Internal Balance of Power in Russia and the Survival of Lukashenko’S Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boris Nemtsov 27 February 2015 Moscow, Russia

Boris Nemtsov 27 February 2015 Moscow, Russia the fight against corruption, embezzlement and fraud, claiming that the whole system built by Putin was akin to a mafia. In 2009, he discovered that one of Putin’s allies, Mayor of Moscow City Yury Luzhkov, BORIS and his wife, Yelena Baturina, were engaged in fraudulent business practices. According to the results of his investigation, Baturina had become a billionaire with the help of her husband’s connections. Her real-estate devel- opment company, Inteco, had invested in the construction of dozens of housing complexes in Moscow. Other investors were keen to part- ner with Baturina because she was able to use NEMTSOV her networks to secure permission from the Moscow government to build apartment build- ings, which were the most problematic and It was nearing midnight on 27 February 2015, and the expensive construction projects for developers. stars atop the Kremlin towers shone with their charac- Nemtsov’s report revealed the success of teristic bright-red light. Boris Nemtsov and his partner, Baturina’s business empire to be related to the Anna Duritskaya, were walking along Bolshoy Moskovo- tax benefits she received directly from Moscow retsky Bridge. It was a cold night, and the view from the City government and from lucrative govern- bridge would have been breathtaking. ment tenders won by Inteco. A snowplough passed slowly by the couple, obscuring the scene and probably muffling the sound of the gunshots fired from a side stairway to the bridge. The 55-year-old Nemtsov, a well-known Russian politician, anti-corrup- tion activist and a fierce critic of Vladimir Putin, fell to the ground with four bullets in his back. -

Organized Crime 1.1 Gaizer’S Criminal Group

INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER I. ORGANIZED CRIME 1.1 Gaizer’s Criminal Group ..................................................................................6 1.2 Bandits in St. Petersburg ............................................................................ 10 1.3 The Tsapok Gang .......................................................................................... 14 Chapter II.CThe Corrupt Officials 2.1 «I Fell in Love with a Criminal» ................................................................20 2.2 Female Thief with a Birkin Bag ...............................................................24 2.3 «Moscow Crime Boss».................................................................................29 CONTENTS CHAPTER III. THE BRibE-TAKERS 3.1 Governor Khoroshavin’s medal «THE CRIMINAL RUSSIA PARTY», AN INDEPENDENT EXPERT REPORT «For Merit to the Fatherland» ..................................................................32 PUBLISHED IN MOSCOW, AUGUST 2016 3.2 The Astrakhan Brigade ...............................................................................36 AUTHOR: ILYA YASHIN 3.3 A Character from the 1990s ......................................................................39 MATERiaL COMPILING: VERONIKA SHULGINA HAPTER HE ROOKS TRANSLATION: C 4. T C EVGENia KARA-MURZA 4.1 Governor Nicknamed Hans .......................................................................42 GRAPHICS: PavEL YELIZAROV 4.2 The Party -

The Long Arm of Vladimir Putin: How the Kremlin Uses Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties to Target Its Opposition Abroad

The Long Arm of Vladimir Putin: How the Kremlin Uses Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties to Target its Opposition Abroad Russia Studies Centre Policy Paper No. 5 (2015) Dr Andrew Foxall The Henry Jackson Society June 2015 THE LONG ARM OF VLADIMIR PUTIN Summary Over the past 15 years, there has been – and continues to be – significant interchange between Western and Russian law-enforcement agencies, even in cases where Russia’s requests for legal assistance have been politicaLLy motivated. Though it is the Kremlin’s warfare that garners the West’s attention, its ‘lawfare’ poses just as significant a threat because it undermines the rule of law. One of the chief weapons in Russia’s ‘lawfare’ is the so-called ‘Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty’ (MLAT), a bilateral agreement that defines how countries co-operate on legal matters. TypicaLLy, the Kremlin will fabricate a criminaL case against an individual, and then request, through the MLAT system, the co-operation of Western countries in its attempts to persecute said person. Though Putin’s regime has been mounting, since 2012, an escalating campaign against opposition figures, the Kremlin’s use of ‘lawfare’ is nothing new. Long before then, Russia requested – and received – legal assistance from Western countries on a number of occasions, in its efforts to extradite opposition figures back to Russia. Western countries have complied with Russia’s requests for legal assistance in some of the most brazen and high-profile politicaLLy motivated cases in recent history, incLuding: individuals linked with Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the Yukos affair; Bill Browder and others connecteD to Hermitage Capital Management; and AnDrey Borodin and Bank of Moscow. -

