Usage of Nasta'liq in the Modern Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

Inpage Urdu Manual

http://www.axiscomputers.com [email protected] Concept SOFTWARE .. . . (version) . 1 Horizontal . CharacterScript Letters & VowelsLigature . . Windows 95, 3.11 Full stop 5.0 (Decorative Work) (Spot Color Separation) . . 2 . . 3 Spell Check Kerning ME NT 4 6 .......................................................................................... ......................................................................................... .................................................................................. ..................................................................................... .............................................................................................. ......................................................................................... ................................................................................................. ..................................................................................... ................................................................................ ................................................................................. .......................................................................................... .................................................................................................. .............................................................................................. ....................................................................................................... -

1: Scope and Important of Urdu: Urdu Is a Standardized Register of the Hindustani Language It Is the National Language and Ling

1: Scope And Important Of Urdu: Urdu Is A Standardized Register Of The Hindustani Language It Is The National Language And Lingua Franca Of Pakistan, And An Official Language Of Six States Of India. It Is Also One Of The 22 Official Languages Recognized In The Constitution Of India. Urdu Is Historically Associated With The Muslims Of The Northern Indian Subcontinent. Apart From Specialized Vocabulary, Urdu Is Mutually Intelligible With Standard Hindi, Another Recognized Register Of Hindustani. The Urdu Variant Received Recognition And Patronage Under British Rule When The British Replaced The Persian And Local Official Languages With The Urdu And English Languages In The North Indian Regions Of Jammu and Kashmir In 1846 And Punjab In 1849. Urdu, Like Hindi, Is A Form Of Hindustani. It Evolved From The Medieval (6th To 13th Century) Apabhraṃśa Register Of The Preceding Shauraseni Language, A Middle Indo-Aryan Language That Is Also The Ancestor Of Other Modern Languages, Including The Punjabi Dialects. Urdu Developed Under The Influence Of The Persian And Arabic Languages, Both Of Which Have Contributed A Significant Amount Of Vocabulary To Formal Speech around 99% Of Urdu Verbs Have Their Roots In Sanskrit And Prakrit. Although The Word Urdu Itself Is Derived From The Turkic Word Ordu Or Orda, From Which English Horde Is Also Derived, Turkic Borrowings In Urdu Are Minimal And Urdu Is Not Genetically Related To The Turkic Languages. Urdu Words Originating From Chagatai And Arabic Were Borrowed Through Persian And Hence Are Personalized Versions Of The Original Words. For Instance, The Arabic Ta' Marbuta Changes To He Or Te . -

International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding (IJMMU) Vol

Comparative Study of Post-Marriage Nationality Of Women in Legal Systems of Different Countries http://ijmmu.com [email protected] International Journal of Multicultural ISSN 2364-5369 Volume 2, Issue 6 and Multireligious Understanding December, 2015 Pages: 41-57 Public Perception on Calligraphic Woodcarving Ornamentations of Mosques; a Comparison between East Coast and Southwest of Peninsula Malaysia Ahmadreza Saberi1; Esmawee Hj Endut1; Sabarinah Sh Ahmad1; Shervin Motamedi2,3; Shahab Kariminia4; Roslan Hashim2,3 1 Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, 40450, Malaysia Email: [email protected] 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 3 Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences (IOES), University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 4 Department of Architecture, Faculty of Art, Architecture and Urban Planning, Najafabad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Najafabad, Isfahan, Iran Abstract Woodcarving ornamentation is considered as, a national heritage and can be found in many Malaysian mosques. Woodcarvings are mostly displayed in three different motifs, namely floral, geometry and calligraphy. The application of floral and geometry motifs is to convey an abstract meaning of Islamic teachings to the viewers. However, the calligraphic decorations directly express the messages of Allah almighty or the sayings of the prophets to the congregations. Muslims are the main users of mosques as these are places for prayers as well as other religious and community activities. Therefore, the assessment of users’ opinion about this type of decoration needs to be investigated. This paper aims to evaluate the perception of two groups of mosque users on the calligraphic woodcarving ornamentations from two regions, namely the East Coast and Southwest of Peninsula Malaysia. -

A COMPARATIVE STUDY of ENGLISH and KURDISH CONNECTIVES in NEWSPAPER OPINION ARTICLES Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ENGLISH AND KURDISH CONNECTIVES IN NEWSPAPER OPINION ARTICLES Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Rashwan Ramadan Salih BA, MA School of English University of Leicester 2014 A comparative study of English and Kurdish connectives in newspaper opinion articles Abstract This thesis is a comparative study that investigates English and Kurdish connectives which signal conjunctive relations in online newspaper opinion articles. This study utilises the Hallidayan framework of connectives in light of the principles of Relevance Theory established by Sperber and Wilson (1995). That is, connectives are considered in terms of their procedural meanings; i.e. the different interpretations they signal within different contexts, rather than their conceptual meanings. It finds that Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) classification of conjunctive relations and connectives needs to be modified, in order to lay out a clearer classification of English connectives that could account for their essential characteristics and properties. This modified classification would also help classify Kurdish connectives with greater accuracy. The comparison between connectives from both languages is examined through the use of translation techniques such as creating paradigms of correspondence between the equivalent connectives from both languages (Aijmer et al, 2006). Relevance Theoretic framework shows that any given text consists of two segments (S1 and S2), and these segments are constrained by different elements according to the four sub-categories of conjunctive relations. Different characteristics of connectives are considered in relation to the different subcategories of the Hallidayan framework of the conjunctive relations as follows: additive: the semantic content of the segments S1 and S2; adversative: the polysemy of the connectives; causal-conditional: iconicity in the order of the segments and temporal: the time scenes in the segments S1 and S2 The thesis comprises eight chapters. -

