The Black Book of Georgetown Seeks to Inspire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithfield Review, Volume 20, 2016

In this issue — On 2 January 1869, Olin and Preston Institute officially became Preston and Olin Institute when Judge Robert M. Hudson of the 14th Circuit Court issued a charter Includes Ten Year Index for the school, designating the new name and giving it “collegiate powers.” — page 1 The On June 12, 1919, the VPI Board of Visitors unanimously elected Julian A. Burruss to succeed Joseph D. Eggleston as president of the Blacksburg, Virginia Smithfield Review institution. As Burruss began his tenure, veterans were returning from World War I, and America had begun to move toward a post-war world. Federal programs Studies in the history of the region west of the Blue Ridge for veterans gained wide support. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women Volume 20, 2016 suffrage, gained ratification. — page 27 A Note from the Editors ........................................................................v According to Virginia Tech historian Duncan Lyle Kinnear, “he [Conrad] seemed Olin and Preston Institute and Preston and Olin Institute: The Early to have entered upon his task with great enthusiasm. Possessed as he was with a flair Years of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Part II for writing and a ‘tongue for speaking,’ this ex-confederate secret agent brought Clara B. Cox ..................................................................................1 a new dimension of excitement to the school and to the town of Blacksburg.” — page 47 Change Amidst Tradition: The First Two Years of the Burruss Administration at VPI “The Indian Road as agreed to at Lancaster, June the 30th, 1744. The present Faith Skiles .......................................................................................27 Waggon Road from Cohongoronto above Sherrando River, through the Counties of Frederick and Augusta . -

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Enlumna THIRD ANNUAL VARSITY "G

25 VOL VIII GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C, MAY 12, 1927 ANNUAL OF 1927 THIRD ANNUAL VARSITY "G" BANQUET MAY 5th PROVES COMPLETE SUCESS (Enlumna DEDICATED TO HIM Capacity Crowd Attends Dinner at Willard Hotel—Coaches Rockne, of Notre Dame and Ingram, of Navy, Speak—John T. McGovern, By JOSEPH D. PORTER, '28 of Carnegie Foundation Gives Talk on "Value of Athletics"— Athletes Receive Certificates—Coach Louis Little Presented with Ye Domesday Booke is to be off the press and ready for distribution on May Token of Football Team's Esteem. 15th. Dedicated this year to Dr. George Tully Vaughan, who for thirty years has The long-anticipated Third Annual Varsity "G" Banquet took place as scheduled been connected with the Medical School, on the evening of Thursday, May 5th. In view of the purpose and universal appeal and incorporating as it does some novel of the affair, its success was expected, but it is scarcely to be imagined that even the ideas both as to format and treatment, fondest expectations of the committee were not surpassed. The capacity attend- the Bookc will take high place among all ance that filled all the tables in the huge banquet hall of the Willard Hotel, the the tomes of Domesday whose excellence spirit manifested, the splendid addresses of the distinguished speakers, and the at- has become traditional at Georgetown. tendance of members of athletic teams which were in their glory in the first years * * * of this century at Georgetown, all bore witness to this fact. The Rhode Island Georgetown Club ■ This affair was preceded by an in- sets an example in Alumni loyalty by formal re-uunion in the ante-room of the donating funds such as to give George- T0ND0RF ATTENDS hall. -

November 8, 2019 the Honorable Alex Azar Secretary Department of Health and Human Services Washington, DC Dear Secretary Azar: W

November 8, 2019 The Honorable Alex Azar Secretary Department of Health and Human Services Washington, DC Dear Secretary Azar: We write to you as parents, grandparents and educators to support the President's call to "clear the markets" of all flavored e-cigarettes. Safeguarding the health of our nation's children is paramount to us. Children must be protected from becoming addicted to nicotine and the dangers posed by tobacco product. We ask for your leadership in ensuring that all flavored e-cigarettes, including mint and menthol, are removed from the marketplace. The dramatic increase in the number of youth vaping is staggering and we see it in our communities every day. Every high school in the nation is dealing with this epidemic. From 2017 to 2019, there was a 135 percent increase, and now one out of every four high school youth (27.5%) in America use these products. More than 6 out of 10 of these teens use fruit, menthol or mint- flavored e-cigarettes. The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine concluded there is "substantial evidence" that if a youth or young adult uses an e-cigarette, they are at increased risk of using traditional cigarettes. Flavors in tobacco products attract kids. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the candy and fruit flavors found in e-cigarettes are one of the primary reason’s kids use them. A 2015 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that 81 percent of youth who have ever used tobacco products initiated with a flavored product. -

