Colman Dock Environmental Assessment Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As a DiErent Route Through Downtown Buses Continuing INTERBAY Swedish S

N 152 St to Shoreline CC Snohomish County– to Aurora toAuroraVill toMtlk to Richmond NE 150 St toWoodinvilleviaBothell 373 5 SHORELINE 355 Village Beach Downtown Seattle toNSt Terr to Shoreline CC toUWBothell 308 512 402 405 410 412 347 348 77 330 309 toHorizonView 312 413 415 416 417 421 NE 145 St 373 308 NE 145 St toKenmoreP&R N 145 St 304 316 Transit in Seattle 422 425 435 510 511 65 308 toUWBothell 513 Roosevelt Wy N Frequencies shown are for daytime period. See Service Guide N 143 St 28 Snohomish County– 346 512 301 303 73 522 for a complete summary of frequencies and days of operation. 5 64 University District 5 E 304 308 For service between 1:30–4:30 am see Night Owl map. 512 810 821 855 860 E N 871 880 y 3 Av NW 3 Av Jackson Park CEDAR W Frequent Service N 135 St Golf Course OLYMPIC y Linden Av N Linden Av PARK t Bitter i Every 15 minutes or better, until 7 pm, Monday to Friday. C HILLS weekdays Lake e 372 Most lines oer frequent service later into the night and on NW 132 St Ingraham k a Ashworth Av N Av Ashworth N Meridian Av NE 1 Av NE 15 Av NE 30 Av L weekends. Service is less frequent during other times. (express) 373 77 N 130 St Roosevelt Wy NE 372 weekends 28 345 41 Link Light Rail rapid transit North- every 10 minutes BITTER LAKE acres 8 Av NW 8 Av Park 5 NW 125 St N 125 St Haller NE 125 St E RapidRide limited stop bus for a faster ride 345 Lake NE 125 St every 10–12 minutes 346 PINEHURST 8 Frequent Bus every 10–12 minutes BROADVIEW 99 347 348 continues as LAKE CITY 75 Frequent Bus every 15 minutes 41 345 NE 120 St Northwest -

MHMP Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 September 2019 Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan 21 MHMP December 2019 Kitsap County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan (MHMP) 2019 • 1 This page intentionally left blank. Kitsap County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan (MHMP) 2019 • i This page intentionally left blank. Kitsap County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan (MHMP) 2019 • iii Table of Contents COUNCIL RESOLUTION .......................................................................................................... II RECORD OF CHANGES ........................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 THE PLANNING PROCESS .....................................................................................................11 Mitigation Planning Defined ...................................................................................................11 Lead Agency and Stakeholder Steering Committee Participation ..........................................12 Hazard Identification & Vulnerability Analysis (HIVA) Process ...............................................21 Hazard Mitigation Process for Kitsap County .........................................................................23 Public Outreach & Engagement.............................................................................................28 -

WADOT Seattle Multimodal 2018 IHA Application

Request for an Incidental Harassment Authorization under the Marine Mammal Protection Act Seattle Multimodal Project at Colman Dock Year 2 Construction 2018-19 Washington State Department of Transportation Ferries Division May 2018 Submitted To: National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Protected Resources 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-3226 Prepared By: Washington State Ferries Richard D. Huey 2901 Third Avenue, Suite 500 Seattle, Washington 98121-3014 206-515-3721 [email protected] Cover: Southern Resident Killer Whales with Seattle skyline (October 2013) (NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Candace Emmons) Table of Contents 1.0 Description of the Activity .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Project Setting and Land Use ................................................................................ 2 1.3 Project Description ................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Regulatory Background ......................................................................................... 5 1.5 In-water Construction Details ................................................................................ 6 1.6 Pile Driving and Removal Techniques................................................................... 8 1.6.1 Vibratory Hammer Driving and Removal .............................................................. -