Dissertation Final Aug 31 Formatted

Identity Gerrymandering: How the Armenian State Constructs and Controls “Its” Diaspora by Kristin Talinn Rebecca Cavoukian A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Kristin Cavoukian 2016 Identity Gerrymandering: How the Armenian State Constructs and Controls “Its” Diaspora Kristin Talinn Rebecca Cavoukian Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation examines the Republic of Armenia (RA) and its elites’ attempts to reframe state-diaspora relations in ways that served state interests. After 17 years of relatively rocky relations, in 2008, a new Ministry of Diaspora was created that offered little in the way of policy output. Instead, it engaged in “identity gerrymandering,” broadening the category of diaspora from its accepted reference to post-1915 genocide refugees and their descendants, to include Armenians living throughout the post-Soviet region who had never identified as such. This diluted the pool of critical, oppositional diasporans with culturally closer and more compliant emigrants. The new ministry also favoured geographically based, hierarchical diaspora organizations, and “quiet” strategies of dissent. Since these were ultimately attempts to define membership in the nation, and informal, affective ties to the state, the Ministry of Diaspora acted as a “discursive power ministry,” with boundary-defining and maintenance functions reminiscent of the physical border policing functions of traditional power ministries. These efforts were directed at three different “diasporas:” the Armenians of Russia, whom RA elites wished to mold into the new “model” diaspora, the Armenians of Georgia, whose indigeneity claims they sought to discourage, and the “established” western diaspora, whose contentious public ii critique they sought to disarm. -

'Belarus – a Significant Chess Piece on the Chessboard of Regional Security

Journal on Baltic Security , 2018; 4(1): 39–54 Editorial Open Access Piotr Piss* ‘Belarus – a significant chess piece on the chessboard of regional security DOI 10.2478/jobs-2018-0004 received February 5, 2018; accepted February 20, 2018. Abstract: Belarus is often considered as ‘the last authoritarian state in Europe’ or the ‘last Soviet Republic’. Belarusian policies are not a popular research topic. Over the past years, the country has made headlines mostly as a regime violating human rights. Since the Russian aggression on Ukraine, Belarus has been getting renewed attention. Minsk was the scene of a series of talks that aim at stopping the ongoing war in Ukraine. Western media, scholars and society got a reminder that Eastern Europe was not a conflict-free zone. This article puts military security policy of Belarus into perspective by showing that Belarus ‘per se’ is not a threat for neighboring countries; Belarus dependency towards Russia is huge; thus, Minsk has a small capability to run its own independent security policy; military potential of Belarus is significant in the region, but gap in equipment and training between NATO and Belarus is really more; it is in the interest of Western countries to keep the Lukashenko’s regime in Belarus. Keywords: Belarus; conflict; defence; security; NATO; Russia. Belarus is often considered as ‘the last authoritarian state in Europe’ or the ‘last Soviet Republic’. Belarusian policies are not a popular research topic. Over the past years, the country has made headlines mostly as a regime violating human rights. Since the Russian aggression on Ukraine, Belarus has been getting renewed attention. -

An Integrated Irish Aviation Policy

An Integrated Irish Aviation Policy Submission to the Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport Consultation Chambers Ireland|Air Transport User’s Council|Submission to the Irish Aviation Authority|June 2013 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 2 Airports ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Access to Infrastructure ......................................................................................................... 3 Future Airport Capacity Needs .............................................................................................. 3 Regional Airports ................................................................................................................... 4 Pricing of Air services ................................................................................................................. 5 Irish Airlines............................................................................................................................ 5 Connectivity ........................................................................................................................... 6 Air Travel Tax.......................................................................................................................... 7 Cargo Services ........................................................................................................................... -

Energy Politics of Ukraine: Domestic and International Dimensions

ENERGY POLITICS OF UKRAINE: DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ANASTASIYA STELMAKH IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS MAY 2016 i ii Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha B. Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Özlem Tür Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Meliha B. Altunışık (METU, IR) Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever (METU, IR) Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU, IR) Prof. Dr. Fırat Purtaş (GAZI U., IR) Assist. Prof. Dr. Yuliya Biletska (KARABÜK U., IR) iii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Anastasiya Stelmakh Signature : iii ABSTRACT ENERGY POLITICS OF UKRAINE: DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS Stelmakh, Anastasiya Ph.D., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever May 2016, 349 pages This PhD thesis aims to analyze domestic and international dimensions of Ukraine’s energy politics. -

Motivational Factors That Drive Russian Women Towards Entrepreneurship

Master Thesis Motivational Factors That Drive Russian Women Towards Entrepreneurship Author: Iana Sibiriakova & Nikita Lutokhin Supervisor: Frederic Bill Examiner: Åsa Gustafsson Term: VT19 Subject: Degree Project in Business Administration Level: Master Course code: 4FE25E Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this master thesis is to offer a number of illustrations of Russian female entrepreneurs in order to identify potential motivational factors that make Russian women launch their own business start-ups. Design/methodology/approach – The qualitative research method is applied within the master thesis based on information received from secondary (case studies) and primary (semi-structured interviews) data collection methods. The actor view and combination of directed and summative approaches of the qualitative content analysis update the information gathered within the theoretical studies of peer-reviewed articles on female entrepreneurship in general and particularly in Russia. Findings – Female entrepreneurs are not a homogenous group. Motivational factors can be divided in two groups: both applicable to male and female entrepreneurship; exclusively female motivations. “The glass ceiling effect” is a common problem that pushes women into self-employment. “Internal-stable reasons” encourage women entrepreneurship as an opportunity to achieve work-life balance and be one’s own boss. The desire of social contribution is a driver of female entrepreneurship, too. Marriage and birth of children make females think about starting their own businesses as well. Female entrepreneurship discrimination in Russia still exists up to now, in particular: sexism and dalliance. The principle motivational factors for women entrepreneurs in Russia are: wholesome family relationship and family support. One can behold a developing positive trend inside the boundaries of various discrimination problems that used to frustrate the majority of females determined to embark on entrepreneurial activity. -

