Breaking Points: Mutiny in the Continental Army Joseph St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mutinies of 1781

THE MUTINIES OF 1781 Two mutinies of Continental Line troops occurred in January 1781 as a consequence of a lack of food, spirits, clothing, and pay for at least a year. While these harsh conditions were not unique for that time, the first mutiny led to but only a second that was dramatically quelled in short order. Six reGiments of the Pennsylvania Line were winter-quartered south of Morristown, New Jersey, under the command of General Anthony Wayne. On New Year’s Day, January 1, 1781, soldiers from the regiments of the Line mutinied to seek redress for their sufferinG state. DurinG the initial uprisinG, two officers, a Lieutenant White and Captain Samuel Tolbert, were seriously wounded, with a third, Captain Alan BittinG/Bettin of the 4th Regiment, killed. After taking a cannon, the mutineers marched directly to Princeton to air their grievances. There, a board of sergeants was selected, headed by Sergeant William Bouzar, which then met with the President of the Supreme Executive Council of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Joseph Reed. Following the initial meeting, Reed met with delegates of the Continental Congress at Trenton. Reed seems to have found their demands compellinG. Subsequently, the troop marched to Trenton for a continuation of the neGotiations. There, a Commission was created to consider mainly their one complaint concerning bounties paid out to enlistees in 1776 and 1777. Following the Commission’s review, immediate discharges were Granted to those three-year men whose enlistments were over. Each was promised partial payment of back pay in addition to items of need. -

Starving Soldiers: Joseph Plumb Martin

1 Revolutionary War Unit Starving Soldiers: Joseph Plumb Martin TIME AND GRADE LEVEL One 45 or 50 minute class period in a Grade 4-8. PURPOSE AND CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT QUESTIONS History is the chronicle of choices made by actors/agents/protagonists who, in very specific contexts, unearth opportunities and inevitably encounter impediments. During the Revolutionary War people of every stripe navigated turbulent waters. As individuals and groups struggled for their own survival, they also shaped the course of the nation. Whether a general or a private, male or female, free or enslaved, each became a player in a sweeping drama. The instructive sessions outlined here are tailored for upper elementary and middle school students, who encounter history most readily through the lives of individual historical players. Here, students actually become those players, confronted with tough and often heart-wrenching choices that have significant consequences. History in all its complexity comes alive. It is a convoluted, thorny business, far more so than streamlined timelines suggest, yet still accessible on a personal level to students at this level. In this simulation, elementary or middle school students become privates in the Continental Army who are not receiving adequate rations. It is spring of 1780, and they have just survived the coldest winter in recorded history on the mid-Atlantic East Coast, with no food for days on end— but food is still scant, even after the weather has warmed. They want to register their complaint, but how forcibly should they do so? Should they resort to extreme measures, like mutiny or desertion? What might they do short of that? Students placed in this situation will be able to internalize hardships faced by common soldiers in the Revolutionary War. -

Philadelphia, the Indispensable City of the American Founding the FPRI Ginsburg—Satell Lecture 2020 Colonial Philadelphia

Philadelphia, the Indispensable City of the American Founding The FPRI Ginsburg—Satell Lecture 2020 Colonial Philadelphia Though its population was only 35,000 to 40,000 around 1776 Philadelphia was the largest city in North America and the second-largest English- speaking city in the world! Its harbor and central location made it a natural crossroads for the 13 British colonies. Its population was also unusually diverse, since the original Quaker colonists had become a dwindling minority among other English, Scottish, and Welsh inhabitants, a large admixture of Germans, plus French Huguenots, Dutchmen, and Sephardic Jews. But Beware of Prolepsis! Despite the city’s key position its centrality to the American Revolution was by no means inevitable. For that matter, American independence itself was by no means inevitable. For instance, William Penn (above) and Benjamin Franklin (below) were both ardent imperial patriots. We learned of Franklin’s loyalty to King George III last time…. Benjamin Franklin … … and the Crisis of the British Empire The FPRI Ginsburg-Satell Lecture 2019 The First Continental Congress met at Carpenters Hall in Philadelphia where representatives of 12 of the colonies met to protest Parliament’s Coercive Acts, deemed “Intolerable” by Americans. But Congress (narrowly) rejected the Galloway Plan under which Americans would form their own legislature and tax themselves on behalf of the British crown. Hence, “no taxation without representation” wasn’t really the issue. WHAT IF… The Redcoats had won the Battle of Bunker Hill (left)? The Continental Army had not escaped capture on Long Island (right)? Washington had been shot at the Battle of Brandywine (left)? Or dared not undertake the risky Yorktown campaign (right)? Why did King Charles II grant William Penn a charter for a New World colony nearly as large as England itself? Nobody knows, but his intention was to found a Quaker colony dedicated to peace, religious toleration, and prosperity. -

