Indonesia Cluster Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kajian Tipe Penggunaan Lahan Di Kecamatan Sei Bingai Kabupaten Langkat Sumatera Utara

i KAJIAN TIPE PENGGUNAAN LAHAN DI KECAMATAN SEI BINGAI KABUPATEN LANGKAT SUMATERA UTARA SKRIPSI MUHAMMAD IDDHIAN 141201096 DEPARTEMEN MANAJEMEN HUTAN FAKULTAS KEHUTANAN UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA 2018 i Universitas Sumatera Utara ii KAJIAN TIPE PENGGUNAAN LAHAN DI KECAMATAN SEI BINGAI KABUPATEN LANGKAT SUMATERA UTARA SKRIPSI OLEH: MUHAMMAD IDDHIAN 141201096 DEPARTEMEN MANAJEMEN HUTAN FAKULTAS KEHUTANAN UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA 2018 ii Universitas Sumatera Utara iii KAJIAN TIPE PENGGUNAAN LAHAN DI KECAMATAN SEI BINGAI KABUPATEN LANGKAT SUMATERA UTARA SKRIPSI Oleh: MUHAMMAD IDDHIAN 141201096 Skripsi sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Kehutanan di Fakultas Kehutanan Universitas Sumatera Utara DEPARTEMEN MANAJEMEN HUTAN FAKULTAS KEHUTANAN UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA 2018 iii Universitas Sumatera Utara iv iv Universitas Sumatera Utara v ABSTRACT MUHAMMAD IDDHIAN: Land Use Type Study in Sei Bingai sub-District Langkat District North Sumatera, supervised by RAHMAWATY and ABDUL RAUF. Land evaluation is important to be done to determine the suitability between the quality and characteristics of the land with the requirements requested by the type of land use. This study aimed to identify the type of land usage based on land utilitization characteristics. The method of this study was matching the quality and characteristics of the land with the conditions of land unit on 10 units of land in the villages, namely: Telagah, Rumah Galuh, Kuta Buluh and Gunung Ambat. The results of evaluating the best land usage were animal feed production and agriculture with the heaviest limiting factor: slope and texture. Agriculture was the best alternative choice according to the community of Sei Bingai sub-District by prioritizing education factors in these criteria. -

Strategi Pengembangan Wilayah Dalam Kaitannya Dengan Disparitas Pembangunan Antar Kecamatan Di Kabupaten Langkat

STRATEGI PENGEMBANGAN WILAYAH DALAM KAITANNYA DENGAN DISPARITAS PEMBANGUNAN ANTAR KECAMATAN DI KABUPATEN LANGKAT TESIS Oleh ROULI MARIA MANALU 127003018/PWD SEKOLAH PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA M E D A N 2015 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA STRATEGI PENGEMBANGAN WILAYAH DALAM KAITANNYA DENGAN DISPARITAS PEMBANGUNAN ANTAR KECAMATAN DI KABUPATEN LANGKAT TESIS Diajukan Sebagai Salah Satu Syarat untuk Memperoleh Gelar Magister Sains dalam Program Studi Perencanaan Pembangunan Wilayah dan Pedesaan pada Sekolah Pascasarjana Universitas Sumatera Utara Oleh ROULI MARIA MANALU 127003018/PWD SEKOLAH PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA M E D A N 2015 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Judul : STRATEGI PENGEMBANGAN WILAYAH DALAM KAITANNYA DENGAN DISPARITAS PEMBANGUNAN ANTAR KECAMATAN DI KABUPATEN LANGKAT Nama Mahasiswa : ROULI MARIA MANALU NIM : 127003018 Program Studi : Perencanaan Pembangunan Wilayah dan Pedesaan (PWD) Menyetujui, Komisi Pembimbing Dr. Rujiman, MA Dr. Irsyad Lubis M.Sos, Sc Ketua Anggota Ketua Program Studi, Direktur, Prof. Dr. lic. rer. reg. Sirojuzilam, SE Prof. Dr. Erman Munir, M. Sc Tanggal Lulus: 9 Mei 2015 Telah diuji UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Pada tanggal: 9 Mei 2015 PANITIA PENGUJI TESIS: Ketua : Dr. Rujiman, MA Anggota : 1. Dr. Irsyad Lubis, M.Sos, Sc 2. Prof. Dr. lic. rer. reg. Sirojuzilam, SE 3. Kasyful Mahalli, SE, M.Si 4. Dr. Agus Purwoko, S.Hut, M.Si PERNYATAAN UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA STRATEGI PENGEMBANGAN WILAYAH DALAM KAITANNYA DENGAN DISPARITAS PEMBANGUNAN ANTAR KECAMATAN DI KABUPATEN LANGKAT TESIS Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa dalam tesis ini tidak terdapat karya yang pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh gelar kesarjanaan di suatu perguruan tinggi, dan sepanjang pengetahuan saya juga tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang pernah ditulis atau diterbitkan oleh orang lain , kecuali yang secara tertulis diacu dalam naskah ini dan disebutkan dalam daftar pustaka. -

