Looking the East End in the Face: the Impact of the British Monarchy on Civilian Morale in the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage Benoît Pelletier* This article examines the constitutional Cet article analyse les implications implications, for Canada and the other members of the constitutionnelles, pour le Canada et les autres pays Commonwealth, of a morganatic marriage in the membres du Commonwealth, d’un mariage British royal family. The Germanic concept of morganatique au sein de la famille royale britannique. “morganatic marriage” refers to a legal union between Le concept de «mariage morganatique», d’origine a man of royal birth and a woman of lower status, with germanique, renvoie à une union légale entre un the condition that the wife does not assume a royal title homme de descendance royale et une femme de statut and any children are excluded from their father’s rank inférieur, à condition que cette dernière n’acquière pas or hereditary property. un titre royal, ou encore qu’aucun enfant issu de cette For such a union to be celebrated in the royal union n’accède au rang du père ni n’hérite de ses biens. family, the parliament of the United Kingdom would Afin qu’un tel mariage puisse être célébré dans la have to enact legislation. If such a law had the effect of famille royale, une loi doit être adoptée par le denying any children access to the throne, the laws of parlement du Royaume-Uni. Or si une telle loi devait succession would be altered, and according to the effectivement interdire l’accès au trône aux enfants du second paragraph of the preamble to the Statute of couple, les règles de succession seraient modifiées et il Westminster, the assent of the Canadian parliament and serait nécessaire, en vertu du deuxième paragraphe du the parliaments of the Commonwealth that recognize préambule du Statut de Westminster, d’obtenir le Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state would be consentement du Canada et des autres pays qui required. -

AN ACCOUNT the Nobler Effects of Real Patriotism

ANTIQUITIES IN FORFARSHIRE. 15 the minutest circumstances which refer to his own country, or to the place of his nativity, but from that love that he bears to his native soil ? The same principle which influences him in these more limited inquiries, will, when a little farther extended, produce AN ACCOUNT the nobler effects of real patriotism. Influenced by this generous principle, individuals are often impelled to more gallant and glorious or actions than could ever have proceeded from a regard to personal fame. The illiterate soldier or seaman, whose name is buried in SOME REMAINS OF ANTIQUITY IN FORFARSHIRE. oblivion, cheerfully consents to this sacrifice, if it be subservient to the honour of his beloved country. It may be said, perhaps, that the study of etymology would be Communicated to the Society by Dr Jamieson. less of a conjectural nature, were it directed by some general rules. In every branch of literature there must be exceptions from these; but, in ordinary cases, they are by no means to be neglected. One thing that should be particularly attended to, in this study, is the THE etymology of the names of places, if not a necessary branch, existing, or the original; language of the country. In consequence is certainly an useful appendage, of history. While it relieves the of disregarding this rule, ingenious men have often bewildered mind of the reader, often fatigued by attending to a narrative that themselves ;in seeking an obscure and uncertain etymon, while in general only exhibits the vices of man, and their fatal effects,—it they rejected that which was most simple and obvious. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

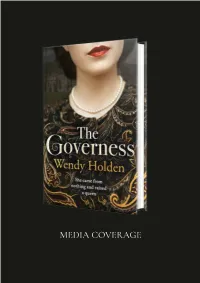

Media Coverage

MEDIA COVERAGE 1 THE GOVERNESS is a novel about the childhood of the Queen and the unknown woman whose unique influence helped make her the world’s most successful monarch. It takes us right to the heart of the Royal Family through a crucial period in history, through the 1936 Abdication, the 1937 Coronation and the whole of World War II. Ending in 1947 with Princess Elizabeth’s wedding, THE GOVERNESS is the prequel to The Crown. Published by Welbeck in AUGUST 2020, it went straight into the Sunday Times bestseller list, earned rave reviews and intense media interest.. 2 SUNDAY TIMES TOP TEN 3 4 FEATURE COVERAGE 5 The Daily Mail Feature Link 6 The Mail on Sunday Feature Link 7 Tatler 8 Tatler Feature Link 9 Harpers Bazaar 10 Sunday Express Magazine 11 Sunday Express Magazine Feature Link 12 Sunday Express Magazine Saga Magazine 13 Saga Magazine People Magazine 14 People Magazine 15 Woman and Home 16 Woman and Home 17 My Weekly Short Story, Fiction Special 18 Daily Telegraph Feature Link 19 BROADCAST COVERAGE 20 BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Interview Feature Link 21 Sky News Interview 22 BBC Culture Piece by Hephzibah Anderson on royalty in fiction, leading with The Governess Feature Link 23 REVIEW COVERAGE 24 Good Housekeeping Bookshelf Top 10 Choice 25 Woman & Home Book Club Choice 26 Daily Mail ‘A hugely entertaining, emotionally satisfying story of love and loyalty.’ 27 My Weekly 28 Mail on Sunday ‘A poignant, fictional reimagining of a woman condemned by history, with plenty of modern-day echoes.’ 29 Platinum Magazine ‘Brilliantly researched.. -

