Late Bronze Age & Iron Age Berkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALDWORTH Footpaths, Bridleways and Byways

ALDWORTH Footpaths, Bridleways and Byways The Bell Inn FOLLOW THE COUNTRYSIDE CODE • Respect other people: consider the local community and other people enjoying the outdoors • leave gates and property as you find them and follow paths unless wider access is available. • leave no trace of your visit and take your litter home • keep dogs under effective control • plan ahead and be prepared • follow advice and local signs For the full Countryside Code and information on where to go and what to do, visit www.countrysideaccess.gov.uk No responsibility is accepted by the authors of this leaflet for the state or condition from time to time of the paths comprising these walks. Aldworth Church and Byway 4 Walking is recommended by the Government as a safe and health promoting form of exercise. However, it should be carried out with care and forethought. Always wear appropriate Aldworth Churc h footwear and take care when walking in the town or countryside. Acknowledgements © Images and text by Richard Disney and Dick and Jill Greenaway 2020. © Map compilation by Nick Hopton 2020. Path titles and routes acknowledged to West Berkshire Council Definitive Map. Aldworth Village 13 November Aldworth Parish lies in the North Wessex Downs 2020 http://aldworthvillage.uk Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty ALDWORTH PARISH COUNCIL © Aldworth Village. 2020 Further copies of this leaflet may be downloaded from © West Berkshire Countryside Society 2020 www.aldworthvillage.org www.westberkscountryside.org.uk ALDWORTH – FOOTPATHS In 871AD the Battle of Ashdown was fought Restricted Byway 17 is narrow and can be Byway 22 is an ancient tree lined track BRIDLEWAYS AND BYWAYS between the Anglo Saxons and invading overgrown in summer. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

Front Matter (PDF)

GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON MEMOIR No. 2 GEOLOGICAL RESULTS OF PETROLEUM EXPLORATION IN BRITAIN I945-I957 BY NORMAN LESLIE FALCON, M.A.F.1K.S. (CHIEF GEOLOGIST, THE BRITISH PETROLEUM COMPANY LIMITED) AND PERCY EDWARD KENT, D.Sc., Ph.D. (GEOLOGICAL ADVISER, BP EXPLORATXON [CANADA]) LONDON 4- AUGUST, I960 LIST OF PLATES PLATE I, FIG. 1. Hypothetical section through Kingsclere and Faringdon borings. (By R. G. W. BRU~STRO~) 2. Interpretative section through Fordon No. 1. Based on seismic reflection and drilling results, taking into account the probability of faulting of the type exposed in the Howardian Hills Jurassic outcrop. II. Borehole sections in West Yorkshire. (By A. P. TERRIS) III. Borehole sections in the Carboniferous rocks of Scotland. IV. Type column of the Upper Carboniferous succession in the Eakring area, showing lithological marker beds. (By M. W. STI~O~C) V. Structure contour map of the Top Hard (Barnsley) Seam in the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Coalfield. Scale : 1 inch to 2 miles. LIST OF TABLES Data from exploration wells, 1945-1957, m-- TABLE I. Southern England and the South Midlands II. The East Midlands III. East and West Yorkshire IV. Lancashire and the West Midlands V. Scotland LIST OF FIGURES IN THE TEXT Page Fig. 1. General map of areas explored to the end of 1957 6 2. Arreton : gravity residuals and reflection contours . 8 Ashdown : seismic interpretation of structure after drilling. Depths shown are of Great Oolite below sea,level 9 4. Mesozoic borehole sections in southern England 10 5. Faringdon area : gravity residuals and seismic refraction structure 14 6. -

Wharfside Mews?

A SELECTION OF ELEVEN CONTEMPORARY HOUSES IN A UNIQUE WATERSIDE LOCATION 2017 1 MASTON W ALDER HARF Follow the historic Kennet & Avon Canal as it meanders through rural Berkshire and you will find Aldermaston Wharf - a small parish just 1.5 miles north-east of picturesque Aldermaston village. Once a busy industrial hub, Aldermaston Wharf is now a tranquil, unspoilt location, perfect for exploring the beautiful Kennet & Avon Canal. As you would imagine being right next to the water, there is an abundance of wildlife including ducks, kingfishers, herons and swans. The canal itself will lead you to Newbury, Reading or beyond and is ideal for exploring on foot or by bike. Other attractions at the Wharf include the popular Kennet & Avon Canal Trust Tea Rooms - perfect for an enjoyable afternoon tea, watching the world go by, and the Marina, where you’ll see the colourful narrowboats and barges coming and going. It’s a truly unique location, with plenty to see and do without feeling busy or overcrowded and what better way to enjoy it than a stunning new home at Wharfside Mews? 2 ERFECT LOCATI A P ON ALDERMASTON WHARF From country pursuits to urban chic, whatever your lifestyle - Wharfside Mews is ideally situated for both town and country. Wharfside Mews Aldermaston village Imagine living in a beautiful rural location Historic Aldermaston village can be without having to give up access to major traced back as far as the 9th century, towns and all the facilities they offer. with the majority of houses in the village dating from the 17th to the 19th centuries. -

