The Role of Archbishop Joseph F. Rummel in the Desegregation of Catholic Schools in New Orleans by John Smestad Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Apostolate: New Opportunities in the Local Church

IV. PARISH APOSTOLATE: NEW OPPORTUNITIES IN THE LOCAL CHURCH by John E. Rybolt, C.M. Beginning with the original contract establishing the Community, 17 April 1625, Vincentians have worked in parishes. At fIrst they merely assisted diocesan pastors, but with the foundation at Toul in 1635, the fIrst outside of Paris, they assumed local pastorates. Saint Vincent himself had been the pastor of Clichy-Ia-Garenne near Paris (1612-1625), and briefly (1617) of Buenans and Chatillon les-Dombes in the diocese of Lyons. Later, as superior general, he accepted eight parish foundations for his community. He did so with some misgiving, however, fearing the abandonment of the country poor. A letter of 1653 presents at least part of his outlook: ., .parishes are not our affair. We have very few, as you know, and those that we have have been given to us against our will, or by our founders or by their lordships the bishops, whom we cannot refuse in order not to be on bad terms with them, and perhaps the one in Brial is the last that we will ever accept, because the further along we go, the more we fmd ourselves embarrassed by such matters. l In the same spirit, the early assemblies of the Community insisted that parishes formed an exception to its usual works. The assembly of 1724 states what other Vincentian documents often said: Parishes should not ordinarily be accepted, but they may be accepted on the rare occasions when the superior general .. , [and] his consul tors judge it expedient in the Lord.2 229 Beginnings to 1830 The founding document of the Community's mission in the United States signed by Bishop Louis Dubourg, Fathers Domenico Sicardi and Felix De Andreis, spells out their attitude toward parishes in the new world, an attitude differing in some respects from that of the 1724 assembly. -

Catholic Educational Exhibit Final Report, World's Columbian

- I Compliments of Brother /Tfcaurelian, f, S. C. SECRETARY AND HANAGER i Seal of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Columbian Exposition, 1893. llpy ' iiiiMiF11 iffljy -JlitfttlliS.. 1 mm II i| lili De La Salle Institute, Chicago, III. Headquarters Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Fair, 1S93. (/ FINAL REPORT. Catholic Educational Exhibit World's Columbian Exposition Ctucaofo, 1893 BY BROTHER MAURELIAN F. S. C, Secretary and Manager^ TO RIGHT REVEREND J. L. SPALDING, D. D., Bishop of Peoria and __-»- President Catholic Educational ExJiibit^ WopIgT^ F^&ip, i8qt I 3 I— DC X 5 a a 02 < cc * 5 P3 2 <1 S w ^ a o X h c «! CD*" to u 3* a H a a ffi 5 h a l_l a o o a a £ 00 B M a o o w a J S"l I w <5 K H h 5 s CO 1=3 s ^2 o a" S 13 < £ a fe O NI — o X r , o a ' X 1 a % a 3 a pl. W o >» Oh Q ^ X H a - o a~ W oo it '3 <»" oa a? w a fc b H o £ a o i-j o a a- < o a Pho S a a X X < 2 a 3 D a a o o a hJ o -^ -< O O w P J tf O - -n>)"i: i i'H-K'i4ui^)i>»-iii^H;M^ m^^r^iw,r^w^ ^-Trww¥r^^^ni^T3r^ -i* 3 Introduction Letter from Rig-lit Reverend J. Ij. Spalding-, D. D., Bishop of Peoria, and President of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, to Brother Maurelian, Secretary and Manag-er. -

Notre Dame Seminary Graduate School of Theology

Notre Dame Seminary Graduate School of theology Academic Catalog 2018 - 2019 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................1 Mission and History .............................................................................................................5 Mission Statement ........................................................................................................5 History ..........................................................................................................................5 Accreditation ........................................................................................................................8 Governance and Administration ..........................................................................................9 Functions of the Board of Trustees ............................................................................11 Functions of the Faculty Council ...............................................................................12 Location and Campus ........................................................................................................13 Student Services .................................................................................................................15 Library ........................................................................................................................15 Bookstore ...................................................................................................................15 -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 13, No. 02

