Barry University: Its Beginnings by Sister Eileen F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cement May 9, 1992

CEMENT MAY 9, 1992 ·_···:·:~ ... '":' ··,. WSU Branch Campus and Center Ceremonies Commencement-related ceremonies will be held at all WSU branches and centers according to the following schedule: WSU Intercollegiate Center for Nursing 4:00 p.m., Friday, May 8-The Spokane Education Metropolitan Performing Arts Center WSU Seattle Center for Hotel and 7:00 p.m., Thursday, June I I-Pigott Restaurant Administration Auditorium, Seattle University WSU Spokane 4:00 p.m., Friday, May 8-The Spokane Metropolitan Performing Arts Center WSU Tri-Cities 7:00 p.m., Friday, May IS-Richland High School Auditorium, Richland WSU Vancouver 7:00 p.m., Sunday, May IO-Evergreen High School Auditorium, Vancouver COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES NINETY-SIXTH ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT Nine O'Clock Saturday, May Ninth Nineteen Hundred and Ninety-two Pullman, Washington Commencement Recognition Ceremonies will be held following the All-University Commencement Exercises. Time and location can be found immediately preceding the list of degree candidates, by college. ••• 2 COMMENCEMENT 1992 Washington State University, on the occasion of its 96th annual commencement, cordially welcomes all those who have come to the Pullman campus to share in ceremonies honoring the members of the graduating class of 1992. All are encouraged to attend the College and School Commencement Recognition Ceremonies being held throughout the day. To the members of the Class of 1992, the university extends sincere congratulations. Washington State University is dedicated to the preparation of students for productive lives and profes sional careers, to basic and applied research in a variety of areas, and to the dissemination of knowledge. The university consists of seven colleges, a graduate school, an Intercollegiate Center for Nursing Education in Spokane and Yakima, the Center for Hotel and Restaurant Administration in Seattle, and branch campuses in Spokane, the Tri-Cities, and Vancouver. -

Nation's Necroes Convention

Patronize Our Advertis- GOOD CONDUCT WILL ers — Their Advertising ALWAYS GAIN YOU in this paper shows that RESPECT. Watch Your they appreciate your Public trade. Conduct. MISSISSIPPI, AUGUST 1956 PRICE TEN VOLUME XIV—NUMBER 43 JACKSON, SATURDAY, 18, CENtS EYE DEMO. * CONVENTION NATION'S NECROES I w ************ Democratic national Convention now Underway In Chicago Getting Close Of New Orleans Catholic Schools From The Nation’s — Scrutiny Integration■ Negro Postpone j*. M •---* ui new Voters As Politicians Make Archbishop Joseph itummei Well Known Say Civil Rights Police Break-Up Jesse Owens, One Writes Letter To Diocese Civil Rights A Major Issue Orleans Jackson Man Not Top Concern Anti-Negro Mob Of The Nation’s Of Negro Democratic Leaders Playing Announcing Postponement Faced With Of Voters Near Site Of * Greatest Athletes Important Roles At Convention Schools Negro Integration Of Catholic Negro Voters Cite Democratic Natl. To Be Guest Of Chicago, 111., Aug. 15.—(DSN)— Serious The eyes of the nations cit- Charge Pocketbook Issue Negro SCHOOL TO REMAIN LARGELY Kent Bullock izen in all sections of the country Charged Aug. 14.— were focused on the Demo- NEXT YEAR Minneapolis, Minn., Convention AME Youth Meet i being SEGREGATED UNTIL With Attempted Rape The Negro voter, wholly apart from cratic National Convention which the Negro leader, might surprise Mob Meeting At Campbell got under way here Monday largely La., Aug. 12.— Aroused By New Orleans, In Attacking Young the platform committee. He talks for the reason that top political Rummel an- Here Archbishop Joseph much more about his pocketbook Rumor Of Negro College leaders as well as the leading can- last that integra- j White Couple nounced Sunday and his vote than civil rights and Next Week didates have made civil rights a schools of the In tion of Catholic A well known and prominent his vote. -

