Connectivity Reflects Coding: a Model of Voltage-‐Based Spike-‐ Timing-‐Dependent-‐P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neuronal Dynamics

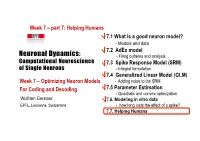

Week 7 – part 7: Helping Humans 7.1 What is a good neuron model? - Models and data 7.2 AdEx model Neuronal Dynamics: - Firing patterns and analysis Computational Neuroscience 7.3 Spike Response Model (SRM) of Single Neurons - Integral formulation 7.4 Generalized Linear Model (GLM) Week 7 – Optimizing Neuron Models - Adding noise to the SRM For Coding and Decoding 7.5 Parameter Estimation - Quadratic and convex optimization Wulfram Gerstner 7.6. Modeling in vitro data EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland - how long lasts the effect of a spike? 7.7. Helping Humans Week 7 – part 7: Helping Humans 7.1 What is a good neuron model? - Models and data 7.2 AdEx model - Firing patterns and analysis 7.3 Spike Response Model (SRM) - Integral formulation 7.4 Generalized Linear Model (GLM) - Adding noise to the SRM 7.5 Parameter Estimation - Quadratic and convex optimization 7.6. Modeling in vitro data - how long lasts the effect of a spike? 7.7. Helping Humans Neuronal Dynamics – Review: Models and Data -Predict spike times -Predict subthreshold voltage -Easy to interpret (not a ‘black box’) -Variety of phenomena -Systematic: ‘optimize’ parameters BUT so far limited to in vitro Neuronal Dynamics – 7.7 Systems neuroscience, in vivo Now: extracellular recordings visual cortex A) Predict spike times, given stimulus B) Predict subthreshold voltage C) Easy to interpret (not a ‘black box’) Model of ‘Encoding’ D) Flexible enough to account for a variety of phenomena E) Systematic procedure to ‘optimize’ parameters Neuronal Dynamics – 7.7 Estimation of receptive fields Estimation of spatial (and temporal) receptive fields ut() k I u LNP =+∑ kKk− rest firing intensity ρϑ()tfutt= ( ()− ()) Neuronal Dynamics – 7.7 Estimation of Receptive Fields visual LNP = stimulus Linear-Nonlinear-Poisson Special case of GLM= Generalized Linear Model GLM for prediction of retinal ganglion ON cell activity Pillow et al. -

Hebbian Learning and Spiking Neurons

PHYSICAL REVIEW E VOLUME 59, NUMBER 4 APRIL 1999 Hebbian learning and spiking neurons Richard Kempter* Physik Department, Technische Universita¨tMu¨nchen, D-85747 Garching bei Mu¨nchen, Germany Wulfram Gerstner† Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Center of Neuromimetic Systems, EPFL-DI, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland J. Leo van Hemmen‡ Physik Department, Technische Universita¨tMu¨nchen, D-85747 Garching bei Mu¨nchen, Germany ~Received 6 August 1998; revised manuscript received 23 November 1998! A correlation-based ~‘‘Hebbian’’! learning rule at a spike level with millisecond resolution is formulated, mathematically analyzed, and compared with learning in a firing-rate description. The relative timing of presynaptic and postsynaptic spikes influences synaptic weights via an asymmetric ‘‘learning window.’’ A differential equation for the learning dynamics is derived under the assumption that the time scales of learning and neuronal spike dynamics can be separated. The differential equation is solved for a Poissonian neuron model with stochastic spike arrival. It is shown that correlations between input and output spikes tend to stabilize structure formation. With an appropriate choice of parameters, learning leads to an intrinsic normal- ization of the average weight and the output firing rate. Noise generates diffusion-like spreading of synaptic weights. @S1063-651X~99!02804-4# PACS number~s!: 87.19.La, 87.19.La, 05.65.1b, 87.18.Sn I. INTRODUCTION In contrast to the standard rate models of Hebbian learn- ing, we introduce and analyze a learning rule where synaptic Correlation-based or ‘‘Hebbian’’ learning @1# is thought modifications are driven by the temporal correlations be- to be an important mechanism for the tuning of neuronal tween presynaptic and postsynaptic spikes. -

