Transcript – Deborah Harkness Interview 29/12/20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYON the Thames Landscape Strategy Review 3 3 7

REACH 11 SYON The Thames Landscape Strategy Review 3 3 7 Landscape Character Reach No. 11 SYON 4.11.1 Overview 1994-2012 • There has been encouraging progress in implementing Strategy aims with the two major estates that dominate this reach, Syon and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. • Syon has re-established its visual connection with the river. • Kew’s master-planning initiatives since 2002 (when it became a World Heritage Site) have recognised the key importance of the historic landscape framework and its vistas, and the need to address the fact that Kew currently ‘turns its back on the river’. • The long stretch of towpath along the Old Deer Park is of concern as a fl ood risk for walkers, with limited access points to safe routes. • Development along the Great West Road is impacting long views from within Syon Park. • Syon House and grounds: major development plan, including re- instatement of Capability Brown landscape: re-connection of house with river (1997), opening vista to Kew Gardens (1996), re-instatement of lakehead in pleasure grounds, restoration of C18th carriage drive, landscaping of car park • Re-instatement of historic elements of Old Deer Park, including the Kew Meridian, 1997 • Kew Vision, launched, 2008 • Kew World Heritage Site Management Plan and Kew Gardens Landscape Masterplan 2012 • Willow spiling and tree management along the Kew Ha-ha • Invertebrate spiling and habitat creation works Kew Ha-ha. • Volunteer riverbank management Syon, Kew LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 4.11.2 The Syon Reach is bordered by two of the most signifi cant designed landscapes in Britain. Royal patronage at Richmond and Kew inspired some of the initial infl uential works of Bridgeman, Kent and Chambers. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early M

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 © Copyright by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia by Sara Victoria Torres Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Christine Chism, Co-chair Professor Lowell Gallagher, Co-chair My dissertation, “Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia,” traces the legacy of dynastic internationalism in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and early-seventeenth centuries. I argue that the situated tactics of courtly literature use genealogical and geographical paradigms to redefine national sovereignty. Before the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, before the divorce trials of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon in the 1530s, a rich and complex network of dynastic, economic, and political alliances existed between medieval England and the Iberian kingdoms. The marriages of John of Gaunt’s two daughters to the Castilian and Portuguese kings created a legacy of Anglo-Iberian cultural exchange ii that is evident in the literature and manuscript culture of both England and Iberia. Because England, Castile, and Portugal all saw the rise of new dynastic lines at the end of the fourteenth century, the subsequent literature produced at their courts is preoccupied with issues of genealogy, just rule, and political consent. Dynastic foundation narratives compensate for the uncertainties of succession by evoking the longue durée of national histories—of Trojan diaspora narratives, of Roman rule, of apostolic foundation—and situating them within universalizing historical modes. -

The Geoarchaeology of Past River Thames Channels at Syon Park, Brentford

THE GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF PAST RIVER THAMES CHANNELS AT SYON PARK, BRENTFORD Jane Corcoran, Mary Nicholls and Robert Cowie SUMMARY lakes created during the mid-18th century (discussed later). The western lake extends Geoarchaeological investigations in a shallow valley in from the Isleworth end of the park to the Syon Park identified two superimposed former channels main car park for both Syon House and the of the River Thames. The first formed during the Mid Hilton London Syon Park Hotel (hereafter Devensian c.50,000 bp. The second was narrower and the hotel site), while the other lies to the formed within the course of the first channel at the end north-east near the Brentford end of the of the Late Devensian. Both would have cut off part of park. The south-west and north-east ends the former floodplain, creating an island (now occupied of the arc are respectively centred on NGR by Syon House and part of its adjacent gardens and 516650 176370 and 517730 177050 (Fig 1). park). The later channel silted up early in the Holocene. In dry conditions part of the palaeochannel The valley left by both channels would have influenced may be seen from the air as a dark cropmark human land use in the area. During the Mesolithic the on the south-east side of the west lake and is valley floor gradually became dryer, although the area visible, for example, on an aerial photograph continued to be boggy and prone to localised flooding till taken in August 1944. modern times, leaving the ‘island’ as a distinct area of This article presents a summary of the geo- higher, dryer land. -

