The Jesuit Science Network 79 3.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Bibliographic Knowledgebase Syndeo Regional Metadata Services

Track 3 – Library Services G. Connecting Regions with Global Impact The National Bibliographic Knowledgebase Syndeo Regional Metadata Services Neil Grindley, Head of Resource Discovery, Jisc Axel Kaschte, Product Strategy Director, OCLC The National Bibliographic Knowledgebase NEIL GRINDLEY, HEAD OF RESOURCE DISCOVERY, JISC Does 4 things… Providing and developing a Supporting the provision and Our network of national and Our R&D work, paid for entirely network infrastructure and management of digitalcontent regional teams provide local by our major funders, identifies related services that meet the for UK education and research engagement, advice and emerging technologies and needs of the UK research and support to help you get the develops them around your education communities most out of our service offer particular needs Jisc Bibliographic Data Services Acquisition Discovery Delivery Collection Management Select Check Manage Specific Unknown Select Link to Document Interlibrary Management Title Collection Book Availability Metadata Title Title Best Copy Best Copy Delivery Loan of Stock Usage Benchmarking Bibliographic Management Jisc Zetoc Jisc Reading Collections Circulation Copac Historical Lists KB+ Archives Hub Data JUSP Jisc Texts Services E-books Pilot SUNCAT CORE Copac CCM Tools NBK NBK NBK NBK Advice, guidance, technical support, quality assessment and new service development https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/transforming-library-support-services Current Jisc Investments https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/national-bibliographic-knowledgebase -

Newsletter of the IFLA Document Delivery and Resource Sharing Section

Newsletter of the IFLA Document Delivery and Resource Sharing Section ISSN 1016-281X September 2005 Table of Contents A Note from the Chair 2 Minutes of the Mid-Winter SC Meeting: Prague, 24-25 February 2005 3 New members’ biographies 6 News from members: Carol Smale (Canada) 8 News from members: Assunta Arte (Italy) News from members: Margarita Moreno (Australia) Open Session: Oslo conference (including abstracts of papers) 10 SUBITO and German developments in copyright law. Uwe Rosemann (German National Library of science and Technology, Hannover, Germany) 11 Standing Committee Members 14 This Newsletter is also available on IFLA Net www.ifla.org 1 A Note from the Chair Dear Section members, The 71st World Library and Information Congress in Oslo is now behind us and just a few weeks from now hopefully many of you will be travelling to Tallinn to participate in the 9th IFLA Interlending and Document Supply International Conference. During the WLIC in Oslo the Section had a very successful programme on Perspectives on supply of electronic documents. The first of the three papers that were presented there you will find in this issue of our newsletter while the remaining two will be published in the following issue. In his paper on SUBITO and German developments in copyright law Dr. Uwe Rosemann puts focus on what is happening not only in Germany but in many other countries as well if publishers and associates succeed in having their own way. The German court will have to decide if – as claimed by the publishers – interlibrary loan activities not only happening between German and foreign libraries but between libraries within Germany as well are illegal. -

The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(S): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(s): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring, 2013), pp. 29-36 Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/19654 Prandium: The Journal of Historical Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, (2013) Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Nicholas Overgaard “Obedience should be blind and prompt,” Ignatius of Loyola reminded his Jesuit brothers a decade after their founding in 1540.1 By the turn of the seventeenth century, the incumbent Superior General Claudio Aquaviva had reiterated Loyola’s expectation of “blind obedience,” with specific regard to Jesuit support for the Catholic Church during the Galileo Affair.2 Interpreting the relationship between the Jesuits and Copernicans like Galileo Galilei through the frame of “blind obedience” reaffirms the conservative image of the Catholic Church – to which the Jesuits owed such obedience – as committed to its medieval traditions. In opposition to this perspective, I will argue that the Jesuits involved in the Galileo Affair3 represent the progressive ideas of the Church in the early seventeenth century. To prove this, I will argue that although the Jesuits rejected the epistemological claims of Copernicanism, they found it beneficial in its practical applications. The desire to solidify their status as the intellectual elites of the Church caused the Jesuits to reject Copernicanism in public. However, they promoted an intellectual environment in which Copernican studies – particularly those of Galileo – could develop with minimal opposition, theological or otherwise. -

