Captain Biddle's 'Coolness' Commandeers a Sperm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Us Lone Wand'ring Whaling-Men

“Us Lone Wand’ring Whaling-Men”: Cross-cutting Fantasies of Work and Nation in Late Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century American Whaling Narratives by Jennifer Hope Schell B.A., Emory University, 1996 M.A., University of Georgia, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jennifer Hope Schell Jennifer Hope Schell It was defended on April 21, 2006 and approved by Susan Z. Andrade, Associate Professor of English Jean Ferguson Carr, Associate Professor of English Kirk Savage, Associate Professor of History of Art & Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Glazener, Associate Professor of English ii “Us Lone Wand’ring Whaling-Men”: Cross-cutting Fantasies of Work and Nation in Late Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century American Whaling Narratives Jennifer Hope Schell, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 My project takes up a variety of fictional and non-fictional texts about a kind of work which attracted the attention of American novelists Herman Melville, Harry Halyard, and Helen E. Brown; historian Obed Macy; and journalist J. Ross Browne, among others. In my Introduction, I argue that these whaling narratives helped to further develop and perpetuate an already existing fantasy of masculine physical labor which imagines the United States’ working class men to be ideal, heroic Americans. This fantasy was so compelling and palpable that, surprisingly enough, the New England whalemen could be persistently claimed as characteristically and emblematically American, even though they worked on hierarchically-stratified floating factories, were frequently denied their Constitutional rights by maritime law, and hardly ever spent any time on American soil. -

The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex

THE CREW of the ESSEX 0. THE CREW of the ESSEX - Story Preface 1. THE CREW of the ESSEX 2. FACTS and MYTHS about SPERM WHALES 3. KNOCKDOWN of the ESSEX 4. CAPTAIN POLLARD MAKES MISTAKES 5. WHALING LINGO and the NANTUCKET SLEIGH RIDE 6. OIL from a WHALE 7. HOW WHALE BLUBBER BECOMES OIL 8. ESSEX and the OFFSHORE GROUNDS 9. A WHALE ATTACKS the ESSEX 10. A WHALE DESTROYS the ESSEX 11. GEORGE POLLARD and OWEN CHASE 12. SURVIVING the ESSEX DISASTER 13. RESCUE of the ESSEX SURVIVORS 14. LIFE after the WRECK of the ESSEX Frank Vining Smith (1879- 1967) was a prolific artist from Massachusetts who specialized in marine painting. His impressionistic style made his paintings especially beautiful. This image depicts one of his works—a whaleship, like the Essex, sailing “Out of New Bedford.” Leaving Nantucket Island, in August of 1819, the Essex had a crew of 20 men and one fourteen-year-old boy. The ship’s captain was 29-year-old George Pollard, a Nantucket man, who had previously—and successfully—sailed on the Essex as First Mate. This was his first command aboard a whaling ship. Because so many whalers were sailing from Nantucket, by 1819, Pollard and the Essex’s owners had to find crew members who were from Cape Cod and the mainland. In Nantucket parlance, these off-island chaps were called “coofs.” There were numerous coofs aboard the Essex when she left the harbor on August 12, 1819. Viewed as outsiders, by native Natucketers, coofs were not part of the island’s “family.” Even so, working on a whaler—which, by 1819, was both a ship and a factory—African-American crewmen experienced the relative equality of shipboard life. -