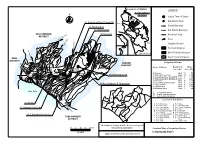

LEGEND N Irrigation Scheme Location Map of Irrigation Schemes

Location of District LEGEND NORTH SUMATRA N PROVINCE Capital Town of District MEDAN Sub-District Town 28. Penambean/Panet Tongah BK ACEH District Boundary 47. Bah Korah II Lake Toba 32. Naga Sompah Sub-District Boundary DELI SERDANG 30. Karasaan Provincial Road DISTRICT Ke Tebing Tinggi River RIAU Irrigation Scheme Ke Tebing Tinggi Technical Irrigation Negeri Dolok Perdagangan Ke Tebing Tinggi WEST SUMATRA Semi-Technical Irrigation Non-Technical Irrigation KARO Sinar Raya Ke Bangun Purba Bangun Ke Kampung Tengah DISTRICT Irrigation Scheme Saran Panlang Sinaksak ASAHAN DISTRICT SIMALUNGUN Name of Scheme Registered Subject Pematang Area (Ha) Area (Ha) DISTRICT Siantar Pematang Dolok Sigalang Raya Pematang 26. Pentara 1,034 ST 298 Tanah Jawa 49. Rambung Merah 27. Simanten Pane Dame 1,000 NT 1,000 28. Penambean/Panet Tongah BK 1,723 T 1,722 Tiga Runggu PEMATANG 29. Raja Hombang/T. Manganraja 2,045 T 2,023 Sipintu Angin SIANTAR 30. Kerasaan 5,000 T 4,144 29. Raja Hombang/ T. Manganraja 31. Javacolonisasi/Purbogondo 1,030 T 1,015 32. Naga Sompah 1,360 T 1,015 47. Bah Korah II 1,995 T 1,723 49. Rambung Mera 1,104 T 944 F Lake Toba C T : Technical Irrigation E ST : Semi-Technical Irrigation D G NT : Non-Technical Irrigation B I U H Location of Sub-District 26. Pentara A K L M A Kec. Silima Kuta K Kec. Siantar B Kec. Dolok Silau Kec. Huta bayu Raja Ke Porsea J O M 27. Simantin Pane Dame C Kec. Silau Kahean N Kec. Dolok Pardamean N D Kec. -

Profil Kabupaten Langkat

@TA.2016 Bab 2 Profil Kabupaten Langkat 2.1. Wilayah Administrasi 2.1.1. Luas dan Batas Wilayah Administratif Luas wilayah Kabupaten Langkat adalah 6.263,29 km² atau 626.329 Ha, sekitar 8,74% dari luas wilayah Provinsi Sumatera Utara. Kabupaten Langkat terbagi dalam 3 Wilayah Pembangunan (WP) yaitu ; Langkat Hulu seluas 211.029 ha., wilayah ini meliputi Kecamatan Bahorok, Kutambaru, Salapian, Sirapit, Kuala, Sei Bingai, Selesai dan Binjai. Langkat Hilir seluas 250.761 ha. wilayah ini meliputi Kecamatan Stabat, Wampu, Secanggang, Hinai, Batang Serangan, Sawit Seberang, Padang Tualang dan Tanjung Pura. Teluk Aru seluas 164.539 ha. wilayah ini meliputi Kecamatan Gebang, Babalan, Sei Lepan, Brandan Barat, Pangkalan Susu, Besitang dan Pematang Jaya. Secara administratif, Kabupaten Langkat terdiri atas 23 wilayah kecamatan, 240 desa, dan 37 kelurahan. Kecamatan dengan wilayah paling luas adalah Kecamatan Batang Serangan (93,490 ha), dan yang paling sempit adalah Kecamatan Binjai (4,955 ha). Kecamatan dengan Desa terbanyak adalah Kecamatan Bahorok dan Kecamatan Tanjung Pura (19 desa/kelurahan) sedangkan kecamatan dengan desa/kelurahan paling sedikit adalah Kecamatan Sawit Seberang, Brandan Barat dan Binjai (7 Desa/Kelurahan). II-1 | P a g e Bantuan Teknis Rencana Program Investasi Jangka Menengah Kabupaten Langkat @TA.2016 Tabel 2.1 Pembagian Wilayah Administrasi dan Luas Wilayah. Banyaknya Luas No. Kecamatan Ibu Kecamatan Desa Kelurahan Km² % (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) 1 Bahorok Pkn Bahorok 18 1 1.101,83 17,59 2 Sirapit Sidorejo 10 0 98,5 1,57 3 Salapian Minta Kasih 16 1 221,73 3,54 4 Kutambaru Kutambaru 8 0 234,84 3,78 5 Sei Bingei Namu Ukur Sltn 15 1 333,17 5,32 6 Kuala Pkn Kuala 14 2 206,23 3,29 7 Selesai Pkn Selesai 13 1 167,73 2,68 8 Binjai Kwala Begumit 6 1 42,05 0.67 9. -

