The Case of Weaving Districts in the Meiji Japan1 Tomok

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Certified Facilities (Cooking)

List of certified facilities (Cooking) Prefectures Name of Facility Category Municipalities name Location name Kasumigaseki restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Tokyo-club Building,3-2-6,Kasumigaseki,Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Sakura terrace,Iidabashi Grand Bloom,2-10- ALOHA TABLE iidabashi restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 2,Fujimi,Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku banquet kitchen The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 24th floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Peter The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Boutique & Café First basement, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Hei Fung Terrace The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Lobby 1-1-1,Uchisaiwai-cho,Chiyoda-ku TORAYA Imperial Hotel Store restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (Imperial Hotel of Tokyo,Main Building,Basement floor) mihashi First basement, First Avenu Tokyo Station,1-9-1 marunouchi, restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (First Avenu Tokyo Station Store) Chiyoda-ku PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Hot hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku Kitchen,Cold Kitchen) PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Preparation) hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku LE PORC DE VERSAILLES restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First~3rd floor, Florence Kudan, 1-2-7, Kudankita, Chiyoda-ku Kudanshita 8th floor, Yodobashi Akiba Building, 1-1, Kanda-hanaoka-cho, Grand Breton Café -

Evaluation of the Effect of Regional Pollutants and Residual Ozone on Ozone Concentrations in the Morning in the Inland of the Kanto Region

Asian Journal of Atmospheric Environment Vol. 9-1, pp. 1-11, March 2015 Ozone Concentration in the Morning in InlandISSN(Online) Kanto Region 2287-11601 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5572/ajae.2015.9.1.001 ISSN(Print) 1976-6912 Evaluation of the Effect of Regional Pollutants and Residual Ozone on Ozone Concentrations in the Morning in the Inland of the Kanto Region Yusuke Kiriyama*, Hikari Shimadera1), Syuichi Itahashi2), Hiroshi Hayami2) and Kazuhiko Miura Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo, Japan 1)Center for Environmental Innovation Design for Sustainability, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan 2)Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Abiko, Japan *Corresponding author. Tel: +81-3-5228-8215, E-mail: [email protected] of stratospheric ozone, and the effect of domestic pol- ABSTRACT lutant sources. Focusing on the Kanto region in Japan (the area in and around metropolitan Tokyo on the Increasing ozone concentrations are observed over Pacific coast of Japan) during summer, seasonal wind Japan from year to year. One cause of high ozone from the Pacific Ocean dominates wind patterns and concentration in the Kanto region, which includes blocks air masses approaching from inland. Pocha- areas inland from large coastal cities such as metro- nart et al. (2002) showed reduced inland air mass to politan Tokyo, is the transportation of precursors by sea breezes. However, high ozone concentrations the Pacific coast of Japan in summer relative to other are also observed in the morning, before sea breezes seasons by monitoring pollutants at remote islands approach inland areas. In this point, there would be and performing backward trajectory analyses. -

Structure of the Corporate Principles

Corporate Vision Structure of the Corporate Principles To create the affluent society The Corporate principles systematizes the origin of the behavior of companies and employees environment and comfort are in harmony, which Sanden should realize as “Global Excellent Companies”. we will continue to open up a new era Founding Spirit and become a company all the people trusts. Management Principles Having the founding spirit of Corporate Philosophy ‘Let us Develop with Wisdom and Prosper in Harmony’ Corporate Vision as a basic philosophy, Sanden has continually been building Management Policies the corporate culture of challenge and innovation since its establishment in 1943. Mid-Term Plan,Execution Plan We believe our mission is to solve the social issues of the respective countries by providing new value STQM <STQM SANDEN WAY> and achieve industrial and economic development, people’s health, and enriched society especially in the ‘Integrated Thermal Management’ field. Founding Spirit This means that we should use our intelligence in combining our developmental and pioneering abilities to win prosperity for us all. Let us Develop with Wisdom and Prosper in Harmony Management Principles Our management Principles have been the cornerstone of our employees’activities since the company’s founding. ・Satisfy our customer's needs with high quality products. ・Contribute to the social and cultural improvement of community through business activity. The extensive mountains with lush greenery. The blue clear sky. ・Build a company of which all are proud, through the effort of self-motivated employees. A blue flash streaking far in the distance through such a beautiful scenery represents the Sanden-created 'comfort' that opens up a new era forever and ever. -

