Just Post It: a Critical Discourse Analysis on Nike's Instagram

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nike's Pricing and Marketing Strategies for Penetrating The

Master Degree programme in Innovation and Marketing Final Thesis Nike’s pricing and marketing strategies for penetrating the running sector Supervisor Ch. Prof. Ellero Andrea Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Camatti Nicola Graduand Sonia Vianello Matriculation NumBer 840208 Academic Year 2017 / 2018 SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: THE NIKE BRAND & THE RUNNING SECTOR ................................................................ 6 1.1 Story of the brand..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Foundation and development ................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.2 Endorsers and Sponsorships ...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 Sectors in which Nike currently operates .................................................................................................. 8 1.2 The running market ........................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Competitors .................................................................................................................................... 12 1.4. Strategic and marketing practices in the market ............................................................................ 21 1.5 Nike’s strengths & weaknesses ...................................................................................................... -

NIKE Inc. STRATEGIC AUDIT & CORPORATE

NIKE Inc. STRATEGIC AUDIT & CORPORATE A Paper Presented as a Final Requirement in STRAMA-18 -Strategic Management Prepared by: IGAMA, ERICA Q. LAPURGA, BIANCA CAMILLE M. PIMENTEL, YVAN YOULAZ A. Presented to: PROF. MARIO BRILLANTE WESLEY C. CABOTAGE, MBA Subject Professor TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I. Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………………...……1 II. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...………1 III. Company Overview ………………………………………………………………………….2 A. Company Name and Logo, Head Office, Website …………………………...……………2 B. Company Vision, Mission and Values……………………………………………….…….2 C. Objectives …………………………………………………………………………………4 D. Organizational Structure …………………………………………………….…………….4 E. Corporate Governance ……………………………………………………………….……6 1. Board of Directors …………………………………………………………….………6 2. CEO ………………………………………………………………….………….……6 3. Ownership and Control ………………………………………………….……………6 F. Corporate Resources ………………………………………………………………...……9 1. Marketing ……………………………………………………………………….….…9 2. Finance ………………………………………………………………………………10 3. Research and Development ………………………………………………….………11 4. Operations and Logistics ……………………………………………………….……13 5. Human Resources ……………………………………………………...……………14 6. Information Technology ……………………………………………………….……14 IV. Industry Analysis and Competition ...……………………………...………………………15 A. Market Share Analysis ………………………………………………………...…………15 B. Competitors’ Analysis ………………………………………………………...…………16 V. Company Situation.………… ………………………………………………………….……19 A. Financial Performance ………………………………………………………………...…19 B. Comparative Analysis……………………… -

Nike's “Just Do It” Advertising Campaign

Mini-case Study: Nike’s “Just Do It” Advertising Campaign According to Nike company lore, one of the most famous and easily recognized slogans in advertising history was coined at a 1988 meeting of Nike’s ad agency Wieden and Kennedy and a group of Nike employees. Dan Weiden, speaking admiringly of Nike’s can-do attitude, reportedly said, “You Nike guys, you just do it.” The rest, as they say, is (advertising) history. After stumbling badly against archrival Reebok in the 1980s, Nike rose about as high and fast in the ‘90s as any company can. It took on a new religion of brand consciousness and broke advertising sound barriers with its indelible Swoosh, “Just Do It” slogan and deified sports figures. Nike managed the deftest of marketing tricks: to be both anti-establishment and mass market, to the tune of $9.2 billion dollars in sales in 1997. —Jolie Soloman “When Nike Goes Cold” Newsweek, March 30, 1998 The Nike brand has become so strong as to place it in the rarified air of recession-proof consumer branded giants, in the company of Coca- Cola, Gillette and Proctor & Gamble. Brand management is one of Nike’s many strengths. Consumers are willing to pay more for brands that they judge to be superior in quality, style and reliability. A strong brand allows its owner to expand market share, command higher prices and generate more revenue than its competitors. With its “Just Do It” campaign and strong product, Nike was able to increase its share of the domestic sport-shoe business from 18 percent to 43 percent, from $877 million in worldwide sales to $9.2 billion in the ten years between 1988 and 1998. -

Competing in Cedar: Nike, Superstar Athletes, and the Unseen Strangers Who Make Our Shoes

