On the Bryogeography of Western Melanesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Southwest Pacific: U.S

Order Code RL34086 The Southwest Pacific: U.S. Interests and China’s Growing Influence July 6, 2007 Thomas Lum Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Bruce Vaughn Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division The Southwest Pacific: U.S. Interests and China’s Growing Influence Summary This report focuses on the 14 sovereign nations of the Southwest Pacific, or Pacific Islands region, and the major external powers (the United States, Australia, New Zealand, France, Japan, and China). It provides an explanation of the region’s main geographical, political, and economic characteristics and discusses United States interests in the Pacific and the increased influence of China, which has become a growing force in the region. The report describes policy options as considered at the Pacific Islands Conference of Leaders, held in Washington, DC, in March 2007. Although small in total population (approximately 8 million) and relatively low in economic development, the Southwest Pacific is strategically important. The United States plays an overarching security role in the region, but it is not the only provider of security, nor the principal source of foreign aid. It has relied upon Australia and New Zealand to help promote development and maintain political stability in the region. Key components of U.S. engagement in the Pacific include its territories (Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa), the Freely Associated States (Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau), military bases on Guam and Kwajalein atoll (Marshall Islands), and relatively limited aid and economic programs. Some experts argue that U.S. involvement in the Southwest Pacific has waned since the end of the Cold War, leaving a power vacuum, and that the United States should pay greater attention to the region and its problems. -

Systematic Studies on Bryophytes of Northern Western Ghats in Kerala”

1 “Systematic studies on Bryophytes of Northern Western Ghats in Kerala” Final Report Council order no. (T) 155/WSC/2010/KSCSTE dtd. 13.09.2010 Principal Investigator Dr. Manju C. Nair Research Fellow Prajitha B. Malabar Botanical Garden Kozhikode-14 Kerala, India 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to Dr. K.R. Lekha, Head, WSC, Kerala State Council for Science Technology & Environment (KSCSTE), Sasthra Bhavan, Thiruvananthapuram for sanctioning the project to me. I am thankful to Dr. R. Prakashkumar, Director, Malabar Botanical Garden for providing the facilities and for proper advice and encouragement during the study. I am sincerely thankful to the Manager, Educational Agency for sanctioning to work in this collaborative project. I also accord my sincere thanks to the Principal for providing mental support during the present study. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. K.P. Rajesh, Asst. Professor, Zamorin’s Guruvayurappan College for extending all help and generous support during the field study and moral support during the identification period. I am thankful to Mr. Prasobh and Mr. Sreenivas, Administrative section of Malabar Botanical Garden for completing the project within time. I am thankful to Ms. Prajitha, B., Research Fellow of the project for the collection of plant specimens and for taking photographs. I am thankful to Mr. Anoop, K.P. Mr. Rajilesh V. K. and Mr. Hareesh for the helps rendered during the field work and for the preparation of the Herbarium. I record my sincere thanks to the Kerala Forest Department for extending all logical support and encouragement for the field study and collection of specimens. -

Flora of New Zealand Mosses

FLORA OF NEW ZEALAND MOSSES BRACHYTHECIACEAE A.J. FIFE Fascicle 46 – JUNE 2020 © Landcare Research New Zealand Limited 2020. Unless indicated otherwise for specific items, this copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence Attribution if redistributing to the public without adaptation: "Source: Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research" Attribution if making an adaptation or derivative work: "Sourced from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research" See Image Information for copyright and licence details for images. CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Fife, Allan J. (Allan James), 1951- Flora of New Zealand : mosses. Fascicle 46, Brachytheciaceae / Allan J. Fife. -- Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, 2020. 1 online resource ISBN 978-0-947525-65-1 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-478-34747-0 (set) 1. Mosses -- New Zealand -- Identification. I. Title. II. Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. UDC 582.345.16(931) DC 588.20993 DOI: 10.7931/w15y-gz43 This work should be cited as: Fife, A.J. 2020: Brachytheciaceae. In: Smissen, R.; Wilton, A.D. Flora of New Zealand – Mosses. Fascicle 46. Manaaki Whenua Press, Lincoln. http://dx.doi.org/10.7931/w15y-gz43 Date submitted: 9 May 2019 ; Date accepted: 15 Aug 2019 Cover image: Eurhynchium asperipes, habit with capsule, moist. Drawn by Rebecca Wagstaff from A.J. Fife 6828, CHR 449024. Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................................................1 Typification...............................................................................................................................................1 -