Moniteljr BIBLIOGRAPHIQUE

SUPPLÉMENT AUX « ÉTUDES >> MONITElJR BIBLIOGRAPHIQUE DE LA COMPAGNIE DE JÉSUS catalogue des ouvrages publiés par les Peres de la Compagnie de Jésus et des publications d'auteurs étrangers relatives a la Compagnie. Recommandé par le T. R. P. Général FASCICULE XVIII -1898 PREMIER SEMESTRE : J ANVIER-JUIN PAR CARLOS SOMMERVOGEL, S. J. -~- RÉDACTION DES « ÉTUDES )) PARIS, RUE MONSIEUR, 15 SEPTEMBRE 1898 ~-n1¡ 1 '1 ¡ r¡: 1 1 1 1 : ,1 ¡1 li : 1 j'\ '; 1 1 ' ' : 1:1: 1 1 1 1 I 11 1 : 1 '.I 1 1 1 ¡ ,¡' [1 ! ' ¡ ' ~ :'1 1' 1l 1¡· .:1, ¡:1 1 j ' ~ t 11 1 '1 1 i l 1, 11:1 1 r , 11¡ 11• 1 11, 1 I¡ I ·: , I'' ' , 1 1.1 :1 ,:1¡ ! ¡ 1 111 l 11¡· ti! 11 , 1 1: 11 1 11'1 1 ' ,, ' ' 1 i.: ¡, 1 ' ; 1: : 1 1 1!l 1 i' ~ i ! : 11 :¡ 1 1 ~ 1 ,, 1 ,' ' 1 1 ! : ¡ i ! ' '1: ! ~ • ,I 1 MONIT.EUR BIBLIOGRAPIIIQUE DE LA COMPAGNJE DE JÉSUS 1898 J ANVIER-JUIN L'astérisque, accompagnant les numéros d'ordre, indique les publications décrites de visu. THÉOLOGIE Écrltu.re Sainte. Lempl (Thomas). - Zur Erklarung des Hexaemeron; - da ns: Theolog. pi·akt. Van Kasteren (Jan). - Scripturis Qitai·tnlschrift, p. 9-28, 28Hl2. [*7 tisch Overzicht ; - dans : Studien op godsdienstig ... gebied, t. L, p. 78-108. [*1 Hontheim (J oseph). - Bemerkungen zu Job 3; - dans: Zeitsc!wi{t fü1· Kath. Maas (Antoiue). - Le monvement Theologie, t. XXII, p. 172-9. - ... Zu Job des études bibliques ; daus : Reviie 4-5; - p. 404-13. [* 8 catho ligue des Revues, 3• année, 1898, p. -

Lessons from Reading Clavius

Christopher Clavius, S.J. Calendar Reform Lessons from Clavius Conclusion Lessons from reading Clavius Anders O. F. Hendrickson Concordia College Moorhead, MN MathFest, Pittsburgh August 5, 2010 Christopher Clavius, S.J. Calendar Reform Lessons from Clavius Conclusion Outline 1 Christopher Clavius, S.J. 2 Calendar Reform 3 Lessons from Clavius 4 Conclusion Christopher Clavius, S.J. Calendar Reform Lessons from Clavius Conclusion Christopher Clavius, S.J. (1538–1612) Christopher Clavius, S.J. Calendar Reform Lessons from Clavius Conclusion Clavius’s life Born in Bamberg c. 1538 1555 received into the Society of Jesus by St. Ignatius Loyola 1556–1560 studied philosophy at Coimbra 1561–1566 studied theology at the Collegio Romano 1567–1612 professor of mathematics at Collegio Romano 1570 published Commentary on the Sphere of Sacrobosco 1574 published edition of Euclid’s Elements c. 1572–1582 on papal calendar commission c. 1595 retired from teaching, focused on research 1612 died in Rome Christopher Clavius, S.J. Calendar Reform Lessons from Clavius Conclusion Clavius as teacher As a teacher, Clavius Taught elementary (required) courses in astronomy Led a seminar for advanced students Fought for status of mathematics in the curriculum Christopher Clavius, S.J. Calendar Reform Lessons from Clavius Conclusion Calendar Reform: Solar How to keep the calendar in synch with solar year (365.24237 days, equinox to equinox): Julian calendar: 365.25 days Gregorian calendar: omit 3 leap days every 400 years; hence 365.2425 days Christopher Clavius, S.J. Calendar Reform Lessons from Clavius Conclusion Calendar Reform: Lunar Easter is the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after the vernal equinox. -

