Pakistan: Prison Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penology and Prison Administration

Penology and Prison Administration This course has been developed to enable the student to understand and critically evaluate the Pakistani penal system after developing an insight into the science of penology and the comparative penal systems. The course will introduce students to the various theories and perspectives that explain punishment and its role in societies. The main focus of the course will be on the prisons, both as a social institution and as society of captives. Students will also be introduced to models of prison management, administration and reform, and will analyze case studies from different countries that highlight specific issues. The course will survey the legal and institutional framework of prisons in Pakistan and introduce students to the scant scholarly literature that analyzes the present conditions of prisons in Pakistan. Learning Objectives Develop a basic understanding of the discipline of penology, the concept of punishment and its overall significance in the field of criminology. Provide a comparative overview of the history and development of the institution of Prison in the West. Functional aspects of the modern penitentiary with special emphasis of prison management, rehabilitation program and control technology will also be analyzed. Lastly, in the backdrop of globalization the perceivable future developmental trends in the western prison institution and their impact on globally marginalized groups and countries will be discussed. Understand the legal and structural framework of the Pakistani penal system from a comparative perspective. Understand the dynamics and determinants of the ‘Prison Society’ and its impact on the incarcerated. Apply this understanding in a critical analysis of the present conditions in the Pakistani prisons and their impact on the prisoners’ physical and mental health and re-entry into the mainstream society. -

Prisoners of the Pandemic the Right to Health and Covid-19 in Pakistan’S Detention Facilities

PRISONERS OF THE PANDEMIC THE RIGHT TO HEALTH AND COVID-19 IN PAKISTAN’S DETENTION FACILITIES Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) is a non-profit organization based in Lahore that represents the most vulnerable Pakistani prisoners facing the harshest punishments, at home and abroad. JPP investigates, litigates, educates, and advocates on their behalf. In recognition of their work, JPP was awarded with the National Human Rights Award in December 2016 by the President of Pakistan. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International and Justice Project Pakistan. Design by Ema Anis (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 33/3422/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 2. -

Death-Penalty-Pakistan

Report Mission of Investigation Slow march to the gallows Death penalty in Pakistan Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 Introduction and Background . 16 I. The legal framework . 21 II. A deeply flawed and discriminatory process, from arrest to trial to execution. 44 Conclusion and recommendations . 60 Annex: List of persons met by the delegation . 62 n° 464/2 - January 2007 Slow march to the gallows. Death penalty in Pakistan Table of contents Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 1. The absence of deterrence . 8 2. Arguments founded on human dignity and liberty. 8 3. Arguments from international human rights law . 10 Introduction and Background . 16 1. Introduction . 16 2. Overview of death penalty in Pakistan: expanding its scope, reducing the safeguards. 16 3. A widespread public support of death penalty . 19 I. The legal framework . 21 1. The international legal framework. 21 2. Crimes carrying the death penalty in Pakistan . 21 3. Facts and figures on death penalty in Pakistan. 26 3.1. Figures on executions . 26 3.2. Figures on condemned prisoners . 27 3.2.1. Punjab . 27 3.2.2. NWFP. 27 3.2.3. Balochistan . 28 3.2.4. Sindh . 29 4. The Pakistani legal system and procedure. 30 4.1. The intermingling of common law and Islamic Law . 30 4.2. A defendant's itinerary through the courts . 31 4.2.1. The trial . 31 4.2.2. Appeals . 31 4.2.3. Mercy petition . 31 4.2.4. Stays of execution . 33 4.3. The case law: gradually expanding the scope of death penalty . -

