Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

Goran Navojec Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ)

Goran Navojec Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) Ministry of Love https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ministry-of-love-28154706/actors The Romanoffs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-romanoffs-46031730/actors Vukovar: The Way Home https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vukovar%3A-the-way-home-7943427/actors Long Dark Night https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/long-dark-night-1156694/actors Territorio comanche https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/territorio-comanche-21819908/actors Russian Meat https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/russian-meat-7382080/actors ÄŒetverored https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%C4%8Detverored-1565253/actors Forest Creatures https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/forest-creatures-12646204/actors Celestial Body https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/celestial-body-5057890/actors Falsifier https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/falsifier-12760558/actors God Forbid a Worse Thing https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/god-forbid-a-worse-thing-should-happen-5575860/actors Should Happen Holidays in the Sun https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/holidays-in-the-sun-16083347/actors A Perfect Day https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-perfect-day-16389827/actors Mare https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mare-105157284/actors Libertas https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/libertas-6541454/actors The Brave Adventures of a https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-brave-adventures-of-a-little-shoemaker-21999962/actors Little Shoemaker -

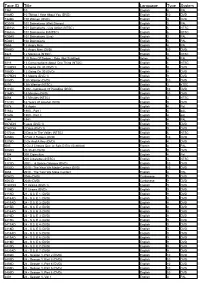

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Deepa Mehta (See More on Page 53)

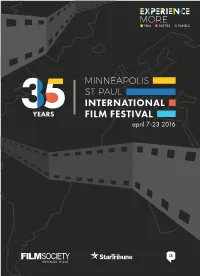

table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Experimental Cinema: Welcome to the Festival 3 Celluloid 166 The Film Society 14 Pixels 167 Meet the Programmers 44 Beyond the Frame 167 Membership 19 Annual Fund 21 Letters 23 Short Films Ticket and Box Offce Info 26 Childish Shorts 165 Sponsors 29 Shorts Programs 168 Community Partners 32 Music Videos 175 Consulate and Community Support 32 Shorts Before Features 177 MSPFilm Education Credits About 34 Staff 179 Youth Events 35 Advisory Groups and Volunteers 180 Youth Juries 36 Acknowledgements 181 Panel Discussions 38 Film Society Members 182 Off-Screen Indexes Galas, Parties & Events 40 Schedule Grid 5 Ticket Stub Deals 43 Title Index 186 Origin Index 188 Special Programs Voices Index 190 Spotlight on the World: inFLUX 47 Shorts Index 193 Women and Film 49 Venue Maps 194 LGBTQ Currents 51 Tribute 53 Emerging Filmmaker Competition 55 Documentary Competition 57 Minnesota Made Competition 61 Shorts Competition 59 facebook.com/mspflmsociety Film Programs Special Presentations 63 @mspflmsociety Asian Frontiers 72 #MSPIFF Cine Latino 80 Images of Africa 88 Midnight Sun 92 youtube.com/mspflmfestival Documentaries 98 World Cinema 126 New American Visions 152 Dark Out 156 Childish Films 160 2 welcome FILM SOCIETY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S WELCOME Dear Festival-goers… This year, the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival celebrates its 35th anniversary, making it one of the longest-running festivals in the country. On this occasion, we are particularly proud to be able to say that because of your growing interest and support, our Festival, one of this community’s most anticipated annual events and outstanding treasures, continues to gain momentum, develop, expand and thrive… Over 35 years, while retaining a unique flavor and core mission to bring you the best in international independent cinema, our Festival has evolved from a Eurocentric to a global perspective, presenting an ever-broadening spectrum of new and notable film that would not otherwise be seen in the region. -

FILM FESTIVAL 22Nd - 29Th November 2012

UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE EMBASSY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA IN PRETORIA SERBIAN ARTS AND CULTURE SOCIETY AFRICA SERBIAN FILM FESTIVAL 22nd - 29th November 2012 NU METRO, MONTECASINO An author’s perspective of the world Film, as a sublimation of all arts, is a true medium, a universal vehicle with which the broader public is presented with a world view, as seen by the eye of the fi lmmaker. Nowadays, due to the global economic crisis, which is ironically producing technological and all sorts of other develop- ments, an increasing number of people are pushed to the margins of average standards of living, and fi lmmakers are given the chance to bring under their ‘protection’ millions of disillusioned people with their fi lmmaking capabilities. Art, throughout its history, has always praised but has also been heavily critical of its subject. Film is not just that. Film is that and so much more. Film is life itself and beyond life. Film is everything many of us dream about but never dare to say out loud. That is why people love fi lms. That is why it is eternal. It tears down boundaries and brings together cul- tures. It awakens curiosity and builds bridges from one far away coast to another. Film is a ‘great lie’ but an even greater truth. Yugoslavian, and today the Serbian fi lm industry has always been ‘in trend’. It might sound harsh but, unfortunately, this region has always provided ample ‘material’ for fi lms. Under our Balkan clouds there has been an ongoing battle about which people are older, which came and settled fi rst, who started it and who will be fi rst to leave and such battles have been and continue to be an inspiration to fi lm producers. -

