The Omnipresence of Football and the Absence Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Re)Construção De Uma Identidade Coletiva

Da Conceptualização à Operacionalização. A (Re)Construção de uma Identidade Coletiva. Relatório de Estágio Profissionalizante apresentado à Faculdade de Desporto da Universidade do Porto, com vista à obtenção do 2.º ciclo de estudos conducente ao grau de Mestre em Treino de Alto Rendimento Desportivo, nos termos do Decreto-Lei n.º 74/2006 de 24 de Março. Orientador: Professor Doutor José Guilherme Oliveira Tutor no Clube: Miguel Alexandre Areias Lopes Pedro Rodrigues Marques Mané, 200902840 Porto, Setembro de 2018 Ficha de catalogação Mané, P (2018). Da Conceptualização à Operacionalização. A (Re)Construção de uma Identidade Coletiva. Porto: P. Mané. Relatório de Estágio Profissionalizante para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Treino de Alto Rendimento Desportivo, apresentado à Faculdade de Desporto da Universidade do Porto PALAVRAS-CHAVE: ESTÁGIO PROFISSIONAL; FUTEBOL; IDEIA DE JOGO; MODELO DE JOGO; PERIODIZAÇÃO TÁTICA. 2 AGRADECIMENTOS O presente documento espelha o empenho e a dedicação ao longo dos últimos dois anos. Contudo, este caminho foi trilhado na companhia de um conjunto de pessoas que me ampararam, questionaram e contribuíram decisivamente para o meu desenvolvimento, pessoal e profissional. - Ao Professor Doutor José Guilherme, pelos momentos de partilha e pela orientação ao longo do período de elaboração deste documento. - Ao Mister José Tavares, na qualidade de Coordenador Técnico do FC Porto, pela confiança demonstrada ao longo deste período e por todas as aprendizagens inerentes. Por me questionar e por me desafiar constantemente. - Ao Gui e ao Paulinho, pela Amizade e pelo Profissionalismo que revelaram ao longo do ano. O trabalho “invisível” foi de enorme importância e vocês estiveram sempre na linha da frente comigo. -

150331111345.Pdf

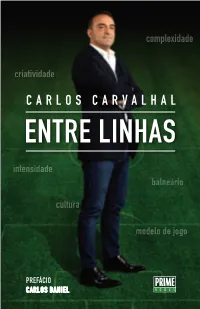

Título Entre Linhas Autor Carlos Carvalhal Design e paginação Jusko® Impressão Cafilesa 1ª edição Novembro 2014 ISBN 978‑989 ‑655 ‑247 ‑3 Depósito legal www.primebooks.pt clientes. [email protected] Índice Prefácio 9 Zé António 13 Paulo Futre 15 Recuperação entre jogos 20 A harmonia de uma orquestra e o futebol 24 Noção de jogar à zona 28 Ter a bola 33 Testes físicos 37 Espaços, linhas e momentos no jogo 41 Amizade e solidariedade... na tarefa 46 Pré‑época 50 Paragens no Campeonato 54 Parar para subir e... descer 58 As lesões e o paradigma do futebol italiano 62 Fadiga mental 65 Mourinho, Lampard e o intervalo de tempo entre dois jogos 69 Como se formatou uma ideia 73 Modelo de jogo 77 A natureza do jogo... do caos à ordem 83 Da teoria à prática e da prática à teoria 87 Intensidade. Um conceito abstrato? 92 Jogadores ou processo? 96 A especificidade ou Especificidade99 “He understands the game...” 105 Os erros vistos pela natureza “sistémica” do jogo 109 Transições ofensivas 113 Momento de transição defensiva 117 As análises de jogo... ou o perigo de fragmentar sem entender 120 A fluidez do jogo124 Pressionar ou bascular 128 Jogador de qualidade ou jogador com qualidades 130 Defesas centrais 133 Trinco ou pivot defensivo, um olhar por dentro do campo 138 Espaços “cegos” 141 Será possível haver pressão numa panela sem testo? 144 Rotatividade 148 A estratégia... 152 Criatividade: reflexão sobre uma palestra de Sir Ken Robinson 155 Quando tudo se começa a... perder 160 Partir do que conheço melhor para o que conheço pior.. -

Análisis Del Mercado Mundial De Jugadores De Fútbol De Alto Nivel: Periodo 2000-2007