![List of Signatories[PDF:57KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0497/list-of-signatories-pdf-57kb-1790497.webp)

List of Signatories[PDF:57KB]

List of signatories (listed in Japanese alphabetical order) Total approximate Company Service prefecture Service area(s) number of households in service area(s)*1 1 Ueda Gas Co., Ltd. Nagano Prefecture Ueda City 30,000 Tomi City 2 Nagano toshi Gas Nagano Prefecture Nakano City 96,000 Co., Ltd. Suzaka City Nagano City Chikuma City Ueda City Tomi City Komoro City Saku City Yamanouchi Town Obuse Town Miyota Town 3 Honjo Gas Co., Ltd. Saitama Prefecture Honjo City 14,000 Kodama District Kamisato City/Misato City (excluding some sections in both cities) 4 Ashikaga Gas Co., Tochigi Prefecture Ashikaga City 17,000 Ltd. Gunma Prefecture Ota City 5 Isesaki Gas Co., Ltd. Gunma Prefecture Isesaki City 12,000 6 Iruma Gas Co., Ltd. Saitama Prefecture Iruma City 18,000 Sections of Hanno City Sections of Sayama City 7 Ome Gas Co., Ltd. Tokyo Metropolis Ome City 22,000 8 Ota toshi Gas Co., Gunma Prefecture Sections of Ota City 13,000 Ltd. *2 Oizumi Town 9 Kiryu Gas Co., Ltd. Gunma Prefecture Kiryu City 26,000 Sections of Midori City Sections of Ohta City 10 Saitama Gas Co., Saitama Prefecture Sections of Fukaya City 7,000 Ltd. 11 Sano Gas Co., Ltd. Tochigi Prefecture Sano City 9,000 12 Suwa Gas Co., Ltd. Nagano Prefecture Okaya City 20,000 Suwa City Sections of Chino City Suwa District Shimosuwa Town 13 Seibu Gas Co., Ltd. Saitama Prefecture Sections of Hanno City 12,000 Sections of Hidaka City 14 Hidaka Toshi Gas Saitama Prefecture Sections of Hidaka City 7,000 Co., Ltd. -

Hogushi and Heiyo: Methods of Creating Painterly Images in Woven Textiles

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1998 Hogushi and Heiyo: Methods of Creating Painterly Images in Woven Textiles Kazuo Mutoh Kiryu Orijuku Textile Archive and Study Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Mutoh, Kazuo, "Hogushi and Heiyo: Methods of Creating Painterly Images in Woven Textiles" (1998). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 196. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Panel Title: From Kitsch to Art Moderne: Popular Textiles for Women in the First Half of Twentieth-Century Japan by Arai, Mutoh, and Wada (for introduction to panel, see paper by Wada) Hogushi and Heiyo: Methods of Creating Painterly Images in Woven Textiles by Kazuo Mutoh Kiryu Orijuku Textile Archive and Study Center Proto-Meisen The term meisen generally refers to plain-weave silk cloth patterned with woven (not printed) stripes or kasuri and made into kimono, haori, and nen 'neko (literally 'jacket sleeper, " a padded coat worn during the autumn and winter months for carrying babies on the back). In the first halfofthe twentieth century, almost all Japanese women were familiar with meisen as ordinary, everyday wear for the upper and middle classes and as dress-up kimono for work ing-class and country women. -