Neural Coding and Integrate-And-Fire Model

motor Introduction to computationalneuroscience. cortex Doctoral school Oct-Nov 2006 association visual cortex cortex to motor Wulfram Gerstner output http://diwww.epfl.ch/w3mantra/ Computational Neuroscience 10 000 neurons Signal: 3 km wires action potential (spike) 1mm behavior behavior action potential neurons signals computational model molecules ion channels Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, EPFL Laboratory of Computational Neuroscience, LCN, CH 1015 Lausanne Hodgkin-Huxley type models Integrate-and-fire type models Spike emission j i u i J Spike reception -70mV action potential Na+ K+ -spikes are events Ca2+ -threshold Ions/proteins -spike/reset/refractoriness 1 Models of synaptic Plasticity Computational Neuroscience pre post i Synapse j behavior Neurons synapses computational model molecules ion channels Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, EPFL Laboratory of Computational Neuroscience, LCN, CH 1015 Lausanne Introduction to computationalneuroscience Background: What is brain-style computation? Lecture 1: Passive membrane and Integrate-and-Fire model Brain Computer Lecture 2: Hodgkin-Huxley models (detailed models) Lecture 3: Two-dimensional models (FitzHugh Nagumo) Lecture 4: synaptic plasticity Lecture 5: noise, network dynamics, associative memory Wulfram Gerstner http://diwww.epfl.ch/w3mantra/ Systems for computing and information processing Systems for computing and information processing Brain Computer Brain Computer memory Tasks: CPU slow Mathematical fast æ7p ö input 5cosç ÷ è 5 ø Distributed architecture -

Eligibility Traces and Three-Factor Rules of Synaptic Plasticity

Technische Universität München ENB Elite Master Program Neuroengineering (MSNE) Invited Presentation Prof. Dr. Wulfram Gerstner Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) Eligibility traces and three-factor rules of synaptic plasticity Abstract: Hebbian plasticity combines two factors: presynaptic activity must occur together with some postsynaptic variable (spikes, voltage deflection, calcium elevation ...). In three-factor learning rules the combi- nation of the two Hebbian factors is not sufficient, but leaves a trace at the synapses (eligibility trace) which decays over a few seconds; only if a third factor (neuromodulator signal) is present, either simultaneously or within a short a delay, the actual change of the synapse via long-term plasticity is triggered. After a review of classic theories and recent evidence of plasticity traces from plasticity experiments in rodents, I will discuss two studies from my own lab: the first one is a modeling study of reward-based learning with spiking neurons using an actor-critic architecture; the second one is a joint theory-experimental study showing evidence for eligibility traces in human behavior and pupillometry. Extensions from reward-based learning to surprise-based learning will be indicated. Biography: Wulfram Gerstner is Director of the Laboratory of Computational Neuroscience LCN at the EPFL. He studied physics at the universities of Tubingen and Munich and received a PhD from the Technical University of Munich. His re- search in computational neuroscience concentrates on models of spiking neurons and spike-timing dependent plasticity, on the problem of neuronal coding in single neurons and populations, as well as on the role of spatial representation for naviga- tion of rat-like autonomous agents. -

Burst-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity Can Coordinate Learning in Hierarchical Circuits

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.30.015511; this version posted September 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 2 Burst-dependent synaptic plasticity can coordinate learning in 3 hierarchical circuits 4 1 2,3 4 5,6,7,8 5 Alexandre Payeur • Jordan Guerguiev • Friedemann Zenke Blake A. Richards ⇤• and Richard 1,9, 6 Naud ⇤• 7 1 uOttawa Brain and Mind Institute, Centre for Neural Dynamics, Department of 8 Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada 9 2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Toronto Scarborough, Toronto, ON, 10 Canada 11 3 Department of Cell and Systems Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 12 4 Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, Basel, Switzerland 13 5 Mila, Montr´eal, QC, Canada 14 6 Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, McGill University, Montr´eal, QC, Canada 15 7 School of Computer Science, McGill University, Montr´eal, QC, Canada 16 8 Learning in Machines and Brains Program, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, 17 Toronto, ON, Canada 18 9 Department of Physics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada 19 Corresponding authors, email: [email protected], [email protected] ⇤ 20 Equal contributions • 21 Abstract 22 Synaptic plasticity is believed to be a key physiological mechanism for learning. It is well-established that 23 it depends on pre and postsynaptic activity. -