George Bush Presidential Library Records on the Royal Family of the United Kingdom

George Bush Presidential Library 1000 George Bush Drive West College Station, TX 77845 phone: (979) 691-4041 fax: (979) 691-4030 http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu [email protected] Inventory for FOIA Request 2017-1750-F Records on the Royal Family of the United Kingdom Extent 106 folders Access Collection is open to all researchers. Access to Bush Presidential Records, Bush Vice Presidential Records, and Quayle Vice Presidential Records is governed by the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)(5 USC 552 as amended) and the Presidential Records Act (PRA)(44 USC 22) and therefore records may be restricted in whole or in part in accordance with legal exemptions. Copyright Documents in this collection that were prepared by officials of the United States government as part of their official duties are in the public domain. Researchers are advised to consult the copyright law of the United States (Title 17, USC) which governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Provenance Official records of George Bush’s presidency and vice presidency are housed at the George Bush Presidential Library and administered by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). Processed By Staff Archivists, November 2017. Previously restricted materials are added as they are released. System of Arrangement Records that are responsive to this FOIA request were found in five collection areas—Bush Presidential Records: WHORM Subject Files; Bush Presidential Records: Staff and Office Files; Bush Vice Presidential Records: Staff and Office Files; and Quayle Vice Presidential Records: Staff and Office Files. -

“Naughty Willie” at Rhodes House

Gowers of Uganda : Conduct and Misconduct Being an abridged version of an article forthcoming in ARAS : Gowers of Uganda: The Public and Private Life of a Forgotten Colonial Governor Roger Scott, University of Queensland I Apparently, not a lot has been written about the conduct of the private lives of colonial governors. This is in contrast to the information provided in histories and novels and films about white settler society in southern and eastern Africa. In my conference contribution, I want to add to this scarce literature. My forthcoming article in ARAS has a wider compass, including an appreciation of the intersection between the public and private life of a forgotten governor of Uganda, Sir William Gowers. Both pieces draw upon original archival and obscure secondary sources examined in the context of a wider project, a biography by my wife focussed on another member of the Gowers family, her paternal grand-father, Sir Ernest Gowers. These primary sources1 provide testimony from, among others, the Prince of Wales and his aide-de-campe, that Gowers was outgoing, entertaining, and full of bravado as well as personal bravery. The same files also reveal that his personal life became a source of widespread scandal among the East African Europeans, especially missionaries, and it required the intervention of his mentor Lord Lugard to fight off his dismissal by the Colonial Secretary. William was in other words a prototype of the cliché of the romantic literature of his era: the “Black Sheep” of the family. William and his younger brother Ernest were provided with an education at Rugby and Cambridge explicitly designed for entry to the public service. -

World War 11

World War 11 When the British Government declared war against Germany in September 1939, notices went out to many people requiring them to report to recruiting centres for assessment of their fitness to serve in the armed forces. Many deaf men went; and many were rejected and received their discharge papers. Two discharge certificates are shown, both issued to Herbert Colville of Hove, Sussex. ! man #tat I AND NATIOIUL WVlc4 m- N.S. n. With many men called up, Britain was soon in dire need of workers not only to contribute towards the war but to replace men called up by the armed forces. Many willing and able hands were found in the form of Deaf workers. While many workers continued in their employment during the war, there were many others who were requisitioned under Essential Works Orders (EWO) and instructed to report to factories elsewhere to cany out work essential to the war. Deaf females had to do ammunition work, as well as welding and heavy riveting work in armoury divisions along with males. Deaf women were generally so impressive in their war work that they were in much demand. Some Deaf ladies were called to the Land Army. Carpenters were also in great demand and they were posted all over Britain, in particular in naval yards where new ships were being fitted out and existing ships altered for the war. Deaf tailors and seamstresses were kept busy making not only uniforms and clothing materials essential for the war, but utility clothes that were cheaply bought during the war. -

