14196-9781463915940.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0285.1.00.Pdf

the great awakening Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) the great awakening: New Modes of Life amidst Capitalist Ruins. Copy- right © 2020 by the editors and authors. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books en- dorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2020 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-953035-08-0 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-953035-09-7 (ePDF) doi: 10.21983/P3.0285.1.00 lccn: 2020945724 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Copy Editing: Lucy Barnes Book Design: Vincent W.J. -

19064 Leggglobal SAR 0805

Western Asset Legg Mason U.S. Money Market Fund Western Asset Global Funds Plc U.S. Core Bond Fund Western Asset Euro Core Bond Fund Semi-Annual Report (Unaudited) Western Asset Diversified Strategic Income Bond For the period ended August 31, 2005 Fund Western Asset Global Multi Strategy Fund Western Asset U.S. High Yield Bond Fund Western Asset Emerging Markets Bond Fund Brandywine Global Opportunities Bond Fund Legg Mason Growth Fund Legg Mason Value Fund Royce U.S. Small Cap Equity Fund Royce 100 Equity Fund Batterymarch European Equity Fund Batterymarch Pacific Equity Fund Legg Mason Global Funds Plc Semi-Annual Report August 31, 2005 Table of Contents Introduction – Legg Mason Global Funds Plc 2 Market Commentary & Fund Reviews 4 Portfolio of Investments – Western Asset U.S. Money Market Fund 9 Portfolio of Investments – Western Asset U.S. Core Bond Fund 11 Portfolio of Investments – Western Asset Euro Core Bond Fund 16 Portfolio of Investments – Western Asset Diversified Strategic Income Bond Fund 19 Portfolio of Investments – Western Asset Global Multi Strategy Fund 23 Portfolio of Investments – Western Asset U.S. High Yield Bond Fund 31 Portfolio of Investments – Western Asset Emerging Markets Bond Fund 35 Portfolio of Investments – Brandywine Global Opportunities Bond Fund 37 Portfolio of Investments – Legg Mason Growth Fund 38 Portfolio of Investments – Legg Mason Value Fund 39 Portfolio of Investments – Royce U.S. Small Cap Equity Fund 40 Portfolio of Investments – Royce 100 Equity Fund 44 Portfolio of Investments – Batterymarch European Equity Fund 46 Portfolio of Investments – Batterymarch Pacific Equity Fund 47 Statement of Assets and Liabilities – Legg Mason Global Funds Plc 50 Statement of Operations – Legg Mason Global Funds Plc 54 Statement of Changes in Net Assets Attributable to Holders of Redeemable Participating Shares – Legg Mason Global Funds Plc 56 Notes to Financial Statements – Legg Mason Global Funds Plc 62 Financial Information – Legg Mason Global Funds Plc 82 Statement of Major Portfolio Changes – Western Asset U.S. -

University of California Berkeley Department of Economics

- - _ University of California Berkeley CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL AND DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS RESEARCH Working Paper No. C93-009 Patterns in Exchange Rate Forecasts for 25 Currencies Menzie Chinn and Jeffrey Frankel January 1993 Department of Economics WITHDRAWN POU. AGRICULTURAL N OM CL. LIBRARY MAR 1 !' ben CIDER t CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL AND DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS RESEARCH The Center for International and Development Economics Research is funded by the Ford Foundation. It is a research unit of the Institute of International Studies which works closely with the Department of Economics and the Institute of Business and Economic Research. CIDER is devoted to promoting research on international economic and development issues among Berkeley CIDER faculty and students, and to stimulating collaborative interactions between them and scholars from other developed and developing countries. INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH Richard Sutch, Director The Institute of Business and Economic Research is an organized research unit of the University of California at Berkeley. It exists to promote research in business and economics by University faculty. These working papers are issued to disseminate research results to other scholars. Individual copies of this paper are available through IBER, 156 Barrows Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720. Phone (510) 642-1922, fax (510) 642-5018. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY Department of Economics Berkeley, California 94720 - ,CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL AND DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS RESEARCH Working Paper No. C93-009 Patterns in Exchange Rate Forecasts for 25 Currencies Menzie Chinn and Jeffrey Frankel January 1993 Key words: expectations, survey, forward rate, exchange rate JEL Classification: F31, 015 Abstract The properties of exchange rate forecasts are investigated, with a data set encompassing a broad cross section of currencies. -

