Technical Report Number 74, Prepared by Impact Assessment Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kodiak Alutiiq Heritage Thematic Units Grades K-5

Kodiak Alutiiq Heritage Thematic Units Grades K-5 Prepared by Native Village of Afognak In partnership with: Chugachmiut, Inc. Kodiak Island Borough School District Alutiiq Museum & Archaeological Repository Native Educators of the Alutiiq Region (NEAR) KMXT Radio Station Administration for Native Americans (ANA) U.S. Department of Education Access additional resources at: http://www.afognak.org/html/education.php Copyright © 2009 Native Village of Afognak First Edition Produced through an Administration for Native Americans (ANA) Grant Number 90NL0413/01 Reprint of edited curriculum units from the Chugachmiut Thematic Units Books, developed by the Chugachmiut Culture and Language Department, Donna Malchoff, Director through a U.S. Department of Education, Alaska Native Education Grant Number S356A50023. Publication Layout & Design by Alisha S. Drabek Edited by Teri Schneider & Alisha S. Drabek Printed by Kodiak Print Master LLC Illustrations: Royalty Free Clipart accessed at clipart.com, ANKN Clipart, Image Club Sketches Collections, and drawings by Alisha Drabek on pages 16, 19, 51 and 52. Teachers may copy portions of the text for use in the classroom. Available online at www.afognak.org/html/education.php Orders, inquiries, and correspondence can be addressed to: Native Village of Afognak 115 Mill Bay Road, Suite 201 Kodiak, Alaska 99615 (907) 486-6357 www.afognak.org Quyanaasinaq Chugachmiut, Inc., Kodiak Island Borough School District and the Native Education Curriculum Committee, Alutiiq Museum, KMXT Radio Station, & the following Kodiak Contributing Teacher Editors: Karly Gunderson Kris Johnson Susan Patrick Kathy Powers Teri Schneider Sabrina Sutton Kodiak Alutiiq Heritage Thematic Units Access additional resources at: © 2009 Native Village of Afognak http://www.afognak.org/html/education.php Table of Contents Table of Contents 3 Unit 4: Russian’s Arrival (3rd Grade) 42 Kodiak Alutiiq Values 4 1. -

Federal Register/Vol. 82, No. 215/Wednesday

51860 Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 215 / Wednesday, November 8, 2017 / Notices part 990, NEPA, the Consent Decree, the Administrative Record passcode is 9793554. Additional Final PDARP/PEIS, the Phase III ERP/ The documents comprising the information is available at www.doi.gov/ PEIS and the Phase V ERP/EA. Administrative Record for the Draft OST/ITARA. The Florida TIG is considering the Phase V.2 RP/SEA can be viewed FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Ms. second phase of the Florida Coastal electronically at http://www.doi.gov/ Elizabeth Appel, Director, Office of Access Project in the Draft Phase V.2 deepwaterhorizon/administrativerecord. Regulatory Affairs & Collaborative Action, Office of the Assistant RP/SEA to address lost recreational Authority opportunities in Florida caused by the Secretary—Indian Affairs, at Deepwater Horizon oil spill. In the Draft The authority of this action is the Oil [email protected] or (202) 273– Phase V.2 RP/SEA, the Florida TIG Pollution Act of 1990 (33 U.S.C. 2701 et 4680. proposes one preferred alternative, the seq.) and its implementing Natural SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: OST was Salinas Park Addition, which involves Resource Damage Assessment established in the Department by the the acquisition and enhancement of a regulations found at 15 CFR part 990 American Indian Trust Fund 6.6-acre coastal parcel. The Florida and the National Environmental Policy Management Reform Act of 1994 (1994 Coastal Access Project was allocated Act of 1969 (42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq.). Act), Public Law 103–412, when approximately $45.4 million in early Kevin D. -

Russians' Instructions, Kodiak Island, 1784, 1796

N THE FIRST PERMANENT Library of Congress ORUSSIAN SETTLEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA _____ * Kodiak Island Two documents: 1786, 1794_______ 1786. INSTRUCTIONS from Grigorii Shelikhov, founder of the settlement on Kodiak Okhotsk Island, to Konstantin Samoilov, his chief manager, Kodiak Island Three Saints Bay for managing the colony during Shelikhov’s voyage to Okhotsk, Russia, on business of the Russian- American Company. May 4, 1786. [Excerpts] Map of the Russian Far East and Russian America, 1844 . With the exception of twelve persons who [Karta Ledovitago moria i Vostochnago okeana] are going to the Port of Okhotsk, there are 113 Russians on the island of Kytkak [Kodiak]. When the Tri Sviatitelia [Three Saints] arrives from Okhotsk, the crews should be sent to Kinai and to Shugach. Add as many of the local pacified natives as possible to strengthen the Russians. In this manner we can move faster along the shore of the American mainland to the south toward California. With the strengthening of the Russian companies in this land, try by giving them all possible favors to bring into subjection to the Russian Imperial Throne the Kykhtat, Aliaksa, Kinai and Shugach people. Always take an accurate count of the population, both men and women, detail, Kodiak Island according to clans. When the above mentioned natives are subjugated, every one of them must be told that people who are loyal and reliable will prosper under the rule of our Empress, but that all rebels will be totally exterminated by Her strong hand. The purpose of our institutions, whose aim is to bring good to all people, should be made known to them. -