Memories Come Flooding Back for Ogs School’S Last Link with Headingley

The magazine for LGS, LGHS and GSAL alumni issue 08 autumn 2020 Memories come flooding back for OGs School’s last link with Headingley The ones to watch What we did Check out the careers of Seun, in lockdown Laura and Josh Heart warming stories in difficult times GSAL Leeds United named celebrates school of promotion the decade Alumni supporters share the excitement 1 24 News GSAL launches Women in Leadership 4 Memories come flooding back for OGs 25 A look back at Rose Court marking the end of school’s last link with Headingley Amraj pops the question 8 12 16 Amraj goes back to school What we did in No pool required Leeds United to pop the question Lockdown... for diver Yona celebrates Alicia welcomes babies Yona keeping his Olympic promotion into a changing world dream alive Alumni supporters share the excitement Welcome to Memento What a year! I am not sure that any were humbled to read about alumnus John Ford’s memory and generosity. 2020 vision I might have had could Dr David Mazza, who spent 16 weeks But at the end of 2020, this edition have prepared me for the last few as a lone GP on an Orkney island also comes at a point when we have extraordinary months. Throughout throughout lockdown, and midwife something wonderful to celebrate, the toughest school times that Alicia Walker, who talks about the too - and I don’t just mean Leeds I can recall, this community has changes to maternity care during 27 been a source of encouragement lockdown. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860- 1901 Charles Vincent Reed, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Richard Price Department of History ABSTRACT: The dissertation explores the development of global identities in the nineteenth-century British Empire through one particular device of colonial rule – the royal tour. Colonial officials and administrators sought to encourage loyalty and obedience on part of Queen Victoria’s subjects around the world through imperial spectacle and personal interaction with the queen’s children and grandchildren. The royal tour, I argue, created cultural spaces that both settlers of European descent and colonial people of color used to claim the rights and responsibilities of imperial citizenship. The dissertation, then, examines how the royal tours were imagined and used by different historical actors in Britain, southern Africa, New Zealand, and South Asia. My work builds on a growing historical literature about “imperial networks” and the cultures of empire. In particular, it aims to understand the British world as a complex field of cultural encounters, exchanges, and borrowings rather than a collection of unitary paths between Great Britain and its colonies. ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860-1901 by Charles Vincent Reed Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Advisory Committee: Professor Richard Price, Chair Professor Paul Landau Professor Dane Kennedy Professor Julie Greene Professor Ralph Bauer © Copyright by Charles Vincent Reed 2010 DEDICATION To Jude ii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS Writing a dissertation is both a profoundly collective project and an intensely individual one. -

The Three Little Princesses Free

FREE THE THREE LITTLE PRINCESSES PDF Georgie Adams,Emily Bolam,Adjoa Andoh | none | 20 Sep 2007 | Hachette Children's Group | 9780752886626 | English | London, United Kingdom The 3 Little Princesses Episode 1 - video dailymotion The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item The Three Little Princesses its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. About this product. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where The Three Little Princesses is applicable. Will be clean, not soiled or stained. Books will be free of page markings. See all 4 brand new listings. Buy It Now. Add to cart. About this product Product Identifiers Brand. Show More Show Less. Any Condition Any Condition. See all 7 - All listings for this product. No ratings or reviews yet No ratings or reviews yet. Be the first to write a review. You may also like. Reader's Digest Magazines. Little Golden Books. Douglas Adams Books. Phonics Practice Readers. Reader's Digest Books. This item doesn't belong on this page. Be the first to write a review About this product. Early Reader: The Three Little Princesses by Georgie Adams | Hachette UK Originally published inThe Little Princesses was the first account of British Royal life inside Buckingham Palace as revealed by The Three Little Princesses Crawford, who served as governess to princesses Elizabeth and Margaret. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British-Free French Relations 1940-1941" (2019)

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2019 Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British- Free French Relations 1940-1941 Samantha Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Sullivan, Samantha, "Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British-Free French Relations 1940-1941" (2019). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 324. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/324 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British-Free French Relations 1940-1941 By: Samantha Sullivan Advised by: Drs. Steven Zdatny, Andrew Buchanan, and Meaghan Emery University of Vermont History Department Honors College Thesis April 17, 2019 Acknowledgements: Nearly half of my time at UVM was spent working on this project. Beginning as a seminar paper for Professor Zdatny’s class in Fall 2018, my research on Churchill and De Gaulle slowly grew into the thesis that follows. It was a collaborative effort that allowed me to combine all of my fields of study from my entire university experience. This project took me to London and Cambridge to conduct archival research and made for many late nights on the second floor of the Howe Library. I feel an overwhelming sense of pride and accomplishment for this thesis that is reflective of the work I have done at UVM.