Antoni Folkers Modern Architecture in Africa Critical Reflections On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Geography 243 Geography of Africa

Geography 243 Geography of Africa: Local Resources and Livelihoods in a Global Context 1 First Year Seminar Fall Semester, 2018 Class Time and Location : 1:20-2:50, Tuesdays & Thursdays, Rm 105, Carnegie Hall Instructor : Bill Moseley Office : Rm 104d, Carnegie Hall Office Hours : 1:30-2:30pm MW, 3-4pm on Thurs, or by appointment Phone : 651-696-6126. Email : [email protected] Writing Assistant: Rosie Chittick ([email protected] ). Office hrs: 6:30-8pm MW, Dupre, Geography Dept Office Lounge, Carnegie 104 Course Description and Objectives From the positive images in the film Black Panther , to the derogatory remarks of President Trump, the African continent often figures prominently in our collective imagination. This class goes beyond the superficial media interpretations of the world’s second largest region to complicate and ground our understanding of this fascinating continent. Africa South of the Sahara has long been depicted in the media as a place of crisis – a region of the world often known for civil strife, disease, corruption, hunger and environmental destruction. This perception is not entirely unfounded, after all, Ebola in west and central Africa, the kidnapping of school girls in northern Nigeria, or civil war and hunger in Somalia are known problems. Yet Africa is a place of extraordinarily diverse, vibrant, and dynamic cultures. Many Africans also expertly manage their natural resources, are brilliant agriculturalists and have traditions of democratic governance at the local level. As such, the African story is extremely diverse and varied. The thoughtful student must work hard to go beyond the superficial media interpretations of the vast African continent and appreciate its many realities without succumbing to a romanticized view. -

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Thesis Final Copy V11

“VIENS A LA MAISON" MOROCCAN HOSPITALITY, A CONTEMPORARY VIEW by Anita Schwartz A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts & Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in Teaching Art Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2011 "VIENS A LA MAlSO " MOROCCAN HOSPITALITY, A CONTEMPORARY VIEW by Anita Schwartz This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Angela Dieosola, Department of Visual Arts and Art History, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty ofthc Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster ofArts in Teaching Art. SUPERVISORY COMMIITEE: • ~~ Angela Dicosola, M.F.A. Thesis Advisor 13nw..Le~ Bonnie Seeman, M.F.A. !lu.oa.twJ4..,;" ffi.wrv Susannah Louise Brown, Ph.D. Linda Johnson, M.F.A. Chair, Department of Visual Arts and Art History .-dJh; -ZLQ_~ Manjunath Pendakur, Ph.D. Dean, Dorothy F. Schmidt College ofArts & Letters 4"jz.v" 'ZP// Date Dean. Graduate Collcj;Ze ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Professor John McCoy, Dr. Susannah Louise Brown, Professor Bonnie Seeman, and a special thanks to my committee chair, Professor Angela Dicosola. Your tireless support and wise counsel was invaluable in the realization of this thesis documentation. Thank you for your guidance, inspiration, motivation, support, and friendship throughout this process. To Karen Feller, Dr. Stephen E. Thompson, Helena Levine and my colleagues at Donna Klein Jewish Academy High School for providing support, encouragement and for always inspiring me to be the best art teacher I could be. -

Resume of Chief Examiners' Report for the General

RESUME OF CHIEF EXAMINERS’ REPORT FOR THE GENERAL SUBJECTS SECTION 1. STANDARD OF PAPERS All the Chief Examiners reported that the standard of the papers compared favourably with that of previous years. 2. PERFORMANCE OF CANDIDATES The Chief Examiners expressed varied opinions about candidates’ performance. An improved performance was reported by the Chief Examiners of History, Economics, Geography 1B, Christian Religious Studies, Islamic Studies, Government and Social Studies. However the Chief Examiner for Geography 2 reported a slight decline in the performance of candidates. 3. A SUMMARY OF CANDIDATES’ STRENGTHS The Chief Examiners noted the following commendable features in the candidates’ scripts. (1) Orderly Presentation of material and good expression The subjects for which candidates were commended for orderly presentation of material and clarity of expression include Christian Religious Studies, Economics, History, Islamic Studies , Government and Social Studies . (2) Relevant examples and illustrations An appreciable number of candidates in Geography 1, Social Studies, History and Government were commended by the Chief Examiners for buttressing their points with relevant examples. (3) Compliance with the rubrics Candidates of History, Christian Religious Studies, Government , Geography 1 and 2 were reported to have adhered to the rubrics of the paper very strictly. (4) Legible Handwriting The Chief Examiners for Christian Religious Studies, Economics , History, Islamic Studies, Government and Social Studies commended candidates for good handwriting. 4. A SUMMARY OF CANDIDATES’WEAKNESSES The Chief examiners reported the following as weaknesses of most of the candidates: (1) Inability to draw diagrams properly The Chief Examiner for Geography 1B reported that the candidates failed to draw well-labelled diagrams and could not interpret graph and other statistical data. -

“Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: the Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-2, Issue-2, Mar-Apr- 2017 ISSN: 2456-7620 “Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: The Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C. Department of Theatre and Media Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Abstract— The private and the opposition-controlled environment where totalitarianism, dictatorship and other media have most often been taxed by Black African forms of unjust socio-political strictures reign. They are governments with being adepts of adversarial journalism. not to be intimidated or cowed by any aggressive force, to This accusation has been predicated on the observation kill stories of political actions which are inimical to public that the private media have, these last decades, tended to interest. They are rather expected to sensitize and educate dogmatically interpret their watchdog role as being an masses on sensitive socio-political issues thereby igniting enemy of government. Their adversarial inclination has the public and making it sufficiently equipped to make made them to “intuitively” suspect government and to solid developmental decisions. They are equally to play view government policies as schemes that are hardly – the role of an activist and strongly campaign for reforms nay never – designed in good faith. Based on empirical that will bring about positive socio-political revolutions in understandings, observations and secondary sources, this the society. Still as watchdogs and sentinels, the media paper argues that the same accusation may be made are expected to practice journalism in a mode that will against most Black African governments which have promote positive values and defend the interest of the overly converted the state-owned media to their public totality of social denominations co-existing in the country relation tools and as well as an arsenal to lambaste their in which they operate. -

About the Geography of Africa

CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 146 IV. Early and Medieval African Kingdoms Teaching Idea Create an overhead of Instructional What Teachers Need to Know Master 21, The African Continent, and A. Geography of Africa use it to orient students to the physical Background features discussed in this section. Have them use the distance scale to Africa is the second-largest continent. Its shores are the Mediterranean compute distances, for example, the Sea on the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Red Sea and Indian Ocean length and width of the Sahara. to the east, and the Indian Ocean to the south. The area south of the Sahara is Students might be interested to learn often called sub-Saharan Africa and is the focus of Section C, “Medieval that the entire continental United Kingdoms of the Sudan,” (see pp. 149–152). States could fit inside the Sahara. Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea The Red Sea separates Africa from the Arabian Peninsula. Except for the small piece of land north of the Red Sea, Africa does not touch any other land- Name Date mass. Beginning in 1859, a French company dug the Suez Canal through this nar- The African Continent row strip of Egypt between the Mediterranean and the Red Seas. The new route, Study the map. Use it to answer the questions below. completed in 1869, cut 4,000 miles off the trip from western Europe to India. Atlantic and Indian Oceans The Atlantic Ocean borders the African continent on the west. The first explorations by Europeans trying to find a sea route to Asia were along the Atlantic coast of Africa. -

Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914

Delineating Dominion: Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert H. Clemm Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor Alan Beyerchen Ousman Kobo Copyright by Robert H Clemm 2012 Abstract This dissertation documents the ways in which cartography was used during the Scramble for Africa to conceptualize, conquer and administer newly-won European colonies. By comparing the actions of two colonial powers, Germany and Britain, this study exposes how cartography was a constant in the colonial process. Using a three-tiered model of “gazes” (Discoverer, Despot, and Developer) maps are analyzed to show both the different purposes they were used for as well as the common appropriative power of the map. In doing so this study traces how cartography facilitated the colonial process of empire building from the beginnings of exploration to the administration of the colonies of German and British East Africa. During the period of exploration maps served to make the territory of Africa, previously unknown, legible to European audiences. Under the gaze of the Despot the map was used to legitimize the conquest of territory and add a permanence to the European colonies. Lastly, maps aided the capitalist development of the colonies as they were harnessed to make the land, and people, “useful.” Of special highlight is the ways in which maps were used in a similar manner by both private and state entities, suggesting a common understanding of the power of the map. -