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

HMM Richards, Litt. D

‘ R HAR M . C D L H M . S D . I , ITT . ADDR ESS DELIVER ED AT VALLEY FOR GE AT THE N N ' L M IN G OF THE SO I Y A A EET C ET , N V MB R 2 O 1 1 6 . E E , 9 LA A ER N C ST , PA. I 9 I 7 VALLEY FORGE AN D THE PENNSYLVAN IA GERMANS. O~ DAY our feet' rest o n ground w hich has been m a d e h o l y t h r o u g h t h e suff ering of men who endu red mu ch so that m i ht en we , coming after them , g joy the bles sings of freedom in a free country . The battle of Bra ndywine had been fou ght and lost ; a delu ge of rain pre vented a su cceeding engagement at u the Warren Tavern , and an nforeseen fog robbed the - American Army of a hoped for Victory at Germantown . F u u s l shed with s cces , and in all their showy panoply of war , the Briti s h and Hessian troops had marched into Phila ' o f - F us d h a hoped for Victory at Germantown . l he wit u the s ccess , and in all their showy panoply of war, British and Hessian troops had marched into Phila 3 The P enns lva nia - Germ a n o cie t y S y . d elphia , the capital city of the nation , behind their ex u u ulting m sic , to find for themselves lux rious quarters , i er with abundance of supplies , for the com ng w mt . -

Continental Army: Valley Forge Encampment

REFERENCES HISTORICAL REGISTRY OF OFFICERS OF THE CONTINENTAL ARMY T.B. HEITMAN CONTINENTAL ARMY R. WRIGHT BIRTHPLACE OF AN ARMY J.B. TRUSSELL SINEWS OF INDEPENDENCE CHARLES LESSER THESIS OF OFFICER ATTRITION J. SCHNARENBERG ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION M. BOATNER PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN D. MARTIN AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE DELAWARE VALLEY E. GIFFORD VALLEY FORGE J.W. JACKSON PENNSYLVANIA LINE J.B. TRUSSELL GEORGE WASHINGTON WAR ROBERT LECKIE ENCYLOPEDIA OF CONTINENTAL F.A. BERG ARMY UNITS VALLEY FORGE PARK MICROFILM Continental Army at Valley Forge GEN GEORGE WASHINGTON Division: FIRST DIVISION MG CHARLES LEE SECOND DIVISION MG THOMAS MIFFLIN THIRD DIVISION MG MARQUES DE LAFAYETTE FOURTH DIVISION MG BARON DEKALB FIFTH DIVISION MG LORD STIRLING ARTILLERY BG HENRY KNOX CAVALRY BG CASIMIR PULASKI NJ BRIGADE BG WILLIAM MAXWELL Divisions were loosly organized during the encampment. Reorganization in May and JUNE set these Divisions as shown. KNOX'S ARTILLERY arrived Valley Forge JAN 1778 CAVALRY arrived Valley Forge DEC 1777 and left the same month. NJ BRIGADE departed Valley Forge in MAY and rejoined LEE'S FIRST DIVISION at MONMOUTH. Previous Division Commanders were; MG NATHANIEL GREENE, MG JOHN SULLIVAN, MG ALEXANDER MCDOUGEL MONTHLY STRENGTH REPORTS ALTERATIONS Month Fit For Duty Assigned Died Desert Disch Enlist DEC 12501 14892 88 129 25 74 JAN 7950 18197 0 0 0 0 FEB 6264 19264 209 147 925 240 MAR 5642 18268 399 181 261 193 APR 10826 19055 384 188 116 1279 MAY 13321 21802 374 227 170 1004 JUN 13751 22309 220 96 112 924 Totals: 70255 133787 1674 968 1609 3714 Ref: C.M. -

