Reading to Write/Writing to Read: Using Literature to Generate Writing in the Elementary Classroom Grades K-6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

(ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to Present

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to present 2014 Medal Winner: Locomotive, written and illustrated by Brian Floca (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) 2014 Honor Books: Journey, written and illustrated by Aaron Becker (Candlewick Press) Flora and the Flamingo, written and illustrated by Molly Idle (Chronicle Books) Mr. Wuffles! written and illustrated by David Wiesner (Clarion Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing) 2013 Medal Winner: This Is Not My Hat, written and illustrated by Jon Klassen (Candlewick Press) 2013 Honor Books: Creepy Carrots!, illustrated by Peter Brown, written by Aaron Reynolds (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division) Extra Yarn, illustrated by Jon Klassen, written by Mac Barnett (Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) Green, illustrated and written by Laura Vaccaro Seeger (Neal Porter Books, an imprint of Roaring Brook Press) One Cool Friend, illustrated by David Small, written by Toni Buzzeo (Dial Books for Young Readers, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group) Sleep Like a Tiger, illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski, written by Mary Logue (Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company) 2012 Medal Winner: A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka (Schwartz & Wade Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.) 2013 Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco (Disney · Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group) Grandpa Green by Lane Smith (Roaring Brook Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership) Me...Jane by Patrick McDonnell (Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.) 2011 Medal Winner: A Sick Day for Amos McGee, illustrated by Erin E. -

TRUTH and FALSEHOOD in SCIENCE and the ARTS the Arts

The authors discuss truth and falsehood in science and ARTS THE AND SCIENCE IN FALSEHOOD AND TRUTH the arts. They view truth as an irreducible point of refer- TRUTH AND FALSEHOOD ence, both in striving for elementary knowledge about the world and in seeking methods and artistic means IN SCIENCE of achieving this goal. The multilevel and multiple-aspect research presented here, conducted on material from different periods and different cultures, shows very clearly AND THE ARTS that truth and falsehood lie at the foundation of all human motivation, choices, decisions, and behaviors. At the Edited by same time, however, it reveals that every bid to extra- polate the results of detailed studies into generalizations Barbara Bokus, Ewa Kosowska aimed at universalization – by the very fact of their discursivation – either subjects the discussion to the rules of formal logic or situates it outside the realm of truth and falsehood. The Editors www.wuw.pl TRUTH AND FALSEHOOD IN SCIENCE AND THE ARTS TRUTH AND FALSEHOOD IN SCIENCE AND THE ARTS Edited by Barbara Bokus, Ewa Kosowska Reviewers Stefan Bednarek Stanisław Rabiej Commissioning Editor Ewa Wyszyńska Proofreading Joanna Dutkiewicz Index Łukasz Śledziecki Cover Design Anna Gogolewska Illustration on the Cover kantver/123RF Layout and Typesetting Marcin Szcześniak Published with financial support from the University of Warsaw Published with financial support from the Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, University of Warsaw © Copyright by Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2020 Barbara Bokus ORCID 0000-0002-3048-0055 Ewa Kosowska ORCID 0000-0003-4994-1517 ISBN 978-83-235-4220-9 (pdf online) ISBN 978-83-235-4228-5 (e-pub) ISBN 978-83-235-4236-0 (mobi) Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego 00-497 Warszawa, ul. -

