Thomas Waller Gissing Before His Move to Wakefield: Some Materials Towards His Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Echo 2014 Aug &

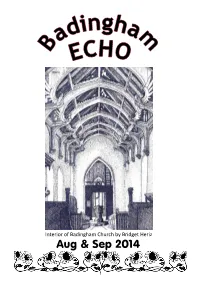

ngh adi am B ECHO Interior of Badingham Church by Bridget Heriz Aug & Sep 2014 1 BADINGHAM DIARY Maypole - Brandeston Walk Wed 13th August Call 638257 for details Village Supper Tue 19th August White Horse 7.30pm WI Thu 28th August Village Hall 7.30pm Harvest Festival & BBQ Sun 7th September Church 11am Maypole Wed 10tth September Call 638257 for details BCC Committee Meeting Thu 11tth September Village Hall 7.30pm SHCT Cycle Ride Sat 13th September Call 638010 for details Village Supper Tue 16tth September White Horse 7.30pm WI Thu 25th September Village Hall 7.30pm Playschool Jumble Sale Sat 4th October Riverside Centre 1pm Village Quiz Tue 7th October White Horse 8pm BCC Autumn Social Sat 18th October Village Hall 9.30-11.30 Latest Village News & Events Check for updates on www.badingham.org.uk All the latest news will be posted here Don’t forget to tell Carl when you have news or events that you need to publicise: [email protected] Always grateful for your contributions: stories, memories and pictures. So, please start scribbling! Remember, I can only print what I am sent so if you need help, ideas or publicity for an event don’t forget to let me know. The copy deadline for the next Echo is: 15th September Please send news, articles etc to: Tish King T: 01728 638259 Email : [email protected] 2 Notes from the Editor Last Sunday afternoon we sat under umbrellas for our picnic tea but, as Ann said, it was most enjoyable and the weather could have been much worse . -

Otley Campus Bus Timetable

OTLEY CAMPUS BUS TIMETABLE 116 / 118: Ipswich to Otley Campus: OC5: Bures to Otley Campus Ipswich, Railway Station (Stand B) 0820 - Bures, Eight Bell Public House R R Ipswich, Old Cattle Market Bus Station (L) 0825 1703 Little Cornard, Spout Lane Bus Shelter R R Ipswich Tower Ramparts, Suffolk Bus Stop - 1658 Great Cornard, Bus stop in Highbury Way 0720 R Westerfield, opp Railway Road 0833 1651 Great Cornard, Bus stop by Shopping Centre 0722 R Witnesham, adj Weyland Road 0839 1645 Sudbury, Bus Station 0727 1753 Swilland, adj Church Lane 0842 1642 Sudbury Industrial Estate, Roundabout A134/ B1115 Bus Layby 0732 1748 Otley Campus 0845 1639 Polstead, Brewers Arms 0742 1738 Hadleigh, Bus Station Magdalen Road 0750 1730 118: Stradbroke to Otley Campus: Sproughton, Wild Man 0805 1715 Stradbroke, Queens Street, Church 0715 1825 Otley Campus 0845 1640 Laxfield, B1117, opp Village Hall 0721 R Badingham, Mill Road, Pound Lodge (S/B) 0730 R OC6: Clacton to Otley Campus Dennington, A1120 B1116, Queens Head 0734 R Clacton, Railway Station 0655 1830 Framlingham, Bridge Street (White Horse, return) 0751 1759 Weeley Heath, Memorial 0705 1820 Kettleborough, The Street, opp Church Road 0802 1752 Weeley, Fiat Garage 0710 1815 Brandeston, Mutton Lane, opp Queens Head 0805 1749 Wivenhoe, The Flag PH (Bus Shelter) 0730 1755 Cretingham, The Street, New Bell 0808 1746 Colchester, Ipswich Road, Premier Inn 0745 1740 Otley, Chapel Road, opp Shop 0816 1738 Capel St Mary, White Horse Pub (AM), A12 Slip road (PM) 0805 1720 Otley Campus 0819 1735 Otley Campus 0845 -

