Why Don't More American Indians Become Engineers in South Dakota?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe Tribal State Gaming Compact

GAMING COMPACT BETWEEN THE FLANDREAU SANTEE SIOUX TRIBE AND THE STATE OF SOUTH DAKOTA WHEREAS, the Tribe is a federally recognized Indian Tribe whose reservation is located in Moody County, South Dakota; and WHEREAS, Article III of the Flandreau Santee Sioux Constitution provides that the governing body of the Tribe shall be the Executive Committee; and WHEREAS, Article VIII, Section 1, of the Constitution authorizes the Executive Committee to negotiate with the State government; and WHEREAS, the State has, through constitutional provisions and legislative acts, authorized limited card games, slot machines, craps, roulette and keno activities to be conducted in Deadwood, South Dakota; and WHEREAS, the Congress of the United States has enacted the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, Public Law 100-497, 102 Stat. 2426, 25 U.S.C. 2701, et seq. (1988), which permits Indian tribes to operate Class III gaming activities on Indian reservations pursuant to a Tribal-State Compact entered into for that purpose; and WHEREAS, the Tribe operates gaming activities on the Flandreau Santee Sioux Indian Reservation, at the location identified in section 9.5 in Moody County, South Dakota; and WHEREAS, the Tribe and the State desire to negotiate a Tribal-State Compact to permit the continued operation of such gaming activities; and NOW, THEREFORE, in consideration of the foregoing, the Tribe and the State hereto do promise, covenant, and agree as follows: 1. DECLARATION OF POLICY In the spirit of cooperation, the Tribe and the State hereby set forth a joint effort to implement the terms of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. The State recognizes the positive economic benefits that continued gaming may provide to the Tribe. -

Smoke Signals Volume 2

June 2006 Smoke Signals Volume 2 Table of Contents 2006 BIA TFM Students Celebrate TFM Graduates 1 Graduation! Administration 2 ~Dave Koch Aviation 3 Fire Use/Fuels 5 Operations 7 Prevention 10 Budget 11 Training 12 Director 16 Left to right; Treon Fleury, Range Technician, Crow Creek Agency; Emily Cammack, Fuels Specialist, Southern Ute Agency; Donald Povatah, Fire Management Officer, Hopi Agency. Five BIA students completed the final requirements of the 18-month Technical Fire Management Program (TFM) in April. TFM is an academic program designed to improve the technical proficiency of fire and natural resource management specialists. The curriculum is rigorous and includes subjects such as statistics, economics, fuels management, fire ecology, and fire management Left; Kenneth Jaramillo, Assistant Fire Management Officer, Southern Pueblos Agency; Right: Ray Hart, Fuels Specialist, planning. Blackfeet Agency. The program is designed for GS 6-11 employees who intend to pursue a career in fire and currently occupy positions such as assistant fire management officer, fuels management specialist, wildland fire operations specialist, engine foreman, hotshot superintendent, and others. TFM targets applicants who lack a 4-year biological science, agriculture, or natural resources management degree. Students who successfully complete TFM are awarded 18 upper division college credits, which contribute toward the education requirements necessary for federal jobs in the 401 occupational series. As such, the program is considered a convenient “bridge to profession” for our fire management workforce. Continued next page Administration Page 2 TFM is administered by the TFM is not a requirement to obtain information. The deadline for Washington Institute, a Seattle based one of these positions. -

Our Native Americans Volume 3

OUR NATIVE AMERICANS VOLUME 3 WHERE AND HOW TO FIND THEM by E. KAY KIRKHAM GENEALOGIST All rights reserved Stevenson's Genealogy Center 230 West 1230 North Provo, Utah 84604 1985 Donated in Memory of Frieda McNeil 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction .......................................... ii Chapter 1. Instructions on how to use this book ............ 1 How do I get started? ..................... 2 How to use the pedigree form ............... 3 How to use a library and its records .......... 3 Two ways to get help ...................... 3 How to take notes for your family record ....... 4 Where do we go from here? ................ 5 Techniques in searching .................... 5 Workshop techniques ..................... 5 Chapter 2. The 1910 Federal Census, a listing of tribes, reservations, etc., by states .................. 7 Chapter 3. The 1910 Federal Census, Government list- ing of linguistic stocks, with index ........... 70 Chapter 4. A listing of records by agency ............. 123 Chapter 5. The American Tribal censuses, 1885-1940 ............................ 166 Chapter 6. A Bibliography by tribe .................. 203 Chapter 7. A Bibliography by states ................. 211 Appendix A. Indian language bibliography .............. 216 Appendix B. Government reports, population of tribes, 1825, 1853, 1867, 1890, 1980 .............. 218 Appendix C. Chart for calculating Indian blood .......... 235 Appendix D. Pedigree chart (sample) .................. 236 Appendix E. Family Group Sheet (sample) ............. 237 Appendix F. Religious records among Native Americans ... 238 Appendix G. Allotted tribes, etc. ..................... 242 Index ............................. .... 244 ii INTRODUCTION It is now six years since I started to satisfy my interest in Native American research and record- making for them as a people. While I have written extensively in the white man's way of record- making, my greatest satisfaction has come in the three volumes that have now been written about our Native Americans. -