Final Thesis

Courtly Mirrors: The Politics of Chapman’s Drama Shona McIntosh, M.A. (Hons), M.Phil. Submitted in fulfilment of the degree requirements for a Doctorate in Philosophy to the University of Glasgow Department of English Literature, Faculty of Arts November 2008 2 Contents Abstract .................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements.................................................................................. 5 Author’s declaration ................................................................................ 6 Abbreviations .......................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1................................................................................................ 8 ‘Spirit to Dare and Power to Doe’: George Chapman at the Jacobean Court ............................................................................................................... 8 Modern Literary Criticism and George Chapman’s Drama .................. 14 General Studies of Chapman’s Drama............................................. 14 Chapman’s Ethics and Philosophy .................................................. 19 Political Readings of Chapman’s Work............................................. 27 Court Masques and Court Politics ................................................... 35 Themes of Sexuality and Gender in Chapman Criticism .................. 36 Text and Canon: Authorship, Dating and Source Material ............... 38 Radical -

01395 513340

Canon Paul Cummins The Presbytery, Radway, Sidmouth, EX10 8TW 01395 513340 Church of The Most Precious Blood Retired Priest: Fr Patrick Kilgarriff Exeter Hospital Chaplain: Canon John Deeny 01392 272815 [email protected] www.churchofthemostpreciousblood SIXTH WEEK OF EASTER C PSALTER 2 sidmouth.co.uk @SidmthRCParish Saturday 5:30pm Vigil Mass Sunday 10:30am Sixth Sunday of Easter People of the Parish Monday 10:00am Memorial Mass of St Athanasius Tuesday 6:00pm Feast of St Philip and St James the Apostles Rita Bradley RIP Wednesday 10:00am Feast of the English Martyrs Agnes Evans RIP Thursday 9:00am Memorial Mass of St Richard Reynolds Jane Rodgers RIP Friday 10:00am Easter Weekday Mass Confessions After weekday Mass or by appointment Let us keep in our prayers those who are sick and housebound in our parish including Margaret Perrigo, Joyce Long, Connie Loebell, Mary Wallace, Steven & Anne Rampersad, Peggy Smith, Rebecca Warren-Heys, Kay Evans, Joyce Prankard, Clifford Brown, Christopher Brown, Eileen Brown, Margaret & Ted Ford, Suzanne Hosker, George Mullen, Catherine Whister, Sister Bernadette and Bernie Coleman. Welcome to all our visitors. We hope you have a lovely stay in Sidmouth. Please join us in the hall after Sunday Mass where sherry, coffee, tea and biscuits will be served to celebrate the month of Mary. For children there will be ice-cream sodas and a special Children’s Cookie Corner. This week’s Sunday Service is being broadcast by BBC radio Devon from Our Lady and St Patrick’s school in Teignmouth. Featuring Fr Mark Skelton, the head teacher Sarah Baretto,and seven children from year six talking about why and how they pray. -

“Still More Glorifyed in His Saints and Spouses”: the English Convents in Exile and the Formation of an English Catholic Identity, 1600-1800 ______

“STILL MORE GLORIFYED IN HIS SAINTS AND SPOUSES”: THE ENGLISH CONVENTS IN EXILE AND THE FORMATION OF AN ENGLISH CATHOLIC IDENTITY, 1600-1800 ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History ____________________________________ By Michelle Meza Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Gayle K. Brunelle, Chair Professor Robert McLain, Department of History Professor Nancy Fitch, Department of History Summer, 2016 ABSTRACT The English convents in exile preserved, constructed, and maintained a solid English Catholic identity in three ways: first, they preserved the past through writing the history of their convents and remembering the hardships of the English martyrs; that maintained the nuns’ continuity with their English past. Furthermore, producing obituaries of deceased nuns eulogized God’s faithful friends and provided an example to their predecessors. Second, the English nuns cultivated the present through the translation of key texts of English Catholic spirituality for use within their cloisters as well as for circulation among the wider recusant community to promote Franciscan and Ignatian spirituality. English versions of the Rule aided beginners in the convents to faithfully adhere to monastic discipline and continue on with their mission to bring English Catholicism back to England. Finally, as the English nuns looked toward the future and anticipated future needs, they used letter-writing to establish and maintain patronage networks to attract novices to their convents, obtain monetary aid in times of disaster, to secure patronage for the community and family members, and finally to establish themselves back in England in the aftermath of the French Revolution and Reign of Terror. -