Fact Sheet the Queen's Coronation 1953 Children's Outfits

FACT SHEET 24 January 2013 The Queen’s Coronation 1953 Coronation outfits of Prince Charles and Princess Anne The clothes worn by Prince Charles and Princess Anne on Coronation Day were supplied by the children’s outfitter Miss Hodgson, of 33 Sloane Street, London, who was a regular supplier to the Royal Family at the time. The four-year-old Prince’s outfit consisted of a cream silk shirt with a lace jabot and lace- trimmed cuffs, and cream woollen trousers. He wore black patent shoes with buckles. The Prince, who was known as The Duke of Cornwall in 1953, also wore his Coronation Medal. Princess Anne, who was two, wore a dress of cream silk and lace with a silk sash and silk-covered buttons, with matching cream, silk ballet pumps. The Princess did not attend the Coronation ceremony in Westminster Abbey, as she was considered too young. The children’s elegant, yet relatively informal outfits were a marked contrast to those worn by The Queen, then Princess Elizabeth, and Princess Margaret, for the coronation of their father, King George VI, on 11 May 1937. On that occasion, the children, who were slightly older (aged 11 and six respectively), wore long dresses, robes and coronets – as was the conventional dress for adults of their rank for a coronation. The display of the children’s outfits will be supplemented by film footage and photographs taken at Buckingham Palace, famously recording the children waving off The Queen as she departed for Westminster Abbey. Prince Charles later left the Palace in his own carriage, accompanied by his nanny. -

The Badingham Parish Plan 2007

Badingham Parish Plan Report This report has been prepared in accordance with the guidance set out in the former Countryside Agency document “Parish Plans – Guidance for parish and town councils” CA 122. It complies with the guidance set out by Suffolk ACRE in their “Parish Plan Sheets”. Report ©: Badingham Parish Council December 2007. Editor: Bill Dicks Distributed by: Badingham Parish Council Parish Plan steering sub- committee c/o Village Hall, Low Street, BADINGHAM, Suffolk. Badingham website: www.badingham.org.uk Maps: licensed with thanks from Ordnance Survey. Photographs: 4 -6 & 10 © Linn Barringer http://WoodbridgeSuffolk.info; Front Cover & 13 © R. Foster; 7 © T. Hill; Back Cover, 1-3, 9, 11 & 15 © C. Meigh; 12 © B.D. O’Farrell; 8 © J. King; 14 © S. Osborne. Throughout this document: Noteworthy points are highlighted like this. Licence no. 100046955 1. Recommendations for action are shown like this. FOREWORD Many congratulations to everyone who has been involved in the Badingham Parish plan Project. I know just how much time and effort it takes to drive this kind of project to completion. The Plan will be invaluable in protecting the character of the village in the future and at the same time will set out what the village needs in terms of services and infrastructure. Well done to everybody involved. Sir Michael Lord, MP Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons This Parish Plan is a truly worthwhile project, the result of tireless effort by many Badingham residents. In particular I saw at first hand the vision of Paul Osborne and the tenacity with which he stuck to the task and encouraged others to play their part. -

Site Allocations Assessment 2014 SCDC

MAP BOOKLET to accompany Issues and Options consultation on Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies Local Plan Document Consultation Period 15th December 2014 - 27th February 2015 Suffolk Coastal…where quality of life counts Framlingham Housing Market Area Housing Market Settlement/Parish Area Framlingham Badingham, Bramfield, Brandeston, Bruisyard, Chediston, Cookley, Cransford, Cratfield, Dennington, Earl Soham, Easton, Framlingham, Great Glemham, Heveningham, Huntingfield, Kettleburgh, Linstead Magna, Linstead Parva, Marlesford, Parham, Peasenhall, Rendham, Saxtead, Sibton, Sweffling, Thorington, Ubbeston, Walpole, Wenhaston, Yoxford Settlements & Parishes with no maps Settlement/Parish No change in settlement due to: Cookley Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Framlingham Currently working on a Neighbourhood Plan, so not considered in Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies DPD Great Glemham No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Huntingfield No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Linstead Magna Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Linstead Parva Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Sibton Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Thorington Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Ubbeston Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Walpole No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) The Settlement Hierarchy (Policy SP19) is explained in the Suffolk Coastal District Local Plan, on page 61 and can be found via the following link: http://www.suffolkcoastal.gov.uk/assets/Documents/LDF/SuffolkCoastalDistrictLocalPlanJuly2013.p df This document contains a number of maps, with each one containing different information. -

The Willows, Badingham Framlingham - 5.7 Miles Woodbridge -16.8 Miles Aldeburgh - 15.2 Miles

