A Case Study in Organ Allocation Policy and Administrative Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lung Transplantation with the OCS (Organ Care System)

Lung Transplantation with the OCSTM (Organ Care System) Lung System Bringing Breathing Lung Preservation to Transplant Patients A Guide for You and Your Family DRAFT ABOUT THIS BOOKLET This booklet was created for patients like you who have been diagnosed with end-stage lung failure and are candidates for a lung transplant. It contains information that will help you and your family learn about options available to you for a transplant. This booklet includes information on your lungs, how they function, and respiratory failure. In addition, you will learn about a new way to preserve lungs before transplantation, called breathing lung preservation. Your doctor is the best person to explain your treatment options and their risks and to help you decide which option is right for you. The booklet explains: • Breathing lung preservation with the OCS™ Lung System • How the OCS™ Lung System works • Who is eligible for the OCS™ Lung System • Lung transplant complications • How the lungs function • What is respiratory failure and the treatment options • What to expect during your treatment • Summary of clinical data for the OCS™ Lung System • Contact Information Please read this booklet carefully and share it with your family and caregivers. For your convenience, a glossary is provided in the front of this booklet. Terms in the text in bold italics are explained in the glossary. If you have questions about the OCS™ Lung System that are not answered in this booklet, please ask your physician. This booklet is intended for general information only. It is not intended to tell you everything you need to know about a lung transplant. -

Case Report AJNT

Arab Journal of Nephrology and Transplantation. 2011 Sep;4(3):155-8 Case Report AJNT High Ureteric Injury Following Multiorgan Recovery: Successful Kidney Transplant with Boari Flap Ureterocystostomy Reconstruction Michael Charlesworth*, Gabriele Marangoni, Niaz Ahmad Department of Transplantation, Division of Surgery, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, United Kingdom Abstract Keywords: Kidney; Transplant; Ureter; Donor efficiency Introduction: Despite increased utilization of marginal organs, there is still a marked disparity between organ The authors declared no conflict of interest supply and demand for transplantation. To maximize resources, it is imperative that procured organs are in Introduction good condition. Surgical damage at organ recovery can happen and organs are sometimes discarded as a result. Despite the extension of the donor pool with the inclusion We describe a damaged recovered kidney with high of marginal organs and the use of organs donated after ureteric transection that was successfully transplanted cardiac death, there is still a great disparity between the using a primary Boari flap ureterocystostomy. number of patients on the transplant waiting list and the number of kidney transplants performed each year. Case report: The donor kidney was procured form a It is therefore of paramount importance to maximize deceased donor and sustained damage by transection our scarce resources and avoid the discard of otherwise of the ureter just distal to the pelvi-ureteric junction at functional kidneys due to iatrogenic injuries at the time organ recovery. The recipient had been on the transplant of multi-organ recovery. Essentially, three types of organ waiting list for eight years and not accepting this kidney damage can potentially occur: vascular, parenchymal would have seriously jeopardized her chance of future and ureteric. -

Pelvic Anatomyanatomy

PelvicPelvic AnatomyAnatomy RobertRobert E.E. Gutman,Gutman, MDMD ObjectivesObjectives UnderstandUnderstand pelvicpelvic anatomyanatomy Organs and structures of the female pelvis Vascular Supply Neurologic supply Pelvic and retroperitoneal contents and spaces Bony structures Connective tissue (fascia, ligaments) Pelvic floor and abdominal musculature DescribeDescribe functionalfunctional anatomyanatomy andand relevantrelevant pathophysiologypathophysiology Pelvic support Urinary continence Fecal continence AbdominalAbdominal WallWall RectusRectus FasciaFascia LayersLayers WhatWhat areare thethe layerslayers ofof thethe rectusrectus fasciafascia AboveAbove thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? BelowBelow thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? MedianMedial umbilicalumbilical fold Lateralligaments umbilical & folds folds BonyBony AnatomyAnatomy andand LigamentsLigaments BonyBony PelvisPelvis TheThe bonybony pelvispelvis isis comprisedcomprised ofof 22 innominateinnominate bones,bones, thethe sacrum,sacrum, andand thethe coccyx.coccyx. WhatWhat 33 piecespieces fusefuse toto makemake thethe InnominateInnominate bone?bone? PubisPubis IschiumIschium IliumIlium ClinicalClinical PelvimetryPelvimetry WhichWhich measurementsmeasurements thatthat cancan bebe mademade onon exam?exam? InletInlet DiagonalDiagonal ConjugateConjugate MidplaneMidplane InterspinousInterspinous diameterdiameter OutletOutlet TransverseTransverse diameterdiameter ((intertuberousintertuberous)) andand APAP diameterdiameter ((symphysissymphysis toto coccyx)coccyx) -