Bridge the Sound, the Alki–Manchester Ferry by Phillip H

Bridge the Sound, The Alki–Manchester Ferry by Phillip H. Hoffman [email protected] (Note to the Reader: Alki designates a geographic area facing Elliott Bay and Puget Sound located on the northwest corner of the Duwamish Peninsula (location map – Appendix A). A feature of Alki is Alki Point, the western most land projection of the Alki area into Puget Sound.) Overview The Alki-Manchester Ferry served cross-sound automobile and passenger traffic from April 12, 1925 until January 13, 1936. The ferry’s Alki dock was located at 3001 Alki Avenue adjacent to the Alki Beach Park. The ferry was a venture of Harry W. Crosby. Crosby operated the ferry for thirteen months before selling it to the Puget Sound Navigation Company operators of the Black Ball Line ferry fleet and service. In the midst of turbulent Great Depression labor strife, the Black Ball Line bought out its cross-sound ferry competitor, Kitsap County Transportation Company, and achieved a monopoly on Seattle and environs ferry service. The Black Ball Line then eliminated the Alki-Manchester ferry offering. Failure of labor to demand minimum levels of ferry sailings, hence the total availability of work and job security, hastened the Alki ferry’s demise. If the Alki ferry had survived and prospered from Seattle’s growing economy, the Alki neighborhood environmental quality and Alki Beach Park would have become endangered by an expanding dock and automobile traffic, congestion and parking demands. The festive dock opening dedication of April 1925 would have given way to a late twentieth century urban misery. Introduction This paper is the first of a three-part series about transportation improvements that if they had not failed or been discontinued would have forever changed Alki’s character – for the worse. -

MMPA IHA For

Request for an Incidental Harassment Authorization under the Marine Mammal Protection Act Seattle Multimodal Project at Colman Dock Year 4 Construction 2020-21 Washington State Department of Transportation Ferries Division April 21, 2020 Submitted To: National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Protected Resources 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-3226 Prepared By: Washington State Ferries Richard D. Huey 2901 Third Avenue, Suite 500 Seattle, Washington 98121-3014 206-515-3721 [email protected] Cover: California Sea Lion hauled out on Colman construction platform (WSDOT 2018). Table of Contents 1.0 Description of the Activity .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Project Setting and Land Use ................................................................................ 2 1.3 Project Description ................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Regulatory Background ......................................................................................... 5 1.5 In-water Construction Details ................................................................................ 6 1.6 Pile Driving and Removal Techniques................................................................... 8 1.6.1 Vibratory Hammer Driving and Removal .............................................................. -

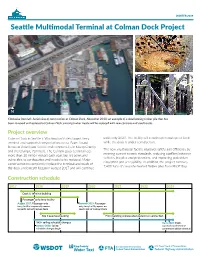

Seattle Multilmodal Terminal at Colman Dock

WINTER 2019 Seattle Multimodal Terminal at Colman Dock Project N Clockwise from left: Aerial view of construction at Colman Dock, November 2018; an example of a deteriorating timber pile that has been removed and replaced at Colman Dock; existing timber trestle will be replaced with new concrete and steel trestle. Project overview Colman Dock in Seattle is Washington State’s largest ferry until early 2023. The facility will remain open and operational terminal and supports transportation across Puget Sound while the dock is under construction. between downtown Seattle and communities in Kitsap County The new, multimodal facility improves safety and efficiency by and the Olympic Peninsula. The Colman Dock terminal sees meeting current seismic standards, reducing conflicts between more than 10 million visitors each year, but it’s aging and vehicles, bicycles and pedestrians, and improving pedestrian vulnerable to earthquakes and needs to be replaced. Major circulation and accessibility. In addition, the project removes construction to completely replace the terminal and much of 7,400 tons of creosote-treated timber piles from Elliott Bay. the dock underneath began in August 2017 and will continue Construction schedule 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Dock & terminal building Passenger-only ferry facility August 2017: Passenger-only Summer 2019: Passenger- ferry facility temporarily moves only ferry facility opens on to north side of Colman Dock south side of Colman Dock Slip 3 overhead loading Entry building and elevated pedestrian connecti on WSF sailing schedule changes Early 2023: Public January 2018: Sailing outreach to determine schedule changes begin permanent sailing schedule U.S. Department of Transportation Water Taxi FTA Federal Transit Administration How to get to the Seattle Ferry Terminal 3rd Ave Riding a bicycle onto the ferry DOWNTOWN Water Taxi and Fast SEATTLE Ferries dock 2nd Ave People biking may enter the terminal using one of two entrances located near Yesler Way. -