The Architectural Representation of Islam Tural This Book Is a Study of Dutch Mosque Designs, Objects of Heated Public Debate

THE ARCHI THE R EPRESEN tat T EC THE ARCHITECTURAL REPRESentatION OF ISlam T ION OF OF ION This book is a study of Dutch mosque designs, objects of heated public UR debate. Until now, studies of diaspora mosque designs have largely A consisted of normative architectural critiques that reject the ubiquitous L ‘domes and minarets’ as hampering further Islamic-architectural evolution. I The Architectural Representation of Islam: Muslim-Commissioned Mosque SL Design in The Netherlands represents a clear break with the architectural A critical narrative, and meticulously analyzes twelve design processes M for Dutch mosques. It shows that patrons, by consciously selecting, steering and replacing their architects, have much more influence on their mosques than has been generally assumed. Through the careful transformation of specific building elements from Islamic architectural history to a new context, they literally aim to ‘construct’ the ultimate Islam. Their designs thus evolve not in opposition to Dutch society, but to those versions of Islam that they hold to be false. ERIC ROOSE THE ARCHITECTURAL Eric Roose (1967) graduated with M.A. degrees in Public International Law, Cultural Anthropology, and Architectural History (the latter cum laude) from REPRESENtatION OF ISLAM Leiden University. Between 2004 and 2008 he conducted PhD research at Leiden University, and between 2005 and 2008 was also an Affiliated PhD Fellow at the International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern MUSLIM-COMMISSIONED World (ISIM) in Leiden. He is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Amsterdam School for Social Science Research (ASSR) of the University of Amsterdam. MOSQUe DeSIGN ISBN 978 90 8964 133 5 ERIC ERIC IN THe NetHERLANDS R OOS E Eric Roose ISIM ISIM DISSERTATIONS ISIM EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/15/2020 10:54 AM via MAASTRICHT UNIVERSITY AN: 324550 ; Roose, Eric.; The Architectural Representation of Islam : Muslim-commissioned Mosque Design in the Netherlands Copyright 2009. -

A Design Research Journal of the Moorish Influence of Art and Design in Andalusia Written and Designed by Breanna Vick

FOLD UN - A design research journal of the Moorish influence of art and design in Andalusia written and designed by Breanna Vick. This project is developed as a narrative report describing personal interactions with design in southern Spain while integrating formal academic research and its analysis. Migration of Moorish Design and Its Cultural Influences in Andalusia Migration of Moorish Design and Its Cultural Influences in Andalusia UROP Project - Breanna Vick Cover and internal design by Breanna Vick. Internal photos by Breanna Vick or Creative Commons photo libraries. All rights reserved, No part of this book may be reproduced in any form except in case of citation or with permission in written form from author. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Author Bio Breanna Vick is a Graphic Designer based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She is interested in developing a deeper understanding of different methods of design research. On a site visit to Morocco and Spain in May through June of 2017, Breanna tested her knowledge of design research by observing Moorish design integrated in Andalusia. By developing a research paper, establishing sketchbooks, collecting photographs, and keeping journal entries, she was able to write, design and construct this narrative book. With Breanna’s skill-set in creating in-depth research, she has a deep understanding of the topics that she studies. With this knowledge, she is able to integrate new design aesthetics into her own work. Project Objective My undergraduate research project objective is to advance my understanding of how Moorish design appears in cities located throughout the southern territory of Spain. -

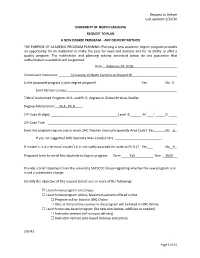

Request to Deliver Last Updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY of NORTH

Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA REQUEST TO PLAN A NEW DEGREE PROGRAM – ANY DELIVERY METHOD THE PURPOSE OF ACADEMIC PROGRAM PLANNING: Planning a new academic degree program provides an opportunity for an institution to make the case for need and demand and for its ability to offer a quality program. The notification and planning activity described below do not guarantee that authorization to establish will be granted. Date: February 24, 2018 Constituent Institution: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Is the proposed program a joint degree program? Yes No X Joint Partner campus Title of Authorized Program: M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Global Africana Studies Degree Abbreviation: M.A., Ph.D. CIP Code (6-digit): Level: B M I D CIP Code Title: Does the program require one or more UNC Teacher Licensure Specialty Area Code? Yes No _ X If yes, list suggested UNC Specialty Area Code(s) here __________________________ If master’s, is it a terminal master’s (i.e. not solely awarded en route to Ph.D.)? Yes ___ No__X_ Proposed term to enroll first students in degree program: Term Fall Year 2020 Provide a brief statement from the university SACSCOC liaison regarding whether the new program is or is not a substantive change. Identify the objective of this request (select one or more of the following) ☒ Launch new program on campus ☐ Launch new program online; Maximum percent offered online ___________ ☐ Program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ One or more online courses in the program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ Launch new site-based program (list new sites below; add lines as needed) ☐ Instructor present (off-campus delivery) ☐ Instructor remote (site-based distance education) Site #1 Page 1 of 31 Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 (address, city, county, state) (max. -

AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES 2013: the Lagos Dialogues “All Roads Lead to Lagos”

AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES 2013: The Lagos Dialogues “All Roads Lead to Lagos” ABOUT AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES A SERIES OF BIANNUAL EVENTS African Perspectives is a series of conferences on Urbanism and Architecture in Africa, initiated by the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Kumasi, Ghana), University of Pretoria (South Africa), Ecole Supérieure d’Architecture de Casablanca (Morocco), Ecole Africaine des Métiers de l’Architecture et de l’Urbanisme (Lomé, Togo), ARDHI University (Dar es Salaam, Tanzania), Delft University of Technology (Netherlands) and ArchiAfrika during African Perspectives Delft on 8 December 2007. The objectives of the African Perspectives conferences are: -To bring together major stakeholders to map out a common agenda for African Architecture and create a forum for its sustainable development -To provide the opportunity for African experts in Architecture to share locally developed knowledge and expertise with each other and the broader international community -To establish a network of African experts on sustainable building and built environments for future cooperation on research and development initiatives on the continent PAST CONFERENCES INCLUDE: Casablanca, Morocco: African Perspectives 2011 Pretoria/Tshwane, South Africa: African Perspectives 2009 – The African City CENTRE: (re)sourced Delft, The Netherlands: African Perspectives 2007 - Dialogues on Urbanism and Architecture Kumasi, Ghana June 2007 - African Architecture Today Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: June 2005 - Modern Architecture in East Africa around independence 4. CONFERENCE BRIEF The Lagos Dialogues 2013 will take place at the Golden Tulip Hotel Lagos, from 5th – 8th December 2013. We invite you to attend this ground breaking international conference and dialogue on buildings, culture, and the built environment in Africa. -

Factors Affecting Uptake of Male Circumcision Among Students

FACTORS AFFECTING UPTAKE OF MALE CIRCUMCISION AMONG STUDENTS. CASE STUDY: MAKERERE UNIVERSITY, KAMPALA BY MWEETE SHARON 16/U/745 216001401 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF STATISTICS OF MAKERERE UNIVERSITY. JULY 2019 i ii iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am most thankful to the Almighty God for enabling me to accomplish this work. Special thanks go to my University supervisor Mrs. Afazali Zabibu and all my lecturers at Makerere for all the knowledge they have imparted in me since 2016. I am indebted to most sincerely thank my parents Mr. Zijjampola Paul and Mrs. Zijjampola Robinah for their unwavering financial, moral support and affection they have always rendered to me. May God bless you all! iv DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my parents and family, for their love and support during the period of the study. v TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ........................................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. ACADEMIC SUPERVISOR’S APPROVAL ............................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ......................................................................................................... iv DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................v ACRONYMS ..............................................................................................................................x