192 College & Research Libraries March 1997 Ness, the Implication

192 College & Research Libraries March 1997 ness, the implication being that these Finally, a book published in 1996 sectors are more service oriented than should surely give great emphasis to are libraries. Because this reviewer be- networked information and the digital lieves strongly that the service ethic has library, because one can reasonably ex- declined precipitously in all segments pect that users will exploit such re- of society (including libraries) over the sources in ways different from the ways past forty years (try to reach any hu- they exploit print resources and, thus, man being by telephone today; try to criteria relating to “service quality” get a reply to any business correspon- could be different. Although some dence), he finds this almost entirely rather oblique references occur in the platitudinous. A statement of commit- text, the topic is never really addressed ment to excellence does not, in itself, head-on and the terms digital library, elec- guarantee even adequacy. tronic information, Internet, or even net- Chapter 8 gives us a few pages on work do not appear in the index (which, what “leadership” means in libraries in any case, is rather pathetic). and chapter 9 tells us that service qual- This is not a book I can recommend ity is a critical issue in academic librar- to either library managers or students ies and in higher education in general. of library science. Both the theoretical None of this is new or inspiring. discussion and the survey instruments Chapter 7 presents a hodgepodge of have been done better before. A methods that libraries could use to ex- hardbound version (ISBN 1-56750-209-1) amine quality of service, everything is also available at an almost unbeliev- from reshelving surveys to OPAC trans- able price of $52.50 for fewer than 200 action logs; and chapter 6 (which seems pages.—F. -

Bringing Jesuit Bibliography Into the Twenty-First Century: Boston College’S New Sommervogel Online

journal of jesuit studies 3 (2016) 61-83 brill.com/jjs Bringing Jesuit Bibliography into the Twenty-First Century: Boston College’s New Sommervogel Online Kasper Volk Boston College [email protected] Chris Staysniak Boston College [email protected] Abstract This article introduces The Boston College Jesuit Bibliography: The New Sommervogel Online (nso), an ongoing project of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies at Boston College in conjunction with the publisher Brill. Named for the famed nineteenth- century Jesuit bibliographer Carlos Sommervogel, the nso is the modern incarnation of a long and distinctive tradition of Jesuit bibliography. It harnesses the capabilities of the digital age to create a comprehensive, searchable, and open-access database cata- loging thousands of Jesuit-themed books, book chapters, articles, and book reviews. By consolidating and organizing existing scholarship on the Society of Jesus, the new resource will provide a valuable service to scholars around the world and facilitate additional development within the already dynamic and rapidly expanding field of Jesuit studies. Keywords Pedro de Ribadeneyra – Philippe Algambe – Brothers De Backer – Auguste Carayon – Carlos Sommervogel – László Polgár – Jesuit bibliography – digital humanities – New Sommervogel Online © Volk and Staysniak, 2016 | doi: 10.1163/22141332-00301004 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 4.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 01:14:22PM via free access <UN> 62 Volk and Staysniak An exciting new project is in the works at Boston College, and it has the poten- tial to revolutionize the field of Jesuit studies. -

About the Cover: Christopher Clavius, Astronomer and Mathematician

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 46, Number 4, October 2009, Pages 669–670 S 0273-0979(09)01269-5 Article electronically published on July 7, 2009 ABOUT THE COVER: CHRISTOPHER CLAVIUS, ASTRONOMER AND MATHEMATICIAN GERALD L. ALEXANDERSON As early as 1232 John of Holy Wood, an English astronomer known usually by the Latin translation of his name, Sacro Bosco, observed that the Julian calendar was becoming increasingly inaccurate over time. It wasn’t until roughly 300 years later that Christopher Clavius, a German Jesuit, formulated the improved Gregorian calendar that was adopted by Pope Gregory XIII and instituted on Friday, October 15, 1582. This is the astronomical work for which Clavius is best known but he was a polymath who wrote on various branches of science and mathematics. Born in 1538, two years before St. Ignatius Loyola’s Society of Jesus was approved by the Catholic Church, Clavius became one of the earliest members of the Order that would have considerable influence on the history of astronomy and mathematics, particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries. The title page shown on the cover, with its armillary sphere, is from one of Clavius’s most important works, the In Sphæram Ioannis de Sacro Bosco Commentarius (Rome, 1570), which not only presented the much earlier work of the 13th century Sacro Bosco but included evidence of Clavius’s awareness of the Copernican theory as described in the De Revolutionibus Orbium Cœlestium of 1543 (though Clavius remained loyal to the theory of Ptolemy). It also provides evidence of Clavius’s long time correspondence with Galileo, in which at one point he provided confirmation of some of Galileo’s calculations on Venus and Saturn. -

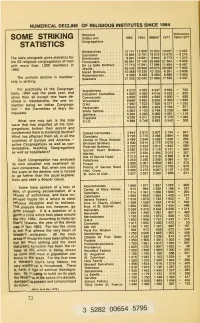

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Zeitschrift Für Die Geschichte Und Altertumskunde Ermlands, Band 44, 1988

