Chapter 4 Three Villages Under the Russian-American Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

Kodiak Alutiiq Heritage Thematic Units Grades K-5

Kodiak Alutiiq Heritage Thematic Units Grades K-5 Prepared by Native Village of Afognak In partnership with: Chugachmiut, Inc. Kodiak Island Borough School District Alutiiq Museum & Archaeological Repository Native Educators of the Alutiiq Region (NEAR) KMXT Radio Station Administration for Native Americans (ANA) U.S. Department of Education Access additional resources at: http://www.afognak.org/html/education.php Copyright © 2009 Native Village of Afognak First Edition Produced through an Administration for Native Americans (ANA) Grant Number 90NL0413/01 Reprint of edited curriculum units from the Chugachmiut Thematic Units Books, developed by the Chugachmiut Culture and Language Department, Donna Malchoff, Director through a U.S. Department of Education, Alaska Native Education Grant Number S356A50023. Publication Layout & Design by Alisha S. Drabek Edited by Teri Schneider & Alisha S. Drabek Printed by Kodiak Print Master LLC Illustrations: Royalty Free Clipart accessed at clipart.com, ANKN Clipart, Image Club Sketches Collections, and drawings by Alisha Drabek on pages 16, 19, 51 and 52. Teachers may copy portions of the text for use in the classroom. Available online at www.afognak.org/html/education.php Orders, inquiries, and correspondence can be addressed to: Native Village of Afognak 115 Mill Bay Road, Suite 201 Kodiak, Alaska 99615 (907) 486-6357 www.afognak.org Quyanaasinaq Chugachmiut, Inc., Kodiak Island Borough School District and the Native Education Curriculum Committee, Alutiiq Museum, KMXT Radio Station, & the following Kodiak Contributing Teacher Editors: Karly Gunderson Kris Johnson Susan Patrick Kathy Powers Teri Schneider Sabrina Sutton Kodiak Alutiiq Heritage Thematic Units Access additional resources at: © 2009 Native Village of Afognak http://www.afognak.org/html/education.php Table of Contents Table of Contents 3 Unit 4: Russian’s Arrival (3rd Grade) 42 Kodiak Alutiiq Values 4 1. -

Federal Register/Vol. 82, No. 215/Wednesday

51860 Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 215 / Wednesday, November 8, 2017 / Notices part 990, NEPA, the Consent Decree, the Administrative Record passcode is 9793554. Additional Final PDARP/PEIS, the Phase III ERP/ The documents comprising the information is available at www.doi.gov/ PEIS and the Phase V ERP/EA. Administrative Record for the Draft OST/ITARA. The Florida TIG is considering the Phase V.2 RP/SEA can be viewed FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Ms. second phase of the Florida Coastal electronically at http://www.doi.gov/ Elizabeth Appel, Director, Office of Access Project in the Draft Phase V.2 deepwaterhorizon/administrativerecord. Regulatory Affairs & Collaborative Action, Office of the Assistant RP/SEA to address lost recreational Authority opportunities in Florida caused by the Secretary—Indian Affairs, at Deepwater Horizon oil spill. In the Draft The authority of this action is the Oil [email protected] or (202) 273– Phase V.2 RP/SEA, the Florida TIG Pollution Act of 1990 (33 U.S.C. 2701 et 4680. proposes one preferred alternative, the seq.) and its implementing Natural SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: OST was Salinas Park Addition, which involves Resource Damage Assessment established in the Department by the the acquisition and enhancement of a regulations found at 15 CFR part 990 American Indian Trust Fund 6.6-acre coastal parcel. The Florida and the National Environmental Policy Management Reform Act of 1994 (1994 Coastal Access Project was allocated Act of 1969 (42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq.). Act), Public Law 103–412, when approximately $45.4 million in early Kevin D. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Russians' Instructions, Kodiak Island, 1784, 1796

N THE FIRST PERMANENT Library of Congress ORUSSIAN SETTLEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA _____ * Kodiak Island Two documents: 1786, 1794_______ 1786. INSTRUCTIONS from Grigorii Shelikhov, founder of the settlement on Kodiak Okhotsk Island, to Konstantin Samoilov, his chief manager, Kodiak Island Three Saints Bay for managing the colony during Shelikhov’s voyage to Okhotsk, Russia, on business of the Russian- American Company. May 4, 1786. [Excerpts] Map of the Russian Far East and Russian America, 1844 . With the exception of twelve persons who [Karta Ledovitago moria i Vostochnago okeana] are going to the Port of Okhotsk, there are 113 Russians on the island of Kytkak [Kodiak]. When the Tri Sviatitelia [Three Saints] arrives from Okhotsk, the crews should be sent to Kinai and to Shugach. Add as many of the local pacified natives as possible to strengthen the Russians. In this manner we can move faster along the shore of the American mainland to the south toward California. With the strengthening of the Russian companies in this land, try by giving them all possible favors to bring into subjection to the Russian Imperial Throne the Kykhtat, Aliaksa, Kinai and Shugach people. Always take an accurate count of the population, both men and women, detail, Kodiak Island according to clans. When the above mentioned natives are subjugated, every one of them must be told that people who are loyal and reliable will prosper under the rule of our Empress, but that all rebels will be totally exterminated by Her strong hand. The purpose of our institutions, whose aim is to bring good to all people, should be made known to them. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