Legislative Resolution 234

LR 234 LR 234 ONE HUNDREDTH LEGISLATURE SECOND SESSION LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION 234 Introduced by Chambers, 11. Read first time January 25, 2008 Committee: Judiciary WHEREAS, Congress, by the Act of August 15, 1953, codified at 18 U.S.C. 1162 and 28 U.S.C. 1360, generally known as Public Law 280, ceded federal jurisdiction to the State of Nebraska over offenses committed by or against Indians and civil causes of action between Indians or to which Indians are parties that arise in Indian country in Nebraska; and WHEREAS, Congress subsequently enacted the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968, which included a provision codified at 25 U.S.C. 1323 that authorizes the federal government to accept a retrocession of criminal or civil jurisdiction from the states subject to Public Law 280; and WHEREAS, the State of Nebraska has retroceded much of the jurisdiction it acquired over tribal lands under Public Law 280 back to the federal government, including all civil and criminal jurisdiction within the Santee Sioux Reservation, LR 17, Ninety-seventh Legislature, 2001; all criminal jurisdiction within the Winnebago Reservation, LR 57, Eighty-ninth Legislature, -1- LR 234 LR 234 1986; and criminal jurisdiction within that part of the Omaha Indian Reservation located in Thurston County, except for offenses involving the operation of motor vehicles on public roads or highways within the reservation, LR 37, Eightieth Legislature, 1969; and WHEREAS, the partial retrocession of criminal jurisdiction over the Omaha Indian Reservation has created confusion for -

1 Title South Dakota Indian Reservations Today—Native Students. Grade Level Adult Workshop for Native Inmates. Theme Duration

Title South Dakota Indian Reservations Today—Native Students. Grade Level Adult workshop for Native inmates. Theme Duration 1½ hours. Goal Participants will increase their understanding of the geographical locations and differences among the tribes living on the South Dakota reservations. Objectives Workshop participants will know: 1. The number of reservations in SD. 2. Which tribes live on those reservations. 3. Where the reservations are located. 4. Which two reservations are the largest in population and which reservation is the smallest. 5. Which bands live on which reservations. South Dakota Standards Cultural Concept Participants should recognize the diversity of the SD reservations. Cultural Background The reservations in South Dakota are populated by the seven tribes of the Oceti Sakowin, The Seven Council Fires. Those tribes, who began as one tribe, are now divided into three major language dialect groups: the Dakota, the Nakota, and the Lakota. They are often called the Sioux. According to their oral tradition, they originated as a people at Wind Cave in South Dakota and have always lived in that general area. At the time of European contact, the people lived in Minnesota. The word Dakota means “Considered-friends.” Before they separated, the Dakota lived in the area around Lake Mille Lac in Minnesota, where they would come together for winter camp. Over time they separated into the Oceti Sakowin “Seven Council Fires” as they traveled further away to hunt and no longer camped together in the winter. The tribes came together periodically for ceremonies. The seven sacred ceremonies are the basis of differentiating these tribes from other tribes, which do not have all seven of the ceremonies. -

Tribal Brownfields and Response Programs Respecting Our Land, Revitalizing Our Communities

Tribal Brownfields and Response Programs Respecting Our Land, Revitalizing Our Communities United States Environmental Protection Agency 2013 Purpose This report highlights how tribes are using U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Brownfields Program funding to address contaminated land in Indian country1 and other tribal lands. It also highlights the challenges tribes face. It provides a historic overview of EPA’s Brownfields Program, as it relates to tribes, and demonstrates EPA’s commitment to the development of tribal capacity to deal effectively with contaminated lands in Indian country. The report includes examples of tribal successes to both highlight accomplishments and serve as a resource for ideas, information and reference. 1 Use of the terms “Indian country,” “tribal lands,” and “tribal areas within this document is not intended to provide legal guidance on the scope of any program being described, nor is their use intended to expand or restrict the scope of any such programs, or have any legal effect. 3 Table of Contents Overview .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Brownfields Tribal Highlights and Results .................................................................................................................... 7 EPA Region 1 Brownfields Grantees ........................................................................................................................... 9 Passamaquoddy -