Different Drummers

Special Issue: Different Drummers March/April 2013 Volume LXXXIX Number 2 ® Features Barbara Bader 21 Z Is for Elastic: The Amazing Stretch of Paul Zelinsky A look at the versatile artist’s career. Roger Sutton 30 Jack (and Jill) Be Nimble: An Interview with Mary Cash and Jason Low Independent publishers stay flexible and look to the future. Eugene Yelchin 41 The Price of Truth Reading books in a police state. Elizabeth Burns 47 Reading: It’s More Than Meets the Eye Making books accessible to print-disabled children. Columns Editorial Roger Sutton 7 See, It’s Not Just Me In which we celebrate the nonconforming among us. The Writer’s Page Polly Horvath and Jack Gantos 11 Two Writers Look at Weird Are they weird? What is weird, anyway? And will Jack ever reply to Polly? Different Drums What’s the strangest children’s book you’ve ever enjoyed? Elizabeth Bird 18 Seven Little Ones Instead Luann Toth 20 Word Girl Deborah Stevenson 29 Horrible and Beautiful Kristin Cashore 39 Embracing the Strange Susan Marston 46 New and Strange, Once Elizabeth Law 58 How Can a Fire Be Naughty? Christine Taylor-Butler 71 Something Wicked Mitali Perkins 72 Border Crossing Vaunda Micheaux Nelson 79 Wiggiling Sight Reading Leonard S. Marcus 54 Wit’s End: The Art of Tomi Ungerer A “willfully perverse and subversive individualist.” (continued on next page) March/April 2013 ® Columns (continued) Field Notes Elizabeth Bluemle 59 When Pigs Fly: The Improbable Dream of Bookselling in a Digital Age How one indie children’s bookstore stays SWIM HIGH ACROSS T H E SKY afloat. -

Updated Editions of Virginia Lee Burton's

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Fall 2009 Books for Children Use our 2 140 156 handy Harcourt Children’s Books Bill Peet: An Autobiography Holidays color-coded High-quality, award-winning key to determine books for more than eighty 141 158 each book’s years. Mariner Books Authors and Illustrators format. Check out the new adult titles by State, with Websites 19 from our highly acclaimed Clarion Books trade paperback line. 160 Picture Book As an adjective the word Awards & Accolades clarion means “brilliantly clear.” 142 An appropriate name Larousse Reference 161 for this distinctive imprint. The acclaimed line of bilingual Costumes and Website Board Book and foreign language dictionar - Resources 38 ies and books for children, for HMH Books more than 150 years. 162 Early Reader Fresh new formats and Index media tie-ins. 143 The American Heritage ® 167 Fiction 68 High School Dictionary Bookstore Representatives Houghton Mifflin The most comprehensive high Books for Children school dictionary available 168 A distinguished, award- today. Ordering Information Nonfiction winning publishing tradition. 144 101 Spring 2009 Backlist Paperback Sandpiper Paperbacks Imaginations soar with 153 our popular and classic Books by Publication Month Reference paperbacks. 154 Black History Month Cover 123 illustration Graphia Paperbacks © 2009 by Quality paperbacks for Jill McElmurry from today’s teen readers. Little Blue Truck Leads the Way by Alice Schertle Catalog design by Kat Black Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 222 Berkeley Street Boston, Massachusetts 02116 (617) -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

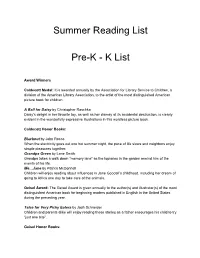

Summer Reading List Prek K List

Summer Reading List PreK K List Award Winners Caldecott Medal: It is awarded annually by the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association, to the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children. A Ball for Daisy by Christopher Raschka Daisy’s delight in her favorite toy, as well as her dismay at its accidental destruction, is clearly evident in the wonderfully expressive illustrations in this wordless picture book. Caldecott Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco When the electricity goes out one hot summer night, the pace of life slows and neighbors enjoy simple pleasures together. Grandpa Green by Lane Smith Grandpa takes a walk down “memory lane” as the topiaries in the garden remind him of the events of his life. Me…Jane by Patrick McDonnell Children will enjoy reading about influences in Jane Goodall’s childhood, including her dream of going to Africa one day to take care of the animals. Geisel Award: The Geisel Award is given annually to the author(s) and illustrator(s) of the most distinguished American book for beginning readers published in English in the United States during the preceding year. Tales for Very Picky Eaters by Josh Schneider Children and parents alike will enjoy reading these stories as a father encourages his child to try “just one bite”. Geisel Honor Books: I Broke My Trunk! by Mo Willems Beloved characters, Elephant and Piggie, are at it again in this unlikely story of how poor Gerald broke his trunk. See Me Run by Paul Meisel A dog has a funfilled day at the dog park in this easytoread story. -