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus IMHHHMHiilHa LU S6c < Notre Dame ALUMNUS O^ o o ^^'«;^5^ > CO UJ > TIMOTHY P. GALVIN, PH.B., '16 Devoted Alumnus President of the Alumni Association Supreme Director, Knights of Columbus Eminent Attorney and Orator November, 1934 34 The 1<lo t T e 'Dame cA lumnus November, 1934 Association; while the Editor may be that our infringement upon the in confined to a large portion of routine; dulgence of the University, no matter CCA4HENT and while the treasury continues to how satisfied Notre Dame may be sufl'er a most pernicious financial with the results, is difBcult to justify '. anemia—^the Association continues a in the face of economic recovery. Radio waves have controlled the definite, even rapid, progress, con While we do not pretend to believe direction of cars, ships, planes, etc., trolled by those radioactive forces that all our members are happily or without the aid of human hands. that have always worked for our profitably employed, we bring up progress, though in normal times again those time-worn contentions The direction of the Notre Danie through human agents. Alumni Association is in somewhat that we still hold to be most moder similar vein now. • ate— five dollars, the annual dues, Bills have been mailed as in the represent very little drain on any The waves of the depression over happy days of yore. No veneer, no form of income. We maintain that whelmed us financially. -

Cement May 9, 1992

CEMENT MAY 9, 1992 ·_···:·:~ ... '":' ··,. WSU Branch Campus and Center Ceremonies Commencement-related ceremonies will be held at all WSU branches and centers according to the following schedule: WSU Intercollegiate Center for Nursing 4:00 p.m., Friday, May 8-The Spokane Education Metropolitan Performing Arts Center WSU Seattle Center for Hotel and 7:00 p.m., Thursday, June I I-Pigott Restaurant Administration Auditorium, Seattle University WSU Spokane 4:00 p.m., Friday, May 8-The Spokane Metropolitan Performing Arts Center WSU Tri-Cities 7:00 p.m., Friday, May IS-Richland High School Auditorium, Richland WSU Vancouver 7:00 p.m., Sunday, May IO-Evergreen High School Auditorium, Vancouver COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES NINETY-SIXTH ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT Nine O'Clock Saturday, May Ninth Nineteen Hundred and Ninety-two Pullman, Washington Commencement Recognition Ceremonies will be held following the All-University Commencement Exercises. Time and location can be found immediately preceding the list of degree candidates, by college. ••• 2 COMMENCEMENT 1992 Washington State University, on the occasion of its 96th annual commencement, cordially welcomes all those who have come to the Pullman campus to share in ceremonies honoring the members of the graduating class of 1992. All are encouraged to attend the College and School Commencement Recognition Ceremonies being held throughout the day. To the members of the Class of 1992, the university extends sincere congratulations. Washington State University is dedicated to the preparation of students for productive lives and profes sional careers, to basic and applied research in a variety of areas, and to the dissemination of knowledge. The university consists of seven colleges, a graduate school, an Intercollegiate Center for Nursing Education in Spokane and Yakima, the Center for Hotel and Restaurant Administration in Seattle, and branch campuses in Spokane, the Tri-Cities, and Vancouver. -

Nation's Necroes Convention

Patronize Our Advertis- GOOD CONDUCT WILL ers — Their Advertising ALWAYS GAIN YOU in this paper shows that RESPECT. Watch Your they appreciate your Public trade. Conduct. MISSISSIPPI, AUGUST 1956 PRICE TEN VOLUME XIV—NUMBER 43 JACKSON, SATURDAY, 18, CENtS EYE DEMO. * CONVENTION NATION'S NECROES I w ************ Democratic national Convention now Underway In Chicago Getting Close Of New Orleans Catholic Schools From The Nation’s — Scrutiny Integration■ Negro Postpone j*. M •---* ui new Voters As Politicians Make Archbishop Joseph itummei Well Known Say Civil Rights Police Break-Up Jesse Owens, One Writes Letter To Diocese Civil Rights A Major Issue Orleans Jackson Man Not Top Concern Anti-Negro Mob Of The Nation’s Of Negro Democratic Leaders Playing Announcing Postponement Faced With Of Voters Near Site Of * Greatest Athletes Important Roles At Convention Schools Negro Integration Of Catholic Negro Voters Cite Democratic Natl. To Be Guest Of Chicago, 111., Aug. 15.—(DSN)— Serious The eyes of the nations cit- Charge Pocketbook Issue Negro SCHOOL TO REMAIN LARGELY Kent Bullock izen in all sections of the country Charged Aug. 14.— were focused on the Demo- NEXT YEAR Minneapolis, Minn., Convention AME Youth Meet i being SEGREGATED UNTIL With Attempted Rape The Negro voter, wholly apart from cratic National Convention which the Negro leader, might surprise Mob Meeting At Campbell got under way here Monday largely La., Aug. 12.— Aroused By New Orleans, In Attacking Young the platform committee. He talks for the reason that top political Rummel an- Here Archbishop Joseph much more about his pocketbook Rumor Of Negro College leaders as well as the leading can- last that integra- j White Couple nounced Sunday and his vote than civil rights and Next Week didates have made civil rights a schools of the In tion of Catholic A well known and prominent his vote. -