LN.2-F Sfrkz

42>f<> t 0 -LN.2-f SfrKz TheWofld Bnk aM OM.CAL USE ONL' Public Disclosure Authorized MICROFICHE COPY bpwt No. P-5666-PE Report No. P- 5666-PE Type: (PR) SHEPHERD, / X31912 / I7 051/ LAlCO REPORTAND RECOMMNATION OF THE PR-SIDENT OF THE Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONALBANK FOR RECONSTRUCTIONAND DEVELOPMENT TO THE EXECUTIVEDIf 4- TORS ,'. ON A PROPOSEEDT1OADE POLICY REFORMLOAN IN AN AMOUNTEQUIVALENT TO US$300 MILLION TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLICOF PERU JANUARY10, 1992 Public Disclosure Authorized Thisdocnett has a resrictddbutio and may be and by recip onlyin thLeperfomance of thei:oficia s, ItsntetsmaY Mt otherw be disrelsedwithout Worl n thoriati MEN,CY EQUIVALENTS (As of December30, 1991) CurrencyUnit NuevoSol (SI.)V US$1.00 - S/.0.9S SI.1.00 = US$1.05 GOVERNMENTS FISCAL XEAR January 1 - December31 ABBREVIATIONS ALADI - Asociacid6nLatino-Ametica de Inttegract6n (Latin Ameria IntegrationAsociation) CERTEX Certiricado de Reinte TnbutWat a ta Exportacl4n(Export Tax Reimbutement Certificate) CIF Cost, Insurance and Freight D.L - DecMo Lcgslatvo (Lgisatie Decree) D.S. - Decreto Supremo (Supreme Decree) ECASA - Empresa de Comercializacidndel Arroz SA (Rice Marketing Company) ENCI - Empresa Naciontl de Comercializaa6nde Insumos(National Inputs Marketing Company) FENT - Fondo de ExportaonOs No Tradiconales (Fund for Non-Taditional Exports) F.AR - Fondo latinoeicno de Reservas (latin America Reserve Fund) FONCODES - Fondo Nacional de Compensaci6oy De ollo Soial (National Fund for Socal Compensationand Development) GATT -

La Nature Sociale De La Monnaie. Enjeux Théoriques Et Portée Institutionnelle the Social Nature of Money

Revue Interventions économiques Papers in Political Economy 59 | 2018 La nature sociale de la monnaie. Enjeux théoriques et portée institutionnelle The Social Nature of Money. Theoretical Challenges and Institutional Issues Adrien Faudot, Jonathan Massonnet et Jean-François Ponsot (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/interventionseconomiques/3613 DOI : 10.4000/interventionseconomiques.3613 ISBN : 1710-7377 ISSN : 1710-7377 Éditeur Association d’Économie Politique Référence électronique Adrien Faudot, Jonathan Massonnet et Jean-François Ponsot (dir.), Revue Interventions économiques, 59 | 2018, « La nature sociale de la monnaie. Enjeux théoriques et portée institutionnelle » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2018, consulté le 24 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ interventionseconomiques/3613 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/interventionseconomiques.3613 Les contenus de la revue Interventions économiques sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Revue Interventions économiques Papers in Political Economy 59 | 2017 La nature sociale de la monnaie. Enjeux théoriques et portée institutionnelle The Social Nature of Money. Theoretical Challenges and Institutional Issues Adrien Faudot, Jonathan Massonnet et Jean-François Ponsot (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/interventionseconomiques/3613 ISSN : 1710-7377 Éditeur Association d’Économie Politique Référence électronique Adrien Faudot, Jonathan Massonnet et Jean-François Ponsot (dir.), Revue Interventions économiques, 59 | 2017, « La nature sociale de la monnaie. Enjeux théoriques et portée institutionnelle » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 20 décembre 2017, consulté le 09 janvier 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ interventionseconomiques/3613 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 9 janvier 2018. Les contenus de la revue Interventions économiques sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. -

