Country Gap Report Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poverty Map Report

Poverty Maps of Uganda Mapping the Spatial Distribution of Poor Households and Child Poverty Based on Data from the 2016/17 Uganda National Household Survey and the 2014 National Housing and Population Census Technical Report October 2019 1 Acknowledgement This technical report presents the results of the Uganda poverty map update exercise, which was conducted by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) in close collaboration with UNICEF and the World Bank. The core task team at UBOS consisted of Mr. James Muwonge (Director of Socio-Economic Surveys), Mr. Justus Bernard Muhwezi (Manager of Geo-Information Services), Mr. Stephen Baryahirwa (Principal Statistician and Head of the Household Surveys Unit), Mr. Vincent Ssennono (Principal Statistician and Head of the Methodology and Analysis Unit), and Mr. Adriku Charles (Senior Geo-Information Officer). The core task team at the World Bank consisted of Dr. Nobuo Yoshida (Lead Economist), Dr. Carolina Mejia-Mantilla (Uganda Country Poverty Economist), Dr. Minh Cong Nguyen (Senior Economist) and Ms. Miyoko Asai (Consultant). Dr. Nobuo Yoshida and Dr. Minh Cong Nguyen supervised the exercise and ensured that the latest international experience and technical innovations were available to the team. The core task team in UNICEF consisted of Dr. Diego Angemi (Chief Social Policy and Advocacy), Mr. Arthur Muteesasira (Information Management and GIS Officer), and Ms. Sarah Kabaija (Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist). The team benefited from the support and guidance provided by Dr. Robin D. Kibuka(Chairman of the Board, UBOS), Ms. Doreen Mulenga (Country Representative, UNICEF), Mr. Antony Thompson (Country Manager, World Bank), and Dr. Pierella Paci (Practice Manager, World Bank). -

Emergency Health Fiscal and Growth Stabilization and Development

LIST OF COVID-19 QUARANTINE CENTRES IN WATER AND POWER UTILITIES OPERATION AREAS WATER S/N QUARANTINE CENTRE LOCATION POWER UTILITY UTILITY 1 MASAFU GENERAL HOSPITAL BUSIA UWS-E UMEME LTD 2 BUSWALE SECONDARY SCHOOL NAMAYINGO UWS-E UMEME LTD 3 KATAKWI ISOLATION CENTRE KATAKWI UWS-E UMEME LTD 4 BUKWO HC IV BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 5 AMANANG SECONDARY SCHOOL BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 6 BUKIGAI HC III BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 7 BULUCHEKE SECONDARY SCHOOL BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 8 KATIKIT P/S-AMUDAT DISTRICT KATIKIT UWS-K UEDCL 9 NAMALU P/S- NAKAPIRIPIRIT DISTRICT NAMALU UWS-K UEDCL 10 ARENGESIEP S.S-NABILATUK DISTRICT ARENGESIEP UWS-K UEDCL 11 ABIM S.S- ABIM DISTRICT ABIM UWS-K UEDCL 12 KARENGA GIRLS P/S-KARENGA DISTRICT KARENGA UWS-K UMEME LTD 13 NAKAPELIMORU P/S- KOTIDO DISTRICT NAKAPELIMORU UWS-K UEDCL KOBULIN VOCATIONAL TRAINING CENTER- 14 NAPAK UWS-K UEDCL NAPAK DISTRICT 15 NADUNGET HCIII -MOROTO DISTRICT NADUNGET UWS-K UEDCL 16 AMOLATAR SS AMOLATAR UWS-N UEDCL 17 OYAM OYAM UWS-N UMEME LTD 18 PADIBE IN LAMWO DISTRICT LAMWO UWS-N UMEME LTD 19 OPIT IN OMORO OMORO UWS-N UMEME LTD 20 PABBO SS IN AMURU AMURU UWS-N UEDCL 21 DOUGLAS VILLA HOSTELS MAKERERE NWSC UMEME LTD 22 OLIMPIA HOSTEL KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD 23 LUTAYA GEOFREY NAJJANANKUMBI NWSC UMEME LTD 24 SEKYETE SHEM KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD PLOT 27 BLKS A-F AKII 25 THE EMIN PASHA HOTEL NWSC UMEME LTD BUA RD 26 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD 27 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIGOWA NTINDA NWSC UMEME LTD 28 MARIUM S SANTA KYEYUNE KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD JINJA SCHOOL OF NURSING AND CLIVE ROAD JINJA 29 MIDWIFERY A/C UNDER MIN.OF P.O.BOX 43, JINJA, NWSC UMEME LTD EDUCATION& SPORTS UGANDA BUGONGA ROAD FTI 30 MAAIF(FISHERIES TRAINING INSTITUTE) NWSC UMEME LTD SCHOOL PLOT 4 GOWERS 31 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 2 GOWERS 32 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 45/47 CHURCH 33 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD RD CENTRAL I INSTITUTE OF SURVEY & LAND PLOT B 2-5 STEVEN 34 NWSC 0 MANAGEMENT KABUYE CLOSE 35 SURVEY TRAINING SCHOOL GOWERS PARK NWSC 0 DIVISION B - 36 DR. -