Skin Is Not the Largest Organ

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE providedRD by Elsevier Sontheimer - Publisher Connector Skin is Not the Largest Organ 3 content. CHS, JNB, and MAS were involved in Paris, France; Division of Genetics and susceptibility to psoriasis vulgaris. J Invest study supervision. Molecular Medicine, St John’s Institute of Dermatol 134:271–3 Dermatology, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK; Martin MA, Klein TE, Dong BJ et al. (2012) Clinical 1,8 4 Alexander A. Navarini , Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation pharmacogenetics implementation consortium Trust, Skin Therapy Research Unit, St John’s Laurence Valeyrie-Allanore2,8, guidelines for HLA-B genotype and abacavir 1 Institute of Dermatology, St Thomas’ Hospital, dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther 91:734–8 Niovi Setta-Kaffetzi , London, UK; 5King’s College Hospital, London, Jonathan N. Barker1,3,4, UK; 6University Medical Center Freiburg, Navarini AA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Setta-Kaffetzi N et al. (2013) Rare variations in IL36RN in 1 5 Institute of Medical Biometry and Medical Francesca Capon , Daniel Creamer , severe adverse drug reactions manifesting as 2 6 Informatics, Freiburg, Germany and Jean-Claude Roujeau , Peggy Sekula , 7 acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. 1 Department of Dermatology, J Invest Dermatol 133:1904–7 Michael A. Simpson , Dokumentationszentrum Schwerer 1 Richard C. Trembath , Hautreaktionen (dZh), Universita¨ts-Hautklinik, Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM et al. (2013) Maja Mockenhaupt7,8 and Freiburg, Germany Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated 1,3,4,8 8 Catherine H. Smith These authors contributed equally to this work. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

Human Anatomy and Physiology

LECTURE NOTES For Nursing Students Human Anatomy and Physiology Nega Assefa Alemaya University Yosief Tsige Jimma University In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education 2003 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2003 by Nega Assefa and Yosief Tsige All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. Human Anatomy and Physiology Preface There is a shortage in Ethiopia of teaching / learning material in the area of anatomy and physicalogy for nurses. The Carter Center EPHTI appreciating the problem and promoted the development of this lecture note that could help both the teachers and students. -

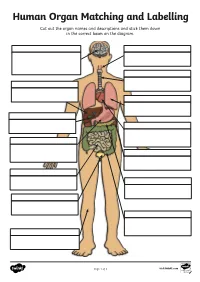

Human Organ Matching and Labelling Cut out the Organ Names and Descriptions and Stick Them Down in the Correct Boxes on the Diagram

Human Organ Matching and Labelling Cut out the organ names and descriptions and stick them down in the correct boxes on the diagram. Page 1 of 3 visit twinkl.com Maintains body temperature using Receives food from the oesophagus sweat and goosebumps. and begins to break it down with digestive juices (enzymes). Controls all of our necessary bodily functions, sends the Transports air from the nose and impulses which allow us to move mouth to the lungs. and enables you to think and learn. Pumps oxygenated blood around your body and receives de- oxygenated blood back. Filters water and salt out of your oesophagus blood and creates urine. bladder Makes bile for digestion, filters out toxins and regulates blood sugar. liver Produces enzymes necessary for large intestine digestion. gall bladder Digests food using enzymes and absorbs nutrients for the blood. kidneys Continues the digestion process, stomach absorbs as much water as possible and expels excess fibre and waste. heart Stores and concentrates bile pancreas produced by the liver. lungs Takes in oxygen, which reaches the blood via the heart. small intestine Stores urine so that we can decide trachea when we want to go to the toilet. skin Transports food and drink from the mouth to the stomach. brain Page 2 of 3 visit twinkl.com Answers brain oesophagus Controls all of our necessary bodily Transports food and drink from the functions, sends the impulses which mouth to the stomach. allow us to move and enables you to think and learn. trachea Transports air from the nose and liver mouth to the lungs. -