. ........ Análisis del mercado mundial de jugadores de fútbol de alto nivel: periodo 2000-2007. Autores: Profesor Dr. Ignacio Urrutia de Hoyos. Profesor Dr. Angel Barajas. D. Fernando Martín. ........Objetivos del informe Análisis del mercado mundial de jugadores de fútbol de alto nivel: periodo 2000-2007. Página 2 de 134 Informe sobre el mercado de traspasos de futbolistas Objetivos del informe sobre el mercado de traspaso de futbolistas desde 2000 a 2007 El informe que presentamos tiene como principal objetivo describir el funcionamiento del mercado mundial de fichajes de jugadores de fútbol de alto nivel. Lo hemos realizado tomando los datos de los traspasos realizados desde la temporada 2000 hasta la 2007. Incluimos un detalle en profundidad de lo sucedido en el año 2007, tanto en el mercado de verano como en el invierno. El informe que presentamos tiene interés porque se refiere a los jugadores con más talento del mundo. Podríamos haber hecho un análisis sobre todos los jugadores traspasados. Sin embargo, eso implicaría una ingente tarea de recopilación de datos que además sería, en muchos casos, dependiendo de las ligas y países, imposible de abarcar. Uno de los primeros parámetros a definir fue el de jugador de alto nivel. Hemos calificado el alto nivel a partir del importe de la inversión a realizar para poder disfrutar con su talento. Así, hemos considerado de alto nivel a todo jugador cuyo traspaso supere la cifra de 10 millones de euros. El informe pretende valorar los aspectos fundamentales para la explicación del precio que pagado por un jugador. Este es nuestro primer informe de manera que esperamos mejorarlo a medida que podamos ir plasmando nuestras investigaciones académicas. -

Going Political – Multimodal Metaphor Framings on a Cover of the Sports Newspaper a Bola

Going political – multimodal metaphor framings on a cover of the sports newspaper A Bola Maria Clotilde Almeida*1 Abstract This paper analyses a political-oriented multimodal metaphor on a cover of the sports newspaper A Bola, sequencing another study on multimodal metaphors deployed on the covers of the very same sports newspaper pertaining to the 2014 Football World Cup in Brazil (ALMEIDA/SOUsa, 2015) in the light of Forceville (2009, 2012). The fact that European politics is mapped onto football in multimodal metaphors on this sports newspaper cover draws on the interplay of conceptual metaphors, respectively in the visual mode and in the written mode. Furthermore, there is a relevant time-bound leitmotif which motivates the mapping of politics onto football in the sports newspaper A Bola, namely the upcoming football match between Portugal and Germany. In the multimodal framing of the story line under analysis. The visual mode apparently assumes preponderance, since a picture of Angela Merkel, a prominent leader of EU, is clearly overshadowed by a large picture of Cristiano Ronaldo, the captain of the Portuguese National Football team. However, the visual modality of Cristiano Ronaldo’s dominance over Angela Merkel is intertwined with the powerful metaphorical headline “Vamos expulsar a Alemanha do Euro” (“Let’s kick Germany out of the European Championship”), intended to boost the courage of the Portuguese national football team: “Go Portugal – you can win this time!”. Thus, differently from multimodal metaphors on other covers of the same newspaper, the visual modality in this case cannot be considered the dominant factor in multimodal meaning creation in this politically-oriented layout. -

E:\Volume2.CD-Rom\6.Conjunto Global Dos Textos Em Formato .Txt

txt2/textos_dos_jornais_portugueses-Correio-10_janeiro-opinião2.10_jan.doc.txt O valor das palavras No último Mundial de Futebol ficámos a conhecer a vuvuzela, uma espécie de corneta com um som entre a sirene e o elefante que é capaz de despertar no monge o espírito de um taliban. Em 2010, 'vuvuzela' foi a nossa palavra do ano, e se dúvidas existiam, confirmámos então que é mais fácil recordar o que pior nos faz. No ano anterior, 2009, graças a Ricardo Araújo Pereira & Cia, é certo, mas, particularmente, às eleições e aos políticos que tínhamos (e ainda temos), ganhou 'esmiuçar', "vocábulo utilizado quando se pretende examinar algo minuciosamente, reduzir a fragmentos, a pó, a esmigalhar ou a esfarelar", segundo o dicionário. Em 25 minutos, na TV, com 'Gato Fedorento esmiuça os sufrágios', este país de poetas passou a saber o valor da palavra referida. Passada a vontade de esmiuçá-los e de esmiuçarmo-nos, e pontapeados pela semântica da economia, elegemos 'austeridade' para 2011. Bateu 'esperança' e até 'troika' e nem a certeza de que já estão a vir 'charters' vingou. Austeridade é "a qualidade de quem é austero"; é "severidade e rigor"; "cuidado escrupuloso em não se deixar dominar pelo que agrada aos sentidos ou deleita a concupiscência". E está tudo dito. Fernanda Cachão * Editora de CORREIO DOMINGO txt2/textos_dos_jornais_portugueses-Correio-10_janeiro-Entrevista.10jan.doc.txt Sandra Cóias confessa não ser mulher de fazer planos para o futuro. A actriz, que diz preferir fazer séries ou cinema, está a aproveitar o fim das gravações de 'Pai à Força' (RTP 1) para participar em castings "Ritmo das novelas não me agrada" – Que projectos tem em mãos neste momento? – Fui a um casting para televisão mas não posso falar sobre o assunto. -