NEW DATA ABOUT MOSSES on the SVALBARD GLACIERS Olga

NEW DATA ABOUT MOSSES ON THE SVALBARD GLACIERS Olga Belkina Polar-Alpine Botanical Garden-Institute, Kola Science Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Apatity, Murmansk Province, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] Rapid melting and retreat of glaciers in the Arctic is a cause of sustainable long‐ In Svalbard moss populations were found on 9 glaciers. In 2012, during re‐examination of the populations a few term existence of ablation zone on them. Sometimes these areas are the habitats In 2007 B.R.Mavlyudov collected one specimen on individuals of Bryum cryophilum Mårtensson and some plants of some mosses partly due to good availability of water and cryoconite Bertilbreen (Paludella squarrosa (Hedw.) Brid.) and of Sanionia uncinata were found among H. polare shoots in substratum. 14 species were found in this unusual habitat on Alaska and Iceland: some specimens on Austre Grønfjordbreen (Ceratodon some large cushions. Therefore the next stage of cushion Andreaea rupestris Hedw., Ceratodon purpureus (Hedw.) Brid., Ditrichum purpureus (Hedw.) Brid., Warnstorfia sarmentosa succession had begun –emergence of a di‐ and multi‐species flexicaule (Schwaegr.) Hampe, Pohlia nutans (Hedw.) Lindb., Polytrichum (Wahlenb.) Hedenäs, Sanionia uncinata (Hedw.) community. A similar process was observed earlier on the juniperinum Hedw. (Benninghoff, 1955), Racomitrium fasciculare (Hedw.) Brid. Loeske, Hygrohypnella polare (Lindb.) Ignatov & bone of a mammal that was lying on the same glacier. (=Codriophorus fascicularis (Hedw.) Bendarek‐Ochyra et Ochyra) (Shacklette, Ignatova.). Ceratodon purpureus settled in center of almost spherical 1966), Drepanocladus berggrenii (C.Jens.) Broth. (Heusser, 1972), Racomitrium In 2009 populations of two latter species were studied cushion of Sanionia uncinata on the both butt‐ends of the crispulum var. -