The Contents of the Different Baskets Are Listed Below

MINISTRY OF HEALTH PHARMACY DEPARTMENT JUNE 2020 FACILITY TRACER MEDICINES STOCK STATUS REPORT A Publication of the Ministry of Health Uganda This monthly report on the facility stock status of the 41 tracer items (in different baskets) provides information about the stock situation of health facilities in the country in order to inform the Ministry of Health and all stakeholders to make appropriate logistics decisions that ensure an effective health commodities supply chain. The report shows the number and percentages of facilities that are appropriately stocked, over stocked or out of stock by level of care and ownership based on Months of Stock (MOS). The MOS highlights the number of months a product will last based on the present consumption rate. It also further indicates facilities that have over 8 months of stock (MOS) broken down by level of care and ownership. The report shows the availability of the different and overall baskets using two indicators i.e. 1) Average percentage availability of a basket of 41 commodities based on all reporting facilities in the previous cycle Definition : Availability is measured as the number of days for which a specific commodity was in stock at the facility store during the reporting period. 2) Percentage of facilities that had over 95% availability of a basket of commodities in the previous cycle Definition : This indicator measures the % of health facilities that reported having the basket of commodities available during the reporting period. The contents of the different baskets are listed -

Food Security and Livelihoods in Areas Affected by Desert Locusts September 2020 Assessment Report

Uganda Food security and livelihoods in areas affected by desert locusts September 2020 Assessment report Uganda Food security and livelihoods in areas affected by desert locusts September 2020 Assessment report Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2021 REQUIRED CITATION FAO. 2021. Uganda – Food security and livelihoods in areas affected by desert locusts, September 2020. Assessment report. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb6389en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. ISBN 978-92-5-134840-6 ©FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. -

Nakapiripirit District Local Government Councils' Scorecard FY 2018/19

nakapiripirit DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 nakapiripirit DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 L-R: Ms. Rose Gamwera, Secretary General ULGA; Mr. Ben Kumumanya, PS. MoLG and Dr. Arthur Bainomugisha, Executive Director ACODE in a group photo with award winners at the launch of the 8th Local Government Councils Scorecard Report FY 2018/19 at Hotel Africana in Kampala on 10th March 2020 1.0 Introduction the southwest, Kumi district to the west and Katakwi district to This brief is developed from the main the northwest. The district has 5 Scorecard Report titled “The Local sub counties including; Namalu, Government Councils Scorecard Loregae, Kakomongole, Moruita FY 2018/19. The Next Big Steps: and Nakapiripirit Town Council Consolidating Gains of Decentralisation with a total population of 88,281 and Repositioning the Local Government (42,565 male and 45,716 female) Sector in Uganda.” The brief report as per the 2014 population census. highlights the performance of elected leaders and Council of Nakapiripirit District Local Government. 1.2 The Local Government Councils Scorecard 1.1 Brief about Nakapiripirit District Initiative (LGCSCI) Nakapiripit district is located in northeastern The main building blocks in Uganda; bordered by Napak district to the LGCSCI are the principles and north, Nabilatuk district to the northeast, core responsibilities of Local Amudat district to the east, Kween district Governments as set out in Chapter to the southeast, Bulambuli district to 11 of the Constitution of the Republic Eugene Gerald Ssemakula • Kiru1 Simon Alasco • Jenifer Auma nakapiripirit DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 of Uganda, the Local Governments 2.0 Results of the Assessment Act (CAP 243) under Section 10 This section highlights the performance of (c), (d) and (e). -