The Following Reviews Express the Opinions of the Individual Reviewers Regarding the Strengths, Weaknesses, and Value of The

REVIEWS EDITED BY M. ROSS LEIN Thefollowing reviews express the opinions of theindividual reviewers regarding the strengths, weaknesses, and value of thebooks they review. As such,they are subjective evaluations and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of theeditors or any officialpolicy of theA.O.U.--Eds. The Florida Scrub Jay: demographyof a cooper- geneticparents in the care of young that are not off- ative-breeding bird.--Glen E. Woolfenden and John spring of the helpers.To establishthat an individual W. Fitzpatrick. 1984. Princeton, New Jersey,Prince- is a helper, one must observeit caring for young that ton University Press. xiv + 406 pp., 1 color plate, are known not to be its own. There is no evidence many figures.ISBN 0-691-08366-5(cloth), 0-691-08367-3 in the chapter on procedures that Woolfenden and (paper).Cloth, $45.00;paper, $14.50.--For nearly two Fitzpatrick employed this criterion, although they decades three long-term studies of communally were aware of it (p. 4). Instead, throughout the book breeding birds, well known to readersof this review, jays are divided into breedersand helpers, implying have been in progress.The behavioral ecology of that if a bird is not a breeder it must be a helper these speciesis so complex that conclusionsreached ("Helpers are nonbreeders," p. 80). It is well known after only a few years of study can be quite mislead- for other speciesthat not all nonbreeders help, and ing. Eachnew year of studynot only enlargessample that individual nonbreedersvary significantlyin the sizesbut also provides insights that require impor- amount or intensity of their helping efforts. -

A Brief Look at the History and Culture of Woody Island, Alaska

A Brief Look At The History April 25 and Culture of Woody Island, 2010 Alaska This document is intended to be a brief lesson on the prehistory and history of Woody Island and the Kodiak Archipelago. It is also intended to be used as a learning resource for fifth graders who By Gordon Pullar Jr. visit Woody Island every spring. Introduction Woody Island is a peaceful place with a lush green landscape and an abundance of wild flowers. While standing on the beach on a summer day a nice ocean breeze can be felt and the smell of salt water is in the air. The island is covered by a dense spruce forest with a forest floor covered in thick soft moss. Woody Island is place where one can escape civilization and enjoy the wilderness while being only a 15 minute boat ride from Kodiak. While experiencing Woody Island today it may be hard for one to believe that it was once a bustling community, even larger in population than the City of Kodiak. The Kodiak Archipelago is made up of 25 islands, the largest being Kodiak Island. Kodiak Island is separated from mainland Alaska by the Shelikof Strait. Kodiak Island is approximately 100 miles long and 60 miles wide and is the second largest island in the United States behind the “big” island of Hawaii. The city of Kodiak is the largest community on the island with a total population of about 6,000 (City Data 2008), and the entire Kodiak Island Borough population is about 13,500 people (Census estimate 2009). -

Clarence Leroy Andrews Books and Papers in the Sheldon Jackson Archives and Manuscript Collection

Clarence Leroy Andrews Books and Papers in the Sheldon Jackson Archives and Manuscript Collection ERRATA: based on an inventory of the collection August-November, 2013 Page 2. Insert ANDR I RUSS I JX238 I F82S. Add note: "The full record for this item is on page 108." Page6. ANDR I RUSS I V46 /V.3 - ANDR-11. Add note: "This is a small booklet inserted inside the front cover of ANDR-10. No separate barcode." Page 31. ANDR IF I 89S I GS. Add note: "The spine label on this item is ANDR IF I 89S I 84 (not GS)." Page S7. ANDR IF I 912 I Y9 I 88. Add note: "The spine label on this item is ANDR IF/ 931 I 88." Page 61. Insert ANDR IF I 931 I 88. Add note: "See ANDR IF I 912 I Y9 I 88. Page 77. ANDR I GI 6SO I 182S I 84. Change the date in the catalog record to 1831. It is not 1931. Page 100. ANDR I HJ I 664S I A2. Add note to v.1: "A" number in book is A-2S2, not A-717. Page 103. ANDR I JK / 86S. Add note to 194S pt. 2: "A" number in book is A-338, not A-348. Page 10S. ANDR I JK I 9S03 I A3 I 19SO. Add note: "A" number in book is A-1299, not A-1229. (A-1229 is ANDR I PS/ S71 / A4 I L4.) Page 108. ANDR I RUSS I JX I 238 / F82S. Add note: "This is a RUSS collection item and belongs on page 2." Page 1SS. -

