Chronic Diseases and Organ Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lung Transplantation with the OCS (Organ Care System)

Lung Transplantation with the OCSTM (Organ Care System) Lung System Bringing Breathing Lung Preservation to Transplant Patients A Guide for You and Your Family DRAFT ABOUT THIS BOOKLET This booklet was created for patients like you who have been diagnosed with end-stage lung failure and are candidates for a lung transplant. It contains information that will help you and your family learn about options available to you for a transplant. This booklet includes information on your lungs, how they function, and respiratory failure. In addition, you will learn about a new way to preserve lungs before transplantation, called breathing lung preservation. Your doctor is the best person to explain your treatment options and their risks and to help you decide which option is right for you. The booklet explains: • Breathing lung preservation with the OCS™ Lung System • How the OCS™ Lung System works • Who is eligible for the OCS™ Lung System • Lung transplant complications • How the lungs function • What is respiratory failure and the treatment options • What to expect during your treatment • Summary of clinical data for the OCS™ Lung System • Contact Information Please read this booklet carefully and share it with your family and caregivers. For your convenience, a glossary is provided in the front of this booklet. Terms in the text in bold italics are explained in the glossary. If you have questions about the OCS™ Lung System that are not answered in this booklet, please ask your physician. This booklet is intended for general information only. It is not intended to tell you everything you need to know about a lung transplant. -

Designing Biological Systems

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 4, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW Designing biological systems David A. Drubin,1 Jeffrey C. Way,2 and Pamela A. Silver1,3 1Department of Systems Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA; 2EMD Lexigen Research Center, Billerica, Massachusetts 01821, USA The design of artificial biological systems and the under- chemical systems that mimic living systems, especially standing of their natural counterparts are key objectives in regard to replication and Darwinian selection. This of the emerging discipline of synthetic biology. Toward review will primarily focus on accomplishments of the both ends, research in synthetic biology has primarily first strategy; however, readers are referred to several fine focused on the construction of simple devices, such as reviews on the generation of artificial, life-emulating transcription-based oscillators and switches. Construc- systems (Szostak et al. 2001; Benner 2003; Benner and tion of such devices should provide us with insight on Sismour 2005). the design of natural systems, indicating whether our According to the synthetic biology paradigm, a syn- understanding is complete or whether there are still gaps thetically programmed cell should be composed of many in our knowledge. Construction of simple biological sys- subsystems that operate successfully as a result of ex- tems may also lay the groundwork for the construction tensive characterization and educated design. System of more complex systems that have practical utility. To construction is the product of iterative cycles of com- realize its full potential, biological systems design bor- puter modeling, biological assembly, and testing. In this rows from the allied fields of protein design and meta- way, much from the field of systems biology can be ap- bolic engineering. -

Case Report AJNT

Arab Journal of Nephrology and Transplantation. 2011 Sep;4(3):155-8 Case Report AJNT High Ureteric Injury Following Multiorgan Recovery: Successful Kidney Transplant with Boari Flap Ureterocystostomy Reconstruction Michael Charlesworth*, Gabriele Marangoni, Niaz Ahmad Department of Transplantation, Division of Surgery, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, United Kingdom Abstract Keywords: Kidney; Transplant; Ureter; Donor efficiency Introduction: Despite increased utilization of marginal organs, there is still a marked disparity between organ The authors declared no conflict of interest supply and demand for transplantation. To maximize resources, it is imperative that procured organs are in Introduction good condition. Surgical damage at organ recovery can happen and organs are sometimes discarded as a result. Despite the extension of the donor pool with the inclusion We describe a damaged recovered kidney with high of marginal organs and the use of organs donated after ureteric transection that was successfully transplanted cardiac death, there is still a great disparity between the using a primary Boari flap ureterocystostomy. number of patients on the transplant waiting list and the number of kidney transplants performed each year. Case report: The donor kidney was procured form a It is therefore of paramount importance to maximize deceased donor and sustained damage by transection our scarce resources and avoid the discard of otherwise of the ureter just distal to the pelvi-ureteric junction at functional kidneys due to iatrogenic injuries at the time organ recovery. The recipient had been on the transplant of multi-organ recovery. Essentially, three types of organ waiting list for eight years and not accepting this kidney damage can potentially occur: vascular, parenchymal would have seriously jeopardized her chance of future and ureteric. -