Competing in Cedar | 7 Competing in Cedar: Nike, Superstar Athletes, and the Unseen Strangers Who Make our Shoes Matthew S. Vos, Covenant College Abstract Nike’s global dominance in the athletic shoe and sports apparel market is without serious rival. Its current worth stands at $32.4 billion worldwide. Nike manufactures through an “export-processing system,” where the intellectual work of design and marketing takes place in the US and the labor-intensive assembly work takes place in hundreds of factories spread throughout Asia. Consequently, most Nike labor comes from young Asian women who typically work 10-13 hours per day with frequent forced overtime, and who earn around 50% of the wage required to meet subsistence needs. Nike’s cultural hegemony and “hip” image gains traction through celebrated athletes of color who enchant the public and powerfully showcase the company’s products. Using ideas from W. E. B. Du Bois, as well as Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems theory, this essay draws attention to the relationship between the women of color who work in Nike’s factories and big sport – in particular the athletes who profit greatly from Nike endorsements. The focus falls on how some exceptional athletes of color offer, perhaps unwittingly, a potent legitimation for a glitzy industry that is inextricable from the exploited labor and lives of girls and women of color – the unseen strangers who make our shoes. Keywords: Nike, strangers, sport, capitalist world-system, meta-national corporations, supply chains, export-processing, endorsements “Woe to him who builds his house by unrighteousness, and his upper rooms by injustice; who makes his neighbors work for nothing, and does not give them their wages; who says, “I will build myself a spacious house with large upper rooms,” and who cuts out windows for it, paneling it with cedar, and painting it with vermilion. -

The Role of Marketing Communication in Recognition of the Global Brand: a Case Study of Nike

The Role of Marketing Communication In Recognition of The Global Brand: A Case Study of Nike Thesis By Aleksander Madej Submitted in Partial fulfillment Of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science In Business Administration State University of New York Empire State College 2019 Reader: Tanweer Ali Statutory Declaration / Čestné prohlášení I, Aleksander Madej, declare that the paper entitled: The Role of Marketing Communication In Recognition of The Global Brand: A Case Study of Nike was written by myself independently, using the sources and information listed in the list of references. I am aware that my work will be published in accordance with § 47b of Act No. 111/1998 Coll., On Higher Education Institutions, as amended, and in accordance with the valid publication guidelines for university graduate theses. Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. Jsem vědom/a, že moje práce bude zveřejněna v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb., o vysokých školách ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a v souladu s platnou Směrnicí o zveřejňování vysokoškolských závěrečných prací. In Prague, 26.04.2019 Aleksander Madej 1 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my family for their support and the possibility to study at the Empire State College and the University of New York in Prague. Without them, I would not be able to achieve what I have today. Furthermore, I would like to express my immense gratitude to my mentor Professor Tanweer Ali, who helped and guided me along the way. I am incredibly lucky to have him. -

Advertising Practices: the Case of Nike, Inc

International Journal of Business and Management Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 8028, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 801X www.ijbmi.org || Volume 6 Issue 5 || May. 2017 || PP—45-47 Advertising Practices: The Case of Nike, Inc. Nur Hamizah Ahmad Zawawi1, Wan Rasyidah Abd Razak2 Master Student, Faculty of Business Management and Information Technology, Universiti Sultan Azlan Shah, Bukit Chandan, 33000 Kuala Kangsar, Perak Darul Ridzuan, Malaysia. Abstract: Nike, Inc. is a well-known company that produce branded sport shoes and quality sportswear that has been admired by everybody for their brand. Brand management of Nike, Inc. has play an important role to the company as they are successful in capturing brand minded of consumers in all levels. Although at first Nike, Inc. faced tremendous critics from public about their inconsistent attitude which constantly changing their plans as they wanted, suddenly they realized that they need to come out with something to encounter the perception of public by introducing ―Just Do It‖ campaign which give the spirit of doing something without hesitate. At the time being, Reebok, the biggest competitor of Nike, Inc. trying to compete with them in term of sales but Nike, Inc. has proved that their ―Just Do It‖ campaign has been successfully implemented. The ―Just Do It‖ campaign has become one of the advertising methods by the Nike, Inc. in order to promote their brands until now. Keywords: Advertising, Brand Promotion, ―Just Do It‖, Marketing, Nike, Inc., I. INTRODUCTION In this era of competitive market, businesses are struggling compete each other in order to be on the top of the world. -