SL Benfica B CD Nacional

JORNADA 1 SL Benfica B CD Nacional Domingo, 08 de Agosto 2021 - 18:00 Benfica Campus - Campo n.º 1, Seixal POWERED BY Jornada 1 SL Benfica B X CD Nacional 2 Confronto histórico Ver mais detalhes SL Benfica B 2 2 2 CD Nacional GOLOS / MÉDIA VITÓRIAS EMPATES VITÓRIAS GOLOS / MÉDIA 7 golos marcados, uma média de 1,17 golos/jogo 33% 33% 33% 9 golos marcados, uma média de 1,5 golos/jogo TOTAL SL BENFICA B (CASA) CD NACIONAL (CASA) CAMPO NEUTRO J SLB E CDN GOLOS SLB E CDN GOLOS SLB E CDN GOLOS SLB E CDN GOLOS Total 6 2 2 2 7 9 1 2 0 4 3 1 0 2 3 6 0 0 0 0 0 Liga Portugal 2 4 1 1 2 4 7 1 1 0 3 2 0 0 2 1 5 0 0 0 0 0 II Divisão B 2 1 1 0 3 2 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 J=Jogos, E=Empates, SLB=SL Benfica B, CDN=CD Nacional FACTOS SL BENFICA B FACTOS CD NACIONAL TOTAIS TOTAIS 83% em que marcou 83% em que marcou 83% em que sofreu golos 83% em que sofreu golos MÁXIMO MÁXIMO 1 Jogos a vencer 1 Jogos a vencer 3 Jogos sem vencer 2000-03-26 -> 2018-01-20 3 Jogos sem vencer 1999-10-31 -> 2017-08-13 1 Jogos a perder 1 Jogos a perder 3 Jogos sem perder 1999-10-31 -> 2017-08-13 3 Jogos sem perder 2000-03-26 -> 2018-01-20 RECORDES SL BENFICA B: MAIOR VITÓRIA EM CASA LigaPro 19/20 SL Benfica B 1-0 CD Nacional SL BENFICA B: MAIOR VITÓRIA FORA II B Zona Sul 99/00 CD Nacional 1-2 SL Benfica B CD NACIONAL: MAIOR VITÓRIA EM CASA LigaPro 19/20 CD Nacional 3-1 SL Benfica B Ledman LigaPro 17/18 CD Nacional 2-0 SL Benfica B ÚLTIMOS 10 JOGOS DATA JOGO COMPETIÇÃO MARCADORES Brayan Riascos 45 João Camacho 56 Branimir Kalaica 88 (p.b.) ; Pedro Álvaro 2020-03-08 CD Nacional -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3

1 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 4 Contents Foreword by David A. L. Levy 5 3.12 Hungary 84 Methodology 6 3.13 Ireland 86 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.14 Italy 88 3.15 Netherlands 90 SECTION 1 3.16 Norway 92 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 8 3.17 Poland 94 3.18 Portugal 96 SECTION 2 3.19 Romania 98 Further Analysis and International Comparison 32 3.20 Slovakia 100 2.1 The Impact of Greater News Literacy 34 3.21 Spain 102 2.2 Misinformation and Disinformation Unpacked 38 3.22 Sweden 104 2.3 Which Brands do we Trust and Why? 42 3.23 Switzerland 106 2.4 Who Uses Alternative and Partisan News Brands? 45 3.24 Turkey 108 2.5 Donations & Crowdfunding: an Emerging Opportunity? 49 Americas 2.6 The Rise of Messaging Apps for News 52 3.25 United States 112 2.7 Podcasts and New Audio Strategies 55 3.26 Argentina 114 3.27 Brazil 116 SECTION 3 3.28 Canada 118 Analysis by Country 58 3.29 Chile 120 Europe 3.30 Mexico 122 3.01 United Kingdom 62 Asia Pacific 3.02 Austria 64 3.31 Australia 126 3.03 Belgium 66 3.32 Hong Kong 128 3.04 Bulgaria 68 3.33 Japan 130 3.05 Croatia 70 3.34 Malaysia 132 3.06 Czech Republic 72 3.35 Singapore 134 3.07 Denmark 74 3.36 South Korea 136 3.08 Finland 76 3.37 Taiwan 138 3.09 France 78 3.10 Germany 80 SECTION 4 3.11 Greece 82 Postscript and Further Reading 140 4 / 5 Foreword Dr David A. -

