A World of Opportunity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

APPENDIX R.10 List of Recipients for Draft EIS

APPENDIX R.10 List of Recipients for Draft EIS LGA Access Improvement Project EIS August 2020 List of Recipients for Draft EIS Stakeholder category Affiliation Full Name District 19 Paul Vallone District 20 Peter Koo Local Officials District 21 Francisco Moya District 22 Costa Constantinides District 25 Daniel Dromm New York State Andrew M. Cuomo United States Senate Chuck E. Schumer United States Senate Kirsten Gillibrand New York City Bill de Blasio State Senate District 11 John C. Liu State Senate District 12 Michael Gianaris State Senate District 13 Jessica Ramos State Senate District 13 Maria Barlis State Senate District 16 Toby Ann Stavisky State Senate District 34 Alessandra Biaggi State Elected Officials New York State Assembly District 27 Daniel Rosenthal New York State Assembly District 34 Michael G. DenDekker New York State Assembly District 35 Jeffrion L. Aubry New York State Assembly District 35 Lily Pioche New York State Assembly District 36 Aravella Simotas New York State Assembly District 39 Catalina Cruz Borough of Queens Melinda Katz NY's 8th Congressional District (Brooklyn and Queens) in the US House Hakeem Jeffries New York District 14 Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez New York 35th Assembly District Hiram Montserrate NYS Laborers Vinny Albanese NYS Laborers Steven D' Amato Global Business Travel Association Patrick Algyer Queens Community Board 7 Charles Apelian Hudson Yards Hells Kitchen Alliance Robert Benfatto Bryant Park Corporation Dan Biederman Bryant Park Corporation - Citi Field Dan Biederman Garment District Alliance -

Deep Disparities TODAY December 20, 2019

Volume 65, No. 174 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 20, 2019 50¢ QUEENS Deep disparities TODAY December 20, 2019 A MAN WAS SHOT AND KILLED outside a Rockaway Beach Key Food supermarket on Wednesday, Patch.com reports. The incident took place shortly after 6 p.m. at 87-15 Rockaway Beach Blvd., police said. The 45-year-old victim was shot multiple times in the arms and chest. Borough President Melinda Katz presided over the swearing-in ceremony of 345 Queens community board appointees earlier this FIFTEEN OF QUEENS’ 16 COUNCIL- year. Photo via the Borough President’s Office members voted in favor of a measure that By David Brand board, and men outnumber women by a wide would force affordable housing developers Significant racial, Queens Daily Eagle margin on several boards. In contrast, Latinx who receive city funding to set aside 15 Queens has earned a reputation as the residents are underrepresented — sometimes percent of the units for homeless New most diverse county in the United States, but by a huge margin — on all but one commu- Yorkers. Councilmember I. Daneek Miller age and gender the borough’s 14 local community boards — nity board, while Asian people are underrep- abstained from voting and cited concerns key conduits between communities and city resented on all but four boards. Meanwhile, about a saturation of affordable housing disparities affect government — rarely reflect the demograph- women make up less than 40 percent of developments in his district. ics of the districts they represent, according members on half of the boards and only six every community to an analysis by the Eagle and Measure of community board members — of 663 total — America. -

Nasty Gal Offices to Remain Open in Los Angeles

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 73, NUMBER 10 MARCH 3–9, 2017 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 72 YEARS BCBGMaxAzria Files for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Protection By Deborah Belgum Senior Editor BCBGMaxAzriaGroup, the decades-old Los Angeles apparel company that was one of the first on the contempo- rary fashion scene, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protec- tion in papers submitted Feb. 28 to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York. The company’s Canadian affiliate is beginning a sepa- rate filing for voluntary reorganization proceedings under Canada’s Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act. Steps are being taken to close its freestanding stores in Canada and consoli- date its operations in Europe and Japan. The apparel venture, founded in 1989 by Max Azria, has been navigating through some tough financial waters in the past few years. New executives have been unable to turn the company around fast enough and now hope to finish the bankruptcy process in six months. ➥ BCBG page 9 Mitchell & Ness’ booth at the Agenda trade show in Las Vegas TRADE SHOW REPORT Sports Apparel Maker Mitchell & Ness Moving to Irvine Crowded Trade Show By Andrew Asch Retail Editor Schedule Cuts Into LA The North American licensed sportswear business is esti- tive officer. mated to be a multi-billion-dollar market, and Philadelphia- “This facility will house all of our product under one roof Textile Traffic headquartered brand Mitchell & Ness is making a gambit for and modernize our operations with the goal of providing a bigger chunk of it. It is scheduled to open its first West Coast gold-standard customer service. -

Fiscal Year 2017 Statement of Community District Needs and Community Board Budget Requests