Moby-Dick: a Picture Voyage

Moby-Dick A Picture Voyage Library of Congress Cataloging–in–Publication Data Melville, Herman, 1819-1891 Moby-Dick : a picture voyage : an abridged and illustrated edition of the original classic / by Herman Melville ; edited by Tamia A. Burt, Joseph D. Thomas, Marsha L. McCabe ; with illustrations from the New Bedford Whaling Museum. p. cm. ISBN 0-932027-68-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 0-932027-73-3 (Cloth) 1. Melville, Herman, 1819-1891. Moby Dick--Illustrations. 2. Sea stories, American--Illustrations. 3. Whaling ships--Pictoirial works. 4. Whaling--Pictorial works. 5. Whales--Pictorial works. I. Burt, Tamia A. II. Thomas, Joseph D. III. McCabe, Marsha. IV. Title. PS2384.M6 A36 2002 813'.3--dc21 2002009311 © 2002 by Spinner Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Spinner Publications, Inc., New Bedford, MA 02740 Moby-Dick A Picture Voyage An Abridged and Illustrated Edition of the Original Classic by Herman Melville Edited by Tamia A. Burt, Joseph D. Thomas, Marsha L. McCabe with illustrations from The New Bedford Whaling Museum Acknowledgments / Credits Naturally, no serious book concerning the American whaling industry can be done with- out interaction with the New Bedford Whaling Museum. We are grateful to Director Anne Brengle and Director of Programs Lee Heald for their support. We are especially grateful to the Museum’s library staff, particularly Assistant Librarian Laura Pereira and Librarian Michael Dyer, for their energy and helpfulness, and to Collections Manager Mary Jean Blasdale, Curator Michael Jehle, volunteer Irwin Marks, Emeritus Director Richard Kugler, and Photo Archivist Michael Lapides. When we began work on this project, The Kendall Whaling Museum was an indepen- dent entity in Sharon, Massachusetts, and we were fortunate enough to receive the gracious assistance and eminent knowledge of the Kendall’s Director, Stuart M. -

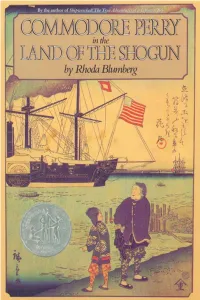

Japan Has Always Held an Important Place in Modern World Affairs, Switching Sides From

Japan has always held an important place in modern world affairs, switching sides from WWI to WWII and always being at the forefront of technology. Yet, Japan never came up as much as China, Mongolia, and other East Asian kingdoms as we studied history at school. Why was that? Delving into Japanese history we found the reason; much of Japan’s history was comprised of sakoku, a barrier between it and the Western world, which wrote most of its history. How did this barrier break and Japan leap to power? This was the question we set out on an expedition to answer. With preliminary knowledge on Matthew Perry, we began research on sakoku’s history. We worked towards a middle; researching sakoku’s implementation, the West’s attempt to break it, and the impacts of Japan’s globalization. These three topics converged at the pivotal moment when Commodore Perry arrived in Japan and opened two of its ports through the Convention of Kanagawa. To further our knowledge on Perry’s arrival and the fall of the Tokugawa in particular, we borrowed several books from our local library and reached out to several professors. Rhoda Blumberg’s Commodore Perry in the Land of the Shogun presented rich detail into Perry’s arrival in Japan, while Professor Emi Foulk Bushelle of WWU answered several of our queries and gave us a valuable document with letters written by two Japanese officials. Professor John W. Dower’s website on MIT Visualizing Cultures offered analysis of several primary sources, including images and illustrations that represented the US and Japan’s perceptions of each other. -

BOOK REVIEWS Sailor-Diplomat: a Biography of Commodore James Biddle, 1783- 1848, by David F

BOOK REVIEWS Sailor-Diplomat: A Biography of Commodore James Biddle, 1783- 1848, By David F. Long. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1983. Pp. xvi, 312. Preface, illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, index. $22.95.) The reputation of Commodore James Biddle, though secure in the environs of Philadelphia, is less wellknown to students of Ameri- can history. If pressed, most could recall the names of Nicholas Biddle, James's brother, who was Andrew Jackson's protagonist in the homeric struggle for the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States in the 1830s. Naval historians might even remember James's uncle Nicholas, whose ship, the U.S.S. Randolph, blew up during a battle with the ship of the line H.M.S. Yarmouth during the Revolutionary war. David F. Long, in a well-written study, details Biddle's accomplishments and explains the reasons for this compara- tive obscurity. "As a professional seafarer," Long concludes, "Biddle can be summed up as superb in navigation, gunnery, courage, and adminis- trative ability" (p. 249). He served as midshipman under Captain William Bainbridge in the U.S.S. Philadelphia during the Barbary wars, enduring months of captivity in Tripoli following the Phila~ delphia's grounding and capture. During the War of 1812, he was first lieutenant aboard the U.S.S. Wasp during her successful engage- ment with H.M.S. Frolic. Subsequently appointed to command of the sloop-of-war U.S.S. Hornet, the vessel's accurate gunnery caused H.M.S. Penguin to strike her colors in an engagement fought in the South Atlantic after the war was over. -