Pelvic Anatomyanatomy

PelvicPelvic AnatomyAnatomy RobertRobert E.E. Gutman,Gutman, MDMD ObjectivesObjectives UnderstandUnderstand pelvicpelvic anatomyanatomy Organs and structures of the female pelvis Vascular Supply Neurologic supply Pelvic and retroperitoneal contents and spaces Bony structures Connective tissue (fascia, ligaments) Pelvic floor and abdominal musculature DescribeDescribe functionalfunctional anatomyanatomy andand relevantrelevant pathophysiologypathophysiology Pelvic support Urinary continence Fecal continence AbdominalAbdominal WallWall RectusRectus FasciaFascia LayersLayers WhatWhat areare thethe layerslayers ofof thethe rectusrectus fasciafascia AboveAbove thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? BelowBelow thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? MedianMedial umbilicalumbilical fold Lateralligaments umbilical & folds folds BonyBony AnatomyAnatomy andand LigamentsLigaments BonyBony PelvisPelvis TheThe bonybony pelvispelvis isis comprisedcomprised ofof 22 innominateinnominate bones,bones, thethe sacrum,sacrum, andand thethe coccyx.coccyx. WhatWhat 33 piecespieces fusefuse toto makemake thethe InnominateInnominate bone?bone? PubisPubis IschiumIschium IliumIlium ClinicalClinical PelvimetryPelvimetry WhichWhich measurementsmeasurements thatthat cancan bebe mademade onon exam?exam? InletInlet DiagonalDiagonal ConjugateConjugate MidplaneMidplane InterspinousInterspinous diameterdiameter OutletOutlet TransverseTransverse diameterdiameter ((intertuberousintertuberous)) andand APAP diameterdiameter ((symphysissymphysis toto coccyx)coccyx) -

Science-5-Nov-16-20 Circulatory-System.Pdf

Grade 5 Science Week of November 16 – November 20 Circulatory System Most of the cells inside of your body do not move. If a cell is hungry or needs to get rid of waste, it can’t simply move itself to the part of your body where it needs to go. Instead, your body must bring the food to your cells and take the waste away from them. By using billions of tiny tubes the circulatory system transports substances around our bodies. It delivers essential nutrients to every cell, and it transports waste products to waste-disposal sites—the lungs, the skin, and the kidneys. The circulatory system is an organ system that includes the heart, the blood vessels, and the blood itself. It has three functions: 1. to transport materials (i.e., nutrients and oxygen) and cells from one place to another 2. to defend the body against invasion by harmful organisms by taking white blood cells to an area of injury or infection 3. to maintain a constant body temperature Introduction Your body has a network of blood vessels—hollow tubes—that move blood and nutrients. A pumping organ—the heart—pushes blood through this network of vessels. Watch this video to start looking at this incredible system: https://youtu.be/tF9-jLZNM10 Complete the following. 1) Fill in the blanks: 1. Most of the cells inside of your body ________________ . If a cell is _____________ or needs to get rid of ______________, it can’t simply move itself to the part of your body where it needs to go. -

Skin Is Not the Largest Organ

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE providedRD by Elsevier Sontheimer - Publisher Connector Skin is Not the Largest Organ 3 content. CHS, JNB, and MAS were involved in Paris, France; Division of Genetics and susceptibility to psoriasis vulgaris. J Invest study supervision. Molecular Medicine, St John’s Institute of Dermatol 134:271–3 Dermatology, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK; Martin MA, Klein TE, Dong BJ et al. (2012) Clinical 1,8 4 Alexander A. Navarini , Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation pharmacogenetics implementation consortium Trust, Skin Therapy Research Unit, St John’s Laurence Valeyrie-Allanore2,8, guidelines for HLA-B genotype and abacavir 1 Institute of Dermatology, St Thomas’ Hospital, dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther 91:734–8 Niovi Setta-Kaffetzi , London, UK; 5King’s College Hospital, London, Jonathan N. Barker1,3,4, UK; 6University Medical Center Freiburg, Navarini AA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Setta-Kaffetzi N et al. (2013) Rare variations in IL36RN in 1 5 Institute of Medical Biometry and Medical Francesca Capon , Daniel Creamer , severe adverse drug reactions manifesting as 2 6 Informatics, Freiburg, Germany and Jean-Claude Roujeau , Peggy Sekula , 7 acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. 1 Department of Dermatology, J Invest Dermatol 133:1904–7 Michael A. Simpson , Dokumentationszentrum Schwerer 1 Richard C. Trembath , Hautreaktionen (dZh), Universita¨ts-Hautklinik, Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM et al. (2013) Maja Mockenhaupt7,8 and Freiburg, Germany Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated 1,3,4,8 8 Catherine H. Smith These authors contributed equally to this work. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

The NEURONS and NEURAL SYSTEM: a 21St CENTURY PARADIGM

The NEURONS and NEURAL SYSTEM: a 21st CENTURY PARADIGM This material is excerpted from the full β-version of the text. The final printed version will be more concise due to further editing and economical constraints. A Table of Contents and an index are located at the end of this paper. A few citations have yet to be defined and are indicated by “xxx.” James T. Fulton Neural Concepts [email protected] July 19, 2015 Copyright 2011 James T. Fulton 2 Neurons & the Nervous System 4 The Architectures of Neural Systems1 [xxx review cogn computation paper and incorporate into this chapter ] [xxx expand section 4.4.4 as a key area of importance ] [xxx Text and semantics needs a lot of work ] Don’t believe everything you think. Anonymous bumper sticker You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool Richard Feynman I am never content until I have constructed a model of what I am studying. If I succeed in making one, I understand; otherwise, I do not. William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) It is the models that tell us whether we understand a process and where the uncertainties remain. Bridgeman, 2000 4.1 Background [xxx chapter is a hodge-podge at this time 29 Aug 11 ] The animal kingdom shares a common neurological architecture that is ramified in a specific species in accordance with its station in the phylogenic tree and the ecological domain. This ramification includes not only replication of existing features but further augmentation of the system using new and/or modified features. -