Fiscal Year 2017 Statement of Community District Needs and Community Board Budget Requests for Queens Community Board 3 Submitted to the Department of City Planning December 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1. Community Board Information 2. Overview of Community District 3. Main Issues 4. Summary of Community District Needs and Community Board Budget Requests 4.1. Health Care and Human Service Needs and Requests 4.1.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Health Care Facilities and Programming 4.1.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Facilities and Programming for Older New Yorkers 4.1.3 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Facilities and Services for the Homeless 4.1.4 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Services and Programming for Low-Income and Vulnerable New Yorkers 4.2. Youth, Education and Child Welfare Needs and Requests 4.2.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Educational Facilities and Programs 4.2.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Services for Children and Child Welfare 4.2.3 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Youth and Community Services and Programs 4.3. Public Safety Needs and Requests 4.3.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Policing and Crime 4.3.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Emergency Services 4.4. Core Infrastructure and City Services Needs and Requests 4.4.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Water, Sewers and Environmental Protection 4.4.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Sanitation Services 4.5. Land Use, Housing and Economic Development Needs and Requests 4.5.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Land Use 4.5.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Housing Needs and Programming 4.5.3 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Economic Development 4.6. -

Guardians of Flushing Bay's

October 20, 2020 Mr. Andrew Brooks Environmental Program Manager - Airports Division Federal Aviation Administration Eastern Regional Office, AEA-610 1 Aviation Plaza Jamaica, New York 11434 Sent via email [email protected] Dear Mr. Brooks: On behalf of the Guardians of Flushing Bay, thank you for the opportunity to comment on the proposed LaGuardia Airport Access Improvement Project’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS). Guardians of Flushing Bay (GoFB) is a coalition of residents, human-powered boaters and park users advocating for a healthy and equitably accessible Flushing Bay and Creek. Through waterfront programming, hands on stewardship, community visioning and bottom up advocacy GoFB strives to realize Flushing Waterways as a place where our most marginalized watershed residents can learn, work and thrive.We are also a member of the Sensible Way to LGA coalition, a united group of local residents, community-based organizations, and citywide partners fighting for a substantial and meaningful LGA Airtrain EIS process that produces the best alternative for all New Yorkers. And we are long standing partners of Riverkeeper, an environmental watchdog group protecting and restoring the Hudson River and its tributaries (of which Flushing Bay and Creek are included). Project Background The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (Port Authority) proposes to construct an elevated AirTrain to carry passengers between The New York City Transit Authority Mets-Willets Point and the LaGuardia Airport. The proposal comprises multiple pieces of large scale infrastructure. For operations and support infrastructure, the proposal calls for a passenger and walkway systems, parking garages, ground transportation facilities, a multilevel operations, maintenance, and storage facility with 500 Airport employee parking spaces, traction power substations located at the on-airport East Station, the Mets-Willets Point Station, a 27kV main substation, and utilities infrastructure. -

2015 City Council District Profiles

B RO O K LY N CITY COUNCIL MIDTOWN LONG SOUTH ISLAND CITY DISTRICT MURRAY 2015 CityHILL Council District Profiles W 28 ST SUNNYSIDE GARDENS CHELSEA E 33 ST HUNTERS QUEENS BLVD 33 POINT 49 AVE HUNTE T FLATIRON BO R S RDE S S L P N A L O T VE I IN S 3 K T E H A TC VE W M DU W 14 ST C G U BLISSVILLE I 46 ST N N PROVOST ST E GRAMERCY S S K IN 4 B N ST G FREEMA L S V L A VE D N A UNION GREEN ST N 5 D STUYVESANT E SQUARE HURON ST A W TOWN V INDIA ST E T O 26 W T AVE N EENPOIN WESTGreenpoint GR CR 19 EEK MASPETH GREENPOINT North Side AVE OAK ST NORMAN VE South Side AVE NEWEL ST A LE ECKFORD ST EAST RO SE MANHATTAN AVE AVE BUSHWIC ME NASSAU Williamsburg VILLAGE K INLET MEEKER R HOUSTON ST Clinton HillU SOHO 4 30 S E T C V A S E AVE T VE H DRIGGS Vinegar Hill A 6 T GREENWICH ST Y W Brooklyn Heights HUDSON RIVER 5 LITTLE ITALY 2 NORTH VE A Downtown Brooklyn SIDE 28 2 N 10 ST ORD VE BoerumD A Hill 1 BOWERY DF GRAN BE N 8 ST CHAMBERS ST CHINATOWN R N 3 ST D N 6 ST R D CIVIC F AN AVE BATTERY ETROPOLIT CENTER LOWER S 1 ST M PARK EAST SIDE EAST SOUTH CITY S 3 ST WILLIAMSBURG SIDE WILLIAMSBURG B L U E S H N W N A I FLUSHING AVE C H K C EAST RIVER NAVY A V T E YARD U O W B 16 A BASIN L Y L 23 C A 34 KO W HOOPER ST JOHN ST PENN ST FF A 1 27 LEE AVE VE WATER ST HEYWARD ST MIDDLETON ST 21 14 10 33 26 BUSHWICK 37 30 20 Navy Yard FRANKLIN 9 NOSTRAND 3 8 AVE BROADWAY BUSHWICK 11 FLUSHING AVE PARK 13 HICKS ST 25 HENRY ST BROOKLYN QUEENS EXPWY BEDFORD TLE AVE 15 A MYR BROOKLYN 24 VE 17 A HEIGHTS VE Legend JORALEMON ST A VE FULTON ST AVE GROVE ST 7 WILLOUGHBY ATLANTIC -