Biology - Student Learning Outcomes BIOL 090 Human Anatomy and 1

Biology - Student Learning Outcomes BIOL 090 Human Anatomy and 1. Explain how the major organ systems function. (ILO2, ILO5) Physiology for Health 2. Apply his/her knowledge of organ system function to solve problems based on Professionals materials and situations not covered directly in class. (ILO1, ILO2, ILO5) 3. Keep up-to-date with the materials that are covered in class. (ILO3, ILO4) BIOL 092 Microbiology For Advanced 1. understand research contributions of various scientists that have lead to the Placement of VN to RN development of modern day microbiology. (ILO4, ILO5) Nursing Students 2. understand the relationship between microbial morphology and function. (ILO2) 3. isolate pure microbial cultures using various aseptic techniques. (ILO2) 4. understand and explain microbial pathogenicty and etiology of disease. (ILO1) BIOL 100 Principles Of Biological 1. demonstrate an understanding of the steps of the scientific method. (ILO2) Science 2. communicate an understanding of the various patterns of inheritance of genetic traits. (ILO1, ILO2) 3. explain how the processes of natural selection influence evolution. (ILO1, ILO2) 4. perform lab activities properly, and correctly analyze lab data. (ILO1, ILO2) BIOL 120 General Zoology I 1. display oral communication effectiveness by doing an oral presentation of a research paper. (ILO1) 2. display the ability to show critical thinking by answering short essay type questions on exams. (ILO2) 3. display ability to understand written and illustrated information on the subject matter. (ILO4) 4. display an understanding of global impact on and by invertebrate animals. (ILO5) BIOL 122 General Zoology II 1. display oral communication effectiveness by an oral presentation of a research paper subject. -

Medical Term Lay Term(S)

MEDICAL TERM LAY TERM(S) ABDOMINAL Pertaining to body cavity below diaphragm which contains stomach, intestines, liver, and other organs ABSORB Take up fluids, take in ACIDOSIS Condition when blood contains more acid than normal ACUITY Clearness, keenness, esp. of vision - airways ACUTE New, recent, sudden ADENOPATHY Swollen lymph nodes (glands) ADJUVANT Helpful, assisting, aiding ADJUVANT Added treatment TREATMENT ANTIBIOTIC Drug that kills bacteria and other germs ANTIMICROBIAL Drug that kills bacteria and other germs ANTIRETROVIRAL Drug that inhibits certain viruses ADVERSE EFFECT Negative side effect ALLERGIC REACTION Rash, trouble breathing AMBULATE Walk, able to walk -ATION -ORY ANAPHYLAXIS Serious, potentially life threatening allergic reaction ANEMIA Decreased red blood cells; low red blood cell count ANESTHETIC A drug or agent used to decrease the feeling of pain or eliminate the feeling of pain by general putting you to sleep ANESTHETIC A drug or agent used to decrease the feeling of pain or by numbing an area of your body, local without putting you to sleep ANGINA Pain resulting from insufficient blood to the heart (ANGINA PECTORIS) ANOREXIA Condition in which person will not eat; lack of appetite ANTECUBITAL Area inside the elbow ANTIBODY Protein made in the body in response to foreign substance; attacks foreign substance and protects against infection ANTICONVULSANT Drug used to prevent seizures ANTILIPIDEMIC A drug that decreases the level of fat(s) in the blood ANTITUSSIVE A drug used to relieve coughing ARRHYTHMIA Any change from the normal heartbeat (abnormal heartbeat) ASPIRATION Fluid entering lungs ASSAY Lab test ASSESS To learn about ASTHMA A lung disease associated with tightening of the air passages ASYMPTOMATIC Without symptoms AXILLA Armpit BENIGN Not malignant, usually without serious consequences, but with some exceptions e.g. -

