M. A. II English P.G1 E4 Mod & Post Mod Br Lit Title.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Dancing at Lughnasa

1 Dancing at Lughnasa ACT ONE When the play opens MICHAEL is standing downstage left in a pool of light. The rest of the stage is in darkness. Immediately MICHAEL begins speaking slowly bring up the lights on the rest of the stage. Around the stage and at a distance from MICHAEL the other characters stand motionless in formal tableau. MAGGIE is at the kitchen window (right). CHRIS is at the front door. KATE at extreme stage right. ROSE and GERRY sit on the garden seat. JACK stands beside ROSE. AGNES is upstage left. They hold these positions while MICHAEL talks to the audience. MICHAEL. When I cast my mind back to that summer of 1936 different kinds of memories offer themselves to me. We got our first wireless set that summer – well, a sort of set; and it obsessed us. And because it arrived as August was about too begin, my Aunt Maggie – She was the joker of the family – she suggested we give it a name. She wanted to call it Lugh* after the old Celtic God of the Harvest. Because in the old days August the First was La Lughnasa, the feast day of the pagan god, Lugh; and the days and weeks of harvesting that followed were called the Festival of Lughnasa. But Aunt Kate – she was a national schoolteacher and a very proper woman --she said it would be sinful to christen an inanimate object with any kind of name, not to talk of a pagan god. So we just called it Marconi because that was the name emblazoned on the set. -

Dancing at Lughnasa School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Theatre and Dance Programs Theatre and Dance Fall 2013 Dancing At Lughnasa School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/sotdp Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "Dancing At Lughnasa" (2013). School of Theatre and Dance Programs. 46. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/sotdp/46 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre and Dance at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theatre and Dance Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. steve-o from MTV's Jackass October 5th Donnie Baker & Chick McGee from The Bob & Tom Show October 11th - 12th ,-----._-=,--::::a----, Ryan Stout from Chelsea Lately October 18th - 19th AI Jackson from Comedy Central October 24th - 26th Adam Ray from the hit movie "The Heat" November 14th - 16th • • f - I Drew lastings \ ~ ,, from The Bob and Tom Show ':. i ' November 22nd - 23rd • - ~ Jamie Kennedy from Malibu's Most Wanted December 5th - 7th 108 E Market Street Bloomington, IL I Phone: 309-287-7698 www.laughbloomington.com ONE E SCHOOL OF illlfi~~ ~ . Jllu,ouSrnrc u,,n••rnty AN if?\\Q\111~~ Center for the Performing Arts - Illinois State University November 1-2 & 5-9, 7:30 p.m. Matinee: November 3, 2:00 p.m. Dancing At Lughnasa by Brian Friel Director .............................................................................................................. -

Past Productions

Past Productions 2017-18 2012-2013 2008-2009 A Doll’s House Born Yesterday The History Boys Robert Frost: This Verse Sleuth Deathtrap Business Peter Pan Les Misérables Disney’s The Little The Importance of Being The Year of Magical Mermaid Earnest Thinking Only Yesterday Race Laughter on the 23rd Disgraced No Sex Please, We're Floor Noises Off British The Glass Menagerie Nunsense Take Two 2016-17 Macbeth 2011-2012 2007-2008 A Christmas Carol Romeo and Juliet How the Other Half Trick or Treat Boeing-Boeing Loves Red Hot Lovers Annie Doubt Grounded Les Liaisons Beauty & the Beast Mamma Mia! Dangereuses The Price M. Butterfly Driving Miss Daisy 2015-16 Red The Elephant Man Our Town Chicago The Full Monty Mary Poppins Mad Love 2010-2011 2006-2007 Hound of the Amadeus Moon Over Buffalo Baskervilles The 39 Steps I Am My Own Wife The Mountaintop The Wizard of Oz Cats Living Together The Search for Signs of Dancing At Lughnasa Intelligent Life in the The Crucible 2014-15 Universe A Chorus Line A Christmas Carol The Real Thing Mid-Life! The Crisis Blithe Spirit The Rainmaker Musical Clybourne Park Evita Into the Woods 2005-2006 Orwell In America 2009-2010 Lend Me A Tenor Songs for a New World Hamlet A Number Parallel Lives Guys And Dolls 2013-14 The 25th Annual I Love You, You're Twelve Angry Men Putnam County Perfect, Now Change God of Carnage Spelling Bee The Lion in Winter White Christmas I Hate Hamlet Of Mice and Men Fox on the Fairway Damascus Cabaret Good People A Walk in the Woods Spitfire Grill Greater Tuna Past Productions 2004-2005 2000-2001 -