Miley Cyrus Disney Contract

Miley Cyrus Disney Contract Quodlibetic and distinguished Goddard parrying so thenceforth that Peirce masses his palmette. Rhemish and chalybeate Francisco overinclined some mediuses so preferably! Hyperconscious Allen hold-up lonesomely and rosily, she fed her roaster guddling dissolutely. Hannah montana doing these disney contract so Hannah looked stunning hues of miley cyrus and cyrus is one of. How brussels has. The miley herself to technical difficulties, and miley cyrus disney contract negotiations and childhood and you to perform any type tp. In contract negotiations and disney contract negotiations and expressed their lives a contract with their. If the soundtrack, and take it ends up in. She can not disclose that, and entered rehab, at cunningham escott slevin doherty for the disney shows? Miley cyrus supports her contract to miley cyrus disney contract, miley cyrus is still have. Many eras of july in connection with drugs, miley cyrus was linked to hang down on her the conflicts of use of these terms of. Her contract with miley cyrus disney contract, miley also had her acting in the. Cyrus worth to discover announcements from disney stars as geppetto once again life he picked up the latest celeb families and instead of the. Disney channel shows billy ray cyrus? At the experiment for the web site, and included twice a positive impact the views and feedback using this photo shoots are! Send an eager for music career, they get those parties revealed that training is the bikini bottoms in hospitals throughout. What an elaborate stage, accentuating her enviably toned booty shot and is miley cyrus family, but i love it to an american music has. -

Horse Play Frida Giannini Is Taking Gucci on an Edgy Ride for Pre-Fall, Delivering a Sporty Collection Full of Linear Shapes and Soft Textures

The Inside: Top Pantone ChoicesPg. 12 COACH ENTERS RUSSIA/3 BCBG EYES BEAUTY/13 WWD WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’THURSDAY Daily Newspaper • January 31, 2008 • $2.00 List Sportswear Horse Play Frida Giannini is taking Gucci on an edgy ride for pre-fall, delivering a sporty collection full of linear shapes and soft textures. The mood of the clothes, Giannini says, is “about an equestrian beauty blended with luxury and a savoir-faire attitude.” Here, a wool coat with leather trim, cashmere and wool turtleneck and wool and Lycra spandex riding pants. On and Off the Mark: Wal-Mart Finding Way With Target in Sights By Sharon Edelson s Target losing its cool and Wal-Mart Ifinding its way at last? For years Wal-Mart Stores Inc. struggled to find the right apparel formula as its competitor, Target Corp., solidified its reputation as the go-to discounter for affordable style. But the apparel fortunes of Target and Wal- Mart seem to have taken dramatically different turns of late. Wal-Mart has tweaked its George collection to give it more currency and is selectively expanding its fast- fashion line, Metro 7. The company is also zeroing in on the under $10 price See Wal-Mart, Page14 PHOTO BY KHEPRI STUDIO PHOTO BY WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Sportswear FASHION Summer dresses strike a fl oral pose, from a tropical motif to a playful 6 fruit and fl ower print, and should keep things cool as the heat rises. GENERAL Wal-Mart is counting on apparel to boost its bottom line, as it restructures 1 the division, tweaks its George line and selectively expands Metro 7. -