The Device Approach to Emergent Properties

arXiv:1801.05452, Version 3 Asking Biological Questions of Physical Systems: the Device Approach to Emergent Properties Bob Eisenberg Department of Applied Mathematics Illinois Institute of Technology USA Department of Physiology and Biophysics Rush University USA [email protected] January 17, 2018 9/23/2021 9:14 AM Abstract Life occurs in concentrated ‘Ringer Solutions’ derived from seawater that Lesser Blum studied for most of his life. As we worked together, Lesser and I realized that the questions asked of those solutions were quite different in biology from those in the physical chemistry he knew. Biology is inherited. Information is passed by handfuls of atoms in the genetic code. A few atoms in the proteins built from the code change macroscopic function. Indeed, a few atoms often control biological function in the same sense that a gas pedal controls the speed of a car. Biological questions then are most productive when they are asked in the context of evolution. What function does a system perform? How is the system built to perform that function? What forces are used to perform that function? How are the modules that perform functions connected to make the machinery of life. Physiologists have shown that much of life is a nested hierarchy of devices, one on top of another, linking atomic ions in concentrated solutions to current flow through proteins, current flow to voltage signals, voltage signals to changes in current flow, all connected to make a regenerative system that allows electrical action potentials to move meters, under the control of a few atoms. -

Human Anatomy and Physiology

LECTURE NOTES For Nursing Students Human Anatomy and Physiology Nega Assefa Alemaya University Yosief Tsige Jimma University In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education 2003 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2003 by Nega Assefa and Yosief Tsige All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. Human Anatomy and Physiology Preface There is a shortage in Ethiopia of teaching / learning material in the area of anatomy and physicalogy for nurses. The Carter Center EPHTI appreciating the problem and promoted the development of this lecture note that could help both the teachers and students. -

Systems Biology and Its Relevance to Alcohol Research

Commentary: Systems Biology and Its Relevance to Alcohol Research Q. Max Guo, Ph.D., and Sam Zakhari, Ph.D. Systems biology, a new scientific discipline, aims to study the behavior of a biological organization or process in order to understand the function of a dynamic system. This commentary will put into perspective topics discussed in this issue of Alcohol Research & Health, provide insight into why alcohol-induced disorders exemplify the kinds of conditions for which a systems biological approach would be fruitful, and discuss the opportunities and challenges facing alcohol researchers. KEY WORDS: Alcohol-induced disorders; alcohol research; biomedical research; systems biology; biological systems; mathematical modeling; genomics; epigenomics; transcriptomics; metabolomics; proteomics ntil recently, most biologists’ emerging discipline that deals with, Alcohol Research & Health intend to efforts have been devoted to and takes advantage of, these enormous address. In this commentary, we will Ureducing complex biological amounts of data. Although scientists try to put the topics discussed in this systems to the properties of individual and engineers have applied the concept issue into perspective, provide views molecules. However, with the com of an integrated systemic approach for on the significance of systems biology pleted sequencing of the genomes of years, systems biology has only emerged as a new, distinct discipline to study 1 High-throughput genomics is the study of the structure humans, mice, rats, and many other and function of an organism’s complete genetic content, organisms, technological advances in complex biological systems in the past or genome, using technology that analyzes a large num the fields of high-throughput genomics1 several years. -

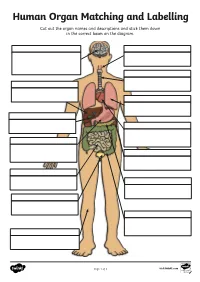

Human Organ Matching and Labelling Cut out the Organ Names and Descriptions and Stick Them Down in the Correct Boxes on the Diagram

Human Organ Matching and Labelling Cut out the organ names and descriptions and stick them down in the correct boxes on the diagram. Page 1 of 3 visit twinkl.com Maintains body temperature using Receives food from the oesophagus sweat and goosebumps. and begins to break it down with digestive juices (enzymes). Controls all of our necessary bodily functions, sends the Transports air from the nose and impulses which allow us to move mouth to the lungs. and enables you to think and learn. Pumps oxygenated blood around your body and receives de- oxygenated blood back. Filters water and salt out of your oesophagus blood and creates urine. bladder Makes bile for digestion, filters out toxins and regulates blood sugar. liver Produces enzymes necessary for large intestine digestion. gall bladder Digests food using enzymes and absorbs nutrients for the blood. kidneys Continues the digestion process, stomach absorbs as much water as possible and expels excess fibre and waste. heart Stores and concentrates bile pancreas produced by the liver. lungs Takes in oxygen, which reaches the blood via the heart. small intestine Stores urine so that we can decide trachea when we want to go to the toilet. skin Transports food and drink from the mouth to the stomach. brain Page 2 of 3 visit twinkl.com Answers brain oesophagus Controls all of our necessary bodily Transports food and drink from the functions, sends the impulses which mouth to the stomach. allow us to move and enables you to think and learn. trachea Transports air from the nose and liver mouth to the lungs.