Xerox University Microfilms 900 North Zwb Road Ann Aibor, Michigan 40106 76 - 18,001

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produoad from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological meant to photograph and reproduce this document have bean used, the quality it heavily dependant upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing paga(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause e blurted image. You will find a good Image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. Whan a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of e large Sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with e small overlap. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could bo made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Institutes

Summer Programs for High School Students 2015 Welcome Packet The Institutes June 14-June 21 June 21-June 28 June 28-July 5 July 5-July 12 July 12-July 19 July 19-July 26 July 26-August 2 Table of Contents Welcome to Summer at Georgetown 3 Your Pre-Arrival Checklist 4 Institute Program Calendar 5 Preparing for Your Summer at Georgetown 6 Enroll in NetID Password Station 6 Register for Your Institute(s) 6 Apply for Your GOCard 7 Submit Your Campus Life Forms 7 Learning the Georgetown Systems 8 During Your Program 10 Residential Living 13 On Campus Resources 15 Check-In Day 16 Campus Map 18 Check-Out 19 Georgetown University Summer Programs for High School Students 3307 M St. NW, Suite 202 Washington, D.C. 20057 Phone: 202-687-7087 Email: [email protected] 2 WELCOME TO SUMMER AT GEORGETOWN! CONGRATULATIONS! Congratulations on your acceptance to the Institute program at Georgetown University’s Summer Pro- grams for High School Students! We hope you are looking forward to joining us on the Hilltop soon. Please make sure you take advantage of the resources offered by Georgetown University! The Summer and Special Programs office, a part of the School of Continuing Studies at Georgetown Universi- ty, provides world renowned summer programs that attract students from around the United States of America and the world. As you prepare for your arrival on Georgetown’s campus, our staff is available to provide you with academic advising and to help you plan and prepare for your college experience at Georgetown. -

FINAL REPORT of Special Committee on Marvin Center Name

Report of the Special Committee on the Marvin Center Name March 30, 2021 I. INTRODUCTION Renaming Framework The George Washington University Board of Trustees approved, in June of 2020, a “Renaming Framework,” designed to govern and direct the process of evaluating proposals for the renaming of buildings and memorials on campus.1 The Renaming Framework was drafted by a Board of Trustees- appointed Naming Task Force, chaired by Trustee Mark Chichester, B.B.A. ’90, J.D. ’93. The Task Force arrived at its Renaming Framework after extensive engagement with the GW community.2 Under the Renaming Framework, the university President is to acknowledge and review requests or petitions related to the renaming of buildings or spaces on campus. If the President finds a request for renaming “to be reasonably compelling when the guiding principles are applied to the particular facts,” the President is to: (1) “consult with the appropriate constituencies, such as the Faculty Senate Executive Committee, leadership of the Student Association, and the Executive Committee of the GW Alumni Association, on the merits of the request for consideration”; and (2) “appoint a special committee to research and evaluate the merits of the request for reconsideration.”3 Appointment of the Special Committee President LeBlanc established the Special Committee on the Marvin Center Name in July of 2020, and appointed Roger A. Fairfax, Jr., Patricia Roberts Harris Research Professor at the Law School as Chair. The Special Committee consists of ten members, representing students, staff, faculty, and alumni of the university, and two advisers, both of whom greatly assisted the Special Committee in its work.4 The Special Committee’s Charge Under the Renaming Framework, the charge of the Special Committee is quite narrow. -

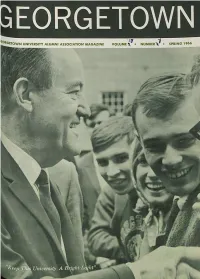

SPRING 1966 GEORGETOWN Is Published in the Fall, Winter, and Spring by the Georgetown University Alumni Association, 3604 0 Street, Northwest, Washington, D