Developed Special Postcodes

REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF INFORMATION & COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AND NATIONAL GUIDANCE DEVELOPED SPECIAL POSTCODES DECEMBER 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS KAMPALA 100 ......................................................................................................................................... 3 EASTERN UGANDA 200 ........................................................................................................................... 5 CENTRAL UGANDA 300 ........................................................................................................................... 8 WESTERN UGANDA 400 ........................................................................................................................ 10 MID WESTERN 500 ................................................................................................................................ 11 WESTNILE 600 ....................................................................................................................................... 13 NORTHERN UGANDA 700 ..................................................................................................................... 14 NORTH EASTERN 800 ............................................................................................................................ 15 KAMPALA 100 No. AREA POSTCODE 1. State House 10000 2. Parliament Uganda 10001 3. Office of the President 10002 4. Office of the Prime Minister 10003 5. High Court 10004 6. Kampala Capital City Authority 10005 7. Central Division 10006 -

USAID-PACT-Karamoja-Success

USAID Program for Accelerated Control of TB in Karamoja SUCCESS STORIES DISCLAIMER: USAID PACT-Karamoja made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this storybook are the responsibility of IDI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. About PACT-Karamoja Where We Work Period: 2020 - 2025 Funder Project Goal Scale-up evidence-based and high-impact interventions towards the achievement of End TB strategy targets of 90% treatment coverage and treatment success through health system strengthening in all districts of the Karamoja sub-region. Project Objectives Improve treatment success rates to 90% Improve case detection rates to 85% Improve cure rates to at least 70% Our Partners The USAID Program for Accelerated Control of TB in Karamoja (PACT Karamoja) is implemented by the Infectious Diseases Institute Ltd (IDI) with its partner: Dr. Achar, District Health Officer Kotido district receiving one of motor bikes donated by the Project from Chief of Party, USAID PACT-Karamoja. USAID Support Improved TB Patient Tracking Among Nomadic Populations in Karamoja Sub-region Ruto, however, did not give up on finding Margaret. He continued to check if Margaret had returned to her home whenever he visited other TB patients in Kukayim village for adherence support. He also regularly called her next of kin to find out if Margaret had returned from Ochorichor village. After five months of tracking Margaret, Ruto found her back at her home unwell. He encouraged her to return to Amudat hospital for review by the health workers. -

UGANDA - KARAMOJA IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS OVERVIEW of the IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS FEBRUARY 2021 - JANUARY 2022 of KARAMOJA Issued July 2021