Overview & Vision 2018-2022 Application Summary

OVERVIEW OBJECTIVES ORGANIZATION OF EVALUATION CRITERIA VISION FOR 2018-2022 THE CINTESIS UNIT PARTICIPATING ACCOMPLISHMENTS FOR 2018-2022 INSTITUTIONS APPLICATION SUMMARY Center for Health Technology and Services Research cintesis.eu OVERVIEW & VISION 2018-2022 title cintesis: Overview and Vision 2018-2022 editors Altamiro Costa Pereira António Soares co-editors Cláudia Azevedo Olga Estrela Magalhães Milaydis Sosa Napolskij graphic design Bárbara Mota Pedro Sacadura photography Alfredo Mendes de Castro/cintesis Bárbara Mota/cintesis Cláudia Azevedo/cintesis Egídio Santos/uporto Miguel Nunes/fmup Olga Estrela Magalhães/cintesis Pedro Granadeiro/cintesis ipo/cintesis uaveiro/cintesis 2 Overview 4 Vision 5 Objectives 9 Main Accomplishments 10 Organization 32 Evaluation Criteria 37 Institutions 40 Abbreviations & Acronyms 42 Researchers cintesis: overview & vision 2018-2022 2 overview Overview cintesis is a health research unit comprising 485 of inclusiveness and scientific capacitation. In researchers from 46 institutions from all Portuguese particular, cintesis aims to foster strong research regions (including Madeira and Azores) that teams in often neglected professional areas, collaborates with international researchers from over geographical regions, and scientific fields (e.g., Clinical 50 institutions around Europe, North America and Research, Public Health, Primary Care, and Nursing). Portuguese-speaking countries. This unit consists of Thus, cintesis is focused on creating opportunities a multidisciplinary health research cluster working for less appealing regions to be able to attract qualified to promote high-quality and high-impact scientific health researchers, thus leading to a better distribution outputs while addressing relevant societal issues and of human and capital resources within our National increasing technology transfer to the health industry. Scientific and Health Systems. -

CARLOS CARVALHAL CARLOS CARVALHAL BRUNO LAGE • JOÃO MÁRIO OLIVEIRA Possui a Quali Cação UEFA - PRO Licence Atribuida Pela FPF (4Th Grade PRO Coaching Award)

CARLOS CARVALHAL CARLOS CARVALHAL BRUNO LAGE • JOÃO MÁRIO OLIVEIRA Possui a qualicação UEFA - PRO Licence atribuida pela FPF (4th grade PRO Coaching Award). Preletor em vários cursos UEFA - PRO decorridos em Portugal. Treinador de futebol em diversas equipas em Portugal, Grécia e Turquia, entre outras, Sporting Clube de Portugal, Sporting Clube de Braga, Asteras Tripolis, Besiktas. Em Portugal foi vencedor da 1ª edição da Taça da Liga (Vitória de Setúbal) e nalista da Taça de Portugal e Supertaça (Leixões, então na 3ª divisão). Apurou diversas equipas e disputou vários jogos nas competições da UEFA. Galardoado com os prémios “José Maria Pedroto”, em 2008; “Cândido de Oliveira”, em 2007; e “Fernando Vaz”, em 2004, pela Associação Nacional de Treinadores de Futebol. Licenciado em Ciências do Desporto e de Educação Física com especialização em Alto Rendimento - Futebol. Autor do livro “Recuperação... é muito mais do que recuperar”. BRUNO LAGE FILOSOFIA • MODELO DE JOGO • EXERCÍCIOS ESPECÍFICOS • MORFOCICLO DO BESIKTAS Licenciado em Educação Física, Saúde e Desporto, com especialização em Futebol, iniciou a carreira como treinador adjunto nas camadas jovens do Vitória de Setúbal em 1997/98. Treinou o UF Comércio e Indústria (1ª Divisão Distrital) como treinador principal, e como adjunto nos AD Fazendense (3ª Divisão), Est. Vendas Novas (3ª Divisão e 2ª Divisão B) e SU Sintrense (3ª Divisão). Paralelamente colaborou na Escolinha de Futebol Quinito, tendo desempenhado as funções de treinador e coordenador técnico. Em 2004/05 ingressou nas camadas jovens do Sport Lisboa e Benca, onde treinou os escalões de Escolas, Iniciados, Juvenis e Juniores tendo conquistado dois campeonatos nacionais e dois distritais. -