March 20, 2013 News Release for Immediate Release Sign Up

March 20, 2013 News Release For Immediate Release Sign Up Now for Fall Tour of Isesaki, Japan The Springfield Sister Cities Association invites residents to join a 16-person delegation visiting Springfield's Sister City, Isesaki, Japan, Oct. 29 - Nov. 7, 2013. The trip includes three days in Isesaki and five days in the cities of Kyoto, Nara and Tokyo. Springfield Sister Cities Association coordinator Cindy Jobe says the trip is geared for community-minded residents interested in international travel, participating in cultural exchanges and building friendships. "It's a unique way to travel and tour," said Jobe. "You're traveling with friends and you have friends waiting there for you when you arrive. It's a much more personal experience than a typical tour. That's our mission: 'Peace through People.'" Highlights include tours of historic temples, shrines, gardens, castles and museums; shopping; an official welcome hosted by the City of Isesaki and the option to stay with an Isesaki host family. The trip cost is $2,500 (plus airfare) per person, based on double-occupancy, and includes all lodging, ground travel and high-speed train fare within Japan, and most meals. Accommodations are at traditional Japanese inns called ryoken. Participants may book their own flights or book through Springfield Sister Cities Association. Space is limited to 16 travelers. A $500 deposit is required by April 15. Information about the Springfield Sister Cities Association and Springfield's 28-year relationships with Isesaki is at peacethroughpeople.org . For more information, call the Springfield Sister Cities Association at 417-864-1341. -

Register of Medical Institutions Issuing COVID-19 Testing

Register of Medical Institutions Issuing COVID-19 Testing Certificates as of September 20th, 2021 【About Antigen test kit (qualitative antigen test)】 ・In Japan, PCR Test including LAMP Method and Quantitative Antigen Test are permitted for asymptomatic patient as appropriate test method, but Antigen test kit (qualitative antigen test) are not permitted. ・At the request of the destination, Antigen test kit (qualitative antigen test) is used for asymptomatic patient, and if the test result is positive, PCR Test or other appropriate test method may be performed based on doctor's judgement. ※Permitted test method in Japan are highlighted in light blue at the table below. ※Reference: Guidelines for COVID-19 Pathogen Test Basic Information of Medical Institution Inspection Information Contact Address Testing Methods for Issuing a Certificate Information TeCOT PCR Testing PCR Testing Antigen Testing Antigen Testing No Reservation LAMP Method Other Methods Real-Time Method Non-Real-Time Method Simple Kit Quantitative Availability Medical Institution Name Phone Prefecture Municipality Street Address Nasopharynx Saliva Nasopharynx Saliva Nasopharynx Saliva Nasopharynx Saliva Nasopharynx Saliva Nasopharynx Saliva Number Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Min. Req. Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Availability Time Time Time Time Time Time Time Time Time Time Time Time -

Yoshida Shigeki 2020

Shigeki Yoshida 1963 Born in Ibaragi, Japan 1987 BA, Wako University, Tokyo, Japan 2003-04 Exchange Study, Berlin University of the Arts, Berlin, Germany 2005 MFA, Hunter College, CUNY Currently lives and works in New York City Selected Solo Exhibitions 2014 Shinjuku Takashimaya, Tokyo, Japan 2012 Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo Yace Gallery, Long Island, NY, USA 2008 Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan 2007 Safe-T-Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, USA Selected Group Exhibitions 2015 micro salon, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan SHADOW-LANDS: THE SUFFERING IMAGE, Deakin University, Melbourne, Aus- tralia Una Historia Vintage, a flat on Calle Alcalá, Madrid, Spain 2014 micro salon, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan 2013 micro salon, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan 2012 micro salon, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan 2011 micro salon, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan 2010 micro salon 60, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan Tokyo Gallery 60th Anniversary Exhibition, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan 2009 The Photo-Graph of Nonexistent, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan The Photo Review – Best of Show, Gallery 1401, The University of The Arts, Philadelphia, PA, USA 2007 A Certain Slant of Light, Rush Corridor Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, USA Barely There, Hewitt Gallery of Art at Marymount Manhattan College, New York, NY, USA Darkroom Residents Exhibition, The Camera Club of New York, NY, USA OEDIFICE COMPLEX, The Camera Club of New York, NY, USA S-T-G V, Safe-T-Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, USA Susan Eley’s October Show, Susan Eley Fine Art, New York, NY, USA -

