The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There (The Blackwell

ftoc.indd viii 6/5/10 10:15:56 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/5/10 10:15:35 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Family Guy and Philosophy Kevin Decker Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Heroes and Philosophy The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by David Kyle Johnson Edited by Jason Holt Twilight and Philosophy Lost and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and Edited by Sharon Kaye J. Jeremy Wisnewski 24 and Philosophy Final Fantasy and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Michel S. Beaulieu Battlestar Galactica and Iron Man and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Jason T. Eberl Alice in Wonderland and The Offi ce and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Richard Brian Davis Batman and Philosophy True Blood and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Edited by George Dunn and Robert Arp Rebecca Housel House and Philosophy Mad Men and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Edited by Rod Carveth and Watchman and Philosophy James South Edited by Mark D. White ffirs.indd ii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY WE WANT TO GO TO THERE Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM To pages everywhere . -

ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 25 Index

1 | P a g e ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 25 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 13 June 2021 ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 14 June 2021 .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Tuesday, 15 June 2021 ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Wednesday, 16 June 2021 .................................................................................................................................. 20 Thursday, 17 June 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 26 Friday, 18 June 2021 ........................................................................................................................................... 32 Saturday, 19 June 2021 ....................................................................................................................................... 38 2 | P a g e ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 25 Sunday 13 June 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 13 June 2021 5:00am Rainbow Chicks (CC,Repeat,G) 5:05am Timmy Time (CC,Repeat,G) 5:20am -

The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 74 Issue 4 May 2021 Article 1 5-2021 The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges Nathan Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Nathan Campbell, The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges, 74 Vanderbilt Law Review 1137 (2021) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol74/iss4/1 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DOWNLOADED: Tue Aug 24 13:20:16 2021 SOURCE: Content Downloaded from HeinOnline Citations: Bluebook 21st ed. Nathan Campbell, The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges, 74 VAND. L. REV. 1137 (2021). ALWD 6th ed. Campbell, N. ., The duty to update corporate emissions pledges, 74(4) Vand. L. Rev. 1137 (2021). APA 7th ed. Campbell, N. (2021). The duty to update corporate emissions pledges. Vanderbilt Law Review, 74(4), 1137-1186. Chicago 17th ed. Nathan Campbell, "The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges," Vanderbilt Law Review 74, no. 4 (May 2021): 1137-1186 McGill Guide 9th ed. Nathan Campbell, "The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges" (2021) 74:4 Vand L Rev 1137. AGLC 4th ed. Nathan Campbell, 'The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges' (2021) 74(4) Vanderbilt Law Review 1137. MLA 8th ed. Campbell, Nathan. "The Duty to Update Corporate Emissions Pledges." Vanderbilt Law Review, vol. -

Gender and Humour II: Reinventing The

Issue 2011 35 Gender and Humour II: Reinventing the Genres of Laughter Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 Editor About Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As an English Department electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of-charge Albertus-Magnus-Platz platform for the discussion of gender-related topics in the D-50923 Köln/Cologne fields of literary and cultural production, media and the Germany arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Beate Neumeier in 2002, the quarterly issues of the journal Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 have focused on a multitude of questions from different email: [email protected] theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and Editorial Office poetry with a gender studies angle. Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA Sarah Youssef, MA Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) are those of individual authors and not necessarily endorsed by the editors of gender forum. Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 Prof. -

Tuesday ›› Women

12 • The Winchester Sun • March 9 - 15, 2012 Tambor. A wannabe serial killer Humanity fights back against Tanya Allen. An indebted grifter Fashion Star wins the lottery. (1h55) Skynet’s machine army. (2h00) launches a website that exploits 9:30 p.m. on WAVE, WLEX Tuesday ›› women. (1h30) Supermodel Elle Macpherson hosts movies 7:00 p.m. SPIKE “Rambo” 8:30 p.m. HBO “Love & Other (2008, Action) Sylvester Stal- Drugs” ››‡ (2010, Drama) 10:30 p.m. AMC “Escape From this competitive reality series in which 5:15 p.m. SHOW “All Good lone, Julie Benz. A clergyman Jake Gyllenhaal, Anne Hatha- L.A.” ›› (1996, Action) Kurt 14 unknown designers will get the Things” (2010, Mystery) Ryan persuades Rambo to rescue way. A pharmaceutical sales- Russell, Stacy Keach. Snake chance to win the opportunity to launch Gosling, Kirsten Dunst. The wife their collections in three of America’s captive missionaries in Burma. man romances a free-spirited Plissken faces foes in the ruins of a New York real estate scion (2h00) woman. (2h00) of 2013 Los Angeles. (2h30) largest retailers: Macy’s, H&M and suddenly goes missing. (1h45) Saks Fifth Avenue. At the end of each 8:00 p.m. FX “Step Brothers” 10:00 p.m. MAX “X-Men: First 11:30 p.m. TMC “Casino Jack” episode, viewers will have the chance 6:30 p.m. HBO “Men in Black” ››‡ (2008, Comedy) Will Fer- Class” ››› (2011, Action) ››‡ (2010, Docudrama) Kevin to immediately purchase the winning ››› (1997, Action) Tommy Lee rell, John C. Reilly. Two spoiled James McAvoy, Michael Fass- Spacey, Barry Pepper. -