New National and Regional Bryophyte Records, 63

Journal of Bryology ISSN: 0373-6687 (Print) 1743-2820 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjbr20 New national and regional bryophyte records, 63 L. T. Ellis, O. M. Afonina, I. V. Czernyadjeva, L. A. Konoreva, A. D. Potemkin, V. M. Kotkova, M. Alataş, H. H. Blom, M. Boiko, R. A. Cabral, S. Jimenez, D. Dagnino, C. Turcato, L. Minuto, P. Erzberger, T. Ezer, O. V. Galanina, N. Hodgetts, M. S. Ignatov, A. Ignatova, S. G. Kazanovsky, T. Kiebacher, H. Köckinger, E. O. Korolkova, J. Larraín, A. I. Maksimov, D. Maity, A. Martins, M. Sim-Sim, F. Monteiro, L. Catarino, R. Medina, M. Nobis, A. Nowak, R. Ochyra, I. Parnikoza, V. Ivanets, V. Plášek, M. Philippe, P. Saha, Md. N. Aziz, A. V. Shkurko, S. Ştefănuţ, G. M. Suárez, A. Uygur, K. Erkul, M. Wierzgoń & A. Graulich To cite this article: L. T. Ellis, O. M. Afonina, I. V. Czernyadjeva, L. A. Konoreva, A. D. Potemkin, V. M. Kotkova, M. Alataş, H. H. Blom, M. Boiko, R. A. Cabral, S. Jimenez, D. Dagnino, C. Turcato, L. Minuto, P. Erzberger, T. Ezer, O. V. Galanina, N. Hodgetts, M. S. Ignatov, A. Ignatova, S. G. Kazanovsky, T. Kiebacher, H. Köckinger, E. O. Korolkova, J. Larraín, A. I. Maksimov, D. Maity, A. Martins, M. Sim-Sim, F. Monteiro, L. Catarino, R. Medina, M. Nobis, A. Nowak, R. Ochyra, I. Parnikoza, V. Ivanets, V. Plášek, M. Philippe, P. Saha, Md. N. Aziz, A. V. Shkurko, S. Ştefănuţ, G. M. Suárez, A. Uygur, K. Erkul, M. Wierzgoń & A. Graulich (2020): New national and regional bryophyte records, 63, Journal of Bryology, DOI: 10.1080/03736687.2020.1750930 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03736687.2020.1750930 Published online: 18 May 2020. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) ,, l • ...J ..... The Disjunct Bryophyte Element of the Gulf of St. Lawrence Region: Glacial and Postglacial Dispersal and Migrational Histories By @Rene J. Belland B.Sc., M.Sc. A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biology Memorial University of Newfoundland December, 1Q84 St. John's Newfoundland Abstract The Gulf St. Lawrence region has a bryophyte flora of 698 species. Of these 267 (38%) are disjunct to this region from western North America, eastern Asia, or Europe. The Gulf of St. Lawrence and eastern North American distributions of the disjuncts were analysed and their possible migrational and dispersal histories during and after the Last Glaciation (Wisconsin) examined. Based on eastern North American distribution patterns, the disjuncts fell into 22 sub elements supporting five migrational/ dispersal histories or combinations of these : (1) migration from the south, (2) migration from the north, (3) migration from the west, (4) survival in refugia, and (5) introduction by man. The largest groups of disjuncts had eastern North American distributions supporting either survival of bryophytes in Wisconsin ice-free areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence or postglacial migration to the Gulf from the south. About 26% of the disjuncts have complex histories and their distributions support two histories. These may have migrated to the Gulf from the west and/or north, or from the west and/or survived glaciation in Gulf ice-free areas. -

Hawaiian Moss Names Bartram (1933) Did Not Include Hawaiian Names in His Manual of Hawaiian Mosses

Hawaiian Moss Names Bartram (1933) did not include Hawaiian names in his manual of Hawaiian mosses. The Hawaiian dictionary by Pukui & Elbert (1986) lists two general terms for mosses, limu and huluhulu, and names for specific types of mosses and liverworts. Unfortunately, only one of these specific names has a scientific name attached to it, Thuidium hawaiiense (now T. cymbifolium). The rest are orphan names that cannot be attached to known species unless other records can be found. A dictionary of modern Hawaiian by Komike Hua`olelo (2003) lists another general term, mākōpi`i, and one specific term hulu pō`ē`ē for Sphagnum moss. Table 10. Known Hawaiian words for mosses, liverworts, and a lichen. Hawaiian English definition `ekaha a moss growing on rotted trees, also limu `ekaha hini hini `ula an upland moss huluhulu a Ka`au hele moa a moss said to grow only in Palolo Valley, Honolulu, named for Ka`au- hele-moa a legendary cock defeated in battle by a hen. She pulled his feathers which became this moss. It is used in leis. hulu pō`ē`ē Sphagnum huluhulu kinds of seaweeds and mosses huluhulu a `īlio a green, velvety carpet-like mountain moss. The spore cases rise above the plants. Lit. fur like a dog. iliohe a name reported for a green freshwater moss kala maka pi`i same as mākole mākō pi`i and kale maka pi`i kalau ipo a moss found in water kale maka pi`i variant of kala maka pi`i, a moss lī pepei ao 1. a seaweed 2. -