Japanese Haiku Second Series ;

JAPANESE HAIKU SECOND SERIES ; . *. m $ ( 1 / • i I due roan seasons JAPANESE HAIKU WRITTEN BY BASHO•BUSON ISSA • SHIKI • AND MANY OTHERS TRANSLATION BY PETER BEILENSON THE PETER PAUPER PRESS MOUNT VERNON • NEW YORK COPYRIGHT »958 © BY THE PETER PAUPER PRESS i A NOTE ON JAPANESE HAIKU The haiku is a seventeen-syllable poetic form that has been written in Japan for three hun dred years. It has been enormously popular with out becoming banal. For the haiku does not make a complete poem in our usual sense; it is a lightly- sketched picture the reader is expected to fill in from his own memories. Often there are two pic tures, and the reader is expected to respond with heightened awareness of the mystical relationship between non-related subjects. This mystical awareness is one of the seekings of Zen Buddhism, and was introduced into haiku by the first, best-loved, greatest master of the form, Basho (1644-1694). A second master was Buson (1715-1783), a poet less interested in mystical re lationships than in exquisite vignettes. A third was Issa (1763-1827), pathetic, wryly humorous, ut terly individual. A fourth was Shiki (1866-1902) — a modern Buson who gives us perfectly-phrased glimpses of everyday scenes and situations. Almost every haiku holds a season key-word; often the name of the season itself, otherwise a seasonal reference easily understood. The reader must take this key-word not as a statement, but as the author’s cue to him, so that he can call up 3 in himself his own associations and nostalgias, and read the little poem against this background. -

Disillusioned Serbians Head for China's Promised Land

Serbians now live and work in China, mostly in large cities like Beijing andShanghai(pictured). cities like inlarge inChina,mostly andwork live Serbians now 1,000 thataround andsomeSerbianmedia suggest by manyexpats offered Unofficial numbers +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 Belgrade in Concern Sparks Boom Estate Real Page 7 Issue No. No. Issue [email protected] 260 Friday, October 12 - Thursday, October 25,2018 October 12-Thursday, October Friday, Photo: Pixabay/shanghaibowen Photo: Skilled, adventurous young Serbians young adventurous Skilled, China – lured by the attractive wages wages attractive the by –lured China enough money for a decent life? She She life? adecent for money enough earning of incapable she was herself: adds. she reality,” of colour the got BIRN. told Education, Physical and Sports of ulty Fac Belgrade’s a MAfrom holds who Sparovic, didn’t,” they –but world real the change glasses would rose-tinted my thought and inlove Ifell then But out. tryit to abroad going Serbia and emigrate. to plan her about forget her made almost things These two liked. A Ivana Ivana Sparovic soon started questioning questioning soonstarted Sparovic glasses the –but remained “The love leaving about thought long “I had PROMISED LAND PROMISED SERBIANS HEAD HEAD SERBIANS NIKOLIC are increasingly going to work in in towork going increasingly are place apretty just than more Ljubljana: Page 10 offered in Asia’s economic giant. economic Asia’s in offered DISILLUSIONED love and had a job she ajobshe had and love in madly was She thing. every had she vinced con was Ana Sparovic 26-year-old point, t one FOR CHINA’S CHINA’S FOR - - - BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY INSIGHTISPUBLISHED BELGRADE for China. -

From the on Inal Document. What Can I Write About?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 655 CS 511 615 TITLE What Can I Write about? 7,000 Topics for High School Students. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5654-1 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 153p.; Based on the original edition by David Powell (ED 204 814). AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 56541-1659: $17.95, members; $23.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS High Schools; *Writing (Composition); Writing Assignments; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS Genre Approach; *Writing Topics ABSTRACT Substantially updated for today's world, this second edition offers chapters on 12 different categories of writing, each of which is briefly introduced with a definition, notes on appropriate writing strategies, and suggestions for using the book to locate topics. Types of writing covered include description, comparison/contrast, process, narrative, classification/division, cause-and-effect writing, exposition, argumentation, definition, research-and-report writing, creative writing, and critical writing. Ideas in the book range from the profound to the everyday to the topical--e.g., describe a terrible beauty; write a narrative about the ultimate eccentric; classify kinds of body alterations. With hundreds of new topics, the book is intended to be a resource for teachers and students alike. (NKA) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the on inal document. -