Nh Revolutionary War Burials

Revolutionary Graves of New Hampshire NAME BORN PLACE OF BIRTH DIED PLACE OF DEATH MARRIED FATHER BURIED TOWN CEMETERY OCCUPATION SERVICE PENSION SOURCE Abbott, Benjamin February 10, 1750 Concord, NH December 11, 1815 Concord, NH Sarah Brown Concord Old North Cemetery Hutchinson Company; Stark Regt. Abbott, Benjamin April 12, 1740 1837 Hollis, NH Benjamin Hollis Church Cemetery Dow's Minutemen; Pvt. Ticonderoga Abbott, Jeremiah March 17, 1744 November 8, 1823 Conway, NH Conway Conway Village Cemetery Bunker Hill; Lieut. NH Cont. Army Abbott, Joseph Alfie Brainard Nathaniel Rumney West Cemetery Col Nichols Regt. Abbott, Josiah 1760 February 12, 1837 Colebrook, NH Anna Colebrook Village Cemetery Col. B. Tupper Regt.;Lieut. Abbott, Nathaniel G. May 10, 1814 Rumney, NH Rumney Village Cemetery John Stark Regiment Adams, David January 24, 1838 Derry, NH Derry Forest Hill James Reed Regt. Adams, Ebenezer 1832 Barnstead, NH Barnstead Adams Graveyard, Province Road Capt. C. Hodgdon Co. Adams, Edmund January 18, 1825 Derry, NH Derry Forest Hill John Moody Company Adams, Joel 1749 1828 Sharon, NH Sharon Jamany Hill Cemetery Adams, John May 8, 1830 Sutton, NH Sutton South Cemetery Col. J. Reid Regt. Adams, John Barnstead Aiken Graveyard Capt. N. Brown Co. Adams, John Jr. September 29, 1749 Rowley, MA March 15, 1821 New London, NH New London Old Main Street Cemetery Adams, Jonathan March 20, 1820 Derry, NH Derry Forest Hill John Bell Regt. Adams, Moses c1726 Sherborn, MA June 4, 1810 Dublin, NH Hepzibah Death/Mary Russell Swan Dublin Old Town Cemetery Capt. In NH Militia Adams, Solomon March 4, 1759 Rowley, MA March 1834 New London, NH Mary Bancroft New London Old Main Street Cemetery Saratoga Adams, Stephen 1746 Hamilton, MA October 1819 Meredith, NH Jane Meredith Swasey Graveyard Massachusetts Line Adams, William October 5, 1828 Derry, NH Derry Forest Hill Col. -

Voyages of Two Philadelphia Ships

The William and Favorite: The "Post-Revolutionary "Voyages of Two Philadelphia Ships AFTER the Revolution, American merchants worked to replace /\ hazardous wartime ventures with more stable and profitable JL JL, trades. Parliament allowed United States vessels the same privileges as English vessels when trading in Great Britain, but it prohibited their entry into colonial ports, as did several other nations. Thus, American merchants accustomed to purchasing British goods with profits from West Indian markets before the war now faced new obstacles to their former trades. One Philadelphia mercantile house, Stewart, Nesbitt & Co., used two of their ships acquired in wartime to experiment with promising peacetime oppor- tunities. A brief examination of their experiences offers a good sampling of the ways Americans tried to adapt to the changing commercial patterns and trade restrictions of the post-Revolutionary decade.1 Stewart, Nesbitt & Co. was organized in 1782 by two Philadel- phians of Irish birth. Walter Stewart was a young handsome army colonel who had just married the daughter of the city's leading investor in privateers, Blair McClenachan. Stewart's energy and new financial resources helped him convince his close friend, Alex- ander Nesbitt, to accept him as a business partner. Nesbitt, who had established himself before the war, invested mostly in letters of marque bound for West Indian and French ports, but he was also 1 The papers of Stewart, Nesbitt & Co., hitherto unexamined, are located in the library of the Mariner's Museum in Newport News, Virginia. Consisting of more than 600 letters, plus thousands of receipts and accounts, the correspondence is limited to letters received by the company and many of the business papers are undated, leaving time gaps in all the financial records. -