Charlotte Zolotow ~R

A PROFILE OF CHARLOTTE ZOLOTOW ~R. b k iveri an ----:;.-- - ~~ --~~ ~ of books for .rorzng -readers Navigating the Neighborhood THE TEACHER'S ART : Dreaming of Kansas .,' Tales of ' Changelings -- INTERVIEW: Kevin Henkes Imagination ... and Risk By Emily Arnold McCully PLUS ~ New Books for Fall FALL 2001 ______ ,,,, .. ...,. 1 3 > 0 74470 94662 5 :$5.95 US $7.95 CAN It's Storytime! AUAN AHLliERG & RAYMOND BRIGGS The Adventures of 6arky Mavi~ BR OCK COLE THE ADVENTURES OF BERT Allan Ahlberg Illustrated by Raymond Briggs * "Top-drawer, absurd entertainment from two English masters of the droll ... This is brilliant stuff: simple tales that unleash great ponderings, li ke Bert's role in the universe. He could-believe it-be a savior of a sort. Bring us more Bert, please." -Starred, Kirkus Reviews $16.00 I 0-374-30092-5 / Ages 3-U EARTHQUAKE SOME FROM THE MOON Milly Lee SOME FROM THE SUN Illustrated b y Yangsook Choi Poems and Songs for E veryone "A good way to introduce the youngest Margot Zemach of readers to a calamitous event ... * "Wam1, lively, funny watercolors The illustrations' sculptured forms and ill ustrate nursery rhymes .. It will be geometric shapes make a pattern of well appreciated at the bedside, on the stability against dark vistas of smoke, lap, or at storytime. As a tribute to an fire, and destruction . .. enabling young artist or simply a book for sharing, readers to take in the scene and still it's a top-notch selection." find reassurance and comfort." -Starred, School Library Journal -Kirkus Reviews $17.00 I 0-374-39960-3 / All ages $16.00 I 0-374-39964-6 / Ages 4-8 Frances Foster Books LARKYMAVIS Brock Cole SHRINKING VIOLET * "Cole (Buttons) delivers a lyrical Cari Best and ever-relevant picture book .. -

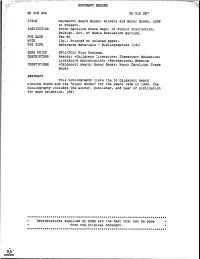

Document Resume Ed 318 004 Cs 212 287 Title

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 318 004 CS 212 287 TITLE Caldecott Award Books: Winners and Honor Books, 1938 to Present. INSTITUTION North Carolina State Dept. of Public Instruction, Raleigh. Div. of Media Evaluation Service. PUB DATE Feb 90 NOTE 13p.; Printed on colored paper. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Awards; *Childrens :dterature; Elementary Education; Literature Appreciation; *Recreational Reading IDENTIFIERS *Caldecott Award; Honor Books; North Carolina; Trade Books ABSTRACT This bibliography lists the 53 Caldecott Award winning books and the "Honor Books" for the years 1938 to 1990. The bibliography includes the author, publisher, and year of publication for each selection. (RS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ****************k***************************************************** 110 Media Evaluation Services Raleigh, North Carolina Division of Media and Technology February 1990 N.C. Department of Public instruction CALDECOTT AWARD BOOKS CD WINNERS AND HONOR BOOKS, 1938 TO PRESENT 1938 Award: ANIMALS OF THE BIBLE: A PICTURE BOOK. Illustrated by Dorothy P. rmwi Lathrop. Text selected by Helen Dean Fish. Lippincott, 1.937. Honor Books: SEVEN SIMEONS: A RUSSIAN TALE. Retold and illustrated by Boris g74. Artzybasheff. Viking, 1937. FOUR AND TWENTY BLACKBIRDS. Illustrated by Robert Lawson. 1 Compiled by Helen Dean Fish. Lippincott, 1937. 1939 Award: MEI LI. Written and illustrated by Thomas Handforth. Doubleday, 1938 Honor Books: THE FOREST POOL. Written and illustrated by Laura Adams Armer. Longmans, 1938. WEE GILLIS. Illustrated by Robert Lawson. Written by Munroe Leaf. Viking, 1938. SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS. Translated and illustrated by Wanda Gag. -