SPRING 1966 GEORGETOWN is published in the Fall, Winter, and Spring by the Georgetown University Alumni Association, 3604 0 Street, Northwest, Washington, D. C. 20007 Officers of the Georgetown University Alumni Association President Eugene L. Stewart, '48, '51 Vice-Presidents CoUege, David G. Burton, '56 Graduate School, Dr. Hartley W. Howard, '40 School of Medicine, Dr. Charles Keegan, '47 School of Law, Robert A. Marmet, '51 School of Dentistry, Dr. Anthony Tylenda, '55 School of Nursing, Miss Mary Virginia Ruth, '53 School of Foreign Service, Harry J. Smith, Jr., '51 School of Business Administration, Richard P. Houlihan, '54 Institute of Languages and Linguistics, Mrs. Diana Hopkins Baxter, '54 Recording Secretary Miss Rosalia Louise Dumm, '48 Treasurer Louis B. Fine, '25 The Faculty Representative to the Alumni Association Reverend Anthony J . Zeits, S.J., '43 The Vice-President of the University for Alumni Affairs and Executive Secretary of the Association Bernard A. Carter, '49 Acting Editor contents Dr. Riley Hughes Designer Robert L. Kocher, Sr. Photography Bob Young " Keep This University A Bright Light' ' Page 1 A Year of Tradition, Tribute, Transition Page 6 GEORGETOWN Georgetown's Medical School: A Center For Service Page 18 The cover for this issue shows the Honorable Hubert H. Humphrey, Vice On Our Campus Page 23 President of the United States, being Letter to the Alumni Page 26 greeted by students in the Yard before 1966 Official Alumni historic Old North preceding his ad Association Ballot Page 27 dress at the Founder's Day Luncheon. Book Review Page 28 Our Alumni Correspondents Page 29 "Keep This University A Bright Light" The hard facts of future needs provided a con the great documents of our history," Vice President text of urgency and promise for the pleasant recol Humphrey told the over six hundred guests at the lection of past achievements during the Founder's Founder's Day Luncheon in New South Cafeteria. -

Hannah Wasco | Graduate School of Education and Human Development

Addressing Universities’ Historic Ties to Slavery Hannah Wasco | Graduate School of Education and Human Development Universities’ Historic Ties to Slavery Responding to History Social Justice Approach • Over the past 20 years, there has been a growing movement of Apologies: Should include an acknowledgment of the offense, acceptance of responsibility, expression of A social justice approach– encompassing both distributive and procedural universities in the United States acknowledging and addressing their regret, and a commitment to non-repetition of the offense. While some scholars say the single act of an justice– provides a framework for universities to both authentically historic ties to slavery. apology is enough, others argue that it is necessary to consider an apology as a process with no end point. address their historic ties to slavery and effectively correct present • Historical records irrefutably demonstrate that early American higher ------------------------------------------------- systems of racism and oppression on campus. education institutions permitted, protracted, and profited from the Reparations: Most often understood as money, reparations can also come in the form of land, education, ------------------------------------------------- African slave trade. mental health services, employment opportunities, and the creation of monuments and museums. Distributive Justice: American universities benefited directly and o Slaves constructed buildings, cleaned students’ rooms, and prepared However, discussions of reparations must be aware of the risk of “commodifying” suffering and falling into indirectly from the enslavement of human beings; social justice not only meals; slave labor on adjoining plantations funded endowments and the “one-time payment trap.” calls for the recognition of this historic inequity, but also demands that scholarships; and slaves were sold for profit and to repay debts. -