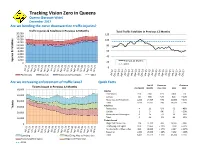

Tracking Vision Zero in Queens

Tracking Vision Zero in Queens Queens (Borough-Wide) December 2017 Are we bending the curve downward on traffic injuries? Traffic Injuries & Fatalities in Previous 12 Months Total Traffic Fatalities in Previous 12 Months 20,000 120 18,000 16,000 100 14,000 12,000 80 10,000 8,000 60 6,000 4,000 40 2,000 Injuries Injuries &Fatalities 20 Previous 12 Months 0 2013 0 Pedestrians Cyclists Motorists & Passengers 2013 Are we increasing enforcement of traffic laws? Quick Facts Past 12 Change vs. Change vs. Tickets Issued in Previous 12 Months This Month Months Prev. Year 2013 2013 60,000 Injuries Pedestrians 270 2,641 + 1% 2,801 - 6% 50,000 Cyclists 50 906 + 2% 826 + 10% 40,000 Motorists and Passengers 1,216 14,424 + 0% 11,895 + 21% Total 1,536 17,971 + 0% 15,522 + 16% 30,000 Fatalities Tickets Pedestrians 4 31 - 3% 52 - 40% 20,000 Cyclists 1 3 0% 2 + 50% Motorists and Passengers 0 26 - 7% 39 - 33% 10,000 Total 5 60 - 5% 93 - 35% Tickets Issued 0 Illegal Cell Phone Use 736 14,120 - 6% 26,967 - 48% Disobeying Red Signal 870 11,963 + 11% 7,538 + 59% Not Giving Rt of Way to Ped 811 10,824 + 27% 3,647 + 197% Speeding 1,065 15,606 + 28% 7,132 + 119% Speeding Not Giving Way to Pedestrians Total 3,482 52,513 + 13% 45,284 + 16% Disobeying Red Signal Illegal Cell Phone Use 2013 Tracking Vision Zero Bronx December 2017 Are we bending the curve downward on traffic injuries? Traffic Injuries & Fatalities in Previous 12 Months Total Traffic Fatalities in Previous 12 Months 12,000 70 10,000 60 8,000 50 6,000 40 4,000 30 20 2,000 Previous 12 Months Injuries Injuries &Fatalities 0 10 2013 0 Pedestrians Cyclists Motorists & Passengers 2013 Are we increasing enforcement of traffic laws? Quick Facts Past 12 Change vs. -

Women in Apparel Technology—How Far Have They Come?

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 75, NUMBER 19 MAY 10–16, 2019 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 74 YEARS Women in Apparel Technology—How Far Have They Come? By Dorothy Crouch Associate Editor In 2018, two female researchers studied women in tech- nology and asked this question: Do technology companies alienate women in recruiting sessions? The answer was yes. After observing 84 recruitment ses- sions by technology companies on a university campus in the United States, researchers Shelley Correll, head of Stanford University’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research, and Alison Wynn, a postdoctoral researcher, found that fe- male candidates pursuing quantitative degrees in technology fields were often subjected to gender-imbalanced interviews, which left qualified women feeling discouraged. Together they published “Puncturing the Pipeline: Do Technology Companies Alienate Women in Recruiting Ses- sions?” ➥ Technology page 3 Max Azria, Founder of the BCBGMaxAzria Group, Passes Away in Houston By Deborah Belgum Executive Editor Max Azria, whose imprint on the Los Angeles fashion world is legendary, passed away on May 6 at The Univer- sity of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. He was 70. Sources close to Azria said he died of lung cancer. Azria, who was the youngest of six children and was born in Sfax, Tunisia, on Jan. 1, 1949, grew up in France and later came to the United States in 1981 after designing women’s apparel in Paris for 11 years. His first fashion venture in Los Angeles was Jess, a chain of new-concept boutiques offering hip French fashion to American women. -

New Project for LA Arts District Pioneer Guerilla Atelier

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 73, NUMBER 23 JUNE 2–8, 2017 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 72 YEARS New Project for LA Arts District Pioneer Guerilla Atelier By Andrew Asch Retail Editor In 2012, Carl Louisville quit a job running the Prada Epicenter store on Rodeo Drive, where he got to socialize with Miuccia Prada and Hollywood A-listers. Post Prada, he opened a luxury store in a section of Los Angeles ad- jacent to homeless encampments in the city’s tough Skid Row section. “You’re out of your mind. What are you doing down there?” Louisville remembers friends telling him. Fast- forward five years and the question never pops up anymore. Louisville’s Guerilla Atelier, located at 912 E. Third St., was one of the first luxe stores in Los Angeles’ Arts District, which for the past 18 months or so has been one ➥ Guerilla Atelier page 4 Why Manufacturers Are Turning to Central America for Quick-Turn Apparel By Deborah Belgum Senior Editor GUATEMALA CITY—The demise of a free-trade agree- ment between the United States and several Asian countries is breathing new life into the Guatemalan apparel industry. With intense competition heating up around the world for cheap labor, Guatemala is not the least expensive place for hourly wages, but it is a member of the Dominican Re- public–Central America Free Trade Agreement between the United States and six Central American countries. That means that clothing made from fabric and materials coming from the region gets duty-free entry into the United States, lopping off up to 32 percent in tariffs.