Zeitschrift für die Geschichte und Altertumskunde Ermlands Band 44 1988 Zeitschrift für die Geschichte und Altertumskunde Ermlands Im Namen des Historischen Vereins für Ermland e. V. (Sitz Münster i. W.) herausgegeben vom Vorstand des Vereins Band44 1988 ------~~---- ZGAE = Zeitschrift für die Geschichte und Altertumskunde Ermlands Schriftleitung: Dr. Hans-Jürgen Karp Selbstverlag des Historischen Vereins für Ermland Ermlandweg 22, 4400 Münster i. W. Auslieferung für den Buchhandel durch den Verlag A. Fromm, Osnabrück 1988 ISSN 0342-3344 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Aufsätze Brigitte Poschmann Das Ermland in der deutschen Geschichtsschreibung der Ge- genwart .......................................................................................... 7 Warmia w niemieckiej wsp6lczesnej historiografii .. .. ... .. ..... 25 Warmia in Present German History ............................................. 26 Anneliese Triller Tomasz Ujejski (1612 -1689) - ein heiligmäßiger ermländischer Dompropst . .. ......... ... .. .. .... .... .. .. .... ... ............ ... .. ... .. ... .. .. ... 29 Tomasz Ujejsk.i (1612- 1689) - uwaZ8ny za swi~tego prepozyt warmiflski . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ........ 35 Tomasz Ujejski (1612-1689)- a Saintly Warmian Chapter Pro- vost ................................................................................................. 35 Janusz Jasinski Der Ermländische Verein von 1848 ... .. ..... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. ... ... ... .. 37 Stowarzyszenie Warminskie z 1848 roku -

Christopher Clavius Astronomer and Mathematician

IL NUOVO CIMENTO Vol. 36 C, N. 1 Suppl. 1 Gennaio-Febbraio 2013 DOI 10.1393/ncc/i2013-11496-3 Colloquia: 12th Italian-Korean Symposium 2011 Christopher Clavius astronomer and mathematician C. Sigismondi ICRA, International Center for Relativistic Astrophysics, and Sapienza Universit`adiRoma P.le Aldo Moro 5 00185, Roma, Italy Universit´e de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, Laboratoire H. Fizeau - Parc Valrose, 06108, Nice, France Istituto Ricerche Solari di Locarno - via Patocchi 57 6605 Locarno Monti, Switzerland GPA, Observat´orio Nacional - Rua General Cristino 77 20921-400, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil ricevuto il 9 Marzo 2012 Summary. — The Jesuit scientist Christopher Clavius (1538-1612) has been the most influential teacher of the renaissance. His contributions to algebra, geometry, astronomy and cartography are enormous. He paved the way, with his texts and his teaching for 40 years in the the Collegio Romano, to the development of these sciences and their fruitful spread all around the World, along the commercial paths of Portugal, which become also the missionary paths for the Jesuits. The books of Clavius were translated into Chinese, by one of his students Matteo Ricci “Li Madou” (1562–1610), and his influence for the development of science in China was crucial. The Jesuits become skilled astronomers, cartographers and mathematicians thanks to the example and the impulse given by Clavius. This success was possible also thanks to the contribution of Clavius in the definition of the ratio studiorum, the program of studies, in the Jesuit colleges, so influential for the whole history of modern Europe and all western World. PACS 01.65.+g – Philosophy of science. -

The Premonstratensian Project

Chapter 7 The Premonstratensian Project Carol Neel 1 Introduction The order of Prémontré, in the hundred years after the foundation of its first religious community in 1120, instantiated the vibrant religious enthusiasm of the long twelfth century. Like other religious orders originating in the medieval reformation of Catholic Christianity, the Premonstratensians looked to the early church for their inspiration, but to the rule of Augustine rather than to the rule of Benedict whose reinterpretation defined the still more numerous and influential Cistercians.1 The Premonstratensian framers, in the first in- stance their founder Norbert of Xanten (d. 1134), understood the Augustinian rule to have been composed by the ancient bishop for his own community of priests in Hippo, hence believed it the most ancient and venerable of constitu- tions for intentional religious life in the Latin-speaking West.2 As Regular Can- ons ordained to priesthood and living together in community under the rule of Augustine rather than monks according to a reformed Benedictine model, the Premonstratensians were then both primitivist and innovative. While the or- der of Prémontré embraced the novelty of its own project in interpreting the Augustinian ideal for a Europe reshaped by Gregorian Reform, burgeoning lay piety, and a Crusader spirit, at the same time it homed to an ancient paradigm of a priesthood informed and inspired by the sharing of poverty and prayer. Among numerous contemporaneous reform movements and religious com- munities claiming return to apostolic values, the medieval Premonstratensians thus maintained a vivid consciousness of the distinctiveness of their charism as a mixed apostolate bringing together contemplative retreat and active en- gagement in the secular world.