General Agreement on Restricted

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON RESTRICTED C/W/590 2 June 1989 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution COUNCIL June 1989 DRAFT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE TRADING SYSTEM SEPTEMBER 1988 - FEBRUARY 1989 Report by-the Secretariat TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 2 OVERVIEW OF DEVELOPMENTS 3 DEVELOPMENTS IN TRADE POLICIES AND MEASURES 7 I Soctoral Developments 7 1I Regional Developments 34 III Tariffs and Related Matters 42 IV Genteralized System of Preferences 57 V Quantitative Restrictions and Other Non-Tariff Measures 60 VI Government Aids, Subsidies, Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Actions 68 VII Export Restraint Arrangements 89 VIII Other Trade Policy Developments 93 - Coutmertrade 96 - Bilateral trade agreements 99 IX ProspeCtive Trade Policy Developments 103 X Movements in Exchange Rates 113 XI Trade-Related Developments in Other Fields 122 * * * APPENDICES I Notifications Related to Requirements Applicable to Contracting Parties Generally 126 II Notifications RequA red from Certain Contracting Parties 144 III Notifications under the MTN Agreements and Arrangements 146 IV Notifications under the HWA 150 V Export Restraint Arrangements: Voluntary Export Restraints, Orderly Marketing Arrangements, Export Forecasts, etc. 156 89-0769 C/W/590 Page 2 INTRODUCTION 1. The present report covers developments in trade policies and related matters in the period 1 September 1988-28 February 1989, and is intended to provide a basis for the review of developments in the trading system by the Council at its special meeting to be held on 21 June 1989. 2. Since 1980, the Council has held periodic special meetings to review developments in the trading system. Initially, such meetings were related exclusively to the 1979 Understanding regarding Notification, Consultation, Dispute Settlement and Surveillance (BISD 26S/210). -

Survey Data on Exchange Rate Expectations: More Currencies, More Horizons, More Tests

SURVEY DATA ON EXCHANGE RATE EXPECTATIONS: MORE CURRENCIES, MORE HORIZONS, MORE TESTS by Menzie D. Chinn Jeffrey A. Frankel University of California, Harvard University Santa Cruz (Revisions, March 14, 1999, and February 11, 2000) Forthcoming, Monetary Policy, Capital Flows and Financial Market Developments in the Era of Financial Globalisation: Essays in Honour of Max Fry, edited by Bill Allen and David Dickinson. Summary This paper works with a comprehensive set of survey data, on forecasts for 24 currencies (against the dollar), thus going beyond the traditional G-7 countries to consider smaller and less developed countries. We apply the data set to four topics. (1) We find some ability in the survey data to predict future movements in the exchange rate (and in the right direction!). As in past tests, the forecasts are nevertheless biased: variability of expected depreciation is excessive, especially at the 3-month horizon. (2) We find some evidence of a time-varying risk premium, especially at the 12-month horizon. But the coefficient on the forward discount is usually significantly greater than 1/2, implying that the risk premium is less variable than is expected depreciation. (3) We examine new data on forecasts at the five-year horizon and obtain, somewhat disappointingly, only weak evidence of regressive expectations towards purchasing power parity. (4) We have no success in an attempt to use the survey data in an equation of exchange rate determination. Acknowledgements: We thank Data Resources, Inc. for providing exchange rate data. James Hirakawa provided assistance in collecting data. We acknowledge the financial support of UCSC Academic Senate research funds. -