Prisoners' Right to Fair Justice, Health Care and Conjugal Meetings

Pakistan Journal of Criminology Vol. 10, Issue 4, October 2018 (42-59) Prisoners’ Right to Fair Justice, Health Care and Conjugal Meetings: An Analysis of Theory and Practice (A case study of the selected jails of Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan) Rais Gul1 Abstract Imprisoned people are deprived of their liberty, yet they are human beings entitled to well-defined human rights, recognized on international level, regional levels and enshrined in the legal statutes of nation-states. This paper is aimed at exploring the massive gap between theory and practice in terms of prisoners‟ rights to fair justice, conjugal meetings and proper health care with special focus on jails in Khyber-Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Seven jails of the province were purposively selected. Of all seven jails, 250 prisoners were randomly selected and interviewed. Other key respondents who were interviewed included six jail officials and five former prisoners. The study was based on Concurrent Triangulation (Mixed Methodology) technique. It was concluded that prisoners are denied there legally guaranteed rights, i.e., conjugal meetings, swift and fair justice and proper health care. In this study, for instance, more than 85 % inmates revealed that their jail had no proper space to ensure conjugal meetings, 51.2% disclosed that they were denied fair and swift trial, while 46.8% and 92.8% unveiled that they had no access to doctors and psychiatrists respectively. Moreover, it was found that prisoners once deprived of these rights, are less likely to play a law abiding and contributory role in the after-release life. It is, therefore, recommended that Pakistan, being a signatory to all the International covenants on prisoners‟ rights and having its own Constitution and Prison Rules which safeguard prisoners, must put all the rights of the caged people into practice, so as to enable its prisons to work as correction centers. -

Corrections in Pakistan (2017)

Sindh), with features of the indigenous model, are Pakistan, Corrections in local jury systems which take the responsibility YAN ZHANG of resolving issues in an informal approach. It is the respectable men of the area that constitute the Australian National University, Australia local jury. !ey listen to both victims and o$end- ers and make a "nal decision based on their own wisdom. !e Islamic model implements Islamic !e Islamic Republic of Pakistan (Pakistan) is a sharia. !e basic goal of Islamic law is to promote sovereign country located in South Asia. Its pop- a“crimefree”environmentinsteadofcorrecting ulation of more than 197 million (in 2013) makes and rehabilitating o$enders. Physical penalties it the sixth most populous country. In 2009, including corporal punishment are applied. !is Punjabis represented 44.15% of Pakistan’s model enjoys a long tradition in Muslim countries total population, ethnically ranking in "rst and particularly in Pakistan, though it has not place, followed by Pashtuns (15.42%), Sindhis been implemented completely. !e cosmopolitan (14.1%), Seraikis (10.53%), Muhajirs (7.57%), model (Western model) of justice based on the Balochs (3.57%), and other ethnic minorities “utilitarian” concept was introduced in British (4.66%). Pakistan is a federal parliamentary South Asia in the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- republic with four provinces (Punjab, Sindh, turies. !e Indian Penal Code (IPC) is a typical Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan), two example of cosmopolitan legal culture. It was autonomous and disputed territories, one fed- dra#ed in 1837, passed by the legislative assembly eral capital territory, and a group of federally in 1860 and implemented in 1862; it is now called administered tribal areas. -

Female Behind Bars Complete & Final.Cdr

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Country Office Pakistan FEMALES BEHIND BARS Situation and Needs Assessment in Female Prisons and Barracks Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Country Office Pakistan This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNODC COPAK would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. Disclaimer: This report has not been formally edited. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily represent the official policy of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Females Behind Bars Situation and Needs Assessment in Female Prisons and Barracks UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Table of Contents List of Tables List of Figures Acknowledgments i Vision Statement iii Executive Summary v 1. INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND 02 1.1 Prisons and HIV 02 1.2 The prison system in Pakistan 03 1.3 Women prisons in Pakistan 03 1.4 Project introduction 04 2. METHODOLOGY 08 2.1 Study design and sites 08 2.2 Study subjects and sample size 08 2.3 Data collection procedures 09 2.4 Data collection instrument 10 2.5 Training on data collection 10 2.6 Data management and analysis 10 2.7 Ethical considerations 10 3. RESULTS 14 3.1 No of interviews and non response 14 3.2 Socio-demographic characteristics 14 3.2.1 Age of the respondents 14 3.2.2 Educational status 14 3.2.3 Marital -