260 FAR BERKSHIRE. [KELLY's Farmers-Continued

260 FAR BERKSHIRE. [KELLY'S FARMERs-continued. Bennett William, Head's farm, Cheddle- Brown C. Curridge, Chieveley,Newbury Adams Charles William, Red house, worth, Wantage Brown Francis P. Compton, Newbury Cumnor (Oxford) Benning Hy.Ashridge farm,Wokingh'm Brown John, Clapton farm, Kintbury, Adams George, PidnelI farm, Faringdon Benning- Mark, King's frm. Wokingham Hungerford Adams Richard, Grange farm, Shaw, Besley Lawrence,EastHendred,Wantage Brown John, Radley, Abingdon Newbury Betteridge Henry,EastHanney,Wantage Brown John, ""'est Lockinge, Wantage Adey George, Broad common, Broad Betteridge J.H.Hill fm.Steventon RS.O Brown Stephen, Great Fawley,Wantage Hinton, Twyford R.S.O Betteridge Richard Hopkins, Milton hill, Brown Wm.BroadHinton,TwyfordR.S.0 Adnams James, Cold Ash farm, Cold Milton, Steventon RS.O Brown W. Green fm.Compton, Newbury Ash, Newbury Betteridge Richard H. Steventon RS.O Buckeridge David, Inkpen, Hungerford Alden Robert Rhodes, Eastwick farm, Bettridge William, Place farm, Streat- Buckle Anthony, Lollingdon,CholseyS.O New Hinksey, Oxford ley, Reading Bucknell A.B. Middle fm. Ufton,Readng Alder Frederick, Childrey, Wantage Bew E. Middle farm, Eastbury,Swindon Budd Geo.Mousefield fm.Shaw,Newbury Aldridge Henry, De la Beche farm, Ald- Bew Henry, Eastbury, Swindon Bulkley Arthur, Canhurst farm, Knowl worth, Reading Billington F.W. Sweatman's fm.Cumnor hill, Twyford R.S.a Aldridge John, Shalbourn, Hungerford Binfield Thomas, Hinton farm, Broad Bullock George, Eaton, Abingdon Alexander Edward, Aldworth, Reading Hinton, -

Burnt Mounds, Unenclosed Platform Settlements and Information on Burnt Stone Activity in the River Clyde and Tweed Valleys of South Lanarkshire and Peeblesshire

Burnt Mounds, Unenclosed Platform Settlements and information on burnt stone activity in the River Clyde and Tweed valleys of South Lanarkshire and Peeblesshire. by Tam Ward 2013 Burnt Mounds, Unenclosed Platform Settlements and information on burnt stone activity in the River Clyde and Tweed valleys of South Lanarkshire and Peeblesshire. PAGE 1 Abstract Throughout the work of Biggar Archaeology Group’s (BAG) projects, burnt stone is shown to have played an important aspect of life in the past. Sometimes deliberately burnt as a method of transference of heat in the case of burnt mounds and where water was heated, and also in pits where dry cooking may have taken place, to co-incidentally being burnt in hearths and fireplaces during all periods from the Mesolithic to Post Medieval times. The recognition of burnt stone in the archaeology of the Southern Uplands of Scotland has been fundamental to interpretations by the Group in their voluntary work. The greatest manifestation of burnt stone appears in burnt mounds (BM), a relatively new class of site for the area of the Clyde and Tweed valleys, albeit now one of the most numerous. The subject of burnt stone in the general archaeology of BAG projects is also considered. Unenclosed Platform Settlements (UPS) are also a numerous site type in the area and perhaps are poorly understood in terms of their spatial distribution, chronology and function, as indeed are the BM. It is regarding these sites (BM & UPS) and their possible relationship with each other that this paper principally seeks to address. Burnt Mounds, Unenclosed Platform Settlements and information on burnt stone activity in the River Clyde and Tweed valleys of South Lanarkshire and Peeblesshire. -

Blewbury Neighbourhood Development Plan Housing Needs Survey: Free-Form Comments This Is a Summary of Open-Ended Comments Made in Response to Questions in the Survey