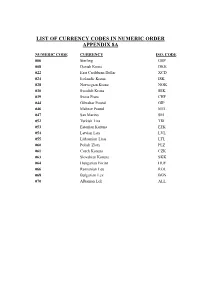

List of Currency Codes in Numeric Order Appendix 8A

LIST OF CURRENCY CODES IN NUMERIC ORDER APPENDIX 8A NUMERIC CODE CURRENCY ISO. CODE 006 Sterling GBP 008 Danish Krone DKK 022 East Caribbean Dollar XCD 024 Icelandic Krona ISK 028 Norwegian Krone NOK 030 Swedish Krona SEK 039 Swiss Franc CHF 044 Gibraltar Pound GIP 046 Maltese Pound MTL 047 San Marino SM 052 Turkish Lira TRL 053 Estonian Koruna EEK 054 Latvian Lats LVL 055 Lithuanian Litas LTL 060 Polish Zloty PLZ 061 Czech Koruna CZK 063 Slovakian Koruna SKK 064 Hungarian Forint HUF 066 Romanian Leu ROL 068 Bulgarian Lev BGN 070 Albanian Lek ALL NUMERIC CODE CURRENCY ISO. CODE 075 Russian Rouble RUR 083 Kyrgyzstan Som KGS 091 Slovenian Tolar SIT 092 Croatian Dinar HRD 094 Serbian + Monteneg. Dinar YUN 096 Macedonian MKD 204 Moroccan Dirham MAD 208 Algerian Dinar DZD 212 Tunisian Dinar TND 216 Libyan Dinar LYD 220 Egyptian Pound EGP 224 Sudanese Pound SDP 228 Mauritanian Ouguiya MRO 247 Cape Verde Escudo CVE 252 Gambian Dalasi GMD 257 Guinea-Bissau Peso GWP 260 Guinea Franc GNS 264 Sierra Leone SLL 268 Liberian Dollar LRD 276 Ghana Cedi GHC 288 Nigerian Naira NGN 310 Guinea Ekwele GQE 311 Sao Tome Dobra STD 322 Zaire ZRZ 324 Rwanda Franc RWF 328 Burundi Franc BIF 329 St. Helena Pound SHP 330 Angolan Kwanza AOK 334 Ethiopian Birr ETB 338 Djibouti Franc DJF 342 Somalia Shilling SOS 346 Kenyan Shilling KES 350 Uganda Shilling UGS 352 Tanzanian Shilling TZS NUMERIC CODE CURRENCY ISO. CODE 355 Seychelles Rupee SCR 366 Mozambique Metical MZM 370 Madagascar Franc MGF 373 Mauritius Rupee MUR 375 Comorian Franc KMF 378 Zambian Kwacha ZMK 382 Zimbabwe -

Judicial Review and Constitutional Stability: a Sociology of the U.S

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 21 Article 2 Number 1 Fall 1997 1-1-1997 Judicial Review and Constitutional Stability: A Sociology of the U.S. Model and its Collapse in Argentina Jonathan Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan Miller, Judicial Review and Constitutional Stability: A Sociology of the U.S. Model and its Collapse in Argentina, 21 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 77 (1997). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol21/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judicial Review and Constitutional Stability: A Sociology of the U.S. Model and its Collapse in Argentina By JONATHAN MILLER* I. Introduction Constitutional trends in the world today reveal a strong movement among new democracies to provide for judicial review.' The precise model may vary from that of the United States, with many countries prefer- ring to send all constitutional issues to a single court and some providing for review before a law takes effect.3 However, no one can doubt the basic trend toward review exercised by a judicial or quasi-judicial organ. Given the fractious nature of political competition, the most obvious reason for the rise of judicial review is that pluralist societies require a respected in- stitution or institutions to resolve disputes over the interpretation and ap- * Professor of Law, Southwestern University School of Law. -

Evaluation of Export Enhancement, Dollar Depreciation, and Loan Rate Reduction for Wheat (AGES 89-6)