A Brief Look at the History and Culture of Woody Island, Alaska

A Brief Look At The History April 25 and Culture of Woody Island, 2010 Alaska This document is intended to be a brief lesson on the prehistory and history of Woody Island and the Kodiak Archipelago. It is also intended to be used as a learning resource for fifth graders who By Gordon Pullar Jr. visit Woody Island every spring. Introduction Woody Island is a peaceful place with a lush green landscape and an abundance of wild flowers. While standing on the beach on a summer day a nice ocean breeze can be felt and the smell of salt water is in the air. The island is covered by a dense spruce forest with a forest floor covered in thick soft moss. Woody Island is place where one can escape civilization and enjoy the wilderness while being only a 15 minute boat ride from Kodiak. While experiencing Woody Island today it may be hard for one to believe that it was once a bustling community, even larger in population than the City of Kodiak. The Kodiak Archipelago is made up of 25 islands, the largest being Kodiak Island. Kodiak Island is separated from mainland Alaska by the Shelikof Strait. Kodiak Island is approximately 100 miles long and 60 miles wide and is the second largest island in the United States behind the “big” island of Hawaii. The city of Kodiak is the largest community on the island with a total population of about 6,000 (City Data 2008), and the entire Kodiak Island Borough population is about 13,500 people (Census estimate 2009). -

Chapter 4 Three Villages Under the Russian-American Company

Chapter 4 Three Villages Under the Russian-American Company n the years following Cook’s voyage, people living in Makushin, Kashega, and Biorka found their options reduced as trade in I Russian America was soon dominated by the activities of Grigorii I. Shelikhov, a man with voracious interest in the wealth of the territory and a vision of permanent settlements.1 In 1781 he and two other merchants had formed a company that gradually absorbed and drove out smaller competitors while creating powerful allies in Russia. In 1790 he hired the legendary Alexander Baranov, who, forced to the wall by a series of business failures, reluctantly agreed to Shelikhov’s persistent overtures. Baranov sailed from Okhotsk on the Three Saints for the settlement Shelikhov had founded on Kodiak in 1784. Approaching Unalaska Island, the vessel Grigorii I. Shelikhov anchored in Kashega Bay to replenish its water supply. An early October http://en.wikipedia. storm blew in, however, and cornered the vessel, placing it in imminent org/wiki/Grigory_ Shelekhov#mediaviewer/ danger. The crew managed to unload a portion of the cargo during low File:Grigory_Shelikov.jpg tide before the vessel capsized during the night of October 6, stranding everyone for the winter. Baranov’s account of Unalaska in general and Kashega in particular portrayed a demoralized and innervated population. Along with other negative pronouncements, Baranov wrote: —“in general they are all lazy and untidy” —“their yurts are poor and cold” —“they have no fires…except in their oil lamps” —they seldom cook anything —they rarely wear shoes —“they observe no religious laws” —“they know nothing of their origin” —they rarely share food with each other 2 —“where there are no Russians…they make no effort at all” CHAPTER 4: Three villaGES under THE RUSSIAN-American CHAPTER Compan TITLEY 45 His account was strikingly different from those made by Cook’s expedition. -