The Role of Western Massachusetts in the Development of American Indian Education Reform Through the Hampton

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1992 The oler of western Massachusetts in the development of American Indian education reform through the Hampton Institute's summer outing program (1878-1912). Deirdre Ann Almeida University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Almeida, Deirdre Ann, "The or le of western Massachusetts in the development of American Indian education reform through the Hampton Institute's summer outing program (1878-1912)." (1992). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4831. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4831 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN INDIAN EDUCATION REFORM THROUGH THE HAMPTON INSTITUTE’S SUMMER OUTING PROGRAM (1878 - 1912) A Dissertation Presented by DEIRDRE ANN ALMEIDA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION September 1992 School of Education @ Copyright by DEIRDRE ANN ALMEIDA 1992 All Rights Reserved THE ROLE OF WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN INDIAN EDUCATION REFORM THROUGH THE HAMPTON INSTITUTE’S SUMMER OUTING PROGRAM (1878 - 1912) A Dissertation Presented by DEIRDRE ANN ALMEIDA To my mother, Esther Almeida and to my daughter, Mariah Almeida-American Horse i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people for their support in the research and development of this dissertation: Dr. -

NHPA) Applies to the Issuance of a UIC Permit (40 CFR § 144.4)

The Environmental Protection Agency National Historic Preservation Act Draft Compliance and Review Document for the Proposed Dewey-Burdock In-Situ Uranium Recovery Project January 20, 2017 Introduction As part of the Underground Injection Control (UIC) permitting process, the Environmental Protection Agency is required to consider whether section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) applies to the issuance of a UIC permit (40 CFR § 144.4). The EPA has determined that the NHPA, which requires federal agencies to take into account the effects of their undertakings on historic properties, applies to its consideration of a UIC permit for the proposed Dewey-Burdock Uranium In- Situ Recovery (ISR) Project (Project). This document describes the status of the EPA’s review and consultation process under section 106 and the 36 CFR Part 800 regulations issued by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), and how the EPA plans to complete that process. The EPA is coordinating its NHPA review efforts with other required federal reviews. 36 CFR § 800.3(b). Initial Steps in the NHPA Section 106 Process As an activity requiring federal approval, the Project is a federal undertaking. 36 CFR §§ 800.3, 800.16(y). Further, the EPA has determined that this undertaking has the potential to cause effects on historic properties. 36 CFR § 800.3(a). Because the Site is not located on tribal lands (as they are defined in the ACHP regulations at 36 CFR § 800.16(x)), the EPA is consulting with the South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). 36 CFR §§ 800.2(c)(1) and 800.3(c). -

Retelling Allotment: Indian Property Rights and the Myth of Common Ownership

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 54 Issue 4 Issue 4 - May 2001 Article 2 5-2001 Retelling Allotment: Indian Property Rights and the Myth of Common Ownership Kenneth H. Bobroff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth H. Bobroff, Retelling Allotment: Indian Property Rights and the Myth of Common Ownership, 54 Vanderbilt Law Review 1557 (2001) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol54/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Retelling Allotment: Indian Property Rights and the Myth of Common Ownership Kenneth H. Bobroff 54 Vand. L. Rev. 1559 (2001) The division of Native American reservations into indi- vidually owned parcels was an unquestionable disaster. Authorized by the General Allotment Act of 1887, allotment cost Indians two-thirds of their land and left much of the re- mainder effectively useless as it passed to successive genera- tions of owners. The conventional understanding, shared by scholars, judges, policymakers, and activists alike, has been that allotment failed because it imposed individual ownership on people who had never known private property. Before al- lotment, so this story goes, Indians had always owned their land in common. Because Indians had no conception of pri- vate property, they were unable to adjust to the culture of pri- vate land rights and were easy targets for non-Indians anxious to acquire their land. -