Business Partnership Agreement Between Isesaki Gas and TOKAI Holdings - New Collaboration Model of Community-Based Companies

August 26, 2019 To whom it may concern TOKAI Holdings Corporation Katsuhiko Tokita, President & CEO (Code No. 3167 Tokyo Stock Exchange First Section) Isesaki Gas Co., Ltd. Yoshifumi Tajima, President Business Partnership Agreement between Isesaki Gas and TOKAI Holdings - New collaboration model of community-based companies - Isesaki Gas Co., Ltd. (Head Office: Isesaki City, Gunma Prefecture, Japan; "Isesaki Gas") and TOKAI Holdings Corporation (Head Office: Aoi-ku, Shizuoka City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan; “TOKAI Holdings”) announced today that they have reached an agreement and entered into a business partnership agreement to collaborate and cooperate to further develop their gas businesses and become infrastructure service providers that contribute more to the lives of local communities and their residents. 1. Background and purpose of the business partnership Isesaki Gas, since its foundation in 1963, has supported the residential and industrial use of energy in Isesaki City through the city gas business as its main business. As an important lifeline provider supporting the local community, Isesaki Gas strives not only to secure a stable supply of energy and ensure security, but also to contribute to the affluent and comfortable lifestyles of the residents of Isesaki City. At the same time, Isesaki Gas plays a major role in promoting local industries by supplying energy to new industrial parks that Isesaki City is actively promoting. As such, Isesaki Gas has built a strong foundation of trust as an indispensable business in Isesaki City. The city of Isesaki is also blessed with convenient access to Tokyo and other areas within and outside the prefecture because it is connected to the Kan-etsu Expressway and the Tohoku Expressway through the Kita-Kanto Expressway. -

ORIX JREIT Announces Acquisition of Two Properties: Koshigaya Logistics Center and Shinjuku 5-Chome Building (Provisional Name)

[Provisional Translation Only] This English translation of the original Japanese document is provided solely for information purposes. Should there be any discrepancies between this translation and the Japanese original, the latter shall prevail. For Immediate Release March 27, 2006 ORIX JREIT Inc. (TSE: 8954) Hiroshi Ichikawa Executive Director Inquiries: ORIX Asset Management Corporation Mitsuo Sato Director, Corporate Executive Vice President Tel: +81 3 3435 3285 ORIX JREIT Announces Acquisition of Two Properties: Koshigaya Logistics Center and Shinjuku 5-chome Building (provisional name) TOKYO, March 27, 2006-ORIX JREIT Inc. (“OJR”) announced today that it has decided to purchase the Koshigaya Logistics Center and the Shinjuku 5-chome Building (“property” below). 1. Acquisition summary Shinjuku 5-chome Building Property name Koshigaya Logistics Center (provisional name, under construction) Asset to be acquired Property Property Acquisition price ¥ 4,000,000,000 ¥ 4,500,000,000 (excluding consumption tax on the building) (excluding consumption tax on the building) Expected acquisition date April 28, 2006 April 26, 2007 Current owner / Seller ORIX Corporation ORIX Real Estate Corporation Anticipated funding method Loan proceeds Loan proceeds Approximately 5% down on execution Payment terms 100% on transfer of contract and 95% on transfer Others Office Property type (Warehouses/distribution facilities) (Project under development) ・OJR may conduct necessary due diligence on completion ・Completion is condition precedent to transfer of property Terms of acquisition ― (related to project development) ・Settlement of price to be on or after completion ・Presence or absence of tenants shall not affect the sale price 1/12 2. Acquisition based on new OJR WAY investment principles The acquisition of both properties is based on the new OJR WAY investment principles. -