Small Grants Report

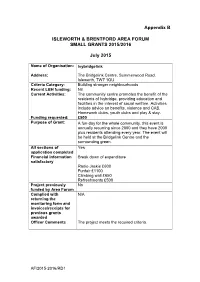

Appendix B ISLEWORTH & BRENTFORD AREA FORUM SMALL GRANTS 2015/2016 July 2015 Name of Organisation: Ivybridgelink Address: The Bridgelink Centre, Summerwood Road, Isleworth, TW7 1QU Criteria Category: Building stronger neighbourhoods Recent LBH funding: Nil Current Activities: The community centre promotes the benefit of the residents of Ivybridge, providing education and facilities in the interest of social welfare. Activities include advice on benefits, violence and CAB. Homework clubs, youth clubs and play & stay. Funding requested: £500 Purpose of Grant: A fun-day for the whole community, this event is annually recurring since 2000 and they have 2000 plus residents attending every year. The event will be held at the Bridgelink Centre and the surrounding green. All sections of Yes application completed Financial information Break down of expenditure satisfactory Radio Jackie £600 Funfair £1100 Climbing wall £650 Refreshments £500 Project previously No funded by Area Forum Complied with N/A returning the monitoring form and invoices/receipts for previous grants awarded Officer Comments The project meets the required criteria. AF/2015-2016/RD1 Name of Organisation: Our Lady of Sorrows and St Bridget’s Church Address: Memorial Square, 112 Twickenham Road, Isleworth TW7 6DL Criteria Category: Building stronger neighbourhoods Recent LBH funding: Nil Current Activities: Holding religious services such as christenings, funerals, marriages and baptisms. Hosting and helping to organise various weekly groups for disadvantaged people (including non-church members) e.g. older people, special needs, partially sighted, mental health drop-in. Funding requested: £500 Purpose of Grant: An open-air, ecumenical service of celebration and commemoration marking the 600th Anniversary of the Foundation of Syon Abbey for the Bridgettines, an order of religious people still existing today. -

Robert Adam's Revolution in Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hausberg, Miranda Jane Routh, "Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3339. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Abstract ABSTRACT ROBERT ADAM’S REVOLUTION IN ARCHITECTURE Robert Adam (1728-92) was a revolutionary artist and, unusually, he possessed the insight and bravado to self-identify as one publicly. In the first fascicle of his three-volume Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (published in installments between 1773 and 1822), he proclaimed that he had started a “revolution” in the art of architecture. Adam’s “revolution” was expansive: it comprised the introduction of avant-garde, light, and elegant architectural decoration; mastery in the design of picturesque and scenographic interiors; and a revision of Renaissance traditions, including the relegation of architectural orders, the rejection of most Palladian forms, and the embrace of the concept of taste as a foundation of architecture. -

The Comedies of George Chapman

This dissertation has been 64—11,003 microfilmed exactly as received NELSON, John Richard, 1932- THE COMEDIES OF GEORGE CHAPMAN. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1964 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE COMEDIES OF GEORGE CHAPMAN A DISSERTATION SUBOTTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JOHN RICHARD NELSON Norman, .Oklahoma 1964 THE COMEDIES OF GEORGE CHAPMAN APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COmHTTEE TABLE OF COOTEÎfTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION............................................... 1 II. THE BLIND BEGGAR OF ALEXANDRIA................................. 11 III. AN HUMOUROUS DAY’S MI R T H ...................................... 38 IV. ALL FOOLS ................................................. 73 V. MAY D A Y ................................................. 120 VI. SIR GILES GOOSECAP.............................................143 VII. THE GENTLEMANUSHER .......................................... 164 VIII. MONSIEUR D’OL I V E .............................................189 IX. THE IVIDaV'S TEARS. ........................ 208 X. CONCLUSION................ 4 " ................ 230 BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................... 234 iix THE COMEDIES OF GEORGE CHAPMAN CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The eight comedies of George Chapman (1559?-l63^)» which form the subject of this study, were written in the relatively short period of time from about 1596 to -