Nantucket Inquirer Bunkerhill.Pdf

http://www.ack.net/BunkerHillfinalist030514.html News Classifieds/Advertising Galleries Real Estate Special Features I&M Publications Visitors Guide Subscribe Contact Us NEWS Philbrick's "Bunker Hill" a New England Society finalist Share Nathaniel Philbrick By Joshua Balling [email protected] , @JBallingIM I&M Staff Writer (March 4, 2014 ) Nantucket author and historian Nathaniel Philbrick's most recent book, "Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution," has been named a finalist for the New England Society's 2014 Book Awards in the Nonfiction-History and Biography category. The awards "honor books of merit that celebrate New England and its culture," according to the New England Society. "Bunker Hill" chronicles the pivotal Boston battle that ignited the American Revolution. Philbrick won the 2000 National Book Award for non-fiction for "In the Heart of the Sea," about the whaleship Essex , struck by a whale in the South Pacific in 1819 It is currently in production as a major motion picture with Ron Howard as director. "Bunker Hill" is up against Jill Lepore's "Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin," and Kevin Cullen and Shelly Murphy's "Whitey Bulger: America's Most Wanted Gangster and the Manhunt that Brought Him to Justice." The winners will be announced in mid-March. For up-to-the-minute information on Nantucket's breaking news, boat and plane cancellations, weather alerts, sports and entertainment news, deals and promotions at island businesses and more, Sign up for Inquirer and Mirror text alerts. Click Here . -

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND of the SHOGUN

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND OF THE SHOGUN by Rhoda Blumberg For my husband, Gerald and my son, Lawrence I want to thank my friend Dorothy Segall, who helped me acquire some of the illustrations and supplied me with source material from her private library. I'm also grateful for the guidance of another dear friend Amy Poster, Associate Curator of Oriental Art at the Brooklyn Museum. · Table of Contents Part I The Coming of the Barbarians 11 1 Aliens Arrive 13 2 The Black Ships of the Evil Men 17 3 His High and Mighty Mysteriousness 23 4 Landing on Sacred Soil The Audience Hall 30 5 The Dutch Island Prison 37 6 Foreigners Forbidden 41 7 The Great Peace The Emperor · The Shogun · The Lords · Samurai · Farmers · Artisans and Merchants 44 8 Clouds Over the Land of the Rising Sun The Japanese-American 54 Part II The Return of the Barbarians 61 9 The Black Ships Return Parties 63 10 The Treaty House 69 11 An Array Of Gifts Gifts for the Japanese · Gifts for the Americans 78 12 The Grand Banquet 87 13 The Treaty A Japanese Feast 92 14 Excursions on Land and Sea A Birthday Cruise 97 15 Shore Leave Shimoda · Hakodate 100 16 In The Wake of the Black Ships 107 AfterWord The First American Consul · The Fall of the Shogun 112 Appendices A Letter of the President of the United States to the Emperor of Japan 121 B Translation of Answer to the President's Letter, Signed by Yenosuke 126 C Some of the American Presents for the Japanese 128 D Some of the Japanese Presents for the Americans 132 E Text of the Treaty of Kanagawa 135 Notes 137 About the Illustrations 144 Bibliography 145 Index 147 About the Author Other Books by Rhoda Blumberg Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Steamships were new to the Japanese. -

