Macedonia Above All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulgaria's Pirin Mountains

The Pirin Mountains, Bulgaria ABODE OF THE THUNDER GOD 13th - 27th June Introduction The YRC meet to Bulgaria came about after a chance communication from Lizzie Alderson, who runs Pirin Adventures, a company which provides mountaineering, trekking and walking holidays in the Pirin Mountains of Bulgaria. Further conversations with Lizzie in Leeds and some research on the internet confirmed that it would be a novel and extremely interesting location for an overseas meet, with plenty of scope for a fortnight’s hut-to-hut trekking, taking in ridges and summits as we pleased. Named after Perun, the Thracian god of thunder and lightning, the Pirin Mountains are crystalline and located in southwest Bulgaria within the western part of the Rila-Rhodope massif. The Pirin massif slopes southwards and has a width of 30-35km. The main axis is oriented NW-SE with an approximate length of 70km. The northern part of the range comprises the Pirin National Park of 232 square kilometres, which has UNESCO status. The geology is complex but the mountain ridges are mostly granite. The Koncheto ridge and its continuation over Kutelo and Vihren summits are different and comprise marbleised karst with remains of the granite intrusion and some limestone. Limestone is also present around Mt Orelyak to the east. There are over 180 glacial tarns and lakes in Pirin. The Alpine zone scree and rocks are replaced by sub-alpine meadow-bush areas around 2300m and mountain forest between 1000-2000m. This ecological diversity was enhanced by the rapidly ablating snowfields present in June, providing us with an amazing display of flora and fauna. -

The Aromanians in Macedonia

Macedonian Historical Review 3 (2012) Македонска историска ревија 3 (2012) EDITORIAL BOARD: Boban PETROVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editor-in-chief) Nikola ŽEŽOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Dalibor JOVANOVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Toni FILIPOSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Charles INGRAO, Purdue University, USA Bojan BALKOVEC, University of Ljubljana,Slovenia Aleksander NIKOLOV, University of Sofia, Bulgaria Đorđe BUBALO, University of Belgrade, Serbia Ivan BALTA, University of Osijek, Croatia Adrian PAPAIANI, University of Elbasan, Albania Oliver SCHMITT, University of Vienna, Austria Nikola MINOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editorial board secretary) ISSN: 1857-7032 © 2012 Faculty of Philosophy, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje, Macedonia University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius - Skopje Faculty of Philosophy Macedonian Historical Review vol. 3 2012 Please send all articles, notes, documents and enquiries to: Macedonian Historical Review Department of History Faculty of Philosophy Bul. Krste Misirkov bb 1000 Skopje Republic of Macedonia http://mhr.fzf.ukim.edu.mk/ [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 Nathalie DEL SOCORRO Archaic Funerary Rites in Ancient Macedonia: contribution of old excavations to present-day researches 15 Wouter VANACKER Indigenous Insurgence in the Central Balkan during the Principate 41 Valerie C. COOPER Archeological Evidence of Religious Syncretism in Thasos, Greece during the Early Christian Period 65 Diego PEIRANO Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala 85 Denitsa PETROVA La conquête ottomane dans les Balkans, reflétée dans quelques chroniques courtes 95 Elica MANEVA Archaeology, Ethnology, or History? Vodoča Necropolis, Graves 427a and 427, the First Half of the 19th c. -

Nicopolis Ad Nestum and Its Place in the Ancient Road Infrastructure of Southwestern Thracia

BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE, XLIV, 2018 Proceedings of the First International Roman and Late Antique Thrace Conference “Cities, Territories and Identities” (Plovdiv, 3rd – 7th October 2016) Nicopolis ad Nestum and Its Place in the Ancient Road Infrastructure of Southwestern Thracia Svetla PETROVA Abstract: The road network of main and secondary roads for Nicopolis ad Nestum has not been studied comprehensively so far. Our research was carried out in the pe- riod 2010-2015. We have gathered the preserved parts of roads with bridges, together with the results of archaeological studies and data about the settlements alongside these roads. The Roman city of Nicopolis ad Nestum inherited road connections from 1 One of the first descriptions of the pre-Roman times, which were further developed. Road construction in the area has road net in the area of Nevrokop belongs been traced chronologically from the pre-Roman roads to the Roman primary and to Captain A. Benderev (Бендерев 1890, secondary ones for the ancient city. There were several newly built roadbeds that were 461-470). V. Kanchov is the next to follow important for the area and connected Nicopolis with Via Diagonalis and Via Egnatia. the ancient road across the Rhodopes, The elements of infrastructure have been established: primary and secondary roads, connecting Nicopolis ad Nestum with crossings, facilities and roadside stations. Also the locations of custom-houses have the valley of the Hebros river (Кънчов been found at the border between Parthicopolis and Nicopolis ad Nestum. We have 1894, 235-247). The road from the identified a dense network of road infrastructure with relatively straight sections and a Nestos river (at Nicopolis) to Dospat, lot of local roads and bridges, connecting the settlements in the territory of Nicopolis the so-called Trans-Rhodopean road, ad Nestum. -

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800S-1900S

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800s-1900s February 2003 Katrin Bozeva-Abazi Department of History McGill University, Montreal A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Contents 1. Abstract/Resume 3 2. Note on Transliteration and Spelling of Names 6 3. Acknowledgments 7 4. Introduction 8 How "popular" nationalism was created 5. Chapter One 33 Peasants and intellectuals, 1830-1914 6. Chapter Two 78 The invention of the modern Balkan state: Serbia and Bulgaria, 1830-1914 7. Chapter Three 126 The Church and national indoctrination 8. Chapter Four 171 The national army 8. Chapter Five 219 Education and national indoctrination 9. Conclusions 264 10. Bibliography 273 Abstract The nation-state is now the dominant form of sovereign statehood, however, a century and a half ago the political map of Europe comprised only a handful of sovereign states, very few of them nations in the modern sense. Balkan historiography often tends to minimize the complexity of nation-building, either by referring to the national community as to a monolithic and homogenous unit, or simply by neglecting different social groups whose consciousness varied depending on region, gender and generation. Further, Bulgarian and Serbian historiography pay far more attention to the problem of "how" and "why" certain events have happened than to the emergence of national consciousness of the Balkan peoples as a complex and durable process of mental evolution. This dissertation on the concept of nationality in which most Bulgarians and Serbs were educated and socialized examines how the modern idea of nationhood was disseminated among the ordinary people and it presents the complicated process of national indoctrination carried out by various state institutions. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace, 1893-1912 By Martin Valkov Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Tolga Esmer Second Reader: Prof. Roumen Daskalov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The current thesis narrates an important episode of the history of South Eastern Europe, namely the history of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and its demand for political autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. Far from being “ancient hatreds” the communal conflicts that emerged in Macedonia in this period were a result of the ongoing processes of nationalization among the different communities and the competing visions of their national projects. These conflicts were greatly influenced by inter-imperial rivalries on the Balkans and the combination of increasing interference of the Great European Powers and small Balkan states of the Ottoman domestic affairs. I argue that autonomy was a multidimensional concept covering various meanings white-washed later on into the clean narratives of nationalism and rebirth. -

Trajan Belev-Goce

Trajan Belev – Goce By Gjorgi Dimovski-Colev Translated by Elizabeth Kolupacev Stewart 1 The Historical Archive – Bitola and the Municipal Council SZBNOV – Bitola “Unforgotten” Editions By Gjorgi Dimovski–Colev Trajan Belev – Goce Publisher board Vasko Dimovski Tode Gjoreski vice president Zlate Gjorshevski Jovan Kochankovski Aleksandar Krstevski Gjorgji Lumburovski (Master) Cane Pavlovski president Jovo Prijevik Kiril Siljanovski Ilche Stojanovski Gjorgji Tankovski Jordan Trpkovski Editorial Board Stevo Gadzhovski Vasko Dimovski Tode Gjoreski Master Gjorgji Lumburovski chief editor Jovan Kochanovski Aleksandar Krstevski, alternate chief editor Gjorgji Tankovski Reviewers Dr Trajche Grujoski Dr Vlado Ivanovski 2 On the first edition of the series “The Unforgotten.” The history of our people and particularly our most recent history which is closely connected to the communist Party of Yugoslavia and SKOJ bursting with impressive stories of heroism, self-sacrifice, and many other noble human feats which our new generations must learn about. Among the precious example of political consciousness and sacrifice in the great and heroic struggle our future generations do not need to have regard to the distant past but can learn from the actions of youths involved in the living reality of the great liberation struggle. The publication of the series “Unforgotten” represents a program of the Municipal Council of the Union of the fighters of the NOB – Bitola. The series is comprised of many publications of famous people and events from the recent revolutionary past of Bitola and its environs. People who in the Liberation battle and the socialist revolution showed themselves to be heroes and their names and their achievements are celebrated in the “Unforgotten” series by the people. -