Jared Mack Battle Ground, WA (541) 922-8278 [email protected]

1 Jared Mack Battle Ground, WA (541) 922-8278 [email protected] EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts in Acting, May 2016 Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois Final Project Documentation: Process and Performance of George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Bachelor of Arts in Theatre, 2013 Hunter College, New York, New York Certificate in Integrated Professional Actor Training, 2007 American Musical and Dramatic Academy, New York, New York Summer Intensive at the Moscow Art Theatre, 2015 In part of the completion of Master of Fine Arts, NIU UNIVERSITY TEACHING EXPERIENCE Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois Instructor Taught beginning and intermediate acting technique to multiple skill levels, including theatre majors, minors, and non-theatre majors. Curriculum based on the teachings of Stanislavski, Meisner, and Michael Chekhov. Worked with the importance of self-awareness, the art of tracking, and the incorporation of beginning environment work. While contemporary realism was at the core of instruction, students were encouraged to explore other forms of expression through one project per semester. Guided actors to work with a research binder including imagery, psychology, history, and script analysis. Theatre 214 – Introduction to Acting for the Theatre Major Spring 2015 Emphasized the necessity of an alert and active body, honest yet impassioned action, and beginning Meisner repetition work. Coached dynamic monologue instruction for the audition. Introduced text analysis with a focus on choosing objectives that help drive the action of the story. Improvisation exercises were often used to help identify beats, or new moments of action. Promoted the use of the body as a tool for effective storytelling through physical etudes and vignettes. -

Shmanners 258: Earth Day Published on April 23Rd, 2021 Listen Here on Themcelroy.Family

Shmanners 258: Earth Day Published on April 23rd, 2021 Listen here on TheMcElroy.family Travis: Why are recycling bins so optimistic? Teresa: I don't know, why? Travis: 'Cause they're full of cans! Teresa: Ahh. It's Shmanners! [theme music plays] Travis: Hello, internet! I'm your husband host, Travis McElroy. Teresa: And I'm your wife host, Teresa McElroy! Travis: And you're listening to Shmanners! Teresa: It's extraordinary etiquette… Travis: … for ordinary occasions! Hello, my dove. Teresa: Hello, dear. I really liked that joke, is what I wanted to s— Travis: I wish I had made that one up. I didn't— Teresa: —smile at you. My smile was communicating was that that was a great one. Travis: I didn't make that one up. That was from a list, "18 Funny Earth Day Jokes for Kids." Teresa: Nice! Oh, "Click here to print the jokes." [laughs] Travis: I'm not gonna do that. Teresa: [laughs] Travis: Okay. Wow, there's a lot in here! Teresa: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm. Travis: Uh-huh, yeah? Teresa: Oh! What's the difference between weather and climate? Travis: What? Teresa: You can't weather a tree, but you can climb it. Travis: Ahh! Okay. What kind of shorts do clouds wear? Thunderwear! Teresa: Ahh! Travis: Ahh. Teresa: Those are great. Um, tell you what, I always associate Earth Day— uh, I have two things, right? That I think about. I think about the cartoon Captain Planet… Travis: Okay. Teresa: And then I think about—was it—what was the show that there was that, like, aggressive Earth Day green guy. -