Spiking Neuron Models Single Neurons, Populations, Plasticity

Spiking Neuron Models Single Neurons, Populations, Plasticity Wulfram Gerstner and Werner M. Kistler Cambridge University Press, 2002 2 Preface The task of understanding the principles of information processing in the brain poses, apart from numerous experimental questions, challenging theoretical problems on all levels from molecules to behavior. This books concentrates on modeling approaches on the level of neurons and small populations of neurons, since we think that this is an appropriate level to adress fundamental questions of neuronal coding, signal trans- mission, or synaptic plasticity. In this text we concentrate on theoretical concepts and phenomenological models derived from them. We think of a neuron primarily as a dynamic element that emits output pulses whenever the excitation exceeds some threshold. The resulting sequence of pulses or ‘spikes’ contains all the information that is transmitted from one neuron to the next. In order to understand signal transmission and signal processing in neuronal systems, we need an understanding of their basic elements, i.e., the neurons, which is the topic of part I. New phenomena emerge when several neurons are coupled. Part II introduces network concepts, in particular pattern formation, collective excitations, and rapid signal transmission between neuronal pop- ulations. Learning concepts presented in Part III are based on spike-time dependent synaptic plasticity. We wrote this book as an introduction to spiking neuron models for advanced undergraduate or graduate students. It can be used either as the main text for a course that focuses on neuronal dynamics; or as part of a larger course in Computational Neuroscience, theoretical biology, neuronal modeling, biophysics, or neural networks. -

Optimal Stimulation Protocol in a Bistable Synaptic Consolidation Model

Optimal stimulation protocol in a bistable synaptic consolidation model Chiara Gastaldi, Samuel P. Muscinelli and Wulfram Gerstner École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Abstract Consolidation of synaptic changes in response to neural activity is thought to be fundamental for memory maintenance over a timescale of hours. In experiments, synaptic consolidation can be induced by repeatedly stimulating presynaptic neurons. However, the effective- ness of such protocols depends crucially on the repetition frequency of the stimulations and the mechanisms that cause this complex de- pendence are unknown. Here we propose a simple mathematical model that allows us to systematically study the interaction between the stimulation protocol and synaptic consolidation. We show the ex- istence of optimal stimulation protocols for our model and, similarly to LTP experiments, the repetition frequency of the stimulation plays a crucial role in achieving consolidation. Our results show that the complex dependence of LTP on the stimulation frequency emerges naturally from a model which satisfies only minimal bistability re- quirements. 1 Introduction Synaptic plasticity, i.e. the modification of the synaptic efficacies due to neural activity, is considered the neural correlate of learning [1–5]. It in- volves several interacting biochemical mechanisms, which act on multiple time scales. The induction protocols for short-term plasticity (STP, on the order of hundreds of milliseconds) [6] and for the early phase of long-term potentiation or depression (LTP or LTD, on the order of minutes to hours) are well established [7–11]. On the other hand, various experiments have arXiv:1805.10116v1 [q-bio.NC] 25 May 2018 shown that, on the timescale of hours, the evolution of synaptic effica- cies depends in a complex way on the stimulation protocol [12–15]. -