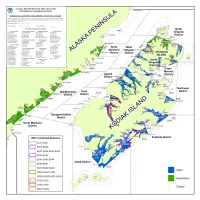

Kodiak Statistical Areas

ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Cape Douglas COMMERCIAL FISHERIES DIVISION KODIAK MANAGEMENT AREA HERRING STATISTICAL CHART This chart is a general guide for pennit holders, tender operators, processors, and other industry personnel for illustration of the location of districts and sections used in the managing of the Kodiak Area herringfisheries. For exact descriptions of the district and section boundaries consult the current Commercial Herring Fishing Regulations (Article 8. Kodiak Area). State Water Boundaries - District Boundaries - Section Boundaries - -------- SAC ROE STATISTICAL AREAS NM10 ALITAK DISTRICT INNER MARMOT DISTRICT NORTHEAST DISTRICT UGANIK DISTRICT ALI O Outer Alitak IM IO Monashka- Mill Bay NEI0 Womens Bay UG 10 Kupreanof AL20 Inner A!itak IM20 Anton Larsen NE20 Kalsin Bay UG20 Viekoda 1' AL21 Inner Deadman Bay [M30 Sharatin Bay NE30 Middle Bay UG2 1 Terror Bay Cape Chiniak AL22Outer Dead1mn Bay IM40 Kizhuyak Bay N E40 Inshore Chiniak UG30 Village Islands AL30 Su!ua Bay IM50 Spruce Island NE50 Offshore Chiniak-Manmt UG3 1 West Uganik Passage AL40 Lower O lga Bay UG32 Northeast Ann Uganik AL4 l East Upper Olga Bay NORTll AFOGNAK DISTRICT NORTH MAINLAND UG33 East Arm Uganik ALSO West Upper Olga Bay NAI0 Shuyak Island DISTRICT UG34 South Ann Ugaoik AL60 Geese-Twoheaded NA20 De!phin Bay NMJ0 Hallo Bay UG40 Ou1er Uganik NA30 Perenosa Bay N M20 Inner K ukak NA40 EASTSIDE DISTRICT NA40 Seal Bay NM30 Outer Kukak UYAK DISTRICT EA IO Kaiugnak N A50 Tonki Bay NM40 Missak UYIO Oflshore Uyak Seal Bay EA20 Southwest Sitkalidak UY20 Harvester Island North EA.21 Three Saints Bay WEST AFOGNAK DISTRICT MID-MAINLAND UY30 Inner Uyak Bay EA22 Newman Bay WA IO Raspberry Strait DISTRICT UY3 1 Larsen Bay Mainland EA.23 West Sitk.alidak WA20 Malina Bay MM IO Inner Katmai UY32 Browns Lagoon EA24 Barling Bay WA3 1 ParamanofBay MM20 Outer Katmai UY 40 Zachar Bay Cape Ugyak EA3 0 East Sitkalidak WA32 Foul Bay MM30 Alinchak UY50 Spiridon Bay District EA3 l Tanginak Anchorage WA40 Bluefox Bay MM40 Puale Bay EA40 Outer Sitkalidak WA50 Oflshore W. -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast. -

Tlcbt Quarttrlp

· .,:' ::...._... - ..... .:.....:...:~ - :':.' :.: - .. .....:.... ~ tlCbt .a~bington /!}i~torical Quarttrlp RUSSIAN PLANS FOR AMERICAN DOMINION When Gregory Ivanovich Shelikof established his trading post at Three Saints Bay on the 3rd day of August 1784 it was not an ordinary venture of a common fur trader to gather a few skins for a temporary prqfit. It was part of a far-reaching plan devised for the extension of Russian dominion over the larger part of the western coast of what is now Canada and the United States. This plan was in his mind at the time he made his preparation for his return voyage, if not before he left Russia. It is not necessary to go farther Ito prove this than to take extracts from Russian records that outline the scheme and follow the development of it to its partial consummation. The Russian hunters and traders had been advancing for a hundred years, crossing Siberia over the broad steppes and the frozen tundra. They had pushed out on the waters of the Pa cific to the southeast coast of Alaska; they had explored the Aleutian Islands; and now Shelikof had established a permanent post on the island of Kadiak. It was yet twenty years before Lewis and Clark made their winter stay at the mouth of the Columbia River, and seven years before Vancouver made his surveys of the southeastern coast of Alaska, or Alexander Mackenzie came by land to tide water near Bella Coola. On May 22, 1786, Shelikof went to sea on his return voy age to Siberia, leaving Samoilof, one of the leaders of his fur traders (promishileniki), in command of his establishment on the island. -

EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK the Foundation of Any Company Is Its Employees, Who Are Committed to Excellence and Guided by Common Principles

EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK The foundation of any company is its employees, who are committed to excellence and guided by common principles. Afognak Native Corporation Employee Handbook Revised 11/23/2020 DISCLAIMER This handbook is designed to acquaint you with Afognak Native Corporation and the Alutiiq people, and to provide you with information about working conditions, company values, employee benefits, and the policies affecting your employment (collectively referred to as “policies”) adopted by Afognak Native Corporation (sometimes referred to as the “Company” or “ANC”). These ANC policies are applicable to individuals employed by ANC, and also to ANC’s direct and indirect subsidiaries at any level (including Alutiiq, LLC and its direct and indirect subsidiaries), and any joint ventures or other business enterprises of those companies, to the extent that those companies and entities formally adopt these policies. For each such company or entity that adopts these policies, the terms “Afognak Native Corporation,” “ANC,” “Company” and “employer” herein shall also refer to each such company and entity, and the terms “employee” and “employees” herein shall also refer to all employees of any such company or entity. Please note that some subsidiaries, joint ventures and other business enterprises of Afognak Native Corporation, Alutiiq, LLC or their subsidiaries might adopt policies and/or provide or offer their employees benefits which are different from, or in addition to, the policies and benefits in this handbook. Please consult with the Human Resources Department for information about the particular policies, individual benefits and leave provided by your particular employer. It is the employee’s responsibility to read, understand, and comply with all policies of this handbook and any other policies that have been adopted by your particular employer. -