Mental Healthcare & Criminal Justice in Pakistan

M E MENTAL HEALTHCARE & N T CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN PAKISTAN A L H E A L T H April 2019 C A R E & C R A DIALOGUE REPORT I M I This report is based on the proceedings of a consultative dialogue N A convened in Islamabad by the National Academy for Prison Administrators L with support from the International Committee of Red Cross, and in J U collaboration with Justice Project Pakistan S T I C E I N P A K I S T A N A P R I L 2 0 1 9 Mental Healthcare & Criminal Justice in Pakistan Acknowledgements International Committee of Red Cross, Pakistan Justice Project Pakistan Edited by Dr Asma Humayun Consultant Psychiatrist 2 Mental Healthcare & Criminal Justice in Pakistan Contents Pages Background 4 SECTION 1 MENTAL HEALTH AND PRISONS 5 1.1 What are the goals of providing mental healthcare inside prisons? 5 1.2 What is the association between mental disorders and prisons? 5 1.3 What is forensic psychiatry? 7 SECTION 2 THE CASE: PAKISTAN 8 2.1 Prison services 8 2.2 Mental health services 11 2.3 Legal framework for protection of mentally ill defendants 12 SECTION 3 GAPS IN EXISTING SERVICES 16 3.1 Prison services 17 3.2 Mental healthcare services 19 3.3 The justice system 21 SECTION 4 WAYS FORWARD 23 4.1 Principles of interventions for mental healthcare (WHO and ICRC) 23 4.2 Best practices: Examples from the provinces 24 4.3 Recommendations 25 4.3.1 Prison services 25 4.3.2 Mental healthcare services 27 4.3.3 The justice system 29 Annexures Annex 1 Panel discussants 31 Annex 2 Links to presentations 32 Annex 3 List of prisons 33 3 Mental Healthcare & Criminal Justice in Pakistan Background The involvement of mentally disordered offenders in the criminal justice system is currently a major public health concern all over the world. -

Pakistan at Its 60Th Session

Shadow Report to the Committee against Torture on the Occasion of the Examination of the Initial Report of Pakistan at its 60th Session March 2017 By Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) World Organisation against Torture (OMCT) Society for the Protection of the Rights of the Child (SPARC) Table of Content 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................3 2. Criminalization of Torture ...................................................................................................5 a. The Prohibition of Torture in the Constitution and the Criminal Legal Frame- work ............................................................................................................................................................5 b. Draft Anti-torture Bills........................................................................................................................6 3. Lack of Investigations and Impunity for Acts of Torture and Extra-judicial Killings ........................................................................................................................................8 4. Prison Conditions and legal safeguards against ill-treatment of persons deprived of liberty ............................................................................................................... 11 a. Overcrowding ......................................................................................................................................11 b. -

Pakistan464angconjointpdm.Qxp

Report Mission of Investigation Slow march to the gallows Death penalty in Pakistan Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 Introduction and Background . 16 I. The legal framework . 21 II. A deeply flawed and discriminatory process, from arrest to trial to execution. 44 Conclusion and recommendations . 60 Annex: List of persons met by the delegation . 62 n° 464/2 - January 2007 Slow march to the gallows. Death penalty in Pakistan Table of contents Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 1. The absence of deterrence . 8 2. Arguments founded on human dignity and liberty. 8 3. Arguments from international human rights law . 10 Introduction and Background . 16 1. Introduction . 16 2. Overview of death penalty in Pakistan: expanding its scope, reducing the safeguards. 16 3. A widespread public support of death penalty . 19 I. The legal framework . 21 1. The international legal framework. 21 2. Crimes carrying the death penalty in Pakistan . 21 3. Facts and figures on death penalty in Pakistan. 26 3.1. Figures on executions . 26 3.2. Figures on condemned prisoners . 27 3.2.1. Punjab . 27 3.2.2. NWFP. 27 3.2.3. Balochistan . 28 3.2.4. Sindh . 29 4. The Pakistani legal system and procedure. 30 4.1. The intermingling of common law and Islamic Law . 30 4.2. A defendant's itinerary through the courts . 31 4.2.1. The trial . 31 4.2.2. Appeals . 31 4.2.3. Mercy petition . 31 4.2.4. Stays of execution . 33 4.3. The case law: gradually expanding the scope of death penalty . -

