The Washington Street Urban Renewal Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

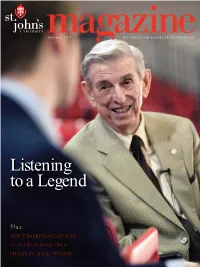

Listening to a Legend

Summer 2011 For Alumni and Friends of the University Listening to a Legend Plus: MEN'S BASKETBALL SENIORS 10 YEARS BARNES ARICO MULLIN TO HALL OF FAME first glance The Thrill Is Back It was a season of renewed excitement as the Red Storm men’s basketball team brought fans to their feet and returned St. John’s to a level of national prominence reminiscent of the glory days of old. Midway through the season, following thrilling victories over nationally ranked opponents, students began poking good natured fun at Head Coach Steve Lavin’s California roots by dubbing their cheering section ”Lavinwood.” president’s message Dear Friends, As you are all aware, St. John’s University is primarily an academic institution. We have a long tradition of providing quality education marked by the uniqueness of our Catholic, Vincentian and metropolitan mission. The past few months have served as a wonderful reminder, fan base this energized in quite some time. On behalf of each and however, that athletics are also an important part of the St. John’s every Red Storm fan, I’d like to thank the recently graduated seniors tradition, especially our storied men’s basketball program. from both the men’s and women’s teams for all their hard work and This issue of theSt. John’s University Magazine pays special determination. Their outstanding contributions, both on and off the attention to Red Storm basketball, highlighting our recent success court, were responsible for the Johnnies’ return to prominence and and looking back on our proud history. I hope you enjoy the profile reminded us of how special St. -

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

Sonya Sklaroff

SONYA SKLAROFF WWW.SONYASKLAROFF.COM SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Galerie Anagama, Versailles, France 2018 Galerie Ferrari, Vevey, Switzerland Galerie Sparts, Paris, France 2017 Galerie Anagama, Versailles, France 2016 Galerie Sparts, Paris, France Galerie Next, Toulouse, France 2015 Galerie Anagama, Versailles, France 2014 Galerie Sparts, Paris, France 2013 Galerie Anagama, Versailles, France 2011 Galerie Sparts, Paris, France 2010 Jenkins Johnson Gallery, New York, NY 2009 Galerie Sparts, Paris, France David Findlay Galleries, New York, NY 2008 The Gallery at Steuben Glass, New York, NY Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2007 Corning Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Sparts, Paris, France 2006 David Findlay Gallery, New York, NY Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2005 Water Street Gallery, New York, NY 2004 David Findlay Gallery, New York, NY Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2003 French Institute Alliance Francaise, New York, NY Sofitel Lafayette Square, Washington, DC 2002 French Consulate, New York, NY Steuben, New York, NY Cartier, New York, NY 2001 Gale-Martin Fine Art, New York, NY Steuben, New York, NY 2000 & 1999 Allen Sheppard Gallery, New York, NY 1997 & 1995 Gallery at Roundabout, New York, NY TWO AND THREE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 Portland Art Gallery, Portland, ME 2010 Maison de la Culture, Neuilly sur Seine, France 2002 RISD Works Gallery, Providence, RI SVG Collection, Nantucket, MA 2001 Media Gallery, Boston, MA SVG Collection, Nantucket, MA 1999 Gallery at Roundabout, New York, NY 611 Broadway #717 New -

Robert and Anne Dickey House Designation Report

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 28, 2005, Designation List 365 LP-2166 ROBERT and ANNE DICKEY HOUSE, 67 Greenwich Street (aka 28-30 Trinity Place), Manhattan. Built 1809-10. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 19, Lot 11. On October 19, 2004, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Robert and Anne Dickey House and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing was continued to April 21, 2005 (Item No. 1). Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Sixteen people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of State Assemblyman Sheldon Silver, the Lower Manhattan Emergency Preservation Fund, Municipal Art Society of New York, New York Landmarks Conservancy, Historic Districts Council, and Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Two of the building’s owners, and five of their representatives, testified against designation. In addition, the Commission received numerous communications in support of designation, including a resolution from Manhattan Community Board 1 and letters from City Councilman Alan J. Gerson, the Northeast Office of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Preservation League of New York State, and architect Robert A.M. Stern. The building had been previously heard by the Commission on October 19, 1965, and November 17, 1965 (LP-0037). Summary The large (nearly 41 by 62 feet), significantly intact Federal style town house at No. 67 Greenwich Street in lower Manhattan was constructed in 1809-10 when this was the most fashionable neighborhood for New York’s social elite and wealthy merchant class. -