GOOD MORNING: 08/14/17 Farm Directionанаvantrump Report

Tim Francisco <[email protected]> GOOD MORNING: 08/14/17 Farm Direction VanTrump Report 1 message Kevin Van Trump <[email protected]> Mon, Aug 14, 2017 at 7:25 AM To: Kevin Van Trump <[email protected]> " People who help others are not trying to be useful, but are leading a useful life. They rarely give advice, but rather only good examples." Paul Coelho MONDAY, AUGUST 14, 2017 Printable Copy or Audio Version Morning Summary: Investors continue to grapple with the ongoing tensions between the U.S. and North Korea, but as we return from the weekend there seems to be a slightly reduced possibility of war. Late Sunday, U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson wrote that the Trump administration was continuing to seek diplomatic solutions to seek the “irreversible denuclearization” of North Korea. In return the stock market is higher and trying to regain some of last weeks losses. I should note that the cryptocurrency "Bitcoin" continues to surge higher, now trying north of $4,000 dollars, quadrupling it's value this year, and up over +40% in just the first few weeks of August. Traders have also turned decidedly more bearish against the U.S. dollar, as large traders are now holding their highest net short positions since the Spring of 2014. On the economic front, there are really no major reports due out today and no scheduled Fed speakers. Earnings wise, nearly threequarters of S&P 500 companies have reported and topped earnings estimates, showing they are on track for +10% growth. -

Alaska Volume 5

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-259 Community Profiles for North Pacific Fisheries - Alaska Volume 5 by A. Himes-Cornell, K. Hoelting, C. Maguire, L. Munger-Little, J. Lee, J. Fisk, R. Felthoven, C. Geller, and P. Little U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Fisheries Science Center November 2013 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS The National Marine Fisheries Service's Alaska Fisheries Science Center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest Fisheries Center. The NMFS-NWFSC series is currently used by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center. This document should be cited as follows: Himes-Cornell, A., K. Hoelting, C. Maguire, L. Munger-Little, J. Lee, J. Fisk, R. Felthoven, C. Geller, and P. 2013. Community profiles for North Pacific fisheries - Alaska. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-259, Volume 5, 210 p. Reference in this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-259 Community Profiles for North Pacific Fisheries - Alaska Volume 5 by A. Himes-Cornell, K. Hoelting, C. Maguire, L. Munger-Little, J. Lee, J. Fisk, R. Felthoven, C. Geller, and P. Little Alaska Fisheries Science Center Resource Ecology and Fisheries Assessment Division Economics and Social Sciences Research Program 7600 Sand Point Way N.E. -

The Westfield Philatelist Newsletter of the Westfield Stamp Club American Philatelic Society Chapter #540 American Topical Association Chapter #113

The Westfield Philatelist Newsletter of the Westfield Stamp Club American Philatelic Society Chapter #540 American Topical Association Chapter #113 Volume 12 Number 2 November/December 2018 Upcoming Meetings Awards Received by Members November 29, 2018 –”First Bureau 2¢ Issues 1894–1903: Shades & Identification”. NOJEX–ASDA October 19–21, 2018, By Lindley Wood, Jr. East Rutherford, NJ Roger Brody –”Embossed Stamped Revenue Paper 1755–1856/ Financing the New Nation” (Gold; ASDA George Washington. President’s Award) 1895 (Scott 267, type III) Louis Caprario -”The 1908 Christmas Seal – The First National Issue” (Gold; American Philatelic Congress Award) December 20, 2018 – “Annual Holiday Party Allan Fisk - (1) “Cunard Queens Visit New York” (Sil- & Donation Auction”. ver) (2) “Gettysburg – The Battle, The Address” (Silver- Bronze; American Topical Society Single Frame Award) [There will be a small philatelic exhibit related to Christmas.] Edward Grabowski - (1) “ The Era of the French Colo- nial Allegorical Group Type: Madagascar & Dependen- cies” (Large Gold; Sidney Schneider Memorial Award) (2) “The Era of the French Colonial Group Type: Obock (Gold) 2018 –2019 Program Robert P. Odenweller- “New Zealand Air Mails: 1898– Submitted by Edward J. Grabowski and Robert Loeffler 1935” (Large Gold) Co-Chairmen, Program Committee Stephen Reinhard - “The United States Lindbergh Booklet Pane” (Large Gold) January 24, 2019 – Members’ Show & Tell [cont . on page 2] February 28, 2019 – “Philately & International Mail Order Fraud – The New York Institute of Science”. By Edward J. Grabowski Table of contents March 2, 2019 – Westfield Stamp Show Upcoming Meetings . .1 March 28, 2019 – “The Union of South Africa: The 2018–2019 Program . .1 Darstadt Trials of 1929”.