USDA’s Economic Research Service has provided this report for historical research purposes. Current reports are available in AgEcon Search (http://ageconsearch.umn.edu) and on https://www.ers.usda.gov. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service https://www.ers.usda.gov A 93.44 AGES 89-6 ed States „cpartment of Evaluation of Export Agriculture Economic Enhancement, Dollar Research Service Depreciation, and Loan Rate Agriculture and Trade Analysis Reduction for Wheat Division Stephen L. Haley WAIT MEMORIAL BOOK DEPT. OF COLLECTION AG. AND APPLIED 1994 BUFORD ECONOMICS AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF St PAUL, MN MINNESOTA 55108 U.SA. Want Another Copy? It's Easy. Just dial 1-800-999-6779. Toll free. Ask for Evaluation of Export Enhancement, Dollar Depreciation, and Loan Rate Reduction for Wheat (AGES 89-6). The cost is $5.50 per copy. For non-U.S. addresses, add 25 percent (includes Canada). Charge your purchase to your VISA or MasterCard, or we can bill you. Or send a check or purchase order (made payable to ERS-NASS) to: ERS-NASS P.O. Box 1608 Rockville, MD 20850. We'll fill your order via 1st class mail. ................... .................. .................................. ••••••••••••• • E. H EVALUATION OF EXPORT ENHANCEMENT, DOLLAR DEPRECIATION, AND LOAN RATE REDUCTION FOR WHEAT, by Stephen L. Haley, Agriculture and Trade Analysis Division, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Staff Report No. AGES 89-6. ABSTRACT Ghis report evaluates the effect of export enhancement, dollar depreciation, and a 5-percent loan rate reduction on U.S. wheat exports for the 1986/87 crop yearL-2 Depending on one's interpretation of the European Community's motivation for its own targeted subsidy program, U.S. -

An Essay in Honor of Axel Leijonhufvud

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bordo, Michael D.; Jonung, Lars Working Paper Monetary Regimes, Inflation And Monetary Reform: An Essay in Honor of Axel Leijonhufvud Working Paper, No. 1994-07 Provided in Cooperation with: Department of Economics, Rutgers University Suggested Citation: Bordo, Michael D.; Jonung, Lars (1994) : Monetary Regimes, Inflation And Monetary Reform: An Essay in Honor of Axel Leijonhufvud, Working Paper, No. 1994-07, Rutgers University, Department of Economics, New Brunswick, NJ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/94312 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu MONETARY REGIMES, INFLATION AND MONETARY REFORM: AN ESSAY IN HONOR OF AXEL LEIJONHUFVUD Michael D. -

Financial Statements As of and for the Years Ended June 30, 2020 and 2019

Houston Police Officers’ Pension System a Component Unit of the City of Houston, Texas Financial Statements As of and for the Years Ended June 30, 2020 and 2019 Houston Police Officers’ Pension System a Component Unit of the City of Houston, Texas Financial Statements As of and for the Years Ended June 30, 2020 and 2019 Houston Police Officers' Pension System Contents Independent auditor’s report 2-3 Management’s discussion and analysis (unaudited) 4-7 Basic financial statements Statements of fiduciary net position 8 Statements of changes in fiduciary net position 9 Notes to financial statements 10-33 Required supplementary information (unaudited) Schedule of changes in the system’s net pension liability and related ratios 34 Schedule of employer contributions 35 Schedule of investment returns 36 Supplemental schedules Investment, professional and administrative expenses 37 Summary of investment and professional services 38 1 Tel: 713-960-1706 2929 Allen Parkway, 20th Floor Fax: 713-960-9549 Houston, Texas 77019-7100 www.bdo.com Independent Auditor’s Report The Board of Trustees Houston Police Officers’ Pension System Houston, Texas Report on the Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Houston Police Officers’ Pension System (the System), a component unit of the city of Houston, Texas, as of and for the years ended June 30, 2020 and 2019, and the related notes to the financial statements, which collectively comprise the System’s basic financial statements as listed in the table of contests. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.