"Shoot the Teacher!": Education and the Roots of the Macedonian Struggle

"SHOOT THE TEACHER!" EDUCATION AND THE ROOTS OF THE MACEDONIAN STRUGGLE Julian Allan Brooks Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 1992 Bachelor of Education, University of British Columbia, 200 1 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History O Julian Allan Brooks 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Julian Allan Brooks Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: "Shoot the Teacher!" Education and the Roots of the Macedonian Struggle Examining Committee: Chair: Professor Mark Leier Professor of History Professor AndrC Gerolymatos Senior Supervisor Professor of History Professor Nadine Roth Supervisor Assistant Professor of History Professor John Iatrides External Examiner Professor of International Relations Southern Connecticut State University Date Approved: DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Ecologia Balkanica

ECOLOGIA BALKANICA International Scientific Research Journal of Ecology Volume 6, Issue 2 December 2014 UNION OF SCIENTISTS IN BULGARIA – PLOVDIV UNIVERSITY OF PLOVDIV PUBLISHING HOUSE ii International Standard Serial Number Print ISSN 1314-0213; Online ISSN 1313-9940 Aim & Scope „Ecologia Balkanica” is an international scientific journal, in which original research articles in various fields of Ecology are published, including ecology and conservation of microorganisms, plants, aquatic and terrestrial animals, physiological ecology, behavioural ecology, population ecology, population genetics, community ecology, plant-animal interactions, ecosystem ecology, parasitology, animal evolution, ecological monitoring and bioindication, landscape and urban ecology, conservation ecology, as well as new methodical contributions in ecology. Studies conducted on the Balkans are a priority, but studies conducted in Europe or anywhere else in the World is accepted as well. Published by the Union of Scientists in Bulgaria – Plovdiv and the University of Plovdiv Publishing house – twice a year. Language: English. Peer review process All articles included in “Ecologia Balkanica” are peer reviewed. Submitted manuscripts are sent to two or three independent peer reviewers, unless they are either out of scope or below threshold for the journal. These manuscripts will generally be reviewed by experts with the aim of reaching a first decision as soon as possible. The journal uses the double anonymity standard for the peer-review process. Reviewers do not have to sign their reports and they do not know who the author(s) of the submitted manuscript are. We ask all authors to provide the contact details (including e-mail addresses) of at least four potential reviewers of their manuscript. -

American Protestantism and the Kyrias School for Girls, Albania By

Of Women, Faith, and Nation: American Protestantism and the Kyrias School For Girls, Albania by Nevila Pahumi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Pamela Ballinger, Co-Chair Professor John V.A. Fine, Co-Chair Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Mary Kelley Professor Rudi Lindner Barbara Reeves-Ellington, University of Oxford © Nevila Pahumi 2016 For my family ii Acknowledgements This project has come to life thanks to the support of people on both sides of the Atlantic. It is now the time and my great pleasure to acknowledge each of them and their efforts here. My long-time advisor John Fine set me on this path. John’s recovery, ten years ago, was instrumental in directing my plans for doctoral study. My parents, like many well-intended first generation immigrants before and after them, wanted me to become a different kind of doctor. Indeed, I made a now-broken promise to my father that I would follow in my mother’s footsteps, and study medicine. But then, I was his daughter, and like him, I followed my own dream. When made, the choice was not easy. But I will always be grateful to John for the years of unmatched guidance and support. In graduate school, I had the great fortune to study with outstanding teacher-scholars. It is my committee members whom I thank first and foremost: Pamela Ballinger, John Fine, Rudi Lindner, Müge Göcek, Mary Kelley, and Barbara Reeves-Ellington. -