Kodiak Statistical Areas

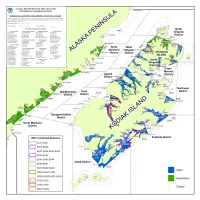

ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Cape Douglas COMMERCIAL FISHERIES DIVISION KODIAK MANAGEMENT AREA HERRING STATISTICAL CHART This chart is a general guide for pennit holders, tender operators, processors, and other industry personnel for illustration of the location of districts and sections used in the managing of the Kodiak Area herringfisheries. For exact descriptions of the district and section boundaries consult the current Commercial Herring Fishing Regulations (Article 8. Kodiak Area). State Water Boundaries - District Boundaries - Section Boundaries - -------- SAC ROE STATISTICAL AREAS NM10 ALITAK DISTRICT INNER MARMOT DISTRICT NORTHEAST DISTRICT UGANIK DISTRICT ALI O Outer Alitak IM IO Monashka- Mill Bay NEI0 Womens Bay UG 10 Kupreanof AL20 Inner A!itak IM20 Anton Larsen NE20 Kalsin Bay UG20 Viekoda 1' AL21 Inner Deadman Bay [M30 Sharatin Bay NE30 Middle Bay UG2 1 Terror Bay Cape Chiniak AL22Outer Dead1mn Bay IM40 Kizhuyak Bay N E40 Inshore Chiniak UG30 Village Islands AL30 Su!ua Bay IM50 Spruce Island NE50 Offshore Chiniak-Manmt UG3 1 West Uganik Passage AL40 Lower O lga Bay UG32 Northeast Ann Uganik AL4 l East Upper Olga Bay NORTll AFOGNAK DISTRICT NORTH MAINLAND UG33 East Arm Uganik ALSO West Upper Olga Bay NAI0 Shuyak Island DISTRICT UG34 South Ann Ugaoik AL60 Geese-Twoheaded NA20 De!phin Bay NMJ0 Hallo Bay UG40 Ou1er Uganik NA30 Perenosa Bay N M20 Inner K ukak NA40 EASTSIDE DISTRICT NA40 Seal Bay NM30 Outer Kukak UYAK DISTRICT EA IO Kaiugnak N A50 Tonki Bay NM40 Missak UYIO Oflshore Uyak Seal Bay EA20 Southwest Sitkalidak UY20 Harvester Island North EA.21 Three Saints Bay WEST AFOGNAK DISTRICT MID-MAINLAND UY30 Inner Uyak Bay EA22 Newman Bay WA IO Raspberry Strait DISTRICT UY3 1 Larsen Bay Mainland EA.23 West Sitk.alidak WA20 Malina Bay MM IO Inner Katmai UY32 Browns Lagoon EA24 Barling Bay WA3 1 ParamanofBay MM20 Outer Katmai UY 40 Zachar Bay Cape Ugyak EA3 0 East Sitkalidak WA32 Foul Bay MM30 Alinchak UY50 Spiridon Bay District EA3 l Tanginak Anchorage WA40 Bluefox Bay MM40 Puale Bay EA40 Outer Sitkalidak WA50 Oflshore W. -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast. -

Technical Report Number 74, Prepared by Impact Assessment Inc

-5 E”/4A FL OCS Study MMS 86-0035 U.S. Department of the Interior Technical Report Number 121 ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::,:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:. :.:+:.:.: :.:. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Social and Economic . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Studies Program . .. .. .. .. .. .. %..%. ....%... .. .. .. .. :.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:. :.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.. .. .. .. .. ..%...... :.:.:.:.:.:... .. .. .. .. .. :.:.:.>~.:.. .. .. .. .. .:.:.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..%....... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Sponsor: +.:.:.:++:.*.:.. .:.:.:.:. Minerals Management :.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:,:.:.:.:.:. .. .. .. ....%%%.... .. .. .. .. .. Service . .../ . %........%%. .. .. .:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:...~.:.:.~.:.:.:.:.: :.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.: .:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.: .::jj:. .: Alaska Outer A@%%$ Continental . ...? --4:.:.:.:.:.: . Shelf Region TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 121 CONTWCT NUMBER 14-12-0001-30186 A SOCIOCULTURAL DESCRIPTION OF SMALL COMJNITIES IN THE KCHIIAK-SHU?IAGIN REGION Prepared for MINERALS MANAGEMENT SERVICE ALASKA OUTER CONTINENTAL SHELF REGION LEASING AND ENVIRONMENT OFFICE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC STUDIES PROGRAM by CULTURAL DYNAMICS, LTD. August 15, 1986 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its content or use thereof. A Sociocultural Description of Small Communities in the Kodiak-Shumagin