Mount Morris Park Historic District Extension Designation Report

Mount Morris Park Historic District Extension Designation Report September 2015 Cover Photograph: 133 to 143 West 122nd Street Christopher D. Brazee, September 2015 Mount Morris Park Historic District Extension Designation Report Essay Researched and Written by Theresa C. Noonan and Tara Harrison Building Profiles Prepared by Tara Harrison, Theresa C. Noonan, and Donald G. Presa Architects’ Appendix Researched and Written by Donald G. Presa Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Daniel Heinz Watts Commissioners Meenakshi Srinivasan, Chair Frederick Bland John Gustafsson Diana Chapin Adi Shamir-Baron Wellington Chen Kim Vauss Michael Devonshire Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Sarah Carroll, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Jared Knowles, Director of Preservation Lisa Kersavage, Director of Special Projects and Strategic Planning TABLE OF CONTENTS MOUNT MORRIS PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION MAP .................... AFTER CONTENTS TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING .............................................................................................. 1 MOUNT MORRIS PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION BOUNDARIES .................................... 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 3 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE MOUNT MORRIS PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION Early History and Development of the Area ................................................................................ -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Todos Los Toros Y Osos De La Bolsa Port

TODOS LOS TOROS Y OSOS DE LA BOLSA Ricardo A. Fornero Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Revisado y ampliado 2018 1 2 TODOS LOS TOROS Y OSOS DE LA BOLSA Las palabras y su materialización 4 Esculturas bursátiles del toro y el oso 5 Esculturas bursátiles del toro 5 Un toro que sacude el mundo 6 1709 Las palabras bears y bulls para designar a los bajistas y los alcistas en la Bolsa 8 1924 El toro y el oso , de Isidore Bonheur, en la Bolsa de Nueva York 17 Ventana: Una escultura con un tema similar al de la obra de Bonheur 1931 El toro y el oso en la entrada del edificio fallido de la Bolsa de De- 21 troit 1985 Bulle und Bär , el toro y el oso de Frankfurt 24 1987 En la Plaza de la Bolsa de Hong Kong no hay toros, sino búfalos 26 1988 Toro y oso en el interior de la Bolsa de Singapur 27 Ventana: M Bull, el otro toro de Singapur 1989 Charging bull , el toro de Wall Street 31 1994 El primer toro bursátil en Corea se instala en una firma de inversión 35 1995 Una escultura de toro y oso para el nuevo edificio de la Bolsa de Estambul 36 1997 El oso y el toro de la Bursa Malaysia 38 2002 El toro coreano de la Asociación de Inversión 40 2003 El toro en Bull Ring, Birmingham: Una simbolización comercial, no una representación bursátil 42 2004 Los dos toros de la Bolsa de Shenzhen y la escultura del buey pio- nero 44 2004 El toro y el oso de la Bolsa en una estampilla de Luxemburgo 49 3 2005 Korea Exchange como mercado consolidado y los toros de la Bolsa de Corea 51 2005 El toro de Sofía y el cambio del logotipo de la Bolsa búlgara 54 2005 Toro y oso en -

Exposure and Information 2014 Fall

Exposure & Information The Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Library Newsletter Insurance * Risk Management * Actuarial Science Fall 2014 Vol 3, Issue 2 In This Issue Greetings! A New Chapter Begins Welcome to the Fall 2014 issue of our newsletter, Center for Professional Education Fall "Exposure and Information." "E & I" is directed to our Schedule academic community, members, donors, and Kwon. "Collegiate Education in Risk prospective members. This publication provides Management and Insurance information about our history, services, recent acquisitions, and activities as well as events from the Globally." School of Risk Management, Insurance and Actuarial Walker."Strategy and Culture Still Science, the Center for Professional Education, and the Need Work." Ellen Thrower Center for Apprenticeship and Career Services. SRM Alumni Event Social Media A New Chapter Begins for the Historic Kathryn & Davis Library Membership Shelby Collum Davis Library by Ricky Waller. The St. John's University Davis Library began a new chapter in Quick Links its history opening the Fall 2014 Davis Library Web site semester in September at its School of Risk Management new location at 101 Astor Place. Center for Professional Education Faculty, students and staff are Kathryn & Shelby Cullom integrating into our new "East Davis Library Village" neighborhood. The campus is located in a brand St. John's University new "Gold LEED Certified" building, surrounded by 3 101 Astor Pl., 2nd fl. other major universities Cooper Union, NYU and The New New York, NY 10003 (212) 277 5135 - ph School for Social Research, all within a 10 block radius. (212) 277 5140 - fx There are a seemingly unlimited number of eclectic restaurant eateries, city parks, and green markets in the area that help give this new location of SJU Manhattan Campus a unique and exciting vibe. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Saving Carnegie Hall: A Case Study of Historic Preservation in Postwar New York City Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3x19f20h Author Schmitz, Sandra Elizabeth Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Saving Carnegie Hall: A Case Study of Historic Preservation in Postwar New York A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Sandra Elizabeth Schmitz June 2015 Thesis Committee: Dr. Patricia Morton, Chairperson Dr. Jason Weems Dr. Catherine Gudis Copyright by Sandra Elizabeth Schmitz 2015 The Thesis of Sandra Elizabeth Schmitz is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Patricia Morton, for helping me to arrive at this topic and for providing encouragement and support along the way. I’m incredibly grateful for the time she took to share her knowledgeable insight and provide thorough feedback. Committee members Dr. Jason Weems and Dr. Catherine Gudis also brought valuable depth to my project through their knowledge of American architecture, urbanism, and preservation. The department of Art History at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) made this project possible by providing me with a travel grant to conduct research in New York City. Carnegie Hall’s archivists graciously guided my research at the beginning of this project and provided more information than I could fit in this thesis. I could not have accomplished this project without the support of Stacie, Hannah, Leah, and all the friends who helped me stay grounded through the last two years of writing, editing, and talking about architecture. -