N. KABUPATEN LANGKAT I. PROFIL DAERAH Kondisi Geografis Kabupaten Langkat Merupakan Salah Satu Daerah Yang Berada Di

N. KABUPATEN LANGKAT I. PROFIL DAERAH Kondisi Geografis Kabupaten Langkat merupakan salah satu daerah yang berada di Sumatera Utara. Secara geografis Kabupaten Langkat berada pada 3°14’00”– 4°13’00” Lintang Utara, 97°52’00’ – 98° 45’00” Bujur Timur dan 4 – 105 m dari permukaan laut. Kabupaten Langkat menempati area seluas ± 6.263,29 Km2 (626.329 Ha) yang terdiri dari 23 Kecamatan dan 240 Desa serta 37 Kelurahan Definitif. Area Kabupaten Langkat memiliki batas-batas wilayah antara lain: • Utara : berbatasan dengan Provinsi Aceh dan Selat Malaka • Selatan: berbatasan dengan Kabupaten Karo • Barat : berbatasan dengan Provinsi Aceh • Timur : berbatasan dengan Kabupaten Deli Serdang dan Kota Binjai Seperti daerah‐daerah lainnya yang berada di kawasan Sumatera Utara, Kabupaten Langkat termasuk daerah yang beriklim tropis. Sehingga daerah ini memiliki 2 musim yaitu musim kemarau dan musim hujan. Musim kemarau dan musim hujan biasanya ditandai dengan sedikit banyaknya hari hujan dan volume curah hujan pada bulan terjadinya musim. Iklim di wilayah Kabupaten Langkat termasuk tropis dengan indikator iklim sebagai berikut : Musim Kemarau (Februari s/d Agustus); Musim Hujan (September s/d Januari). Curah hujan rata-rata 2.205,43 mm/tahun dengan suhu rata-rata 28 derajat celcius - 30 derajat celcius. Kabupaten Langkat memiliki 23 Kecamatan dimana kecamatan luas daerah terbesar adalah kecamatan Bahorok dengan luas 1.101,83 km2 atau 17,59 persen diikuti kecamatan Batang Serangan dengan luas 899,38 km2 atau 14,36 persen. Sedangkan luas daerah terkecil adalah kecamatan Binjai Penelitian KPJU Unggulan UMKM Provinsi Sumatera Utara Tahun 2018 III-398 dengan luas 42,05 km2 atau 0,67 persen dari total luas wilayah Kabupaten Langkat. -

ASSESSMENT REPORT Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil

PT. MUTUAGUNG LESTARI ASSESSMENT REPORT Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil Certification R S P O [ ]Stage-1 [√] Stage-2 [ ] Surveillance-02 [ ] Re-Certification Name of Management : Stabat POM – PT. Langkat Nusantara Kepong, subsidiary of Kuala Organisation Lumpur Kepong Bhd Plantation Name : PT. Langkat Nusantara Kepong Location Gohor Lama Village, Sub District of Wampu, Langkat Regent, Province of North Sumatra, Indonesia Certificate Code : MUTU-RSPO/095 Date of Certificate Issue : 4 August 2017 Date of License Issue : 4 August 2017 Date of Certificate Expiry : 3 August 2022 Date of License Expiry : 3 August 2018 Assessment PT. Mutuagung Lestari Reviewed Approved Assessment Date Auditor by by Sandra Purba (LA), Yuniar Mitikauji, Dwi 29 August – 1 September ST - 1 Haryati, Arif Faisal 2016 Ganapathy Tony Sandra Purba (LA), Ardiansyah, Moh Arif Ramasamy Arifiarachman ST - 2 13 – 17 December 2016 Yusni, Leonada, Yohanes Hardian Assessment Approved by MUTUAGUNG LESTARI on: ST - 2 4 August 2017 PT Mutuagung Lestari • Raya Bogor Km 33,5 Number 19 • Cimanggis • Depok 16953 • Indonesia Telephone (+62) (21) 8740202 • Fax (+62) (21) 87740745/6 • Email: [email protected] • www.mutucertification.com MUTU Certification • Accredited by Accreditation Services International on March 12th, 2014 with registration number RSPO-ACC-007 PT MUTUAGUNG LESTARI ASSESSMENT REPORT TABLE OF CONTENT FIGURE ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Javanese Vs Malays

Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford The Orang Melayu and Orang Jawa in the ‘Lands Below the Winds’ Riwanto Tirtosudarmo CRISE WORKING PAPER 14 March 2005 Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity (CRISE) Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford, 21 St Giles, Oxford OX1 3LA, UK Tel: +44 1865 283078 · Fax: +44 1865 273607 · www.crise.ox.ac.uk CRISE Working Paper No.14 Abstract This paper is concerned with the historical development of two supposedly dominant ethnic groups: the Javanese in Indonesia and the Malay in Malaysia. Malaysia and Indonesia constitute the core of the Malay world. Through reading the relevant historical and contemporary literature, this essay attempts to shed some light on the overlapping histories of these two cultural identities since long before the arrival of the Europeans. The two were part of the same fluid ethnic community prior to the arrival of the Europeans in this ‘land below the winds’. The contest among the Europeans to control the region resulted in the parcelling of the region into separated colonial states, transforming the previously fluid and shifting ethnic boundaries into more rigid and exclusive ethnic identities. In the process of nation-formation in Malaysia, Malay-ness was consciously manipulated by the colonial and post-colonial elites to define and formulate the Malaysian state and its ideology. The Javanese, on the other hand, though demographically constituting the majority group in Indonesia, paradoxically melded into the political background as the first generation of Indonesian leaders moved toward a more trans-ethnic nationalism – Indonesian civic nationalism. Indeed, when comparing ‘ethnicity and its related issues’ in Malaysia and Indonesia, fundamental differences in the trajectories of their ‘national’ histories and political developments should not be overlooked. -

Infobencana Kabupatenlangkat

I N F O B E N C A N A K A B U P A T E N L A N G K A T EDISI TRIWULAN I BULAN JANUARI, FEBRUARI DAN MARET 2013 Dalam edisi ini : - Sorotan. - 3.964 KK terendam banjir di Kecamatan Hinai dan Tanjung Pura. - Upaya Penanganan Bencana yang di lakukan. SOROTAN Selama triwulan I tahun 2013 tercatat bencana alam hidrometrologi berupa banjir, tanah longsor, angin puting beliung melanda daerah / Kabupaten Langkat dan beberapa Banjir di Kecamatan Hinai pada Februari 2013, yang bencana ( non alam ) yaitu kebakaran yang di akibatkan dari merendam Pemukiman warga sebanyak 1085 KK kelalaian masyarakat itu sendiri. Bencana alam hidrometrologi berupa banjir yang terjadi mengakibatkan sejumlah pemukiman penduduk di daerah Kecamatan Hinai 1085 KK dan Kec. Tanjung Pura 2879 KK terendam air dan beberapa lahan pertanian rusak namun tidak ada korban jiwa. Longsor terjadi di daerah Kecamatan Sei Bingai dan Kecamatan Kutambaru mengakibatkan jembatan dan ruas badan jalan rusak sehingga mengakibatkan lumpuhnya jalur transportasi antar Kecamatan di Daerah tersebut. Begitu juga dengan angin puting beliung terjadi di daerah Peninjauan Langsung Bupati Langkat Kecamatan Salapian yang mengakibatkan pemukiman penduduk Bpk. H. Ngogesa Sitepu, SH pada saat bencana banjir 2 rumah rusak berat dan 12 rumah rusak sedang 10 rumah rusak di Kecamatan Hinai pada Februari 2013 ringan dan tidak ada korban jiwa. Di triwulan I tahun 2013 tercatat bencana non alam ( kebakaran ) sangat dominan terjadi sebanyak 10 ( sepuluh ) kali di daerah Kabupaten Langkat diantaranya ; Kecamatan Babalan -

Tural Phenomenon of Monument Building in Batak Toba People Life in Pangururan District and Palipi District Samosir