2016 Pioneer Square Visitor Map and Guide

WELCOME WHERE IS PIONEER SQUARE? Glad you asked. Pioneer Square is located just south of downtown and is the heart and DOWNTOWN soul of Seattle’s Historic District. You’ll find it SEATTLE surrounded by: • Retail core to the north • Chinatown-International District to the east • Stadium District and SODO to the south • Central Waterfront to the west FRONT R PIONEER SQUARE WATE CHINATOWN INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT If you’re the explorer type, you’re in luck. Pioneer Square is centrally located to more modes of public transit than anywhere else in the city. A ferry, water taxi, streetcar, train, or bus is never more than a few steps away. If you’re biking, take advantage of the protected bike lane on Second Avenue that traverses downtown. If you’re headed to or from Sea-Tac International Airport, you can just jump on the Sound Transit Link SODO Light Rail. Quick and easy. And if you’re driving, it’s easily accessible from Interstate 5 and 90, as well as Highway 99. See the Getting Here section in this guide for more transportation options. 2 HISTORIC DOWNTOWN TAKE A WALK BACK 160 YEARS INTO THE PAST Okay, so Seattle is known for its rain. There, we said it. But imagine what it was like in 1852. For the original residents of Seattle, it was bitterly cold. After a winter spent at Alki Beach, they’d had enough. They moved across the water and settled Pioneer Square with the same entrepreneurial spirit that still lives on today. Arthur Denny, “Doc” Maynard, and Henry Yesler, who owned the lumber mill at the end of Skid Road, set to work building the future of Seattle. -

Waterfront - Main Corridor

APPROVED MEETING MINUTES December 7 & 8, 2017 Commission Waterfront - Main Corridor Commissioners Present Commissioners Excused Jenny A. Durkan Ross Tilghman, Chair Ben de Rubertis Mayor John Savo, Vice Chair Evan Fowler Samuel Assefa Lee Copeland Director, OPCD Thaddeus Egging Rachel Gleeson Laura Haddad Brianna Holan Ross Tilghman, Chair Rick Krochalis John Savo, Vice Chair Project Description The Office of the Waterfront has developed a detailed design for the Alaskan Lee Copeland Way street designs between King and Bell Streets. The proposal includes design elements that will span the entire corridor as well as design elements that are Ben de Rubertis unique to the following places along Alaskan Way: • Pioneer Square Thaddeus Egging • Colman Dock Mobility Hub Rachel Gleeson • Historic Piers • Central Public Space Laura Haddad • Pike & Pine Streets • Belltown Brianna Holan Under the proposal, Alaskan Way would include four lanes in each direction Rick Krochalis from S King St to Yesler Way and narrow to two lanes in each direction north of Yesler Way. The intersection of Yesler Way and Alaskan Way would include Evan Fowler additional turn lanes for traffic heading to Colman Dock, serving the Washington State Ferries. North of University St, both Alaskan Way and Elliott Ave would include two general purpose lanes in each direction. Turn lanes would widen Michael Jenkins the Pine St intersection as the right-of-way changes from Alaskan Way to Elliott Director Ave heading north to Belltown. Each segment will include continuous sidewalks, Valerie Kinast a cycle track, a planted median, and planted buffers between the road and the Coordinator sidewalk. -