The Willows, Badingham Framlingham - 5.7 miles Woodbridge -16.8 miles Aldeburgh - 15.2 miles A substantial detached family home situated in an excellent location in the village of Badingham. Offering 6.5 acres gardens and paddocks, this property would be ideal for those with horses or other animals. Accommodation comprises briefly of: • Entrance hall • Six bedrooms • Three reception rooms • Study/workshop • Garden room • Large garage • Car port • Stable block • 6.5 acres gardens and paddocks (STS) The Property The front entrance door welcomes you into the entrance hall of this spacious property, with a cloakroom comprising low level WC and hand wash basin. A further door opens into the kitchen with a range of base and wall units, drawers and worktops, single drainer sink, built-in electric oven and pantry. Across the hallway is the study featuring a range of shelving and desk/work surfaces with cupboards below. Adjacent to the kitchen and study is the generous garden room, with french windows looking out to the rear aspect, sliding patio doors, plumbing and space for washing machine and tumble dryer. The open plan living room and dining room, featuring a stone fireplace with wood burning stove, can be accessed through the kitchen and through the inner hall with stairs leading to the upstairs accommodation. To the right of the landing you will find a bedroom with window to the front aspect, adjacent to this is the generous sized master bedroom featuring built in double wardrobes and en-suite bathroom with shower cubicle, low level WC and hand wash basin. -

Dennington News Issue 24 .April

Dennington News Issue 24: April-June 2021 www.denningtonvillagehall.com The Dennington Queen With longer days, warmer weather, vaccines and restrictions slowly being lifted we are very much looking forward to happier days at The Dennington Queen. We would again like to thank everyone who has supported us during the dark days of winter by buying takeaways, it's kept the business ticking over and almost as importantly has kept Lorna and me sane! The good news is that we will continue with the takeaways until we are able to seat customers indoors. The road map at the time of going to print suggests that date will be Monday 17th May. Although we will be allowed to open and customers able to sit outside from 12th April, due to the unpredictable British weather, we don't really feel this is a viable option for us. Having said that, if it's a glorious spring day between those dates, then do give us a call as we would love to open on the odd day for drinks and light lunches if possible. Please see our website www.thedenningtonqueen.co.uk or our facebook page for the latest updates. Jon & Lorna Reeves EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION Despite a chill in the air, the daffodils are out and a couple of sunny days makes it feel like spring has finally come - so let’s hope for warmer, safer and more sociable days ahead! Things will start to reopen cautiously over the next three months, and by the next issue of the Dennington News I hope we’ll be able to look forward to lots of village events, some of which are previewed in this issue. -

Open Stamp History

SPECIAL STAMP HISTORY The Royal Silver Wedding Issue Date of issue: APRIL 26 1948 Thoughts about stamps for the 1948 Royal Silver Wedding arose after the wedding of Princess Elizabeth on 20 November 1947. The GPO commemorated the wedding with only a special postmark because of lack of time to produce stamps following the announcement on 1 August (nine months was considered necessary). The GPO found itself the target of adverse criticism from the public, Parliament and the press. There was a ‘strong public demand for a British pictorial stamp’ to honour the occasion and there had been a missed opportunity to earn valuable foreign currency, especially dollars, a point reiterated by the Treasury. At the end of November 1947 the Channel Islands Liberation and Olympic Games issues planned for 1948 were already in hand; there was no plan to mark the Royal Silver Wedding of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, or awareness that it required commemoration. However, pressures were being exerted, and senior officials responded quickly. The first discussions were on 25 November, and by 1 December the Board had decided: there would be a 2½d stamp ‘for popular use’ and a £1 stamp (aimed primarily at collectors – ‘a special stamp will earn dollars which only a stiff necked purist would overlook at the present time’); with only five months available, attempts to shorten the design process would be made by utilising (a) designs originally submitted for the projected Edward VIII coronation issue and (b) the photographs of the King and Queen that had featured on their 1937 Coronation stamps; the printing would be by Harrison & Sons Ltd of London and High Wycombe, using the photogravure process of which they had a virtual monopoly; 1 the Council of Industrial Design (CoID) would be asked to nominate one or two artists to collaborate with Harrisons in preparing designs. -

Performing Portraiture: Picturing the Upper-Class English Woman in an Age of Change, 1890–1914 by Susan Elizabeth Slattery