===~111===D=~=Ce=M=Be=R==~Ii====~

c. c~ ~====~111===D=~=CE=M=BE=R==~II====~ BISHOPS' ANNUAL MEETING NUMBER -Including- A Report of the Proceedings of the November, 1931, Meeting of the Archbishops and Bishops of the United States Digests of the Annual Reports of the Episcopal Chairmen of the National Catholic Welfare Conference The Bishops' Statement on the Unemployment Crisis ADDITIONAL FEATURES Peace: A Summary Text for Individual Study or for Three Discussions at Group or Organization Meetings; Analysis of the Report of the President's Advisory Com mittee on Education; Full Text of the Resolutions Adopted by the Catholic Rural Life Conference; Reports of Recent Meetings of Diocesan and Deanery Units of the N. C. C. w. An Announcement of Importance to All Our Subscribers (See pages 16-17) Subscription Price VOL. XIII, No. 12 Domes tic-$l.00 per year December, 1931 Foreign-$l.25 per year 2 N. C. W. C. REVIEW December, 1931 N. c. W~ C. REVIEW OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WELFARE CONFERENCE N. C. w. C. Administrative ({This organization (the N. C. Purpose of the N. C. W. C. Committee W. C.) is not only useful, but IN THE WORDS OF OUR HOLY FATHER: MOST REV. EDWARD .T. HANNA, D.D. necessary. .. We praise all "Since you (the Bishops) reside in Archbishop of San FranciscQ cities far apart and there are matters who in any way cooperate in this of a higher imp01't demanding your Chairman great work.N-POPE PIUS XI. joint deliberation. • • . it is im perative that by taking counsel together RT. REV. THOMAS F. -

Via Sapientiae Volume 17: 1946-47

DePaul University Via Sapientiae De Andrein Vincentian Journals and Publications 1947 Volume 17: 1946-47 Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Volume 17: 1946-47. https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in De Andrein by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CS rnIc %NVfa Volume 17 Perryville, Missouri, October, 1946 / No. 1 CONFRERES STAFF NEW SEMINARY Faculty Row and Classrooms with Chapel in Distance Pict:res Courtesy Southwest Courier High School Dormitory Student Dining Room His Excellency, Bishop Eugene J. Mc- homa. It is the completion of a hope Conscious of the grave obligation, the Guinness, has entrusted to the care of long cherished by Bishop McGuinness. Community feels honored in the part the Community the new Preparatory His Excellency is well aware of the it is to take in this new project. Seminary that is destined to serve the need of such a Seminary, and is con- Catholic interests of the State of Okla- fident that the advantages of train- At the present the arrangement at the Seminary is only provisional. It homa. Located at Bethany, the in- ing future priests within the Oklahoma consists of about ten small stitution is about five miles from Okla- City-Tulsa Diocese will more than off- units with homa City and is conveniently reach- siet the sacrifices entailed in the in- two larger houses. -

Via Sapientiae Volume 29: 1958-59

DePaul University Via Sapientiae De Andrein Vincentian Journals and Publications 1959 Volume 29: 1958-59 Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Volume 29: 1958-59. https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in De Andrein by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ae -pet" VOLUME 29 PERRYVILLE, MISSOURI OCTOBER, 1958 NUMBER 1 TWO FILIAL VICE-PROVINCES ESTABLISHED - -- -~--- '' On the feast day of our holy foun- der, St. Vincent de Paul, the Very Reverend John Zimmerman, C.M., as- sistant to the Superior General, in- formed us of the division of our Wes- tern Province into one Mother Province and two Filial Vice-Provinces. He also mentioned that the Very Reverend James W. Stakelum, C.M.V., would remain Provincial of the Midwest area, now known as the Mother Province. The Filial Vice-Provinces will each have a Vice-Provincial, Father Maurice J. Hymel for the South and Father James W. Richardson for the Far West. Father Hymel's headquarters will be in New Orleans where he is Pastor of St. Joseph's Church. Father Richardson will continue to reside in California. In a letter sent to the Community houses, Father Stakelum explained that the division of the Province has a twofold purpose. First of all, more at- tention can now be given to the con- freres and the affairs of each house because both of the Vice-P'rovincials will assume the duties of the Provin- cial in their own Vice-Province. -

The Education of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1989 Race Relations and Community Development: The ducE ation of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960. Donald E. Devore Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Devore, Donald E., "Race Relations and Community Development: The ducaE tion of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960." (1989). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4839. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