Balkan Wars Between the Lines: Violence and Civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918

ABSTRACT Title of Document: BALKAN WARS BETWEEN THE LINES: VIOLENCE AND CIVILIANS IN MACEDONIA, 1912-1918 Stefan Sotiris Papaioannou, Ph.D., 2012 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe, Department of History This dissertation challenges the widely held view that there is something morbidly distinctive about violence in the Balkans. It subjects this notion to scrutiny by examining how inhabitants of the embattled region of Macedonia endured a particularly violent set of events: the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War. Making use of a variety of sources including archives located in the three countries that today share the region of Macedonia, the study reveals that members of this majority-Orthodox Christian civilian population were not inclined to perpetrate wartime violence against one another. Though they often identified with rival national camps, inhabitants of Macedonia were typically willing neither to kill their neighbors nor to die over those differences. They preferred to pursue priorities they considered more important, including economic advancement, education, and security of their properties, all of which were likely to be undermined by internecine violence. National armies from Balkan countries then adjacent to geographic Macedonia (Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia) and their associated paramilitary forces were instead the perpetrators of violence against civilians. In these violent activities they were joined by armies from Western and Central Europe during the First World War. Contrary to existing military and diplomatic histories that emphasize continuities between the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War, this primarily social history reveals that the nature of abuses committed against civilians changed rapidly during this six-year period. -

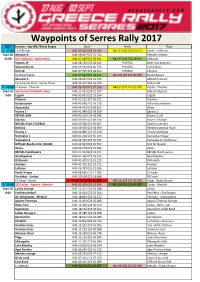

Waypoints of Serres Rally 2017

Waypoints of Serres Rally 2017 DAY Liaisons ‐ Spe+B3:F50cial Stages Start Finish Place 1 ‐ 27.08 L1 Lefkonas N41 06.202 E23 32.936 N41 07.640 E23 29.911 Elpida ‐ Lefkonas Start SS Metochi 9. N41 06.657 E23 31.745 Metochi Stream 15:00 SSS1 Metochi ‐ Melenekitsi N41 07.640 E23 29.911 N41 07.640 E23 29.911 Lefkonas Stream 13 N41 08.741 E23 28.164 PHOTOS After fast downhill Melenikitsi 33 N41 09.532 E23 26.735 PHOTOS In the River Hills 51 N41 07.505 E23 28.813 PHOTOS Christos L2 Hotel Elpida N41 07.640 E23 29.911 N41 06.202 E23 32.936 Elpida Resort Metochi 9. N41 06.657 E23 31.745 Metochi Stream Ceremonial Start ‐ Serres Town N41 05.342 E23 32.940 Volta Café 2 ‐ 28.08 L1 Serres ‐ Therma N41 06.202 E23 32.936 N40 52.973 E23 33.920 Elpida ‐ Therma Start SS SS2 Ayrton Chalkidiki Lakes N41 11.422 E23 31.107 Metochi Bypass 9:00 Lagadi N40 50.661 E23 33.254 Lagadi Potamia N41 21.513 E24 36.311 Potamia Kastanochori N40 49.648 E23 39.370 Palio Kastanochori Asprovalta N40 44.433 E23 40.651 Sikies Vrasna 2 N40 41.946 E23 39.659 Egnatia 1 REFUEL ELIN N40 40.139 E23 40.548 Stayros ELIN Stavros N40 39.095 E23 40.674 Stavros Change REFUEL Point STAVROS N40 40.238 E23 39.867 Stavros Junction Rentina N40 39.405 E23 36.909 Rentina National Road Vrasna 2 N40 42.886 E23 37.230 Vrasna Old Road Vamvakia 1 N40 41.268 E23 36.633 Vamvakia Village Vamvakia 2 N40 42.365 E23 35.335 Vamvakia to Arethousa Difficult Washout for QUADS N40 42.592 E23 25.657 SOS for Quads! Askos N40 44.259 E23 22.692 Askos REFUEL Nymfopetra N40 41.592 E23 19.711 REFUEL Nymfopetra Nymfopetres