201-250-The-Constitution.Pdf

Note Cards 201. Newburgh Conspiracy The officers of the Continental Army had long gone without pay, and they met in Newburgh, New York to address Congress about their pay. Unfortunately, the American government had little money after the Revolutionary War. They also considered staging a coup and seizing control of the new government, but the plotting ceased when George Washington refused to support the plan. 202. Articles of Confederation: powers, weaknesses, successes The Articles of Confederation delegated most of the powers (the power to tax, to regulate trade, and to draft troops) to the individual states, but left the federal government power over war, foreign policy, and issuing money. The Articles’ weakness was that they gave the federal government so little power that it couldn’t keep the country united. The Articles’ only major success was that they settled western land claims with the Northwest Ordinance. The Articles were abandoned for the Constitution. 203. Constitution The document which established the present federal government of the United States and outlined its powers. It can be changed through amendments. 204. Constitution: Preamble "We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America." 205. Constitution: Legislature One of the three branches of government, the legislature makes laws. There are two parts to the legislature: the House of Representatives and the Senate. -

The Battle of Saratoga to the Paris Peace Treaty

1 Matt Gillespie 12/17/03 A&HW 4036 Unit: Colonial America and the American Revolution. Lesson: The Battle of Saratoga to the Paris Peace Treaty. AIM: Why was the American victory at the Saratoga Campaign important for the American Revolution? Goals/Objectives: 1. Given factual data about the Battle of Saratoga and the Battle of Yorktown, students will be able to describe the particular events of the battles and how the Americans were able to win each battle. 2. Students will be able to recognize and explain why the battles were significant in the context of the entire war. (For example, the Battle of Saratoga indirectly leads to French assistance.) 3. Students will be able to read and interpret a key political document, The Paris peace Treaty of 1783. 4. Students will investigate key turning points in US history and explain why these events are significant. Students will be able to make arguments as to why these two battles were turning points in American history. (NYS 1.4) 5. Given the information, students will understand their historical roots and be able to reconstruct the past. Students will be able to realize how victory in these battles enabled the paris Peace Treaty to come about. (NCSS II) Main Ideas: • The campaign consists of three major conflicts. 1) The Battle of Freeman’s farm. 2) Battle of Bennington. 3) Battle of Bemis Heights. • Battle of Bennington took place on Aug. 16-17th, 1777. Burgoyne sent out Baum to take American stores at Bennington. General Stark won. • Freeman’s farm was on Sept. -

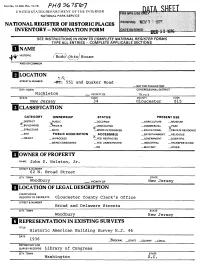

Hclassifi Cation

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) P f~f (J) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ iNAME /•—'——""•% HISTORIC ( BodoVOtto/ House AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER HRtr. 551 and Quaker Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Mickleton __ VICINITY OF "^i r& f. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New Jersey 34 Gloucester 015 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^i.BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK V —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME John S. Holston, Jr. STREET & NUMBER 62 N. Broad Street CITY. TOWN STATE Woodbury VICINITY OF New Jersey (LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Gloucester County Clerk's Office STREET & NUMBER Broad and Delaware Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Woodbury New Jersey REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Building Survey N.J. 46 DATE 1936 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED ^-UNALTERED •^ORIGINAL SITE .GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE- -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bodo Otto House is a 5 bay square plan, 2 and 1/2 story stone house, which is entered in the center bay.