A Chat with Author Nathaniel Philbrick ... Life

2/26/2018 A chat with author Nathaniel Philbrick - Entertainment & Life - The Cape Codder - Brewster, MA Entertainment & Life A chat with author Nathaniel Philbrick By Douglas Karlson Posted Nov 27, 2015 at 2:01 AM In the summer of 2014, Nantucket author and historian Nathaniel Philbrick found himself on the deck of Mystic Seaport Museum’s newly restored whaling ship, the Charles W. Morgan, as she sailed through the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary off Provincetown. As he saw whales spouting all around him, Philbrick must have imagined himself a crewmember aboard the ill-fated Essex, the subject of his best-selling book and winner of the 2000 American National Book Award, “In the Heart of the Sea.” The Essex, a Nantucket whaling ship, was rammed and sunk by a sperm whale in the South Pacific in 1819. Crewmembers survived for more than 90 days aboard the ship’s tiny whaleboats, and their tale inspired Herman Melville to write “Moby Dick.” But fans of Philbrick’s book won’t have to sail into Cape Cod Bay aboard a 19th century bark to conjure up images of this epic story of survival at sea, as Academy Award-winning director Ron Howard will bring it to them on big screens across the country on Dec. 11. In advance of that, on Wednesday, December 2, Philbrick will give a talk and sign books at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History. (Tickets are sold out.) Philbrick promised to provide the audience with a “glimpse behind the curtain,” at the making of the movie, for which he also served as a consultant. -

Nat Philbrick Press Release 1.Pages

The Bronxville Historical Conservancy For Immediate Release: January 13, 2014 Contact: Liz Folberth, (914-793-1371), Member, Board of Directors, The Bronxville Historical Conservancy Nathaniel Philbrick, National Book Award Winner and Best-Selling Author To Be Guest Lecturer at Bronxville Historical Conservancy Brendan Gill Lecture Friday, March 7 ! The Bronxville Historical Conservancy will host its 16th Annual Brendan Gill Community Lecture on Friday, March 7, at 8:00 pm in the Sommer Center on the campus of Concordia College, Bronxville, NY. The guest speaker will be Nathaniel Philbrick, New York Times best-selling author who has won numerous awards for his historic tales of America and the sea. His book In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, which detailed the true story of a tragic 1819 voyage that served as inspiration for Herman Melville’s epic tale, won the National Book Award in 2000. His book Mayflower: A Story of Community, Courage and War, was a finalist for the 2007 Pulitzer Prize in History. Philbrick’s most recent book, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution, chronicles the cradle of American Revolution, Boston’s action-packed years of 1771-1776. Reviewers have called Bunker Hill “popular history at its best,” and a book “that resonates with leadership lessons for all times,” dubbing Philbrick an author with a “fine sense of the ambitions that drive people in war and politics.” Philbrick grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and was Brown University’s first intercollegiate All-American sailor. He received an MA in American Literature from Duke University, where he was a James B. -

Diane Ackerman Amy Adams Geraldine Brooks Billy Collins Mark Doty Matt Gallagher Jack Gantos Smith5th Hendersonannual Alice Hoffman Marlon James T