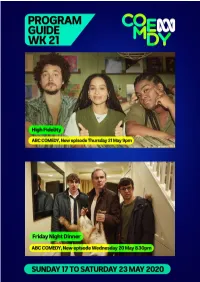

ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 21 Index

ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 21 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 17 May 2020 ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Monday, 18 May 2020 .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 19 May 2020 ........................................................................................................................................ 15 Wednesday, 20 May 2020................................................................................................................................... 21 Thursday, 21 May 2020 ....................................................................................................................................... 27 Friday, 22 May 2020 ............................................................................................................................................ 33 Saturday, 23 May 2020 ....................................................................................................................................... 39 ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 21 Sunday 17 May 2020 Program Guide Sunday, 17 May 2020 5:00am The Hive (Repeat,G) 5:10am Pocoyo (CC,Repeat,G) 5:20am Kiddets (CC,Repeat,G) 5:30am Postman Pat Special Delivery -

How NBC's 30 Rock Parodies and Satirizes The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank TELEVISION REPRESENTING TELEVISION: HOW NBC'S 30 ROCK PARODIES AND SATIRIZES THE CULTURAL INDUSTRIES by LAUREN M. BRATSLAVSKY A THESIS Presented to the School ofJournalism and Communication and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2009 11 "Television Representing Television: How NBC's 30 Rock Parodies and Satirizes the Cultural Industries," a thesis prepared by Lauren M. Bratslavsky in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the School of Journalism and Communication. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Committee in Charge: Carl Bybee, Chair Patricia Curtin Janet Wasko Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Lauren Bratslavsky IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Lauren Bratslavsky for the degree of Master of Science in the School ofJournalism and Communication to be taken June 2009 Title: TELEVISION REPRESENTING TELEVISION: HOW NBC'S 30 ROCK PARODIES AND SATIRIZES THE CULTURAL INDUSTRIES Approved: This project analyzes the cun-ent NBC television situation comedy 30 Rock for its potential as a popular form ofcritical cultural criticism of the NBC network and, in general, the cultural industries. The series is about the behind the scenes work of a fictionalized comedy show, which like 30 Rock is also appearing on NBC. The show draws on parody and satire to engage in an ongoing effort to generate humor as well as commentary on the sitcom genre and industry practices such as corporate control over creative content and product placement. -

Figurenanalyse Der Sitcom “30 Rock”

Bakkalaureatsarbeit Matrikelnummer: 0820483 SE Kontextualisierte AV-Analyse am Beispiel der Entwicklung von Fernsehserien LV-Leitung: Dr. Sascha Trültzsch LV-Nummer: 641.055 15. Februar 2011 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung .............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Begriffsdefinitionen ............................................................................................................. 5 3. Theoretische Grundlagen ................................................................................................... 6 3.1. Analysemodell nach Jens Eder (2008) ....................................................................... 6 3.2. Stereotypgeleitete Figurenkonzeption ......................................................................... 8 3.3. Stereotypgeleitete Figurenrezeption ........................................................................... 9 4. Das Fallbeispiel 30 ROCK ................................................................................................. 11 5. Figurenanalyse anhand des Beispiels 30 ROCK .......................................................... 13 5.1. Hauptfiguren .............................................................................................................. 15 5.1.1. Liz Lemon – Die Karrierefrau ...................................................................... 15 5.1.2. Jack Donaghy – Der Boss .......................................................................... 21 5.1.3. -

美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 the Vocabulary Coverage in American