Dalibor Matanić Ankica Jurić Tilić Goran Marković Screenwriter, Director Producer Lead Actor

The High Sun · Soleil de plomb THREE DECADES TWO NATIONS ONE LOVE ZVIZDANWritten and directed by Dalibor Matanić SYNOPSIS The High Sun shines a light on three love stories, set in three consecutive decades, in two neighbouring Balkan villages with a long history of inter-ethnic hatred. It is a film about the fragility – and intensity – of forbidden love. The High Sun shines a light on three love stories, set in three In the second story, set in 2001, the war is over but the lovers consecutive decades, in two neighbouring Balkan villages with a find it impossible to turn their infatuation into an ongoing long history of inter-ethnic hatred. It is a film about the fragility – relationship: the scars of the war are still too fresh and cannot and intensity – of forbidden love. heal that easily. In the first story, set in 1991, a romantic attraction is forced under- The third story takes place in 2011, when love can finally take root, ground when love becomes a forbidden luxury in the pre-war if the lovers can break free of the past. Evil and suspicion have not atmosphere of madness, confusion and fear. completely vanished from their lives and catharsis is not easy to achieve, but it is possible once again. THE HIGH SUN Director’s note The High Sun celebrates selflessness and love – the very best of human nature that is still struggling to re-emerge victorious in our region. Because there is one thing I am sure about: at the end of the day, politics and extreme nationalism never win. -

The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema After the Break

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses April 2014 The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema after the Break Dijana Jelaca University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jelaca, Dijana, "The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema after the Break" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 10. https://doi.org/10.7275/vztj-0y40 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/10 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GENEALOGY OF DISLOCATED MEMORY: YUGOSLAV CINEMA AFTER THE BREAK A Dissertation Presented by DIJANA JELACA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2014 Department of Communication © Copyright by Dijana Jelaca 2014 All Rights Reserved THE GENEALOGY OF DISLOCATED MEMORY: YUGOSLAV CINEMA AFTER THE BREAK A Dissertation Presented by DIJANA JELACA Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Leda Cooks, Chair _______________________________________ Anne Ciecko, Member _______________________________________ Lisa Henderson, Member _______________________________________ James Hicks, Member ____________________________________ Erica Scharrer, Department Head Department of Communication TO LOST CHILDHOODS, ACROSS BORDERS, AND TO MY FAMILY, ACROSS OCEANS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is about a part of the world that I call “home” even though that place no longer physically exists. I belong to that “lost generation” of youth whose childhoods ended abruptly when Yugoslavia went up in flames. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Cinematic Representations of Nationalist-Religious Ideology in Serbian Films during the 1990s Milja Radovic Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh March 2009 THESIS DECLARATION FORM This thesis is being submitted for the degree of PhD, at the University of Edinburgh. I hereby certify that this PhD thesis is my own work and I am responsible for its contents. I confirm that this work has not previously been submitted for any other degree. This thesis is the result of my own independent research, except where stated. Other sources used are properly acknowledged. Milja Radovic March 2009, Edinburgh Abstract of the Thesis This thesis is a critical exploration of Serbian film during the 1990s and its potential to provide a critique of the regime of Slobodan Milosevic. -

Yugoslav Cinema

Egemia, 2018; 3: 31-49 31 TRANSFORMATION OF TRAUMATIC CHARACTERS IN POST- YUGOSLAV CINEMA Ahmet Ender UYSAL* ABSTRACT This study examines the changes Yugoslav cinema realized from the 1980s to the 2000s, and seeks to see the contributions of three important post-Yugoslav directors to the transformation of the cinema characters. The post-Yugoslav states emerged after the disintegration of Yugoslavia, and they underwent political and cultural changes as a result of the collapse of the former Yugoslav socialism and the post-civil war. Post- Yugoslav cinema, which took its share from these changes, experienced crises of national identity and modernization. Examining these changes in cinema with cinematic characters is also very important in terms of visualizing cultural and economic changes in a cinematic sense. The real problem here is where the boundary of this change will be drawn. This is because, although the characters in post-Yugoslavian cinema have been transformed, there is still some cinematic tradition that continues today. Post-Yugoslav cinema will therefore be considered within the period of 1980s. Keywords: Post-Yugoslav cinema, trauma, cinematic characters * Arş. Gör., Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi, Sinema-Televizyon Bölümü / VAN E-posta: [email protected] Makale Gönderim Tarihi: 14.06.2018 – Makale Kabul Tarihi: 16.10.2018 32 Egemia, 2018; 3: 31-49 INTRODUCTION Often, the concept of post-Yugoslavian cinema offers curative effects on rejection of failure and the search for hope, and becomes a common stake of new countries emerging after the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia, which is increasingly adopted in the field of film studies (Šprah, 2015: 184).