UGANDA - KARAMOJA IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS OVERVIEW OF THE IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS FEBRUARY 2021 - JANUARY 2022 OF KARAMOJA Issued July 2021 KEY FIGURES FEBRUARY 2021 - JANUARY 2022 Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) 10,257 56,560 Moderate Acute cases of children aged Malnutrition (MAM) 6-59 months acutely 46,303 malnourished 10,208 IN NEED OF TREATMENT cases of pregnant or lactating women acutely malnourished IN NEED OF TREATMENT Current AMN February - July 2021 Overview How Severe, How Many and When: According to the latest IPC Acute Malnutrition (AMN) analysis, during the lean season of 2021, February – July 2021, of the nine districts in Karamoja region, one district has Critical levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase 4), four districts have Serious levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase 3) and another four districts have Alert levels of 1 - Acceptable 5 - Extremely critical Map Symbols Evidence Level acute malnutrition (IPC AMN PhaseAcceptable 2). About 56,600 children in the nine districts Phase classification Urban settlement * 2 - Alert based on MUAC classification ** Medium included in the analysis are affectedHigh by acute malnutrition and are in need of 3 - Serious Areas with inadequate *** evidence IDPs/other settlements Scarce evidence due treatment. Approximatelyclassification 46,300to childrenlimited or no are moderately malnourished while 4 - Critical Areas not analysedover 10,200 children are severelyhumanitarian malnourished. access Around 10,200 pregnant or 1 - Acceptable 5 - Extremely critical Map Symbols Evidence Level lactating women areAcceptable also acute malnourished. Phase classification Urban settlement * 2 - Alert based on MUAC classification ** Medium High 3 - Serious Areas with inadequate Where: Kaabong*** district has Critical levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase evidence IDPs/other settlements Scarce evidence due classification4) with a Global Acuteto limited Malnutrition or no (GAM) prevalence of 18.6%. -

Assessment Form

Local Government Performance Assessment Nabilatuk District (Vote Code: 623) Assessment Scores Accountability Requirements % Crosscutting Performance Measures 78% Educational Performance Measures 59% Health Performance Measures 64% Water & Environment Performance Measures 43% 623 Accountability Requirements 2019 Nabilatuk District Definition of No. Summary of requirements Compliance justification Compliant? compliance Annual performance contract 1 Yes LG has submitted an annual • From MoFPED’s MoFPED records on submission of performance contract of the inventory/schedule of Annual Performance Contracts for FY forthcoming year by June 30 on the LG submissions of 2018/19 indicate that Nabilatuk DLG basis of the PFMAA and LG performance contracts, submitted on 29th July, 2019 which was Budget guidelines for the coming check dates of within the adjusted date of 31st August, financial year. submission and 2019 by OPM issuance of receipts and: o If LG submitted before or by due date, then state ‘compliant’ o If LG had not submitted or submitted later than the due date, state ‘non- compliant’ • From the Uganda budget website: www.budget.go.ug, check and compare recorded date therein with date of LG submission to confirm. Supporting Documents for the Budget required as per the PFMA are submitted and available 2 Yes LG has submitted a Budget that • From MoFPED’s Nabilatuk DLG submitted a Budget that includes a Procurement Plan for inventory of LG budget incorporated the LG Procurement Plan the forthcoming FY by 30th June submissions, check for the forthcoming FY (2019/2020) on (LG PPDA Regulations, 2006). whether: 29th July, 2019 and was received by MoFPED on 30st July, 2019. -

Uganda Work Plan FY 2018 Project Year 7

Uganda Work Plan FY 2018 Project Year 7 October 2017–September 2018 ENVISION is a global project led by RTI International in partnership with CBM International, The Carter Center, Fred Hollows Foundation, Helen Keller International, IMA World Health, Light for the World, Sightsavers, and World Vision. ENVISION is funded by the US Agency for International Development under cooperative agreement No. AID-OAA-A-11- 00048. The period of performance for ENVISION is September 30, 2011 through September 30, 2019. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the US Agency for International Development or the US Government. ENVISION Project Overview The US Agency for International Development (USAID)’s ENVISION project (2011–2019) is designed to support the vision of the World Health Organization (WHO) and its member states by targeting the control and elimination of seven neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), including lymphatic filariasis (LF), onchocerciasis (OV), schistosomiasis (SCH), three soil-transmitted helminths (STH; roundworm, whipworm, and hookworm), and trachoma. ENVISION’s goal is to strengthen NTD programming at global and country levels and support ministries of health (MOHs) to achieve their NTD control and elimination goals. At the global level, ENVISION—in close coordination and collaboration with WHO, USAID, and other stakeholders—contributes to several technical areas in support of global NTD control and elimination goals, including the following: • Drug and diagnostics procurement, -