Changes a Child's First Poetry Collection

An Educator’s Guide to Changes A Child’s First Poetry Collection Written by Charlotte Zolotow and Illustrated by Tiphanie Beeke Note: The activities in this guide align with Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts for Grades K, 1, and 2, but standards for other grades may also apply. Prepared by We Love Children’s Books About the Book As the seasons change, there is new beauty waiting to be discovered. Twenty-eight of Charlotte Zolotow’s classic poems have been beautifully illustrated by Tiphanie Beeke to create a poetry collection for children of all ages. Accessible, insightful poems follow the rhythms and cycles of the changing year, bringing the seasons to life. About the Author Charlotte Zolotow – author, editor, publisher, and educator—had one of the most distinguished careers in the field of children’s literature. She was the author of more than 90 published books for children and was editor-publisher at HarperCollins where she worked with many of the great children’s and young adult authors of the time, including Laura Ingalls Wilder, Maurice Sendak, Paul Zindel, Francesca Lia Block, and Arnold Lobel. Born in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1915, she was married to Maurice Zolotow, a show-business biographer, and had two children. She died at age 98, in 2013, in the home she had lived in for more than 55 years. Changes: A Child’s First Poetry Collection is published on the occasion of Charlotte Zolotow’s 100th birthday. About the Illustrator Tiphanie Beeke attended the Royal College of Art in London, where she earned a master’s degree in communication and design and has since specialized in children’s books, though her work can also be seen on greeting cards, gift wrap, and textiles. -

March Is Reading Month

March Is Reading Month: Choosing Rigorous, Inspiring Books For Michigan’s K-12 Students “My top priority as Governor is to make sure Michigan's children have the world opened up to them by learning how to read. A rock-solid education with a firm foundation of reading skills will give our children access to every opportunity in life to succeed. Every month in Michigan should be Reading Month, not just March." —Governor Jennifer Granholm In Michigan we are reminded that ALL students need to engage in reading opportunities that will enhance thinking; meet high, rigorous English language arts standards; and provide an intellectual challenge commensurate with learning goals aimed at the 21st Century. Reading Month is an opportune time to reflect on the quality of literature we are using to inspire students. Readers become leaders. Reading is the one skill that everyone needs to learn, and stay fresh and dynamic. To succeed in life we need to understand what we read. The best way to improve understanding is to read a lot. Below, educators will find noteworthy, recommended, and award-winning booklists that can be used in our quest for providing the best. By considering skill levels and developmental range, as well as the needs and interests of students, educators can select books that appeal to the broad spectrum. The Internet is a convenient source of online information. By checking out the online sources you will find well-organized children's sections arranged by grade level, age range, interests, and themes. Print materials such as Book Talk in Instructor and magazines such as BookLinks are excellent resources that can provide current information about excellent book selections, as well as, the Internet-based resources below. -

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Ebook Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback: 488 pages Publisher: Schocken Books Inc.; Reprint edition (November 14, 1995) Language: English ISBN-10: 0805210555 ISBN-13: 978-0805210552 Product Dimensions:5.2 x 1 x 8 inches ISBN10 0805210555 ISBN13 978-0805210 Download here >> Description: The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka’s stories, from the classic tales such as “The Metamorphosis,” “In the Penal Colony,” and “A Hunger Artist” to shorter pieces and fragments that Max Brod, Kafka’s literary executor, released after Kafka’s death. With the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka’s narrative work is included in this volume. Hello All,I recently purchased this book in faith, though I was also frustrated by the lack of information in the book description. So, I will provide here for you the table of contents so that whoever purchases this book from now on can know exactly what they are getting:(By the way, the book is beautifully new & well designed, with the edges of the pages torn, not cut.)When it says the complete stories, it means it. The foreword assures that the book contains all of the fiction that Kafka committed to publication during his lifetime. That meas his novels, which he did NOT intend to be published but left note in his will to be destroyed, are NOT included: The Trial, America, The Castle.