! !"#$%&'()*#+,-%.&'-../) 0#1#".23#45)6"74) 89:;)<)89=:) "##$%&'($)! %"#$%&'(4#+,-%.&'-../2"74>.',) :;)?2'+")89:;) ! @.45#45A) "##$%&'*!"+!,-.'%./$0!1$2$-!34$-5672)!.%&!8-79%&2.:$-!;677&'%/!'%!<6$2=9->! "##$%&'*!<+!?79)'%/!@$$&)!19-4$>! "##$%&'*!A+!B.%&)(.#$!AC.-.(:$-!"))$))D$%:! "##$%&'*!,+!E'66./$!AC.-.(:$-!"))$))D$%:! ! ! ! ! ! !""#$%&'(!)()!"#$%#&'()*'+'"),-'"./0+1)#%2)3"04%2+#5'"! !"##$%&'(%&()"*+,-./) ! ! ! ! "#$%!&'()!$%!$*+)*+$,*'--.!-)/+!0-'*1! ! !""#$%&'(!!"!!"#$%#&'()*'+'"),-'"./0+1)#%2)3"04%2+#5'"! !"##$%&'(%&()"*+,-./! !"#$%&'($)**+$ !"#$%&%"'#(%)$*+#,)$'*#-.#/0%123$(#4)5%#*3..%$%6#*%1%$#-5%$.0-1*#)"6#7$-3"61)'%$#.0--68"7# 63$8"7# ,%$8-6*# -.# 1%'# 1%)'4%$9# :4%$%# 8*# &-"&%$"# '4)'# .3$'4%$# 4-3*8"7# 6%5%0-,;%"'# 8"# '4%# 5800)7%#&-306#%<)&%$2)'%#'4%#,$-20%;9#!"#'48*#),,%"68<#1%#%<,0-$%#14(#*3&4#,$-20%;*#-&&3$# )"6# &-"*86%$# '4%# ,0)""8"7# ,-08&(# 7386)"&%# '4)'# ;874'# 2%# "%%6%6# 8"# '4%# /0%123$(# =%8742-3$4--6#>%5%0-,;%"'#?0)"#'-#%"*3$%#'4%#*8'3)'8-"#6-%*#"-'#1-$*%"9# @%1%$# -5%$.0-1# -&&3$*# 14%"# $)1+# 3"'$%)'%6# *%1)7%# A1)*'%1)'%$B# 2$8;*# -5%$# .$-;# '4%# ;)"4-0%*#)"6#73008%*#-.#'4%#*%1%$)7%#"%'1-$C#'-#.0--6#0)"6+#7)$6%"*+#$-)6*+#,)'4*#)"6+#8"#'4%# 1-$*'#&)*%*+#,%-,0%D*#4-3*%*9#@3&4#3"'$%)'%6#*%1)7%#8*#"-'#-"0(#3",0%)*)"'#'-#*%%#)"6#*;%00# 23'#8'#)0*-#&)"#,-*%#)#'4$%)'#'-#43;)"#4%)0'4#)"6#'4%#%"58$-";%"'9## E5%$.0-1*# -&&3$# ;-*'# &-;;-"0(# 63$8"7# 4%)5(# $)8".)00# A*'-$;B# %5%"'*# -$# ).'%$# ,%$8-6*# -.# ,$-0-"7%6# $)8".)009# :4%(# )$%# 3*3)00(# &)3*%6# 2(# 0)$7%# 5-03;%*# -.# *3$.)&%# 1)'%$# -$# 7$-3"61)'%$# -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

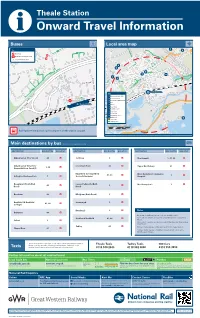

Theale Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Theale Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map IK Key C A Bus Stop B Rail replacement Bus Stop A Station Entrance/Exit 1 0 m in ut H es w a CF lk in g d LS is ta PO n BP c e TG L Theale Station Key BP Arlington Business Park C Calcot Sainsbury CF Cricket & Football Grounds IK Ikea Theale Station L Library LS Local Shops FG Football Ground PO Post Office SC Sailing Club TG Theale Green School H Village Hall SC Cycle routes Walking routes km 0 0.5 Rail replacement buses/coaches depart from the station car park. 0 Miles 0.25 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Aldermaston (The Street) 44 A Colthrop 1 A Thatcham ^ 1, 41, 44 A Aldermaston Wharf (for Crookham Park 44 A Upper Bucklebury 41 A 1, 44 A Kennet & Avon Canal) ^ Englefield (for Englefield West Berkshire Community 41, 44 A 1 A Arlington Business Park 1 B House & Gardens) Hospital Baughurst (Heath End Lower Padworth (Bath A 44 A 1 A Woolhampton [ 1 Road) Road) Beenham 44 A Midgham (Bath Road) 1 A Bradfield (& Bradfield Newbury ^ 1 A 41, 44 A College) Reading ^ 1 B Notes Brimpton 44 A Bus route 1 (Jet Black) operates a frequent daily service. Southend Bradfield 41, 44 A Bus route 41 operates one journey a day Mondays to Fridays from Calcot 1 B Theale. -