From Narita International Airport from Haneda Airport Transportation Guide There Sa Never-Ending List of Fun, Memorable E

▼ Shima Onsen ▶ Mount Tanigawa ◀ Ozegahara Shima is celebrated as “the spring of Straddling the border Oze is one of the precious What is the GuGutto GUNMA Tourism Campaign? beauties.” This onsen town is full of simple, between Gunma and few remaining nostalgic charm. A famous event known as Niigata prefectures, this is The GuGutto GUNMA Tourism Campaign is a public-relations high-altitude wetlands. It's the “Chochin (Paper Lantern) Walk” is held counted as one of Japan’s a world rich in the variety program designed to spread the word about Gunma’s many here, in which people walk through the hundred most famous of rare living things, attractions, showing people all the excitement there is to town swinging paper lanterns in one hand. mountains. Mount including mountain plants discover in Gunma. Tanigawa’s rock walls, and insects. The grandeur The campaign is packed with new experiences and a variety of including Ichinokurasawa, and refreshing atmosphere are among the three most are a pleasure to witness. events. Come and taste the charms of Gunma! notable rock formations in Japan, and are considered Here’s what’s behind the theme, “GuGutto GUNMA ‒ Discover to be the Mecca of exciting new experiences.”: Japanese rock climbing. From trekking to full-blown We would like everyone to get mountain climbing, there excited with visiting attractive are many ways to enjoy spots and events in Gunma and Mount Tanigawa. ▼ Kusatsu Onsen have memorable experiences that Kusatsu is one of Japan’s most renowned get to your heart. onsen resorts, boasting the highest amount of natural hot water discharge of Oze any onsen resorts in the country. -

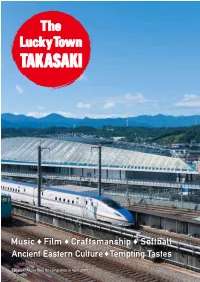

One of a Kind the Oldest Sake Brewery in Gunma Clear and Pure

Niig a ta Kanazawa Takasaki, Connecting the Kanto Utsunomiya Nagano Takasaki Hitachinaka and Shin-etsu Regions Karuizawa Mito Tokyo With a well-developed transportation network providing great accessibility, Yokohama Takasaki is a pivotal city in the Joshin-etsu and northern Kanto regions. Boasting first class infrastructure, a rich urban culture Direct access to Tokyo from Takasaki, and the largest population in Gunma Prefecture, the gateway to Gunma Prefecture 50 minutes from Tokyo, Takasaki is a convenient, comfortable and enjoyable place to live or visit. 15 minutes to Karuizawa Outer suburbs are blessed with beautiful nature, Takasaki is 50 minutes by Shinkansen from Tokyo or 60 adorned by the charms of the four seasons. minutes by car from Tokyo’s Nerima Interchange on the Kan-etsu Expressway. Takasaki is a residential area within commuting distance of Tokyo thanks to direct access to major train stations in the capital via the Shonan-Shinjuku and Ueno-Tokyo lines. Located in the center of Honshu, Takasaki is a pivotal point in the inland transportation network, with the Kan-etsu, Kita-Kanto, and Joshin-etsu Expressways, and Joetsu and Hokuriku Shinkansen lines passing through the city. Work was completed on the extension of the Hokuriku Shinkansen line to Kanazawa in March 2015, further improving Takasaki’s convenient location. Takasaki is within easy reach of the internationally-known resort town of Karuizawa. Gunma is also home to the popular hot spring towns of Kusatsu, Ikaho, Minakami and Shima, and Takasaki’s transportation network makes it a base for visiting not only Tomioka Silk Mill but also the many other tourist spots in the prefecture.