Kickstart Catalog Ideas

Kickstart Catalog Ideas Brand: Nike 1: What symbols and signs can be combined to generate a new meaning, representing the product or serviceʼs advantage? The Nike swoosh can be used as a checkmark on a checklist to convey the idea of accomplishment (like accomplishing tasks on a list), and communicate the “Just Do It” concept. 2: What opportunities for ambiguity, double meanings or wordplay are there in the words you use to describe the benefit? The Nike Shox line of shoes could be used to replace the shock paddles used during defibrillation, using the double meaning/wordplay to associate the shoes with reviving life. 3: Can you construct rhymes, puns or other kinds of wordplay from the product or brand, which will underline the subject? For the NIKEiD line of customizable shoes, a list of “Iʼd (or iʼD) like to _______” statements could be depicted, followed by “What is your iʼD? Customize your footwear to fit your fitness goals with NIKEiD.” 4: How can the benefit be depicted by inverting something familiar into its opposite? Using pictures of either acts of laziness, competing brands, or just general bad ideas, invert the tagline to “Just donʼt do it” to contrast it with the positive outcomes of using the brand. 5: How will the product change the userʼs future? Using a split-screen execution, a commercial could show how an internʼs future is different with and without a pair of Nike shoes that he keeps handy to run a crucial errand. (The future with the Nike shoes shows the intern getting a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, while in the other future he is fired.) The tagline might say “Just in the Nike of time” for an extra wordplay effect. -

NIKE, Inc. Consolidated Statements of Income

PART II NIKE, Inc. Consolidated Statements of Income Year Ended May 31, (In millions, except per share data) 2015 2014 2013 Income from continuing operations: Revenues $ 30,601 $ 27,799 $ 25,313 Cost of sales 16,534 15,353 14,279 Gross profit 14,067 12,446 11,034 Demand creation expense 3,213 3,031 2,745 Operating overhead expense 6,679 5,735 5,051 Total selling and administrative expense 9,892 8,766 7,796 Interest expense (income), net (Notes 6, 7 and 8) 28 33 (3) Other (income) expense, net (Note 17) (58) 103 (15) Income before income taxes 4,205 3,544 3,256 Income tax expense (Note 9) 932 851 805 NET INCOME FROM CONTINUING OPERATIONS 3,273 2,693 2,451 NET INCOME FROM DISCONTINUED OPERATIONS — — 21 NET INCOME $ 3,273 $ 2,693 $ 2,472 Earnings per common share from continuing operations: Basic (Notes 1 and 12) $ 3.80 $ 3.05 $ 2.74 Diluted (Notes 1 and 12) $ 3.70 $ 2.97 $ 2.68 Earnings per common share from discontinued operations: Basic (Notes 1 and 12) $ — $ — $ 0.02 Diluted (Notes 1 and 12) $ — $ — $ 0.02 Dividends declared per common share $ 1.08 $ 0.93 $ 0.81 The accompanying Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements are an integral part of this statement. FORM 10-K NIKE, INC. 2015 Annual Report and Notice of Annual Meeting 107 PART II NIKE, Inc. Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income Year Ended May 31, (In millions) 2015 2014 2013 Net income $ 3,273 $ 2,693 $ 2,472 Other comprehensive income (loss), net of tax: Change in net foreign currency translation adjustment(1) (20) (32) 38 Change in net gains (losses) on cash flow hedges(2) 1,188 (161) 12 Change in net gains (losses) on other(3) (7) 4 (8) Change in release of cumulative translation loss related to Umbro(4) ——83 Total other comprehensive income (loss), net of tax 1,161 (189) 125 TOTAL COMPREHENSIVE INCOME $ 4,434 $ 2,504 $ 2,597 (1) Net of tax benefit (expense) of $0 million, $0 million and $(13) million, respectively. -

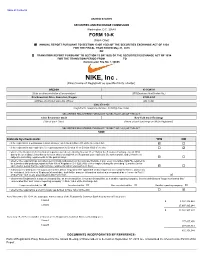

NIKE, Inc . (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED May 31, 2015 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO . Commission File No. 1-10635 NIKE, Inc . (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) OREGON 93-0584541 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation) (IRS Employer Identification No.) One Bowerman Drive, Beaverton, Oregon 97005-6453 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (503) 671-6453 (Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(B) OF THE ACT: Class B Common Stock New York Stock Exchange (Title of Each Class) (Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(G) OF THE ACT: NONE Indicate by check mark: YES NO • if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. • if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. • whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Creative Brief Nike Air Force 1S

