7

Th a m es W a t e r River s Di vi s i on KENNET VALLEY STUDY • READING - THEALE F i n a l Re p or t • J u n e 19 8 7 • • • • • • SIR ALEXANDER GI BB & PARTNERS i n a ss oc i a t i on wi t h I NSTITUTE OF HYDROLOGY • T h a mes W a t er • R iver s Div i s i on KENNET VALLEY STUDY . READING - THEALE F i n a l Rep or t • J u n e 198 7 • • • • • • • SI R ALEXANDER GI BB & PARTNERS in a s soci a t i on wi t h I NSTITUTE OF HYDROLOGY • S I R A L EXA ND E R G I B B & PA RT N ER S EA RLEY HO US E C O N S U L T I N G E N G I N E E R S 4 27 LO N DO N ROA D EA RLEY P • R T N E R S • S E N I O R C O N S U L T A N T S R EADI NG RG6 IB L 0 14 C O AT E S W M • E• • n c t F. S • N on g • 0 15S E • • s C E K P . S C O TT m c r En n o t n o E N Z L L L L L L o w l 0 7 3 4 - 0 10 6 1 ( I S L I N E S ) v C O R N ET m• n e e r i B .