Diários Desportivos Em Portugal E Espanha

Rita Araújo de Morais _________________________________________________________ Diários Desportivos em Portugal e Espanha: uma análise comparativa _________________________________________________________ Universidade Fernando Pessoa Porto 2014 Rita Araújo de Morais _________________________________________________________ Diários Desportivos em Portugal e Espanha: uma análise comparativa _________________________________________________________ Universidade Fernando Pessoa Porto 2014 Rita Araújo de Morais Diários Desportivos em Portugal e Espanha: uma análise comparativa ………………………………………. (A autora, Rita Araújo de Morais) Trabalho apresentado à Universidade Fernando Pessoa como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de mestrado em Ciências da Comunicação – Jornalismo. Orientador: Professor Doutor Jorge Pedro Sousa Agradecimentos Quero manifestar o meu reconhecimento a todos aqueles que me ajudaram durante a realização deste trabalho. Devo destacar o meu orientador, Prof. Doutor Jorge Pedro Sousa pela disponibilidade permanente e pelo incentivo que sempre expressou, assim como todos os Professores do Mestrado de Ciências da Comunicação – Jornalismo pela colaboração. Agradeço aos meus pais que sempre me apoiaram incondicionalmente e que sem eles não teria sido possível frequentar o curso que realmente desejava. Por último, gostaria também de agradecer aos meus avós, ao meu tio Jorge, ao meu primo Ruca e em especial à minha tia Kika que sempre se mostraram disponíveis para me ajudar ao longo de toda a minha vida. Resumo Diários Desportivos em Portugal e Espanha: Uma análise comparativa O projeto em estudo visa uma análise de conteúdos da imprensa diária desportiva portuguesa e espanhola, mais concretamente entre os seguintes seis jornais: A Bola , Record , O Jogo , Mundo Deportivo , Marca e AS . Para compreender esta área, tentamos perceber as diferenças e semelhanças do jornalismo desportivo nos dois países, a partir da amostra recolhida de 15 de outubro a 15 de novembro de 2013. -

Último Encontro Antes Do Embate Com a Suécia

COMITIVA PROGRAMA SELEÇÃO NACIONAL 02.09.2013 segunda-feira 15h00 Contactos informais com os OCS em Óbidos Hotel Marriot, Praia d’El Rey Até às 15h00 Concentração dos jogadores em Óbidos Hotel Marriot, Praia d’El Rey 17h30 Treino (Fechado – 15 minutos OCS) Campo de treinos do Hotel Marriot 03.09.2013 terça-feira 10h30 Treino (Fechado – 15 minutos OCS) Campo de treinos do Hotel Marriot 12h45 Roda de Imprensa com um jogador em Óbidos Hotel Marriot, Praia d’El Rey 04.09.2013 quarta-feira 10h30 Treino (Fechado – 15 minutos OCS) Campo de treinos do Hotel Marriot 12h45 Roda de Imprensa com um jogador em Óbidos Hotel Marriot, Praia d’El Rey 05.09.2013 quinta-feira 10h25 Partida de Lisboa para Belfast Voo MZ 6441 13h15 Chegada a Belfast 19h30 Treino em Besfast Windsor Park Após o treino Conferência de Imprensa com o Selecionador Windsor Park Nacional, Paulo Bento, em Belfast 06.09.2013 sexta-feira 19h45 Jogo IRLANDA DO NORTE vs PORTUGAL Windsor Park Após o jogo Conferência de Imprensa com o Selecionador Windsor Park Nacional, Paulo Bento, e Zona Mista 00h00 Partida de Belfast para Boston Voo MZ 6451 07.09.2013 sábado 02h00 Chegada a Boston 17h00 Treino (Fechado – 15 minutos OCS) Campo de Treinos Gillette Stadium 08.09.2013 domingo Antes do treino Roda de Imprensa com um jogador Campo de Treinos Gillette Stadium 10h00 Treino (Fechado – 15 minutos OCS) Campo de Treinos Gillette Stadium 09.09.2013 segunda-feira 15h00 Conferência de Imprensa com o Selecionador Gillette Stadium Nacional, Paulo Bento 19h30 Treino (Fechado – 15 minutos OCS) Gillette Stadium 10.09.2013 terça-feira 21h00 Jogo BRASIL vs PORTUGAL Gillette Stadium Após o jogo Conferência de Imprensa com o Selecionador Gillette Stadium Nacional, Paulo Bento, e Zona Mista 11.09.2013 quarta-feira 02h00 Partida de Boston Voo MZ 6432 13h05 Chegada a Lisboa Nota: As horas indicadas no programa são as locais.