Stranded at the Dock? Integrating Passenger-Only Ferry Service Into the Regional Transportation Network

Stranded at the Dock? Integrating Passenger-Only Ferry Service Into the Regional Transportation Network Jessyn Schor Sara Longley WashPIRG Foundation November 2004 1 Acknowledgements The WashPIRG Foundation gratefully acknowledges Dick Hayes (Kitsap Transit), Cathy Knox-Browing (Kitsap Transit), Doug Johnson (Kitsap Transit), and Gregory Dronkert for providing valuable information for this report. Special thanks to Ann Sutphin (City of Seattle) and Dick Hayes (Kitsap Transit) for peer review. Thanks also to Robert Pregulman for editorial assistance. Thanks to Sabiha Basrai for cover design. Cover photograph courtesy of Steven Brown. The authors alone bear any responsibility for factual errors. The recommendations are those of the WashPIRG Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders. © 2004 WashPIRG Foundation The WashPIRG Foundation is a 501(c)(3) organization working on environmental protection, consumer rights, and good government in Washington. For additional copies of this report, send $10 (including shipping) to: WashPIRG Foundation 3240 Eastlake Ave. E, #100 Seattle, WA 98102 For more information about the WashPIRG Foundation, please call (206) 568-2850 or visit the WashPIRG website at www.washpirg.org. 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 A Ferry System in Crisis 6 Fares Increased and Service Cut Back 7 Passenger-Only Ferry Service Hit Especially Hard 8 Private Operators Step In 9 Bremerton’s Kitsap Ferry Company 9 Kingston’s Aqua Express 11 Improving Commute Options? 12 Bremerton 12 Kingston 13 Seattle 13 Smart Card 15 Integrating Passenger-Only Ferry Service 16 Bremerton 16 Kingston 17 Seattle 18 Conclusion and Recommendations 19 3 Stranded at the Dock? Integrating Passenger-Only Ferry Service Into the Regional Transportation Network Executive Summary Washington’s ferry system is in crisis. -

Hazard Ldentification &

Hazard ldentification & Vu I nerabi I ity Assessment This page intentionally left blank. Kitsap County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan (MHMP) 2019 Table of Gontents lntroduction .1 Gounty & Gity Profiles .2 Kitsap County....... ..3 Bainbridge lsland 26 Bremerton 3B Port Orchard ............... 38 Poulsbo 54 Natural Hazards 62 Droughts 64 Earthquakes................ 70 Floods 70 Forest & Urban Fires.......... ..86 Landslides & Erosion 106 Severe Storms/Tornadoes 116 Tsunamis, High Waves, & Seiches ............... 122 Volcanic Ash Fall..... 132 Technological Hazards & Human-Caused Threats... 136 Cybersecurity.............. 138 Dam Fai1ure ............... 140 Energy Emergency 144 Hazardous Sites/Materials ............ 148 Radiological Emergencies............. ,154 Search & Rescue Emergencies................ 156 Terrorism 158 Transportation Mass Casualty lncident 160 Epidemics (Human & Animal)... .164 References & Authorities 172 Kitsap County Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan (MHMP) 2019 ii Tables & Figures Table 1: Definitions ............... ...........2 Table 2: HIVA 2019 Ratin9s................ ............... 5 Table 3: Risk Rating Adjective Descriptions............... .......... 8 Table 4: Kitsap County Most Recent Population Estimates ....................4 Table 5: Civilian Labor Force, 2017 Estimates (US Census) ..................7 Table 6: Nonfarm lndustry Employment................ ...............7 Table 7: School District Attendance,20lO Estimates (US Census).............. .,..........7 Table 8: lndian Nations, 2019 Esri Demographics............ -