Neuronal Dynamics: from Single Neurons to Networks and Models of Cognition Wulfram Gerstner, Werner M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06083-8 - Neuronal Dynamics: From Single Neurons to Networks and Models of Cognition Wulfram Gerstner, Werner M. Kistler, Richard Naud and Liam Paninski Frontmatter More information NEURONAL DYNAMICS What happens in our brain when we make a decision? What triggers a neuron to send out a signal? What is the neural code? This textbook for advanced undergraduate and beginning graduate students provides a thorough and up-to-date introduction to the fields of computational and theoretical neuro- science. It covers classical topics, including the Hodgkin–Huxley equations and Hopfield model, as well as modern developments in the field such as Generalized Linear Models and decision theory. Concepts are introduced using clear step-by-step explanations suitable for readers with only a basic knowledge of differential equations and probabilities, and richly illustrated by figures and worked-out examples. End-of-chapter summaries and classroom-tested exercises make the book ideal for courses or for self-study. The authors also give pointers to the literature and an extensive bibliography, which will prove invaluable to readers interested in further study. Wulfram Gerstner is Director of the Laboratory of Computational Neuroscience and a Professor of Life Sciences and Computer Science at the Ecole´ Polytechnique Fed´ erale´ de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland. He studied physics in T¨ubingen and Munich and holds a PhD from the Technical University of Munich. His research in computational neuroscience concentrates on models of spiking neurons and synaptic plasticity. He teaches computa- tional neuroscience to physicists, computer scientists, mathematicians, and life scientists. He is co-author of Spiking Neuron Models (Cambridge University Press, 2002). -

Voltage-Based Inhibitory Synaptic Plasticity: Network Regulation, Diversity, and Flexibility

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.08.416263; this version posted December 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Voltage-based inhibitory synaptic plasticity: network regulation, diversity, and flexibility Victor Pedrosa1;∗, Claudia Clopath1;∗ 1Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College London ∗Corresponding authors: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Neural networks are highly heterogeneous while homeostatic mechanisms ensure that this heterogeneity is kept within a physiologically safe range. One of such homeostatic mechanisms, inhibitory synaptic plasticity, has been observed across different brain regions. Computationally, however, inhibitory synaptic plasticity models often lead to a strong suppression of neuronal diversity. Here, we propose a model of inhibitory synaptic plasticity in which synaptic updates depend on presynaptic spike arrival and postsynaptic membrane voltage. Our plasticity rule regulates the network activity by setting a target value for the postsynaptic membrane potential over a long timescale. In a feedforward network, we show that our voltage-dependent inhibitory synaptic plasticity (vISP) model regulates the excitatory/inhibitory ratio while allowing for a broad range of postsynaptic firing rates and thus network diversity. In a feedforward network in which excitatory and inhibitory neurons receive correlated input, our plasticity model allows for the development of co-tuned excitation and inhibition, in agreement with recordings in rat auditory cortex. In recurrent networks, our model supports memory formation and retrieval while allowing for the development of heterogeneous neuronal activity. -

Deep Learning with Spike-Assisted Contextual Information Extraction

ScieNet: Deep Learning with Spike-assisted Contextual Information Extraction Xueyuan She Yun Long Daehyun Kim Saibal Mukhopadhyay Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia 30332 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Deep neural networks (DNNs) provide high image classification accuracy, but experience significant performance degradation when perturbation from various sources are present in the input. The lack of resilience to input perturbations makes DNN less reliable for systems interacting with physical world such as autonomous vehicles, robotics, to name a few, where imperfect input is the nor- mal condition. We present a hybrid deep network architecture with spike-assisted contextual information extraction (ScieNet). ScieNet integrates unsupervised learn- ing using spiking neural network (SNN) for unsupervised contextual information extraction with a back-end DNN trained for classification. The integrated network demonstrates high resilience to input perturbations without relying on prior train- ing on perturbed inputs. We demonstrate ScieNet with different back-end DNNs for image classification using CIFAR dataset considering stochastic (noise) and structured (rain) input perturbations. Experimental results demonstrate significant improvement in accuracy on noisy and rainy images without prior training, while maintaining state-of-the-art accuracy on clean images. 1 Introduction Statistical machine learning using deep neural network (DNN) has demonstrated high classification accuracy on complex inputs in many application domains. Motivated by the tremendous success of DNNs in computer vision [1, 2, 3] there is a growing interest in employing DNNs in autonomous systems interacting with physical worlds, such as unmanned vehicles and robotics. However, these applications require DNNs to operate on “novel” conditions with perturbed inputs. -