Protection of Pakistani Prisoners During COVID-19 Pandemic

POLICY PAPER Policy Paper Protection of Pakistani Prisoners during COVID-19 Pandemic March 25, 2020 Legal Rights Forum (LRF) is an independent, not-for-profit organization working for strengthening the rule; improving criminal justice system and providing legal aid based in Karachi, Pakistan. LRF is envision a Democratic, Just, Peaceful and Inclusive Society. LRF is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright © Legal Rights Forum (LRF) All Rights Reserved for LRF Any part of this publication can be used or cited with a clear reference to LRF, Karachi, Pakistan Legal Rights Forum: 31-C, Mezzanine Floor, Old Sunset Boulevard Phase-II, DHA, Karachi, Tell No. 021-35388695, www.lrfpk.org, [email protected] Contents - About the Author - Acknowledgement - Executive Summary 1. Government’s Duty of Care to Prisoners 2. Overcrowding in Prisons 3. Women and Children in Prisons 4. Policy Recommendations 5. Recommendations for Reducing Overcrowding in Prisons Annexure A. COVID-19: Transmission and Risk of Infection B. TRANSMISSION C. CONTAGIOUSNESS D. FATALITY RATES E. INCREASED RISK TO OLDER MALES F. COVID-19 and Prisons: A Global Response? 1. United Kingdom 2. United State of America 3. Italy 4. Iran 5. Austria 6. Scotland 7. Particular Vulnerability of Prisoners 8. Interventions to Reduce Prison Overcrowding in Pakistan About Author Malik Muhammad Tahir Iqbal is a prominent Human Rights Advocate. He has done LLM in social legislation from Karachi University. He has developed many policy papers for strengthening the rule of law, improving criminal justice system, legal aid in Pakistan. He has also developed training manuals and capacity building resources for women legal-socio-economic empowerment, women lawyers, judiciary, prosecution and police. -

Prisons in Pakistan: ‘The Institutions of Abuse’

Prisons in Pakistan: ‘The Institutions of Abuse’ Zaira Anwar f f Zaira Anwar is in her second year, of the LLB programme of the University of the Punjab, at the Pakistan College of Law. She can be reached at [email protected]. 2 PCL Student Journal of Law [Vol II:I Abstract The modern Pakistani system of imprisonment is cumbrous and poorly managed as the prisoners are not just isolated from the world but are also kept in the most inhumane circumstances. Since the system of imprisonment is one of the most important tools at the disposal of the criminal justice system in Pakistan, its proper functioning is essential to ensure the rehabilitation of convicts. It is also important to ensure that the state does not legitimise a device of abuse under the guise of retribution, which is what the prisons in Pakistan are well known for. Lack of accountability and effective oversight leaves prisoners at the behest of the prison staff which results in inmates being subjected to abusive behaviour. None of their fundamental rights are upheld and they are forced to suffer in silence to ensure their survival. While illegal practices abusing prisoners also exist, the applicable legislation will be evaluated to see what forms of abuse it allows for and how, if at all, those can be prevented. 2018] Prisons in Pakistan 3 Introduction With the rise of the state as a social order, the system of imprisonment has evolved to be one of the most important tools at its disposal. The use of prisons can be traced back to the time of Ancient Romans who emerged among the first in the world to employ them as a form of punishment, renouncing their former use of detention and torture. -

Prision Rules 2018

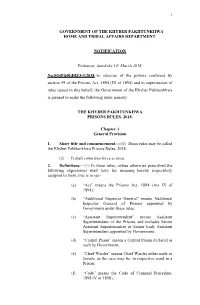

1 GOVERNMENT OF THE KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA HOME AND TRIBAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT. NOTIFICATION Peshawar, dated the 14th March 2018. No.SO(P&R)HD/3-3/2018.-In exercise of the powers conferred by section 59 of the Prisons Act, 1894 (IX of 1894) and in supersession of rules issued in this behalf, the Government of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is pleased to make the following rules, namely: THE KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PRISONS RULES, 2018. Chapter-1 General Provision 1. Short title and commencement.---(1) These rules may be called the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Prisons Rules, 2018. (2) It shall come into force at once. 2. Definitions.---(1) In these rules, unless otherwise prescribed the following expressions shall have the meaning hereby respectively assigned to them, that is to say- (a) “Act” means the Prisons Act, 1894 (Act IX of 1894); (b) “Additional Inspector General” means Additional Inspector General of Prisons appointed by Government under these rules; (c) “Assistant Superintendent” means Assistant Superintendent of the Prisons and includes Senior Assistant Superintendent or Senior Lady Assistant Superintendent appointed by Government; (d) “Central Prison” means a Central Prison declared as such by Government; (e) “Chief Warder” means Chief Warder either male or female, as the case may be, in respective ward in a Prison; (f) “Code” means the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 (V of 1898); 2 (g) “condemned prisoner” means prisoner sentenced to death and his sentence of death confirmed by the Supreme Court of Pakistan; (h) “Court” means Supreme Court, High Court,