St. Augustine Statistics

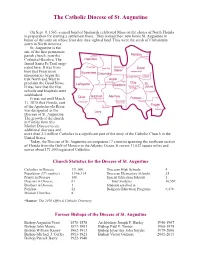

The Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine On Sept. 8, 1565, a small band of Spaniards celebrated Mass on the shores of North Florida in preparation for starting a settlement there. They named their new home St. Augustine in honor of the saint on whose feast day they sighted land. Thus were the seeds of Christianity sown in North America. St. Augustine is the site of the first permanent parish church, now the Cathedral-Basilica. The famed Santa Fe Trail origi- nated here. It was from here that Franciscan missionaries began the trek North and West to proclaim the Good News. It was here that the first schools and hospitals were established. It was not until March 11, 1870 that Florida, east of the Apalachicola River, was designated as the Diocese of St. Augustine. The growth of the church in Florida from this Mother Diocese to six additional dioceses and more than 2.1 million Catholics is a significant part of the story of the Catholic Church in the United States. Today, the Diocese of St. Augustine encompasses 17 counties spanning the northeast section of Florida from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Ocean. It covers 11,032 square miles and serves about 171,000 registered Catholics. Church Statistics for the Diocese of St. Augustine Catholics in Diocese 171,000 Diocesan High Schools 4 Population (17 counties) 1,966,314 Diocesan Elementary Schools 25 Priests in Diocese 148 Special Education Schools 1 Deacons in Diocese 61 Total Students 10,559 Brothers in Diocese 1 Students enrolled in Parishes 52 Religious Education Programs 9,478 Mission Churches 8 *Source: The 2010 Official Catholic Directory Former Bishops of the Diocese of St. -

Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects Summer 2016 Between Third Reich and American Way: Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939 Christian Wilbers College of William and Mary - Arts & Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wilbers, Christian, "Between Third Reich and American Way: Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1499449834. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2JD4P This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Third Reich and American Way: Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939 Christian Arne Wilbers Leer, Germany M.A. University of Münster, Germany, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2016 © Copyright by Christian A. Wilbers 2016 ABSTRACT Historians consider the years between World War I and World War II to be a period of decline for German America. This dissertation complicates that argument by applying a transnational framework to the history of German immigration to the United States, particularly the period between 1919 and 1939. The author argues that contrary to previous accounts of that period, German migrants continued to be invested in the homeland through a variety of public and private relationships that changed the ways in which they thought about themselves as Germans and Americans. -

Guide to the Catholic Maritime Clubs and the National Conference of the Apostleship of the Sea Records CMS.032

Guide to the Catholic Maritime Clubs and the National Conference of the Apostleship of the Sea Records CMS.032 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit January 30, 2015 Center for Migration Studies Guide to the Catholic Maritime Clubs and the National Conference of the Apostleship of the Sea Recor... Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 History of the National Conference of the Apostleship of the Sea.............................................................. 5 History of the Catholic Maritime Clubs in the United States.......................................................................5 History of the Apostleship of the Sea...........................................................................................................6 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 7 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................8 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................9 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................9 Other Finding Aids note..............................................................................................................................10 -

Of 217 11:45:20AM Club Information Report CUS9503 09/01/2021

Run Date: 09/22/2021 Key Club CUS9503 Run Time: 11:53:54AM Club Information Report Page 1 of 217 Class: KCCLUB Districts from H01 to H99 Admin. Start Date 10/01/2020 to 09/30/2021 Club Name State Club ID Sts Club Advisor Pd Date Mbr Cnt Pd Amount Kiwanis Sponsor Club ID Div H01 - Alabama Abbeville Christian Academy AL H90124 Debbie Barnes 12/05/2020 25 175.00 Abbeville K04677 K0106 Abbeville High School AL H87789 Valerie Roberson 07/06/2021 9 63.00 Abbeville K04677 K0106 Addison High School AL H92277 Mrs Brook Beam 02/10/2021 19 133.00 Cullman K00468 K0102 Alabama Christian Academy AL H89446 I Page Clayton 0 Montgomery K00174 K0108 Alabama School Of Mathematics And S AL H88720 Derek V Barry 11/20/2020 31 217.00 Azalea City, Mobile K10440 K0107 Alexandria High School AL H89049 Teralyn Foster 02/12/2021 29 203.00 Anniston K00277 K0104 American Christian Academy AL H94160 I 0 Andalusia High School AL H80592 I Daniel Bulger 0 Andalusia K03084 K0106 Anniston High School AL H92151 I 0 Ashford High School AL H83507 I LuAnn Whitten 0 Dothan K00306 K0106 Auburn High School AL H81645 Audra Welch 02/01/2021 54 378.00 Auburn K01720 K0105 Austin High School AL H90675 Dawn Wimberley 01/26/2021 36 252.00 Decatur K00230 K0101 B.B. Comer Memorial School AL H89769 Gavin McCartney 02/18/2021 18 126.00 Sylacauga K04178 K0104 Baker High School AL H86128 0 Mobile K00139 K0107 Baldwin County High School AL H80951 Sandra Stacey 11/02/2020 34 238.00 Bayside Academy AL H92084 Rochelle Tripp 11/01/2020 67 469.00 Daphne-Spanish Fort K13360 K0107 Beauregard High School AL H91788 I C Scott Fleming 0 Opelika K00241 K0105 Benjamin Russell High School AL H80742 I Mandi Burr 0 Alexander City K02901 K0104 Bessemer Academy AL H90624 I 0 Bob Jones High School AL H86997 I Shari Windsor 0 Booker T. -