國立臺灣師範大學英語學系 碩 士 論 文 Master’s Thesis Department of English National Taiwan Normal University 美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 The Vocabulary Coverage in American Television Programs A Corpus-Based Study 指導教授:陳 浩 然 Advisor: Dr. Hao-Jan Chen 研 究 生:周 揚 亭 Yang-Ting Chou 中 華 民 國一百零三年七月 July, 2014 國 立 英 臺 語 灣 師 學 範 系 大 學 103 碩 士 論 文 美 國 影 集 的 字 彙 涵 蓋 量 語 料 庫 分 析 周 揚 亭 中文摘要 身在英語被視為外國語文的環境中,英語學習者很難擁有豐富的目標語言環 境。電視影集因結合語言閱讀與聽力,對英語學習者來說是一種充滿動機的學習 資源,然而少有研究將電視影集視為道地的語言學習教材。許多研究指出媒體素 材有很大的潛力能激發字彙學習,研究者很好奇學習者要學習多少字彙量才能理 解電視影集的內容。 本研究探討理解道地的美國電視影集需要多少字彙涵蓋量 (vocabulary coverage)。研究主要目的為:(1)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,分別需要 英國國家語料庫彙編而成的字族表(the BNC word lists)和匯編英國國家語料庫 (BNC)與美國當代英語語料庫(COCA)的字族表多少的字彙量;(2)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,不同的電視影集類型需要的字彙量;(3)分析出現在美國 影集卻未列在字族表的字彙,並比較兩個字族表(the BNC word lists and the BNC/COCA word lists)的異同。 研究者蒐集六十部美國影集,包含 7,279 集,31,323,019 字,並運用 Range 分析理解美國影集需要分別兩個字族表的字彙量。透過語料庫的分析,本研究進 一步比較兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。 研究結果顯示,加上專有名詞(proper nouns)和邊際詞彙(marginal words),英 國國家語料庫字族表需 2,000 至 7,000 字族(word family),以達到 95%的字彙涵 蓋量;至於英國國家語料庫加上美國當代英語語料庫則需 2,000 至 6,000 字族。 i 若須達到 98%的字彙涵蓋量,兩個字族表都需要 5,000 以上的字族。 第二,有研究表示,適當的文本理解需要 95%的字彙涵蓋量 (Laufer, 1989; Rodgers & Webb, 2011; Webb, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Webb & Rodgers, 2010a, 2010b),為達 95%的字彙涵蓋量,本研究指出連續劇情類(serial drama)和連續超 自然劇情類(serial supernatural drama)需要的字彙量最少;程序類(procedurals)和連 續醫學劇情類(serial medical drama)最具有挑戰性,因為所需的字彙量最多;而情 境喜劇(sitcoms)所需的字彙量差異最大。 第三,美國影集內出現卻未列在字族表的字會大致上可分為四種:(1)專有 名詞;(2)邊際詞彙;(3)顯而易見的混合字(compounds);(4)縮寫。這兩個字族表 基本上包含完整的字彙,但是本研究顯示語言字彙不斷的更新,新的造字像是臉 書(Facebook)並沒有被列在字族表。 本研究也整理出兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。為達 95%字彙涵 蓋量,英國國家語料庫的 4,000 字族加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識才足夠;而 英國國家語料庫合併美國當代英語語料庫加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識只需 3,000 字族即可達到 95%字彙涵蓋量。另外,為達 98%字彙涵蓋量,兩個語料庫 合併的字族表加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識需要 10,000 字族;英國國家語料 庫字族表則無法提供足以理解 98%美國影集的字彙量。 本研究結果顯示,為了能夠適當的理解美國影集內容,3,000 字族加上專有 名詞和邊際詞彙的知識是必要的。字彙涵蓋量為理解美國影集的重要指標之一, ii 而且字彙涵蓋量能協助挑選適合學習者的教材,以達到更有效的電視影集語言教 學。 關鍵字:字彙涵蓋量、語料庫分析、第二語言字彙學習、美國電視影集 iii ABSTRACT In EFL context, learners of English are hardly exposed to ample language input. -

Program Guide

Program Guide Week 30 Sunday July 20th, 2014 5:20 am Latin American News - News via satellite from Television National de Chile, in Spanish, no subtitles. 5:50 am Urdu News - News via satellite from PTV Pakistan in Islamabad, in Urdu, no subtitles. 6:20 am Indonesian News - News via satellite from TVRI Jakarta, in Indonesian, no subtitles. 7:00 am Russian News - News via satellite from NTV Moscow, in Russian, no subtitles. 7:30 am Polish News - Wydarzenia from Polsat in Warsaw via satellite, in Polish, no subtitles. 8:00 am Maltese News - News from Public Broadcasting Services Limited, Malta, in Maltese, no subtitles. 8:30 am Macedonian News - News via satellite from public broadcaster MRT in Skopje, in Macedonian, no subtitles. 9:05 am Croatian News - News via satellite from HRT Croatia, in Croatian, no subtitles. 9:40 am Serbian News - News via satellite from Serbian Broadcasting Corporation, in Serbian, no subtitles. 10:15 am Portuguese News - News via satellite from RTP Portugal (Lisbon), in Portuguese, no subtitles. 11:00 am Hungarian News - News via satellite from Duna TV (DTV) Budapest, in Hungarian, no subtitles. 11:30 am Dutch News - News via satellite from BVN, in Dutch, no subtitles. 12:00 pm Tomorrow's Doctors - This series reveals the dramatic journeys of young medical students on their way to becoming top physicians. It follows their progress in different stages of their education, from working on plastic dummies to dealing with actual patients later in their training. It also captures the highs as well as the inevitable lows that they will experience during their studies.