Pacific Islander Migration to Australia: the 1980S and Beyond’ Christine Mcmurray and David Lucas

Pacific islander migration to Australia: the 1980s and beyond’ Christine McMurray and David Lucas The 1981 Census of Australia counted 34,826 sume that a large proportion of those in the persons born in Melanesia and Polynesia; by category 0-4 years were residents. 1986 this figure had increased by 39 per cent to Most of the Papua New Guinea-born are 48,536. Prior to 1981 those born in Papua New children of Australians or others born outside Guinea were not distinguished from Papua New Guinea. Connel12 estimated that Australians in the census. However, if the only about 10 per cent were Papua New Papua New Guinea-born are excluded from the Guinea nationals in 1981. In 1986 only 12 per figures for 1981 and 1986 the increase is even cent did not have Australian citizenship, and more striking. In 1976 there were 9663 Pacific- hence could have been Papua New Guinea na- born (including the catch-all category ‘Other tionals. Similarly, many migrants born in New Oceania’but excluding Papua New Guinea and Caledonia, where the Melanesian Kanaks are New Zealand). By 1981 there were 16,129 from now in the minority, could be children of Melanesia and Polynesia alone, and by 1986 French settlers. However, most of those born in there were 27,185; an increase of more than other Pacific states can be assumed to be of 180 per cent in the ten-year period. This paper Polynesian, Melanesian, Indo-Fijian or considers the implications of this change and Micronesian descent. In Fiji, the Melanesians whether migration from this source can be ex- are predominantly Christian, compared with pected to accelerate or decelerate in the next only a small percentage of the Indo-Fijians. -

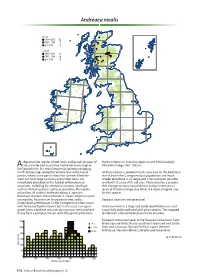

Andreaea Nivalis

Andreaea nivalis Britain 1990–2013 12 1950–1989 7 pre-1950 4 Ireland 1990–2013 0 1950–1989 0 pre-1950 0 characteristic species of wet rocks and gravels in areas of Nardia compressa, Scapania uliginosa and Pohlia ludwigii. Alate snow-lie and associated meltwater burns high in Altitudinal range: 880–1340 m. the Scottish hills. It is most frequently found on dripping, north-facing crags along the ‘cornice line’ at the top of Andreaea nivalis is abundant in its core area on the Ben Nevis corries, where snow persists into the summer. Here the massif and in the Cairngorms but populations are much moss can form large cushions and on Ben Nevis it is smaller elsewhere in its range and it has not been possible remarkably abundant in this habitat with numerous to refind it at some of its old sites. There must be a concern associates, including Deschampsia cespitosa, Saxifraga that changes in snow accumulation and persistence as a stellaris, Anthelia julacea, Lophozia opacifolia, Marsupella result of climate change may affect the more marginal sites sphacelata, M. stableri, Andreaea alpina, A. rupestris, for this species. Ditrichum zonatum, Kiaeria falcata, K. starkei, Polytrichastrum sexangulare, Racomitrium lanuginosum and, rarely, Dioicous; capsules are occasional. Oedipodium griffithianum. In the Cairngorms it often occurs with Andreaea frigida in burns but it also occurs on open Andreaea nivalis is a large and easily identifiable moss and gravel areas which are very wet during snow melt and here is not likely to be confused with other species. The mapped it may form a complex mosaic with Marsupella sphacelata, distribution is therefore believed to be accurate. -