Sioux and Ponka Indians Missouri River

REPORT OF A VISIT TO THE SIOUX AND PONKA INDIANS ON THE MISSOURI RIVER, MADE BY WM. WELSH. JULY, 1872. [text] PHILADELPHIA: M'CALLA & STAVEY, PRINTERS, N.E. COR. SIXTH AND COMMERCE STS. 1872 [2] blankpage [3] DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR. WASHINGTON, D. C., July 10th, 1872 DEAR SIR: I have received, and read with great satisfaction, your valuable and interesting Report of the 8th instant, in regard to the Indian Agencies that have been assigned to the board of Missions of the Protestant Episcopal Church. I have not time to refer to it in detail, but I wish to say that the facts which you have presented, and the suggestions made, are of great value to our Indian Service, and I trust the Report will have a wide circulation. I feel sure that this report will strengthen the faith of all right minded persons, and create new zeal in the breasts of those who believe that truth, justice and humanity, are sure to be rewarded by Omnipotence. I am, very truely yours, C. DELANO, HON. WILLIAM WELSH, Secretary Philadelphia, Pa [4] blank page [5] PHILADELPHIA, July 8th, 1872. TO THE HON. COLUMBUS DELANO, Secretary of the Interior, Washington: MY DEAR SIR: I returned to this city on the 4th inst., after spending more than six weeks in an official visitation to most of the Indian Agencies, that were, about eighteen months since, placed by the United States Government, under the control of the Board of Missions of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Although my visitation was made at the request of that Missionary Board, yet as the Church is merely the representative of the Government in nominating and supervising Indian Agents, there is an obvious propriety in making a semi-official report to you, especially as governmental action is asked for. -

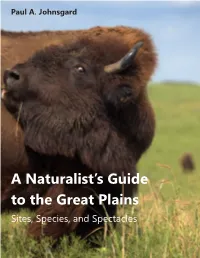

A Naturalist's Guide to the Great Plains

Paul A. Johnsgard A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles This book documents nearly 500 US and Canadian locations where wildlife refuges, na- ture preserves, and similar properties protect natural sites that lie within the North Amer- ican Great Plains, from Canada’s Prairie Provinces to the Texas-Mexico border. Information on site location, size, biological diversity, and the presence of especially rare or interest- ing flora and fauna are mentioned, as well as driving directions, mailing addresses, and phone numbers or internet addresses, as available. US federal sites include 11 national grasslands, 13 national parks, 16 national monuments, and more than 70 national wild- life refuges. State properties include nearly 100 state parks and wildlife management ar- eas. Also included are about 60 national and provincial parks, national wildlife areas, and migratory bird sanctuaries in Canada’s Prairie Provinces. Numerous public-access prop- erties owned by counties, towns, and private organizations, such as the Nature Conser- vancy, National Audubon Society, and other conservation and preservation groups, are also described. Introductory essays describe the geological and recent histories of each of the five mul- tistate and multiprovince regions recognized, along with some of the author’s personal memories of them. The 92,000-word text is supplemented with 7 maps and 31 drawings by the author and more than 700 references. Cover photo by Paul Johnsgard. Back cover drawing courtesy of David Routon. Zea Books ISBN: 978-1-60962-126-1 Lincoln, Nebraska doi: 10.13014/K2CF9N8T A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles Paul A. -

Northern Ponca and Santee Sioux Allotment Survey

Nebraska Historic Resources Intensive Survey of Northern Ponca and Santee Sioux Allotment Properties Prepared for Ponca Tribe of Nebraska Santee Sioux Tribe of Nebraska Nebraska State Historical Society Prepared by Thomas Witt, Sean Doyle, and Jason Marmor SWCA Environmental Consultants 295 Interlocken Boulevard, Suite 300 Broomfield, Colorado 80021 303.487.1183 August 20, 2010 Nebraska Historic Resources Intensive Survey of Northern Ponca and Santee Sioux Allotment Properties ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS SWCA Environmental Consultants (SWCA) would like to thank the following groups and individuals for their help in the completion of this report. From the Nebraska State Historical Society: Bob Puschendorf for his help in facilitating communication with the Northern Ponca and the Santee Sioux, for his help with local promotion of the project, as well as for his knowledge and expertise in the review of this report; and Patrick Haynes for his knowledge and expertise in the architectural review of the survey. From the Northern Ponca: Stanford “Sandy” Taylor for his help in compiling historical information regarding the Northern Ponca during the allotment period, as well as for sharing his own personal experiences, and family history in compiling the historical background for this report. From the Santee Sioux Tribe: Clarence Campbell for his help in identifying former allotment properties on the Santee Sioux Reservation, and for sharing his knowledge and experiences of the families who lived during the allotment period; Franky Jackson for his valuable comments to the report, and for his help tracking down additional historical information; Ramona Frazier and Darlene Crow for their contributions to the historical backgrounds of their families allotment properties; Butch Denny for his help in facilitating communication between SWCA and local Santee residents during the field survey; and the residents of the allotment houses currently on occupied properties for their patience in allowing us to record these resources.