Human Body Systems SKELETAL SYSTEM

Human Body Systems SKELETAL SYSTEM The framework of the body, consisting of bones and other tissues, which protect and support the body and internal organs. Skeletal System Functions: 1. Protection: protects our vital organs 2. Support: Gives our bodies a shape 3. Movement: works with muscles to allow us to move. 4. Blood: Bone marrow makes blood cells. 5. Storage: Stores nutrients like calcium that makes bones hard. Skeletal System Major Components: 1. Bones- Rigid organs that form the endoskeleton of vertebrate animals 2. Cartilage-Stiff yet flexible tissue that connects different parts of the body. (ears, nose, etc) 3. Ligaments- Loose tissue that connects bone to bone 4. Joints- The place where two or more bones make contact (knees, fingers, elbows) 5. Tendon- Connects muscle to bone. Three major types of Joints: 1.Pivot Joint: Rotating joints that allow rotation around an axis. Example: Neck 2.Ball-and-Socket Joint: Most maneuverable joint that allows forward, backward, and circular movement. Example: Hip 3. Hinge Joint: Opens and closes like a door. Example: Elbow Skeletal System Interesting Facts: 1. Humans and giraffes have the same number of bones in their necks. Giraffes just have longer bones. 2. Humans have over 230 moveable and semi-moveable joints 3. The longest bone in your body is your femur. It is about ¼ of your total height. MUSCULAR SYSTEM Muscular System Functions: 1. Enables body to move 2. Homeostasis: Produces heat that helps body maintain constant temperature. 3. Helps give the body its posture and overall shape. Supports neck and head. Muscular System Major components: 1. -

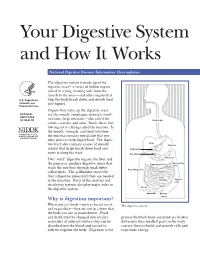

Your Digestive System and How It Works

Your Digestive System and How It Works National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse The digestive system is made up of the digestive tract—a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus—and other organs that U.S. Department help the body break down and absorb food of Health and (see figure). Human Services Organs that make up the digestive tract NATIONAL are the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small INSTITUTES OF HEALTH intestine, large intestine—also called the Esophagus colon—rectum, and anus. Inside these hol low organs is a lining called the mucosa. In the mouth, stomach, and small intestine, the mucosa contains tiny glands that pro duce juices to help digest food. The diges Liver tive tract also contains a layer of smooth Stomach muscle that helps break down food and Gallbladder move it along the tract. Duodenum Two “solid” digestive organs, the liver and Pancreas Descending the pancreas, produce digestive juices that Transverse Colon colon reach the intestine through small tubes Ascending colon called ducts. The gallbladder stores the Jejunum liver’s digestive juices until they are needed Small intestine Sigmoid in the intestine. Parts of the nervous and colon circulatory systems also play major roles in Ileum the digestive system. Cecum Appendix Rectum Why is digestion important? Anus When you eat foods—such as bread, meat, The digestive system. and vegetables—they are not in a form that the body can use as nourishment. Food and drink must be changed into smaller process by which food and drink are broken molecules of nutrients before they can be down into their smallest parts so the body absorbed into the blood and carried to can use them to build and nourish cells and cells throughout the body. -

Tissues, Organs, and Organ Systems

Tissues, Organs, and Organ Systems The cells of most animals interact at three levels of organization: tissues, organs, and organ systems Outline 1. Key concepts 2. Organization of the animal body 3. Tissues types 4. Organ systems 5. Conclusions Key Concepts: 1. The cells of most animals interact at three levels of organization: tissues, organs, and organ systems 2. Four types of tissues are seen in most animals: epithelial, connective, muscle, and nervous tissues 3. Each animal cells engages in metabolic activities Organization of the animal body 1. Cells – basic structural and functional units. 2. Tissue – a group of cells, usually similar in both structure and function. They are bound together to carry out one or more specialized tasks. 3. Organ – a body part. two or more tissue types that function together. 4. Organ systems – two or more organs that work to perform a common function. Tissue types 1. Epithelial tissue - Protective coverings of the body, linings of internal organs. cells close together act as a barrier 2. Connective tissue - structural support of body parts, energy storage, etc. cells separated by matrix tendons, ligaments, cartilage, bone, adipose tissue and blood Tissue types 3. Muscle tissue - movement of body parts and internal organs. contractible cells A. skeletal – cells very long, voluntary control. B. smooth – line internal organs, involuntary control. C. Cardiac – only in heart, involuntary. 4. Nerve tissue – regulation of body activities by receiving and sending electric signals. composed of cells called