Midnight in Manhattan Students Hit the Streets to Help Those in Need

ALumni mT.AgAzine ohn’S S J FALL 2013 Midnight in Manhattan Students Hit the Streets to Help Those in need Fr. LeveSque WeLcomed | neW SJu BrAnd | 16TH AnnuAL PreSidenT’S dinner FIRST GLANCE Students Celebrate SJU During the first week of the fall semester, members of the Freshman Class got into the spirit of St. John’s by gathering on the Great Lawn of the Queens campus to take their place in University history. The newest members of the St. John’s family arranged themselves in a living formation of the recently unveiled new SJU logo. 2 ST. JoHn’S univerSiTy ALumni mAgAzine To watch the time-lapse video of our students forming the new logo, please visit www.stjohns.edu/fall13mag FALL 2013 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Dear Friends, As many of you are aware, I was formally installed as President of St. John’s University this past September, and I am honored to serve. As a member and as Chair of the University’s Board of Trustees for many years, I know the traditions and rich history of this institution, and I am committed to continuing both. When I arrived back in August, one of my top priorities was much greater detail. As you will see, our young men and to meet the St. John’s community — to go out and speak with women are profoundly impacted by service and, once they the students, alumni, faculty, administrators and staff who graduate, carry the Vincentian spirit with them to communities comprise this magnificent institution. And thanks to events near and far. -

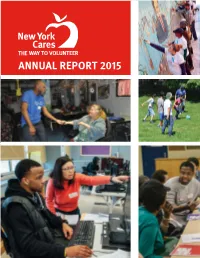

Annual Report 2015 2 Annual Report 2015 3 Table of Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS A Letter from Our Leaders 5 A Year in Numbers 6 The Power of Volunteers 9 Improving Education 10 Meeting Immediate Needs 13 Revitalizing Public Spaces 14 Community Partners 2015 16 Financial Supporters 2015 26 Financial Statement 2015 32 Board of Directors 34 New York Cares Staff 35 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 5 A LETTER FROM OUR LEADERS DEAR FRIENDS We are proud to report that 2015 marked another year of continued growth for New York Cares. A record 63,000 New Yorkers expanded the impact of our volunteer- led programs at 1,350 nonprofits and public schools citywide. These caring individuals ensured that the life-saving and life-enriching services our programs offer are delivered daily to New Yorkers living at or below the poverty line. Thanks to the generous support we received from people like you, our volunteers accomplished a great deal, including: Education: • reinforcing reading and math skills in 22,000 elementary school students • tutoring more than 1,000 high school juniors for their SATs • preparing 20,000 adults for the workforce Immediate needs: • serving 550,000 meals to the hungry (+10% vs. the prior year) • collecting 100,000 warm winter coats–a record number not seen since Hurricane Sandy • helping 19,000 seniors avoid the debilitating effects of social isolation Revitalization of public spaces: Paul J. Taubman • cleaning, greening and painting more than 170 parks, community gardens and schools Board President We are equally proud of the enormous progress made in serving the South Bronx, Central Brooklyn and Central Queens through our Focus Zone initiative. -

2018 CCPO Annual Report

Annual Concession Report of the City Chief Procurement Officer September 2018 Approximate Gross Concession Registration Concession Agency Concessionaire Brief Description of Concession Revenues Award Method Date/Status Borough Received in Fiscal 2018 Concession property is currently used for no other Department of purpose than to provide waterborne transportation, Citywide James Miller emergency response service, and to perform all Sole Source $36,900 2007 Staten Island Administrative Marina assosciated tasks necessary for the accomplishment Services of said purposes. Department of DCAS concession property is used for no other Citywide Dircksen & purpose than additional parking for patrons of the Sole Source $6,120 10/16/2006 Brooklyn Administrative Talleyrand River Café restaurant. Services Department of Citywide Williamsburgh Use of City waterfront property for purposes related to Sole Source $849 10/24/2006 Queens Administrative Yacht Club the operation of the yacht club. Services Department of Skaggs Walsh owns property adjacent to the Citywide Negotiated Skaggs Walsh permitted site. They use this property for the loading $29,688 7/10/2013 Queens Administrative Concession and unloading of oil and accessory business parking. Services Department of Concession property is currently used for the purpose Citywide Negotiated Villa Marin, GMC of storing trailers and vehicle parking in conjunction $74,269 7/10/2013 Staten Island Administrative Concession with Villa Marin's car and truck dealership business. Services Department of Concession