Neuronal Dynamics

Week 2 – part 5: Detailed Biophysical Models 2.1 Biophysics of neurons Neuronal Dynamics: - Overview 2.2 Reversal potential Computational Neuroscience - Nernst equation of Single Neurons 2.3 Hodgin-Huxley Model 2.4 Threshold in the Week 2 – Biophysical modeling: Hodgkin-Huxley Model The Hodgkin-Huxley model - where is the firing threshold? Wulfram Gerstner 2.5. Detailed biophysical models - the zoo of ion channels EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland Neuronal Dynamics – 2.5 Biophysical models inside Ka Na outside Ion channels Ion pump α β Neuronal Dynamics – 2.5 Ion channels Na+ K+ Steps: Different number Ca2+ of channels Ions/proteins Na+ channel from rat heart (Patlak and Ortiz 1985) A traces from a patch containing several channels. Bottom: average gives current time course. B. Opening times of single channel events Neuronal Dynamics – 2.5 Biophysical models inside Ka There are about 200 identified ion channels Na outside Ion channels Ion pump http://channelpedia.epfl.ch/ How can we know α which ones are present β in a given neuron? Ion Channels investigated in the study of! α Toledo-Rodriguez, …, Markram (2004) Voltage Activated K+ Channels! Kv α β Kv1 Kv2 Kv3 Kv4 Kv5 Kv6 Kv8 Kv9 β Kvβ KChIP + + Kvβ1 Kvβ2 Kvβ3 Kv1.1 Kv1.2 Kv1.3 Kv1.4 Kv1.5 Kv1.6 Kv2.1 Kv2.2 Kv3.1 Kv3.2 Kv3.3 Kv3.4 Kv4.1 Kv4.2 Kv4.3 KChIP1 KChIP2 KChIP3 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! CB PV CR NPY VIP Dyn SP CRH SOM CCK pENK CGRP I C g gl Na gKv1 g schematic mRNA! Kv3 Expression profile! Model of a hypothetical neuron I inside Ka C g gl Na gKv1 gKv3 Na outside Ion channels Ion pump -

Hebbian Plasticity Requires Compensatory Processes on Multiple Timescales

Hebbian plasticity requires compensatory processes on multiple timescales 1; 2 Friedemann Zenke ∗and Wulfram Gerstner January 16, 2017 1) Dept. of Applied Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA orcid.org/0000-0003-1883-644X 2) Brain Mind Institute, School of Life Sciences and School of Computer and Communication Sciences, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne EPFL, Switzerland orcid.org/0000-0002-4344-2189 This article is published as: Zenke, F., and Gerstner, W. (2017). Hebbian plasticity requires compensatory processes on multiple timescales. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160259. DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0259 http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/372/1715/20160259 Abstract We review a body of theoretical and experimental research on Hebbian and homeostatic plasticity, starting from a puzzling observation: While homeostasis of synapses found in exper- iments is a slow compensatory process, most mathematical models of synaptic plasticity use rapid compensatory processes. Even worse, with the slow homeostatic plasticity reported in experiments, simulations of existing plasticity models cannot maintain network stability unless further control mechanisms are implemented. To solve this paradox, we suggest that in ad- dition to slow forms of homeostatic plasticity there are rapid compensatory processes which stabilize synaptic plasticity on short timescales. These rapid processes may include heterosy- naptic depression triggered by episodes of high postsynaptic firing rate. While slower forms of homeostatic plasticity are not sufficient to stabilize Hebbian plasticity, they are important for fine-tuning neural circuits. Taken together we suggest that learning and memory rely on an intricate interplay of diverse plasticity mechanisms on different timescales which jointly ensure stability and plasticity of neural circuits.