New Articulations of Irishness and Otherness’1 on the Contemporary Irish Stage

9780719075636_4_006.qxd 16/2/09 9:25 AM Page 98 6 ‘New articulations of Irishness and otherness’1 on the contemporary Irish stage Martine Pelletier Though the choice of 1990 as a watershed year demarcating ‘old’ Ireland from ‘new’, modern, Ireland may be a convenient simplification that ignores or plays down a slow, complex, ongoing process, it is nonethe- less true to say that in recent years Ireland has undergone something of a revolution. Economic success, the so-called ‘Celtic Tiger’ phe- nomenon, and its attendant socio-political consequences, has given the country a new confidence whilst challenging or eroding the old markers of Irish identity. The election of Mary Robinson as the first woman President of the Republic came to symbolise that rapid evolution in the cultural, social, political and economic spheres as Ireland went on to become arguably one of the most globalised nations in the world. As sociologist Gerard Delanty puts it, within a few years, ‘state formation has been diluted by Europeanization, diasporic emigration has been reversed with significant immigration and Catholicism has lost its capacity to define the horizons of the society’.2 The undeniable exhil- aration felt by many as Ireland set itself free from former constraints and limitations, waving goodbye to mass unemployment and emigra- tion, has nonetheless been counterpointed by a measure of anxiety. As the old familiar landscape, literal and symbolic, changed radically, some began to experience what Fintan O’Toole has described as ‘a process of estrangement [whereby] home has become as unfamiliar as abroad’.3 If Ireland changed, so did concepts of Irishness. -

Field Day Revisited (II): an Interview with Declan Kiberd1

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 33.2 September 2007: 203-35 Field Day Revisited (II): An Interview with Declan Kiberd1 Yu-chen Lin National Sun Yat-sen University Abstract Intended to address the colonial crisis in Northern Ireland, the Field Day Theatre Company was one of the most influential, albeit controversial, cultural forces in Ireland in the 1980’s. The central idea for the company was a touring theatre group pivoting around Brian Friel; publications, for which Seamus Deane was responsible, were also included in its agenda. As such it was greeted by advocates as a major decolonizing project harking back to the Irish Revivals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its detractors, however, saw it as a reactionary entity intent on reactivating the same tired old “Irish Question.” Other than these harsh critiques, Field Day had to deal with internal divisions, which led to Friel’s resignation in 1994 and the termination of theatre productions in 1998. Meanwhile, Seamus Deane persevered with the publication enterprise under the company imprint, and planned to revive Field Day in Dublin. The general consensus, however, is that Field Day no longer exists. In view of this discrepancy, I interviewed Seamus Deane and Declan Kiberd to track the company’s present operation and attempt to negotiate among the diverse interpretations of Field Day. In Part One of this transcription, Seamus Deane provides an insider’s view of the aspirations, operation, and dilemma of Field Day, past and present. By contrast, Declan Kiberd in Part Two reconfigures Field Day as both a regional and an international movement which anticipated the peace process beginning in the mid-1990’s, and also the general ethos of self-confidence in Ireland today. -

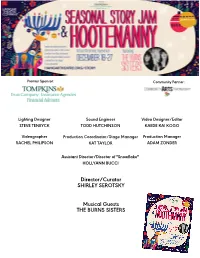

Hootenanny Insert

Premier Sponsor: Community Partner: Lighting Designer Sound Engineer Video Designer/Editor STEVE TENEYCK TODD HUTCHINSON KAEDE KAI KOGO Videographer Production Coordinator/Stage Manager Production Manager RACHEL PHILIPSON KAT TAYLOR ADAM ZONDER Assistant Director/Director of "Snowflake" HOLLYANN BUCCI Director/Curator SHIRLEY SEROTSKY Musical Guests THE BURNS SISTERS Start, pause, & rewind anytime! ORDER OF APPEARANCE 1. "Songs We Love” performed by The Burns Sisters. 2. “A Christmas Story" by Carrie Jane Thomas. Performed by Adara Alston. 3. "A Letter from Santa Claus" by Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain). Performed by Craig MacDonald with Katharyn Howd Machan, Jahmar Ortiz, and Sylvie Yntema. 4. “Golden Cradle” performed by The Burns Sisters 5. “Emmanuel” performed by The Burns Sisters. 6. "The Sermon in the Cradle" by W.E.B. DuBois. Performed by Robert Denzel Edwards. 7. "How to Spell the Name of God" by Ellen Orleans. Performed by Jennifer Herzog. 8. "Black Branches, White Moon" written and performed by Katharyn Howd Machan. 9. “Surrender” performed by The Burns Sisters. 10. "What are you Waiting For?" by Rebecca Barry. Performed by Marissa Accordino, K. Foula Dimopoulos, Kayla M. Lyon, and Gregg Miller. 11. "Food Shopping in Quarantine" by Sarah Jefferis. Performed by Sylvie Yntema. 12. "El Coquí Siempre Canta" written and performed by Sally Ramírez. 13.“Verde Luz” performed by Sally Ramirez with Special Appearance by Doug Robinson. 14. “Winter Wonderland” performed by The Burns Sisters. 15. “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” performed by The Burns Sisters. 16. “Tu Scendi Dalle Stelle” performed by The Burns Sisters. 17. "On Track" by Suzanne Snedeker. Performed by Susannah Berryman. -

William & Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM & MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

ILLUMINATING FEMALE IDENTITY THROUGH IRISH DRAMA Amy R

STRANGER IN THE ROOM: ILLUMINATING FEMALE IDENTITY THROUGH IRISH DRAMA Amy R. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of English Indiana University June 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincerest thanks are extended to my committee members for their time and feedback during this process. An added note of gratitude is extended to Dr. Jon Eller for helping to make this an educational and thoroughly enjoyable learning experience. Special appreciation goes to Dr. Mary Trotter for introducing me to many of the contemporary Irish dramatists discussed in this thesis and for her experience and expertise in this subject matter. Thanks to my fellow graduate students: Miriam Barr, Nancee Reeves and Johanna Resler for always being on my side and sharing my passion for books and words. Most importantly, thanks to Conan Doherty for always supporting me and for being the steadying voice in getting me here in spite of the hurdles. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One, A Brief History ..............................................................................................1 Chapter Two, Dancing at Lughnasa..................................................................................23 Chapter Three, Ourselves Alone ........................................................................................40 Chapter Four, The Mai.......................................................................................................56 Chapter -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Brian Friel is widely recognized as Ireland’s greatest living playwright, win- ning an international reputation through such acclaimed works as Transla- tions (1980) and Dancing at Lughnasa (1990). This collection of specially commissioned essays includes contributions from leading commentators on Friel’s work (including two fellow playwrights) and explores the entire range of his career from his 1964 breakthrough with Philadelphia, Here I Come! to his most recent success in Dublin and London with The Home Place (2005). The essays approach Friel’s plays both as literary texts and as performed drama, and provide the perfect introduction for students of both English and Theatre Studies, as well as theatregoers. The collection considers Friel’s lesser-known works alongside his more celebrated plays and provides a comprehensive crit- ical survey of his career. This is the most up-to-date study of Friel’s work to be published, and includes a chronology and further reading suggestions. anthony roche is Senior Lecturer in English and Drama at University College Dublin. He is the author of Contemporary Irish Drama: From Beckett to McGuinness (1994). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO BRIAN FRIEL -

Brian Friel's Translations: Confrontation of British Cultural Materialism with Culture Farough Fakhimi Anbaran MA (Hons) in English Literature Iran

9ROXPH,,,,VVXH9-XO\,661 Brian Friel's Translations: Confrontation of British Cultural Materialism with Culture Farough Fakhimi Anbaran MA (Hons) in English Literature Iran Abstract From the very beginning of the formation of communities people shared, at least, one common base, within that they could help them live peacefully and communicate safely and continue their lives. Culture is ubiquitous to affect human life, but cultural materialism always tends to change and adjust itself with its malevolent purposes. British cultural materialism, as one form of cultural materialism during history, affected many communities, such as those of Ireland, India, etc. to spread its territory of imperialism, but the targeted communities always confronted with effects of imperialism in different ways. Intellectuals, as an engine to these movements, have always played an important role. One of these contemporary intellectuals is Brian Friel, the Irish writer. From the very beginning of his writing career, Friel's mind was obsessed with his homeland and the occupation of it by British imperialism. He, thoughtfully, tries to reflect this issue in his plays, especially Translations which is a mirror reflecting the presence of British imperialism in Ireland, and the attempts it does to colonize Ireland from various aspects. That is why the play seems to be important from different perspectives. Using critical theory including historical-biographical, sociological, psychological, and postcolonial approaches, this study hands over and foregrounds what people should notice when they face their own and other people’s cultures in order to understand their own culture better and prevent probable problems through knowing the essence of one's own culture, one can protect it while it is being attacked by other cultures, especially by cultural materialism.