Kitsap Transit, King County Marine Division Partner to Launch Fast-Ferry

JOINT PRESS RELEASE Kitsap Transit, King County Marine Division work together to launch fast-ferry service between Kitsap Peninsula and downtown Seattle January 18, 2017 Contact for Kitsap Transit: Sanjay Bhatt, Kitsap Transit PIO 360-824-4926, [email protected] Contact for King County Marine Division: Brent Champaco, King County DOT PIO 206-477-9094, [email protected] SEATTLE – King County Executive Dow Constantine welcomed elected officials from Kitsap County today at Colman Dock in Seattle after the ceremonial first sailing of Kitsap Transit’s fast ferry, setting the stage for the launch of fast-ferry service this summer between Bremerton and downtown Seattle. Just before 11 a.m. today, Constantine welcomed Bremerton Mayor Patty Lent and Kitsap Transit Board Chair Rob Putaansuu to Seattle as their Kitsap County delegation arrived on the Rich Passage 1. The 118- passenger foil-assisted catamaran is the first of six Kitsap Transit vessels envisioned to support fast-ferry service on three routes between the Kitsap Peninsula and downtown Seattle. In November, Kitsap County voters approved a local sales-tax increase to support fast ferries. Since then, Kitsap Transit has been working to develop an agreement with King County Marine Division to operate and maintain the Rich Passage 1 and future vessels. Both parties anticipate their legislative bodies will execute an agreement in the spring. “King County Marine Division has demonstrated its expertise through its operation of the King County Water Taxi and has the marine infrastructure to support passenger-only ferry services,” said Putaansuu, who is also Port Orchard’s mayor. “With a strong operating partner, Kitsap Transit can continue to deliver reliable service to our commuter base and usher in a new chapter for inter-county transit in Kitsap County.” The King County Water Taxi connects West Seattle and Vashon Island to the Seattle waterfront and hit a new record for ridership in 2016. -

The Mosquito Fleet Trail Master Plan

The Mosquito Fleet Trail Master Plan Prepared for Kitsap County Department of Public Works, August 2001 The Mosquito Fleet Trail Master Plan Prepared for Kitsap County Department of Public Works Prepared by MacLeod Reckord Marcia Sinclair Adolfson Associates August 2001 Acknowledgements Jeannie Schultze, Central Kitsap School District Dr. Carol Whitehead, Superintendent, Bremerton School District This plan would not have been possible without the assistance of a great number Jerry Wilson, South Kitsap School District of individuals. We wish to thank the following people for their time and input: Roy Devore, South Kitsap School District Kitsap County City of Bremerton Chris Gears, (former) Bremerton Parks and Recreation Director Kitsap County Commissioners Randy Witt, (former) Bremerton City Engineer Chris Endresen, North District Jan Angel, South District Charlotte Garrido, (former) South District City of Port Orchard Tim Botkin, Central District Donna Gross, (former) City Planner Larry Curles, Port Orchard Public Works Kitsap County Public Works Randy Casteel, Director Bill Zupancic, Project Manager City of Poulsbo Doug Bear, Public Information Programs Supervisor Mary McCluskey, Poulsbo Parks Director Lisa Moses, Public Works Systems Coordinator John Stephenson, City Engineer Cindy Keiser, Staff Kitsap County Department of Community Development Suquamish Tribe Jason Rice, Planner Peggy Deam, Cultural Development Jerry Harless, (former) GIS Manager Scott Kroll, Planning Director Steve Schunzel, GIS Manager Rick Kimball, SEPA Coordinator Organizations/Businesses Kitsap County Department of Parks and Recreation Bainbridge Island Bicycle Joseph Coppo, Open Space Coordinator Bremerton Chamber of Commerce Bremerton Naval Museum Kitsap County Port Districts Horluck Transportation Company, Inc. Port of Bremerton Kingston Classic Cycle Port of Brownsville Kingston Greater Community Chamber of Commerce Port of Kingston Kitsap County Historical Society Museum Port of Poulsbo Kitsap Key and Bike Shop Port of Silverdale Missing Link Cycles, Inc.