American Catholicism, American Politics Reconsidered a State of The

American Catholicism, American Politics Reconsidered A State of the Field Panel Discussion with Timothy Matovina, Eugene McCarraher, Kristy Nabhan-Warren, and Leslie Woodcock Tentler. Moderated by Marie Griffith. March 10, 2016 Umrath Hall R. Marie Griffith: Good afternoon. Welcome to today’s state of the field panel discussion on Catholicism and U.S. Politics, sponsored by the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis. This is an event intended to be in conjunction and in conversation with last week’s public lecture by His Eminence Cardinal Timothy Dolan, Archbishop of New York. I know we saw many of you at that lecture, and we’re happy to see all of you here today. I do want to invite all of you after the lecture ends to a public reception in Umrath Lounge foyer, right behind you, that will go until seven o’clock. So you’re all very warmly invited to join us to that. As the largest religious communion in the United States, Roman Catholicism is and long has been immensely influential in American political and civil life. From social justice issues to church/state debates, from questions about immigration to the death penalty to the market economy to sexuality and abortion, Catholicism has been central to shaping American public discourse and American political debates over matters of deep consequence to all of our lives. Catholics, once a small minority in a sea of American Protestants, have a proud tradition of dissent against U.S. values and assumptions, best known in noted figures such as Dorothy Day, Cesar Chavez, Simone Camel of the Nuns on the Bus, and Daniel Berrigan, about whose Applied Christianity, by the way, Senator Danforth’s own daughter, Mary Danforth Stillman, wrote her undergraduate senior thesis at Princeton. -

Page 1 of 215 11:48:23AM Club Information Report CUS9503 10/09

Run Date: 10/09/2020 Key Club CUS9503 Run Time: 11:48:23AM Club Information Report Page 1 of 215 Class: KCCLUB Districts from H01 to H99 Admin. Start Date 10/01/2019 to 09/30/2020 Club Name State Club ID Sts Club Advisor Pd Date Mbr Cnt Pd Amount Kiwanis Sponsor Club ID Div H01 - Alabama Abbeville Christian Academy AL H90124 Debbie Barnes 12/03/2019 34 238.00 Abbeville K04677 K0111 Abbeville High School AL H87789 Valerie Roberson 01/28/2020 12 84.00 Abbeville K04677 K0111 Addison High School AL H92277 Mrs Brook Beam 12/09/2019 30 210.00 Cullman K00468 K0102 Alabama Christian Academy AL H89446 Page Clayton 06/04/2020 93 651.00 Montgomery K00174 K0109 Alabama School Of Mathematics And S AL H88720 Derek V Barry 01/07/2020 39 273.00 Azalea City, Mobile K10440 K0114 Alexandria High School AL H89049 Maria Dickson 11/09/2019 29 203.00 Anniston K00277 K0107 American Christian Academy AL H94160 Josh Albright 0 Tuscaloosa K00457 K0104 Andalusia High School AL H80592 Daniel Bulger 12/05/2019 15 105.00 Andalusia K03084 K0112 Anniston High School AL H92151 Kristi Shelton 0 Ashford High School AL H83507 LuAnn Whitten 01/24/2020 7 49.00 Dothan K00306 K0111 Auburn High School AL H81645 Marie Cerio 03/25/2020 4 28.00 Auburn K01720 K0110 Austin High School AL H90675 Dawn Wimberley 12/12/2019 36 252.00 Decatur K00230 K0102 B.B. Comer Memorial School AL H89769 Gavin McCartney 12/10/2019 31 217.00 Sylacauga K04178 K0108 Baker High School AL H86128 Andrew Lipske 11/09/2019 175 1,225.00 Mobile K00139 K0114 Baldwin County High School AL H80951 Sandra Stacey 02/20/2020 61 427.00 Bayside Academy AL H92084 Rochelle Tripp 12/13/2019 53 371.00 Daphne-Spanish Fort K13360 K0113 Beauregard High School AL H91788 C Scott Fleming 11/11/2019 26 182.00 Opelika K00241 K0110 Benjamin Russell High School AL H80742 Mandi Burr 12/02/2019 59 413.00 Alexander City K02901 K0110 Bessemer Academy AL H90624 Candace Griffin 0 Bessemer K00229 K0106 Bob Jones High School AL H86997 Shari Windsor 12/18/2019 51 357.00 Booker T.