===~111===D=~=Ce=M=Be=R==~Ii====~

c. c~ ~====~111===D=~=CE=M=BE=R==~II====~ BISHOPS' ANNUAL MEETING NUMBER -Including- A Report of the Proceedings of the November, 1931, Meeting of the Archbishops and Bishops of the United States Digests of the Annual Reports of the Episcopal Chairmen of the National Catholic Welfare Conference The Bishops' Statement on the Unemployment Crisis ADDITIONAL FEATURES Peace: A Summary Text for Individual Study or for Three Discussions at Group or Organization Meetings; Analysis of the Report of the President's Advisory Com mittee on Education; Full Text of the Resolutions Adopted by the Catholic Rural Life Conference; Reports of Recent Meetings of Diocesan and Deanery Units of the N. C. C. w. An Announcement of Importance to All Our Subscribers (See pages 16-17) Subscription Price VOL. XIII, No. 12 Domes tic-$l.00 per year December, 1931 Foreign-$l.25 per year 2 N. C. W. C. REVIEW December, 1931 N. c. W~ C. REVIEW OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WELFARE CONFERENCE N. C. w. C. Administrative ({This organization (the N. C. Purpose of the N. C. W. C. Committee W. C.) is not only useful, but IN THE WORDS OF OUR HOLY FATHER: MOST REV. EDWARD .T. HANNA, D.D. necessary. .. We praise all "Since you (the Bishops) reside in Archbishop of San FranciscQ cities far apart and there are matters who in any way cooperate in this of a higher imp01't demanding your Chairman great work.N-POPE PIUS XI. joint deliberation. • • . it is im perative that by taking counsel together RT. REV. THOMAS F. -

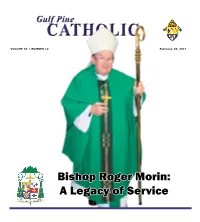

Bishop Roger Morin: a Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P

Gulf Pine CATHOLIC VOLUME 34 / NUMBER 12 February 10, 2017 Bishop Roger Morin: A Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P. Morin Third Bishop of Biloxi (2009 - 2016) Bishop Roger Paul Morin was Orleans. In 1973, he was appointed associate director of Bishop Morin received the Weiss Brotherhood Award installed as the third Bishop of Biloxi the Social Apostolate and in 1975 became the director, presented by the National Conference of Christians and on April 27, 2009, at the Cathedral of responsible for the operation of nine year-round social Jews for his service in the field of human relations. the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin service centers sponsored by the archdiocese. Bishop Bishop Morin was a member of the USCCB’s Mary by the late Archbishop Pietro Morin holds a master of science degree in urban studies Subcommittee on the Catholic Campaign for Human February 10, 2017 • Bishop Morin Sambi, Apostolic Nuncio to the from Tulane University and completed a program in Development 2005-2013, and served as Chairman 2008- United States, and Archbishop 1974 as a community economic developer. He was in 2010. During that time, he also served as a member of Thomas J. Rodi, Metropolitan Archbishop of Mobile. residence at Incarnate Word Parish beginning in 1981 the Committee on Domestic Justice and Human A native of Dracut, Mass., he was born on March 7, and served as pastor there from 1988 through April 2002. Development and the Committee for National 1941, the son of Germain J. and Lillian E. Morin. He has Bishop Morin is the Founding President of Second Collections. -