Sleeping and Dreaming and Their Technical Rôles in Shakespearian Drama

Durham E-Theses In the Shadow of Night: Sleeping and Dreaming and Their Technical Rôles in Shakespearian Drama KRAJNIK, FILIP How to cite: KRAJNIK, FILIP (2013) In the Shadow of Night: Sleeping and Dreaming and Their Technical Rôles in Shakespearian Drama, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7764/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 In the Shadow of Night: Sleeping and Dreaming and Their Technical Rôles in Shakespearian Drama by Filip Bul Krajník This thesis aims to demonstrate the variety of ways in which sleep and dreams are employed in Shakespeare’s dramatic canon. Using a historical perspective, the work primarily examines the functions of these motifs within the design of the plays: how they contribute to the structure and unity of the works, how they assist in delineating some of the individual characters, and how they shape the atmosphere of specific dramatic situations. -

Monasticism in the Salisbury Diocese in the Middle Ages

MONKS AND MONASTICISM DAY SCHOOL AT DOUAI ABBEY, 21 OCTOBER 2000 Professor Brian Kemp, University of Reading MONASTICISM IN THE SALISBURY DIOCESE IN THE MIDDLE AGES (in broadest sense) 1. In the Middle Ages, Berkshire formed part of the diocese of Salisbury. [This continued until 1836, when Berkshire was transferred to the diocese of Oxford] 2. Berkshire contained two of the greatest Benedictine abbeys, Abingdon and Reading, and the second of these, founded in 1121, one of the last of the Black Monk abbeys to be founded. [Reading Abbey is] located in east of the county, and in east of the diocese. I plan to focus towards the end of this talk on Reading, but before I do so – and as a prelude to set Reading in the wider context of monastic history in the diocese - I want to look at the range of religious houses available. 3. Map of English and Welsh dioceses [Pre-dissolution]. 1 4. Pre-Conquest monasteries. Male and female. [Benedictine only]. Note concentration in Dorset. Comment on paucity of female houses in Berkshire ([That in] Reading gone before 1066). Note concentration of great female houses close to Wilts / Dorset border. Note essential new start in the tenth century [known as the Tenth Century Reformation]. 2 5. Benedictine and Cluniac Male Monasteries in Dorset in Middle Ages. (Cluniac [was a] reformed, rich and grand form of Benedictine) Holme [was] founded c. 1150 as daughter house of Montacute [Somerset]. Otherwise all pre-Conquest, but note vicissitudes of: a) Cranbourne, moved in 1102 to Tewkesbury [Gloucestershire]; b) Sherborne, cathedral until 1075/8, after which subordinated as a priory to Salisbury, 1122 restored as an abbey; c) Horton, reduced to priory status in 1122 x 39 and annexed to Sherborne 3 6. -

English Carthusian Martyrs (PDF)

The Life and Times of the English Carthusian Martyrs by Rev. Dr. Anselm J. Gribbin & John Paul Kirkham © Anselm Gribbin & John Paul Kirkham All rights reserved First published 2020 1st Edition Cover image: Martyrdom of The English Carthusians by Jan Kalinski Contents 1. Introduction 2. St. Bruno – Founder of the Carthusians and Master of the Wilderness 3. The English Carthusian Martyrs and Aftermath 4. The Eighteen English Carthusian Martyrs 5. Carthusian Spirituality and Prayers 6. Carthusian Houses in the UK – Past and Present 7. Recommended Reading, Further Information and Final Reflection Introduction Our life shows that the good from heaven is already to be found on earth; it is a precursor of the resurrection and like an anticipation of a renewed world. (Carthusian Statutes 34.3) If a survey were to be conducted today in which people were asked about their knowledge of monastic life, they would probably say that the abbeys and monasteries in which nuns and monks live are to be found hidden away in the countryside in quiet places far away from modern cities. Although this is quite true in most cases, there are many religious who strive to live the monastic life in the heart of a city or other urban surroundings. Good examples would include the Tyburn Nuns in Marble Arch, London, the Carmelite Monastery, Allerton in the city of Liverpool or the gargantuan Monastery of The Holy Cross in Chicago. We might be inclined to think that “urban monasticism” is a purely modern invention, but would be wrong in doing so because many monasteries in medieval England were situated in or near cities and towns, both by accident and design.