THE ANDEAN SPECIES of PILEA by Ellsworth P. Killip INTRODUCTION

THE ANDEAN SPECIES OF PILEA By Ellsworth P. Killip INTRODUCTION Pilea is by far the largest genus of Urticaceae. Weddell in his final monograph 1 of the family recognized 159 species as valid, about 50 of which were said to occur in the Andes of South America. That these species had a very limited range of distribution was indicated by the fact that more than 30 were known from only a single collection and that only 9 of the others were in any sense widely distributed in the Andean countries. Two, P. microphyUa and P. pubescens, occurred throughout the American Tropics, and P. kyalina and P. dendrophUa extended eastward in South America. In the 50 years following the publication of this monograph only 10 species were described from the Andean region. Because of the large number of specimens of Pilea collected by expeditions to the Andes sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, the New York Botanical Garden, the Gray Herbarium and the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, which were submitted to me for identification but which could not be assigned to any known species, I began the preparation of a mono- graph of all the Andean species. This was completed in 1935 but unfortunately could not be printed in its entirety at that time. Instead, a greatly abridged paper was published,2 which contained a key to all the Andean species, descriptions of 30 new ones, and a few changes of name and of rank. In this there was no opportunity to present descriptions of the earlier species or to discuss their synonymy. -

Mid-Holocene Social Interaction in Melanesia: New Evidence from Hammer-Dressed Obsidian Stemmed Tools

Mid-Holocene Social Interaction in Melanesia: New Evidence from Hammer-Dressed Obsidian Stemmed Tools ROBIN TORRENCE, PAMELA SWADLING, NINA KONONENKO, WALLACE AMBROSE, PIP RATH, AND MICHAEL D. GLASCOCK introduction Proposals that large-scale interaction and ceremonial exchange in the Pacific region began during the time of Lapita pottery (c. 3300–2000 b.p.) (e.g., Friedman 1981; Hayden 1983; Kirch 1997; Spriggs 1997) are seriously challenged by the extensive areal distribution of a class of retouched obsidian artifacts dated to the early and middle Holocene (c. 10,000–3300 b.p.) and known as ‘‘stemmed tools’’ (Araho et al. 2002). Find spots of obsidian stemmed tools stretch from mainland New Guinea to Bougainville Island and include the Trobriand Islands, various islands in Manus province, New Britain and New Ireland (Araho et al. 2002; Golson 2005; Specht 2005; Swadling and Hide 2005) (Fig. 1). Although other forms of tanged and waisted stone tool are known in Melanesia (e.g., Bulmer 2005; Fredericksen 1994, 2000; Golson 1972, 2001), the two types defined by Araho et al. (2002) as ‘‘stemmed tools’’ comprise distinctive classes because they usually have deep notches that delineate very well-defined and pronounced tangs. Type 1 stemmed tools are made from prismatic blades and have large and clearly demarcated, oval-shaped tangs. In contrast, the Type 2 group is more vari- able.Itisdefinedprimarilybytheuseof Kombewa flakes (i.e., those removed fromthebulbarfaceofalargeflake)forthe blank form, as described in detail in Robin Torrence is Principal Research Scientist in Anthropology, Australian Museum, Sydney NSW, [email protected]; Pamela Swadling is a Visiting Research Fellow, Archaeol- ogy and Natural History, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Can- berra ACT, [email protected]; Nina Kononenko is an ARC post-doctoral fellow in the School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry, University of Sydney, kononenko.nina@hotmail. -

Chapter 12 Productivity

Glime, J. M. 2017. Productivity. Chapt. 12. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. Ebook 12-1-1 sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 18 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 12 PRODUCTIVITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Productivity .......................................................................................................................................................... 12-2 Ecological Factors ................................................................................................................................................ 12-2 Ability to Invade ........................................................................................................................................... 12-2 Niche Differences ......................................................................................................................................... 12-3 Growth ................................................................................................................................................................. 12-3 Growth Measurements .................................................................................................................................. 12-4 Annual Length Increase ................................................................................................................................ 12-8 Uncoupling ...................................................................................................................................................