Performing Portraiture: Picturing the Upper-Class English Woman in an Age of Change, 1890–1914 by Susan Elizabeth Slattery A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD Graduate Department of Art History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Susan Elizabeth Slattery 2019 Performing Portraiture: Picturing the Upper-Class English Woman in an Age of Change, 1890–1914 Susan Elizabeth Slattery Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History University of Toronto 2019 Abstract This dissertation examines the use of portraiture by upper-class women of Britain in the period 1890—1914 as a means to redefine gender and class perception and to reposition aristocratic women as nostalgic emblems of a stable past and as symbols of a modern future. Through a range of portraiture practices, upper-class women promoted themselves as a new model for a continuing upper class that fulfilled a necessary social function in the altered circumstances of the new century. The period 1890—1914 was an era of change that challenged the existing social structure in Britain, destabilizing the hereditary entitlement of the ruling class and questioning the continuing role and relevance of the upper class. In the same period, changes in the technology of print and photography meant that, for the first time, there was the ability to disseminate portrait images through mass media on an economical basis, leading to a proliferation of illustrated journals and magazines. These circumstances provided an opportunity for upper-class women to reimagine the social and political potential of portraiture. ii My analysis examines different forms of media through intensive case studies arguing a progression from a traditional static image to a fluid interdisciplinary performative portraiture practice. -

Spring 2010 Spring 2010

SPRING 2010 SPRING 2010 CLEARWATER BOOKS 213b Devonshire Road Forest Hill London SE23 3NJ United Kingdom Telephone: 07968 864791 Email: [email protected] Website: www.clearwaterbooks.co.uk Unless otherwise indicated, all the items in this catalogue are first English editions, published in Greater London. Dust wrappers are mentioned when present (post-1925). Any item found to be unsatisfactory may be returned, but within ten days of receipt, please. Shipping charges are additional. Personal Note Last autumns catalogue was a great experience. Writing it was an enjoyable challenge and then, perhaps imprudently, issuing it amidst the postal strike added an element of tension as I waited a whole twenty-four hours for the telephone to ring, wondering if it could really be so bad as to not generate a single enquiry. Eventually however the calls began, and so did the real fun. Customers I had not spoken to in years, and as often as not never personally dealt with at all, called with the most delightful reminiscences about dad. And the occasional order, of course. Here is the follow-up, my spring 2010 issue (I wonder at what point it stops being presumptive to number them?) The catalogue is divided between literature and a little poetry towards the front; and art and illustrated at the rear, and I do hope it will be an enjoyable read. Clearwater will be exhibiting at the Hand & Flower Hotel book fair in June, now in its third year. If you have the opportunity do come along to peruse the books and say hello Best Wishes Bevis Clarke 1. -

1507: the Well-Dressed Civil Servant. Eddie Marsh, Rupert

C THE WELL- DRESSED CIVIL SERVANT CATALOGUE 1507: MAGGS BROS LTD. Eddie Marsh with Winston Churchill, in 1907. the well-dressed civil servant Rupert Brooke Eddie Marsh Christopher Hassall & their friends Catalogue 1507 MAGGS BROS LTD 48 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DR www.maggs.com +44 (0) 20 3906 7069 An introduction to Edward Marsh This catalogue is from the library of John Schroder. His first purchase of a book by Rupert Brooke was made in Cambridge in 1939, and provided the impetus for the cre- ation of a collection initially focused on Brooke himself, but which soon expanded to include Brooke’s friend and biographer Eddie Marsh, and Marsh’s friend and biogra- pher Christopher Hassall: consequently to a certain extent the collection and catalogue revolves around the figure of Marsh himself, reinforced when Schroder was able to buy all of Brooke’s correspondence to Marsh, now at King’s College Cambridge. Schroder celebrated the collection in the handsome catalogue printed for him by the Rampant Lions Press in 1970. Marsh, the Well-Dressed Civil Servant, was a dapper, puck- ish and popular figure in the drawing rooms of Edwardian and Georgian England. He was very clever and highly edu- cated, well-connected, courteous, amiable and witty, and was a safe single man at a house or dinner party, especially one in need of a tame intellectual. For his part, he loved the mores of the unconventional upper-classes of England, the Barings, Lyttons, Custs, Grenfells and Manners, although he himself was not of the aristocracy, but of “the official class”.