Georgetown University Frequently Asked Questions

GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY ADDRESS Georgetown University 37th and O Streets, NW Washington, DC 20057 DIRECTIONS TO GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY From Reagan National Airport (20 minutes) This airport is the closest airport to Georgetown University. A taxicab ride from Reagan National costs approximately $15-$20 one way. Take the George Washington Parkway North. Follow signs for Key Bridge/Route 50. Follow until Key Bridge exit. You will want to be in the left lane as you cross over Key Bridge. At the end of Key Bridge take a left at the light. This is Canal Road. Enter campus at the Hoya Saxa sign, to the right. This road will take you to main campus parking. See attached campus map for further directions. From Washington/Dulles Airport (40 minutes) Taxicabs from Dulles International cost approximately $50-$55 one way. Follow Dulles airport Access road to I-66. Follow I-66 to the Key Bridge Exit. Exit and stay in left lane. At the third light take a left and stay in one of the middle lanes. You will want to be in the left lane as you cross over Key Bridge. At the end of Key Bridge take a left at the light. This is Canal Road. Enter campus at the Hoya Saxa sign, to the right. This road will take you to main campus parking. See attached campus map for further directions. From New York to Washington D.C. By car, approximately 230 miles (4.5 hours) www.mapquest.com By train (approx 3 hours) approx. $120 each way www.amtrak.com By plane (approx 1.5 hours) approx $280 www.travelocity.com ACCOMMODATION The following hotels are closest to the University, for other hotel and discounted rates, you may like to try: www.cheaptickets.com www.cheaphotels.com Note: You can often get better rates through the above site than going through the hotel directly. -

The New York Times Published an Article Tracing the Life of One of the Slaves, Cornelius Hawkins, and His Modern-Day Descendants

http://nyti.ms/2c3j7Y5 U.S. By RACHEL L. SWARNS SEPT. 1, 2016 WASHINGTON — Nearly two centuries after Georgetown University profited from the sale of 272 slaves, it will embark on a series of steps to atone for the past, including awarding preferential status in the admissions process to descendants of the enslaved, university officials said Thursday. Georgetown’s president, John J. DeGioia, who announced the measures in a speech on Thursday afternoon, said he would offer a formal apology, create an institute for the study of slavery and erect a public memorial to the slaves whose labor benefited the institution, including those who were sold in 1838 to help keep the university afloat. In addition, two campus buildings will be renamed — one for an enslaved African- American man and the other for an African-American educator who belonged to a Catholic religious order. So far, Dr. DeGioia’s plan does not include a provision for offering scholarships to descendants, a possibility that was raised by a university committee whose recommendations were released on Thursday morning. The committee, however, stopped short of calling on the university to provide such financial assistance, as well as admissions preference. Dr. DeGioia’s decision to offer an advantage in admissions to descendants, similar to that offered to the children and grandchildren of alumni, is unprecedented, historians say. The preference will be offered to the descendants of all the slaves whose labor benefited Georgetown, not just the men, women and children sold in 1838. 1 of 4 More than a dozen universities — including Brown, Harvard and the University of Virginia — have publicly recognized their ties to slavery and the slave trade. -

Directors' Ruling Ends Student Boycott Threat Koeltl, Naylor First ~ Members of Board in Debate Tourney Change Status of .A.T Brandeis Univ

Vol. XLI}C," No.6 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C. Thursday, October 27, 1966 Directors' Ruling Ends Student Boycott Threat Koeltl, Naylor First ~ Members Of Board In Debate Tourney Change Status Of .A.t Brandeis Univ. GU-CU Scrimmage by Gene Pnyne Philodemic debaters John Koeltl "The Board of Directors of the and Mike Naylor compiled a 12-0 University, at its regular sched record to win first place at the uled meeting this afternoon, passed Brandeis University Invitational a motion to the effect that the Debate Tournament held last scrimmage planned for Oct. 29 weekend. Their undefeated record may be scheduled as a regular in the eight preliminary rounds game." qualified them in first seeded posi With this announcement, Cath tion for the four elimination olic University was added to the rounds. The final round against G~orgetown football schedule. A Northwestern resulted in a 3-2 proposed boycott of classes, a decision for Georgetown. "prank" letter and a last minute There were 36 teams entered in meeting of student leaders with the tournament, and Georgetown Father Campbell preceded the Oct. faced many of the top schools 22 decision. there. Koeltl and Naylor defeated There was more behind the .Stonehill College in the semi scheduling of this game than the finals. Brandeis in the quarters brief note from the Board of Di and Miami in the oetos. In pre rectors one week before the actual liminary competition, they scored playing date. Game status for for wins over Dartmouth, Marquette, mal 'scrimmage was the result of Western Reserve, Georgia, Ford a long series of incidents begin- ham, Norwich, Rutgers and Bran- A repeat of the 1963 student demonstration was averted this week when the Board of Directors responded ning at the end of the past aca deis.