Creative Brief Nike Air Force 1s Connor Carpani and Monique Ware Executive Summary: Nike is a household name in the world of sporting goods. Their products include athletic shoes, fashion shoes, apparel, and sports equipment (“Nike, Inc.,” 2014). Nike has a far reach, having stores in many countries worldwide. Their top competitors are Adidas, New Balance and Puma (“Hoovers,” 2014). While the Nike Air Force 1 has endured considerable commercial success, showing how Nike evolved as a brand proved to be important. Each prominent athletic shoe company has launched a popular sneaker model (“Hoovers,” 2014). The difference between these companies and Nike is that Nike outperformed its competitors with regards to marketing. In researching Air Force 1 and Nike as a whole, it became evident that Nike had been the pioneer in many different advertising segments. The data keenly expressed how Nike initiated trends in the past using athletes to advance their brand and how they intend to stay ahead of competitors in the future through modern environmental practices (“Nike, Inc.,” 2014). Table of Contents Title Page...……………………………………………………………… Page 1 Executive Summary ……………………………………………………… Page 2 Table of Contents……………………………………………………… Page 3 Background Information ………………………………………………… Page 4 Target Audience. ………………………………………………….…...… Page 5 Product Features and Benefits…………………………………………… Page 6 Current Brand Image …………………………………………………… Page 8 Desired Brand Image ………………………………………………………Page 9 Direct Competitors ……………………………………………………… Page 10 Indirect Competitors -

30 YEARS of JUST DO IT, ARE THEY CRAZY ENOUGH? En Kvalitativ Semiotisk Och Retorisk Analys Av Nikes Just Do It- Kampanj Dream Crazy

JMG – INSTITUTIONEN FÖR JOURNALISTIK, MEDIER OCH KOMMUNIKATION 30 YEARS OF JUST DO IT, ARE THEY CRAZY ENOUGH? En kvalitativ semiotisk och retorisk analys av Nikes Just Do It- kampanj Dream Crazy Nathalie Gerke, Andreas Moberg & Ida Tilemo Uppsats/Examensarbete: 15 hp Medie- och kommunikationsvetarprogrammet med inriktning Program och/eller kurs: PR, opinionsbildning och omvärld Nivå: Grundnivå Termin/år: Vt 2019 Handledare: Monika Unander Kursansvarig: Malin Sveningsson Abstract Uppsats/Examensarbete: 15 hp Medie- och kommunikationsvetarprogrammet med inriktning Program och/eller kurs: PR, opinionsbildning och omvärld Nivå: Grundnivå Termin/år: Vt 2019 Handledare: Monika Unander Kursansvarig: Malin Sveningsson Sidantal: 64 Antal ord: 19 893 Nyckelord: Varumärke, Politisering, Retorik, Semiotik, Nike Syfte: Vår studie ämnar att analysera hur Nike skapar mening i sin kommunikation och hur den relaterar till den moderna samhällskontexten. Genom analysen förväntar vi därmed oss kunna urskilja vilka värderingar och budskap som varumärket Nike laddas med. Teori: Semiotik, Retorik Metod: Kvalitativ innehållsanalys Material: Åtta affischer och en kampanjfilm från Nikes kommunikationskampanj Dream Crazy Resultat: Studiens resultat visar på att Nikes kampanj Dream Crazy gör att deras varumärke politiserar då det tillskrivs värden som är politiskt laddade. Detta beror till viss del på att den lanserades två månader innan mellanårsvalet men även på att det är Colin Kaepernick som är ansiktet utåt för kampanjen. Kaepernick är starkt förknippad med protestaktionen mot polisvåldet gentemot mörkhyade i USA vilket är en politiskt laddad fråga. Detta leder till att Nikes varumärke laddas med värden som tillskriver Nike en roll som förespråkare för just jämlikhet och rättvisa. Dessa värden kan anses vara etiskt korrekta och appellerar till konsumenter som vill associeras med sådana värderingar. -

The People Who Work for Nike Are Here for a Reason. I Hope It Is Because We Have a Passion for Sports, for Helping People Reach Their Potential

The people who work for Nike are here for a reason. I hope it is because we have a passion for sports, for helping people reach their potential. That’s why I am here. We strive to create the best athletic products in the world. We are all over the globe. Much has been said and written about our operations around the world. Some is accurate, some is not. In this report, Nike for the first time has assembled a comprehensive public review of our corporate responsibility practices. You will see a few accomplishments, and more than a few challenges. I offer it as an opportunity for you to learn more about our company. The last page indicates where you can give us feedback on how we can improve. Nike is a young company. A little more than a generation ago, a few of us skinny runners decided to build shoes. Our mission was to create a company that focused on the athlete and the product. We grew this company by investing our money in design, development, marketing and sales, and asking other companies to manufacture our products. That was our model in 1964, and it is our model today. We have been a global company from the start. That doesn’t mean we have always acted like a global company. We made mistakes, more than most, on our way to becoming the world’s biggest sports and fitness company. We missed some opportunities, deliberated when we should have acted, and vice versa. What we had in our favor was a passion for, and focus on, sports and athletes.