Hillside the Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Hillside the Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Price Guide: £460,000 Freehold

Hillside The Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Hillside The Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Price Guide: £460,000 Freehold A delightful extended semi detached family home with a garage and beautiful south west facing garden • Entrance hallway • Living room • Large fitted kitchen/dining room • 4 Bedrooms • Family bathroom • Garage • Driveway parking • Large rear garden • Double glazing • Oil fired central heating Location Padworth is 4 miles to the west of Junction 12 of the M4 at Theale and Reading and some 8 miles to the east of Newbury. It is a small village adjoining picturesque Aldermaston Wharf just to the south of the A4. It is ideally located for excellent communications being 7 miles west of Reading and the property is only a 10 minute walk from Aldermaston station. The surrounding countryside is particularly attractive and comprises Bucklebury Common and Chapel Row to the north (an area of outstanding natural beauty). The major towns of Reading and Newbury offer excellent local facilities. A lovely family home and garden ! Michael Simpson Description This lovely extended family home offers spacious and flexible accommodation arranged over two floors comprising an entrance hallway, cosy living room with open fire, a good size open plan fitted kitchen/dining room and cloakroom on the ground floor. On the first floor are four double bedrooms and the family bathroom. Other features include oil fired central heating and double glazing. Outside The front of the property is approached via the driveway which leads to the front door and garage. The rear garden has established flower bed borders offering a variety of lovely shrubs, plants and flowers. -

Westridge Manor WESTRIDGE GREEN • BERKSHIRE

Westridge Manor WESTRIDGE GREEN • BERKSHIRE Westridge Manor WESTRIDGE GREEN • BERKSHIRE An exceptional 18th century Manor house with wonderful gardens Aldworth 1 mile • Streatley 2 miles Goring 2.5 miles (London Paddington from 57 minutes) • Pangbourne 6 miles Theale/M4 (J.12) 10 miles • M4 (J.13) 10 miles • Newbury 12 miles Reading 12 miles (London Paddington from 26 minutes) Distances and times approximate Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Sitting room Study • Kitchen/breakfast room • Larder • Utility room 2 cloakrooms and cellar Master bedroom with bathroom and dressing room/bedroom 2 5 further bedrooms • 2 further bathrooms Garaging • Stabling • Granary • Tractor shed • Wood shed • Greenhouse Delightful formal gardens with swimming pool, pool house and tennis court • Paddocks Approximate gross internal area: 6,442 sq.ft. Manor House: 4,874 sq.ft. • Garage and Outbuildings: 1,568 sq.ft. In all about 3.88 acres These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Westridge Manor Westridge Manor is a substantial Grade II Listed property built in the 18th The dining room, sitting room and study all have open fireplaces. century with later additions. The attractive west elevation is Georgian in The triple aspect kitchen/breakfast room, with 4 oven Aga and central appearance and is constructed of red brick under a tile roof. island, overlooks the pretty gardens. A door leads onto a secluded west The house includes approximately 4,500 sq.ft. of living space and includes facing terrace. -

Autumn House, Birds Lane, Midgham, Reading, Berkshire Autumn House Room, Both of Which Have Chic, Contemporary Birds Lane, Suites

Autumn House, Birds Lane, Midgham, Reading, Berkshire Autumn House room, both of which have chic, contemporary Birds Lane, suites. Midgham, Outside To the front of the property there is an area of lawn Reading, Berkshire and a block-paved driveway, providing parking space for several vehicles. The garage provides RG7 5UL ample storage and workshop space, while timber gates open onto a paved and gravel area to the A beautifully presented 6 bedroom family home side of the house, which could be used for further with modern accommodation in a peaceful parking. The house benefits from solar panels. The village location garden to the rear has an area of paved terracing Midgham mainline station 1.8 miles (57 minutes immediately at the back of the house, a well- to London Paddington via Reading), Thatcham maintained lawn, a rockery and a further small area town centre 3.2 miles, Newbury town centre 6.0 of patio to the side, as well as established border miles, M4 (Jct 12) 7.8 miles hedgerow. Location Reception hall | Sitting room | Study/office The village of Midgham is set in a rural location Dining area | Kitchen | Utility | Cloakroom | 6 close to the popular Berkshire towns of Thatcham Bedrooms | Dressing room | Bathroom | Shower and Newbury. There is a local pub in Midgham, room | Garden | EPC rating C while the neighbouring village of Woolhampton has a local shop, a pub and a primary school, as well as The property the independent Elstree School. The nearby village Autumn House is a superb, detached home, which of Aldermaston Wharf provides further everyday has been extended and modernised to provide amenities, including local shops.