Via Sapientiae Volume 17: 1946-47

DePaul University Via Sapientiae De Andrein Vincentian Journals and Publications 1947 Volume 17: 1946-47 Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Volume 17: 1946-47. https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in De Andrein by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CS rnIc %NVfa Volume 17 Perryville, Missouri, October, 1946 / No. 1 CONFRERES STAFF NEW SEMINARY Faculty Row and Classrooms with Chapel in Distance Pict:res Courtesy Southwest Courier High School Dormitory Student Dining Room His Excellency, Bishop Eugene J. Mc- homa. It is the completion of a hope Conscious of the grave obligation, the Guinness, has entrusted to the care of long cherished by Bishop McGuinness. Community feels honored in the part the Community the new Preparatory His Excellency is well aware of the it is to take in this new project. Seminary that is destined to serve the need of such a Seminary, and is con- Catholic interests of the State of Okla- fident that the advantages of train- At the present the arrangement at the Seminary is only provisional. It homa. Located at Bethany, the in- ing future priests within the Oklahoma consists of about ten small stitution is about five miles from Okla- City-Tulsa Diocese will more than off- units with homa City and is conveniently reach- siet the sacrifices entailed in the in- two larger houses. -

Via Sapientiae Volume 29: 1958-59

DePaul University Via Sapientiae De Andrein Vincentian Journals and Publications 1959 Volume 29: 1958-59 Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Volume 29: 1958-59. https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in De Andrein by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ae -pet" VOLUME 29 PERRYVILLE, MISSOURI OCTOBER, 1958 NUMBER 1 TWO FILIAL VICE-PROVINCES ESTABLISHED - -- -~--- '' On the feast day of our holy foun- der, St. Vincent de Paul, the Very Reverend John Zimmerman, C.M., as- sistant to the Superior General, in- formed us of the division of our Wes- tern Province into one Mother Province and two Filial Vice-Provinces. He also mentioned that the Very Reverend James W. Stakelum, C.M.V., would remain Provincial of the Midwest area, now known as the Mother Province. The Filial Vice-Provinces will each have a Vice-Provincial, Father Maurice J. Hymel for the South and Father James W. Richardson for the Far West. Father Hymel's headquarters will be in New Orleans where he is Pastor of St. Joseph's Church. Father Richardson will continue to reside in California. In a letter sent to the Community houses, Father Stakelum explained that the division of the Province has a twofold purpose. First of all, more at- tention can now be given to the con- freres and the affairs of each house because both of the Vice-P'rovincials will assume the duties of the Provin- cial in their own Vice-Province. -

The Education of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1989 Race Relations and Community Development: The ducE ation of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960. Donald E. Devore Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Devore, Donald E., "Race Relations and Community Development: The ducaE tion of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960." (1989). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4839. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Trey Ange Diaconate Ordination Aug. 10 LAKE CHARLES – Bishop Year Project,” Ange Said

00964812 Vol. 42, No. 16 Trey Ange diaconate ordination Aug. 10 LAKE CHARLES – Bishop year project,” Ange said. deacon in Austin. He also told cause its broken. You take it revelation and then in Sep- Glen John Provost will ordain It was during his work ex- him that since he was receiv- and heal it and take as much tember 2010 his parents – on Trey Ange, a native of Lake perience in Austin that he felt ing a call at that time, perhaps time with it as you need and the day he was scheduled to Charles and soon a fourth- his first “real” nudge from the he should explore what that then give it back when you are meet with Msgr. (Daniel A.) year theology seminarian Holy Spirit. call might be. done with it because I can’t do Torres, the then Director of at Notre Dame Seminary in “I was 23 years old and re- “I thought, yeah, he was anything with it. Seminarians and Vocations. New Orleans, to the transi- member hearing some sort of insinuating priesthood,” “My heart was such a fer- He finished up his work in tional diaconate, at 6 p.m. on a call for the first time ever,” Ange said. “But, I had already tile seed bed that when the Austin and returned home in Wednesday, August 10 in Our he said. “Previously, I had thought that wasn’t the case. I time came and I received it April 2011. He was sent to St. Lady Queen of Heaven Catho- never heard any kind of call, had discerned previously and back from the Lord, He had Paul Catholic Church in Elton lic Church.