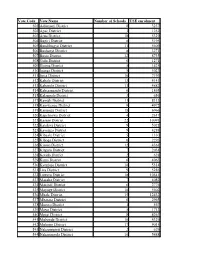

Vote Code Vote Name Number of Schools USE Enrolment 501

Vote Code Vote Name Number of Schools USE enrolment 501 Adjumani District 8 3237 502 Apac District 3 1252 503 Arua District 18 5329 504 Bugiri District 8 5195 505 Bundibugyo District 11 5609 506 Bushenyi District 8 3271 507 Busia District 12 8735 508 Gulu District 6 1271 509 Hoima District 5 1425 510 Iganga District 5 5023 511 Jinja District 10 7193 512 Kabale District 13 4143 513 Kabarole District 11 4882 514 Kaberamaido District 6 1865 515 Kalangala District 3 656 517 Kamuli District 11 8313 518 Kamwenge District 9 4972 519 Kanungu District 18 6966 520 Kapchorwa District 4 2617 521 Kasese District 22 10091 522 Katakwi District 9 5021 523 Kayunga District 9 4288 524 Kibaale District 5 1330 525 Kiboga District 6 2293 526 Kisoro District 12 4361 527 Kitgum District 7 2034 528 Kotido District 2 628 529 Kumi District 6 4063 530 Kyenjojo District 10 5314 531 Lira District 9 5286 532 Luwero District 18 10541 533 Masaka District 7 4082 534 Masindi District 6 2776 535 Mayuge District 10 5602 536 Mbale District 15 12432 537 Mbarara District 6 2965 538 Moroto District 1 567 539 Moyo District 5 1713 540 Mpigi District 8 4263 541 Mubende District 10 4329 542 Mukono District 17 9015 543 Nakapiripirit District 2 629 544 Nakasongola District 10 5488 545 Nebbi District 5 2257 546 Ntungamo District 18 8412 547 Pader District 8 2856 548 Pallisa District 8 6661 549 Rakai District 14 7586 550 Rukungiri District 21 11111 551 Sembabule District 8 4162 552 Sironko District 10 5552 553 Soroti District 5 3421 554 Tororo District 17 13341 555 Wakiso District 14 -

Nabitaluk District Local Government

` Nabilatuk District Nutrition coordination designing context specific nutrition interventions THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA structure, the 3 Sub Counties (Lorengedwat, in the districts and formulate customized action CALL TO ACTION Lolachat, Nabilatuk), and 1 Town plans. Council(Nabilatuk) trained in multi sectoral NUTRITION ISSUE ACTION RESPONSIBLE A Stakeholder Mapping and Capacity GOVERNANCE AREA PERSON NABITALUK DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT nutrition implementation for improved nutrition Assessment exercise was conducted to ADVOCACY BRIEF ON STRENGTHENING NUTRITION GOVERNANCE FOR MULTI-SECTORAL RESPONSE outcomes. examine institutional arrangements and capacity Coordination and Poor supervision and coordination Advocate to the DLGs to adopt CAO, DNCC, DNFP partnerships: of nutrition sensitive activities regular support supervision to the Supported the district to conduct quarterly to plan, budget and manage the multi-sector implemented at community level by LLGs into their day to day activity District Nutrition Coordination Committee nutrition programs in the district. district staff M&E schedule to foster adoption meetings, and, joint monitoring and support and build capacity of LLG staff Annual briefs (Technical and Advocacy) have supervision activities to LLGs aimed at to support better multi sectoral been developed from relevant studies conducted strengthening the accountability framework for nutrition interventions. to guide the strategic coordination, planning, Multisectoral nutrition actions implemented in budgeting, implementation and monitoring of the district. Systems Poor appreciation of nutrition by Conduct in service training on CAO, DNCC, DNFP both nutrition specific and nutrition sensitive capacity Building non traditional sectors (Community nutrition sensitive programming to A Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Annual Workplan interventions in the district, LLGs, and (functional, Based Services, Education, critical staff from key nontraditional (FY 2019/20) was developed by the DNCC communities.