View / Download 7.3 Mb

Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Janice Hyeju Jeong 2019 Abstract While China’s recent Belt and the Road Initiative and its expansion across Eurasia is garnering public and scholarly attention, this dissertation recasts the space of Eurasia as one connected through historic Islamic networks between Mecca and China. Specifically, I show that eruptions of -

Applying Arabic Kashida to Latin Letters in Display Typography

Applying Arabic Kashida to Latin Letters in Display Typography Antoine Abi Aad Ph.D., Lecturer - Coordinator, Advertising and Graphic Design, Académie Libanaise des Beaux- Arts, UOB, Lebanon [email protected] Abstract-Arabic, like Hebrew, is a script that was Syriac scripts were developed from Aramaic. Figure extensively used visually because of religious 2 represents one sentence written in Syriac and in 5 purposes. In Islam, as in Judaism, the visual Arabic . The similarities between the two scripts are representation of saints, prophets and holy people is evident. not allowed. However, the desire and the passion to create images were stronger than the fear of blasphemy. Figure 1 has three word-pictures: the first is a Masoretic illustrated text written in Hebrew1 and the other two are animals drawn with Arabic letters: the bird is written in Turkish2 while the tiger is Figure 2. Syriac and Arabic letters written in Persian3. The Kashida replaces the letter space used with Latin letters. Furthermore, it improves the appearance of justified text by visually lengthening words rather than increasing the blank between the letters. Interestingly, the Kashida can be stretched unevenly in one word, serving aesthetics needs. Figure 1. Words as image Today, people using Arabic letters are linked to many centuries of visual words, a heritage that can be transformed into display typography. It is pointless to keep reminiscing on the splendors of great eras. Artists and designers should rather look inward yet forward and produce new visuals. This paper explores display typography through the kashida, the soul of Arabic writing. Applied to Latin letters, the Figure 3. -

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

![[2010] Manuscript Learnability Ver 2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6918/2010-manuscript-learnability-ver-2-166918.webp)

[2010] Manuscript Learnability Ver 2

PERSPECTIVES ON KANO Copyright 2010 ©A Jama'ar Inuwar Kano (Kano Foundation) Initiative for kanoonline.com First Published in Nigeria December, 2010 lSBN: 978-8092-53-5 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or. utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written the or permission of the author. Printed & Bound by Tellettes Consulting Coy Ltd • 2 PERSPECTIVES ON KANO Contents CHAPTER 1 The Kano Physical Environment 7 CHAPTER2 Assessment of Water Demand Pattern in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Case Study of the Greater Kano Area, Nigeria 47 CHAPTER3 Aspects of Kano Cultural Tourism 57 CHAPTER4 The Structure of Kano Economy 83 CHAPTERS Introduction, Spread and Development of Islam in Kano Since 1350 A.D. 111 CHAPTER6 Manuscript Learnability and Indig;enous Knowledge for Development-The Kano Hausa Ajami in Historical Context 139 CHAPTER? The Influence of North African Arabs on Kano City 200 CHAPTERS Multiculturalism in Kano State of Nigeri.a- Processes and Dynamics 239 CHAPTER9 A Participatory Account of the Jihad in Kano 268 CHAPTER 10 Sarki Goma: The Sakkwato Jihad and the Transformation of the Hausa Built Environment 290 CHAPTER 11 Community Mobilization in Traditional Societies: A Contextual Appraisal of the Role of Oramedia in tl1e 1804 Usman Dan Fodio Jihad Movement 311 CHAPTER 12 The Hajj Exercise in Kano: Challenges, Constraints and Drawbacks 339 CHAPTER 13 Biography of Select Kano Merchants, 1853-1955 373 CHAPTER 14 Language Patterns, Etiquette and Address Forms in Kano Emir's Palace. -

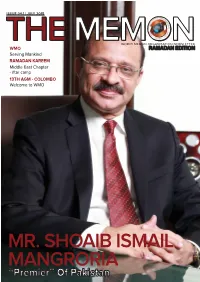

MR. SHOAIB ISMAIL MANGRORIA “Premier” of Pakistan the MEMON | ISSUE 04.1 INTRODUCTION

ISSUE 04.1 | JULY 2015 THETHE MEMONMEMONWORLD MEMON ORGANISATION NEWSLETTER WMO RAMADAN EDITION Serving Mankind RAMADAN KAREEM Middle East Chapter - iftar camp 13TH AGM - COLOMBO Welcome to WMO MR. SHOAIB ISMAIL MANGRORIA “Premier” Of Pakistan THE MEMON | ISSUE 04.1 INTRODUCTION THETHE MEMONMEMON INTRODUCTION World Memon Organisation - Serving Mankind I stood undaunted during the Gujarat I am getting together a group of young- riots and rehabilitated my aicted sters in the Big Apple to do community brothers and sisters. I walked in neck work. I organise events to promote deep waters to build homes for flood brotherhood and sports every month in victims in Sindh. I drove to shelters in Dubai. I ran the Mumbai marathon to Durban with medical supplies to treat fund a worthy cause. the injured in the Xenophobic attacks. I am the youth wing of WMO. I am a member of WMO. We are the future of Mankind. We uplift mankind I was knighted by the Queen of I build homes. I educate children. I England for my extensive charitable provide a brighter future and make this work. I was awarded the “Presidential world a better place. Order of Meritorious Service” by the President of the Republic of Botswana I donate to WMO. for my exceptional generosity and We uphold Mankind. philanthropy. I was honoured by the Premier of Pakistan for my dedication I sent blankets to shivering children in and passion towards community work. the winter of war torn Syria. I collected funds for relief packages to be delivered I am WMO. in flood ravaged Malawi.