Tural phenomenon of Monument Building in Batak Toba People Life in Pangururan District and Palipi District Samosir Ulung Napitu1, Corry1, Resna Napitu2, Supsiloani3 1History Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Universitas Simalungun, Indonesia 2Management Study Program, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Simalungun, Indonesia 3Anthropology Study Program, Universitas Negeri Medan, Indonesia [email protected] Keywords Abstract phenomenon; culture; This study aims to analyze the phenomenon of monument monument; Batak tribe; building culture in the life of Toba Batak tribe in Pangururan Indonesia and Palipi Districts, Samosir Regency. This research uses descriptive analytic method with phenomenology approach. The phenomenological approach is a tradition of qualitative research that is rooted in philosophical and psychological, and focuses on the experience of human life (sociology). The results of this study indicate that the cultural phenomenon of monument building in the life of Toba Batak community is a form of cultural activity carried out by Toba Batak tribe as a tribute to the spirits of the ancestors or to the Ompu-Ompu, on the basis of religion and tradition that are still alive until now. This is Toba Batak tribe who highly respects the spirits of their ancestors. I. Introduction The socio-cultural phenomenon experienced by the community is universally also found in the lives of Toba Bataks. Religious systems and socio-cultural values whose roots are the same, but in terms of their implementation are determined and influenced by the cognition, perception and social environment of each ethnic group. Toba Batak tribe from ancient times until today still retains the traditional values inherited from their ancestors, although sometimes they are contrary to religious teachings but are still maintained. -

Notions of Critical Thinking in Javanese, Batak Toba and Minangkabau Culture Julia Suleeman Chandra University of Indonesia

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Papers from the International Association for Cross- IACCP Cultural Psychology Conferences 2004 Notions of Critical Thinking in Javanese, Batak Toba and Minangkabau Culture Julia Suleeman Chandra University of Indonesia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Chandra, J. S. (2004). Notions of critical thinking in Javanese, Batak Toba and Minangkabau culture. In B. N. Setiadi, A. Supratiknya, W. J. Lonner, & Y. H. Poortinga (Eds.), Ongoing themes in psychology and culture: Proceedings from the 16th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/258 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IACCP at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology Conferences by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 275 NOTIONS OF CRITICAL TIDNKING IN JAVANESE, BATAK TOBA AND MINANGKABAU CULTURE Julia Suleeman Chandra University of Indonesia Jakarta, Indonesia Studies from researchers with Western academic background (e.g., Blanchard & Clanchy, 1984; Freedman, 1994) show that Asian students, including Indonesians, have difficulties to think critically, i.e., to argue and to develop one's own opinion. Despite our limited knowledge on the processes and mechanisms underlying thinking in general (Riding & Powell, 1993), the term critical thinking refers to " ... an investigation whose pur pose is to explore a situation, phenomenon, question, or problem to arrive at a hypothesis or conclusion about it that integrates all available informa tion and that can therefore be convincingly justified' (Kurfiss, 1988, p. -

Gondang Sabangunan Among the Protestant Toba Batak People in the 1990S *

Gondang Sabangunan among the Protestant Toba Batak People in the 1990s * Mauly Purba This article is a study of the changes that have occurred in the uses, functions, meanings, musical style and performance dynamics of gondang sabangunan, the ceremonial music of the Toba Batak people of North Sumatra, and its associated tortor dancing as a result of the large- scale conversion of the people to Christianity. In pre-Christian times (before the 1860s), the performance of gondang-tortor was a form of religious observance based on specific rules, and as such was an integral part of the social and religious code known as adat. Changes in the religious and political orientation of Toba society in the period between the 1860s and the end of the twentieth century resulted in changes of style and meaning in ritual performances such as gondang sabangunan. For more than thirteen decades now the church has controlled the Christian Tobas’ ritual performance practices. When, after almost a century of conflict between the missionaries and their congregants, the Protestant church promulgated a new approach to performing gondang and tortor in adat and church feasts, as recorded in its 1952 Order of Discipline, its intention was to minimise the practice of spirit beliefs and unify the Protestants’ way of using the gondang-tortor tradition.1 This and the subsequent 1968 and 1987 Orders of Discipline of the Huria Kristen Batak Protestant (Batak Protestant Christian Church [HKBP]) and the 1982 Order of Discipline of the Gereja Kristen Protestant Indonesia (Protestant Christian Indonesian Church [GKPI]), aimed to de-contextualise the practice of gondang and tortor from * This article draws on research undertaken at Monash University, Melbourne, for my PhD thesis, Musical and Functional Change in the Gondang Sabangunan Tradition of the Protestant Toba Batak 1860s–1990s with particular reference to 1980s–1990s, (Monash University, 1999).