Diane Ackerman Amy Adams Geraldine Brooks Billy Collins Mark Doty Matt Gallagher Jack Gantos Smith5th HendersonAnnual Alice Hoffman Marlon James T. Geronimo Johnson Sebastian Junger Ann Leary Anthony Marra Richard Michelson Valzhyna Mort Michael Patrick O’Neill Evan Osnos Nathaniel Philbrick Diane Rehm Michael Ruhlman Emma Sky Richard Michelson NANTUCKET, MA June 17 - 19, 2016 Welcome In marking our fifth year of the Nantucket Book Festival, we are thrilled with where we have come and where we are set to go. What began as an adventurous idea to celebrate the written word on Nantucket has grown exponentially to become a gathering of some of the most dynamic writers and speakers in the world. The island has a rich literary tradition, and we are proud that the Nantucket Book Festival is championing this cultural imperative for the next generation of writers and readers. Look no further than the Book Festival’s PEN Faulkner Writers in Schools program or our Young Writer Award to see the seeds of the festival bearing fruit. Most recently, we’ve added a visiting author program to our schools, reaffirming to our students that though they may live on an island, there is truly no limit to their imaginations. Like any good story, the Nantucket Book Festival hopes to keep you intrigued, inspired, and engaged. This is a community endeavor, dedicated to enriching the lives of everyone who attends. We are grateful for all of your support and cannot wait to share with you the next chapter in this exciting story. With profound thanks, The Nantucket Book Festival Team Mary Bergman · Meghan Blair-Valero · Dick Burns · Annye Camara Rebecca Chapa · Rob Cocuzzo · Tharon Dunn · Marsha Egan Jack Fritsch · Josh Gray · Mary Haft · Maddie Hjulstrom Wendy Hudson · Amy Jenness · Bee Shay · Ryder Ziebarth Table of Contents Book Signing ......................1 Weekend at a Glance ..........16-17 Schedules: Friday ................2-3 Map of Events .................18-19 Saturday ............ -

Implementation Grants – Mystic Seaport Museum – Voyaging

GI-50615-13 NEH Application Cover Sheet America's Historical and Cultural Organizations PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Susan Funk E-mail:[email protected] Executive Vice President Phone(W): (860) 572-5333 75 Greenmanville Avenue Phone(H): P.O. Box 6000 Fax: (860) 572-5327 Mystic, CT 06355-0990 UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: History - American INSTITUTION Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. Mystic, CT UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Voyaging In the Wake of the Whalers: The 38th Voyage of the Charles W. Morgan Grant Period: From 9/2013 to 2/2016 Field of Project: History - American Description of Project: Mystic Seaport requests a Chairman’s Level implementation grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to fund a suite of online, onsite, offsite, and onboard public programs and exhibits that will provide new national insight into universal and important humanities themes, through an interdisciplinary exploration of historic and contemporary American whaling. The Museum and its partners will explore through this project how, when, and why dominant American perceptions of whales and whaling took their dramatic turns. The project will raise public awareness in New England and nationwide about the role the whaling industry played in the development of our nation’s multi-ethnic make-up, our domestic economy, our global impact and encounters, and our long-standing fascination with whales. And it will promote thought about the nation’s whaling heritage, and how it continues to shape our communities and culture. BUDGET Outright Request $986,553.00 Cost Sharing $1,404,796.00 Matching Request Total Budget $2,391,349.00 Total NEH $986,553.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

Black Ships & Samurai

Perry, ca. 1854 Perry, ca. 1856 © Nagasaki Prefecture by Mathew Brady, Library of Congress On July 8, 1853, residents of Uraga on the outskirts of Edo, the sprawling capital of feudal Japan, beheld an astonishing sight. Four foreign warships had entered their harbor under a cloud of black smoke, not a sail visible among them. They were, startled observers quickly learned, two coal-burning steamships towing two sloops under the command of a dour and imperious American. Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry had arrived to force the long- secluded country to open its doors to the outside world. This was a time that Americans can still picture today through Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick, published in 1851—a time when whale-oil lamps illu- minated homes, baleen whale bones gave women’s skirts their copious form, and much indus- trial machinery was lubricated with the leviathanís oil. For sev- “The Spermacetti Whale” by J. Stewart, 1837 eral decades, whaling ships New Bedford Whaling Museum departing from New England ports had plied the rich fishery around Japan, particularly the waters near the northern island of Hokkaido. They were pro- hibited from putting in to shore even temporarily for supplies, however, and shipwrecked sailors who fell into Japanese hands were commonly subjected to harsh treatment. “Black Ships & Samurai” by John W. Dower — Chapter One, “Introduction” 1 - 1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology © 2008 Visualizing Cultures http://visualizingcultures.mit.edu This situation could not last. “If that double-bolted land,