Belarus: Country Background Report

Order Code 95-776 F Updated September 28, 2001 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Belarus: Country Background Report -name redacted- Specialist in European Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary This short report provides information on Belarus’s history, political and economic situation, human rights record, foreign policy, and U.S. relations with Belarus. It will be updated when necessary. History Belarus at a Glance Belarusians are descendants of Slavic tribes that migrated into the Land Area: 80,154 sq. mi., slightly smaller region in the ninth century. The than Kansas. beginnings of their development as a distinct people can be traced from the 13th century, when the Mongols Population: 10 million (2000 estimate) conquered Russia and parts of Ukraine, while Belarusians became Ethnic Composition: 77.9% Belarusian, part of (and played a key role in) the 13.2% Russian, 4.1% Polish and 2.9% Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1569, Ukrainian. the Grand Duchy merged with Poland, ushering in over two Gross Domestic Product (GDP): $12.67 centuries of Polish rule. Poland itself billion in 1999 (EIU estimate at market was divided in the late 18th century, exchange rate). and Belarusian territories fell to Russia. Political Leaders: President: Aleksandr Lukashenko; Prime Minister: Vladimir Ruling powers (i.e. Poles and Yermoshin; Foreign Minister: Mikhail Kvotsov; Russians) tried to culturally Defense Minister: Leonid Maltsev assimilate Belarusians and pushed Sources: World Bank, International Monetary them to the lowest rungs of the Fund, Economist Intelligence Unit. socio-economic ladder. As a result, Belarus did not develop a substantial national movement until the late 19th century. -

Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies Website of the Expert Community of Belarus «Nashe Mnenie» (Our Opinion)

1 BELARUSIAN INSTITUTE FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES WEBSITE OF THE EXPERT COMMUNITY OF BELARUS «NASHE MNENIE» (OUR OPINION) BELARUSIAN YEARBOOK 2010 A survey and analysis of developments in the Republic of Belarus in 2010 Minsk, 2011 2 BELARUSIAN YEARBOOK 2010 Compiled and edited by: Anatoly Pankovsky, Valeria Kostyugova Prepress by Stefani Kalinowskaya English version translated by Mark Bence, Volha Hapeyeva, Andrey Kuznetsov, Vladimir Kuznetsov, Tatsiana Tulush English version edited by Max Nuijens Scientific reviewers and consultants: Miroslav Kollar, Institute for Public Affairs, Program Director of the Slovak annual Global Report; Vitaly Silitsky, Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies (BISS, Lithuania); Pavel Daneiko, Belarusian Economic Research and Outreach Center (BEROC); Andrey Vardomatsky, NOVAK laboratory; Pyotr Martsev, BISS Board member; Ales Ancipenka, Belaru- sian Collegium; Vladimir Dunaev, Agency of Policy Expertise; Viktor Chernov, independent expert. The yearbook is published with support of The German Marshall Fund of the United States The opinions expressed are those of the authors, and do not necessari- ly represent the opinion of the editorial board. © Belarusian Institute for Strategic ISSN 18224091 Studies 3 CONTENTS EDITORIAL FOREWORD 7 STATE AUTHORITY Pyotr Valuev Presidential Administration and Security Agencies: Before and after the presidential election 10 Inna Romashevskaya Five Hundred-Dollar Government 19 Alexandr Alessin, Andrey Volodkin Cooperation in Arms: Building up new upon old 27 Andrey Kazakevich -

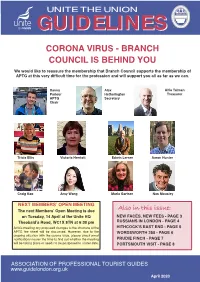

Branch Council Is Behind

CORONA VIRUS - BRANCH COUNCIL IS BEHIND YOU We would like to reassure the membership that Branch Council supports the membership of APTG at this very difficult time for the profession and will support you all as far as we can. Danny Alex Alfie Talman Parlour Hetherington Treasurer APTG Secretary Chair Tricia Ellis Victoria Herriott Edwin Lerner Aaron Hunter Craig Kao Amy Wang Maria Gartner Nan Mousley NEXT MEMBERS’ OPEN MEETING The next Members’ Open Meeting is due Also in this issue: on Tuesday, 14 April at the Unite HQ NEW FACES, NEW FEES - PAGE 3 Theobald’s Road, WC1X 8TN at 6:30 pm RUSSIANS IN LONDON - PAGE 4 At this meeting any proposed changes to the structure of the HITHCOCK’S EAST END - PAGE 5 APTG fee sheet will be discussed. However, due to the WORDSWORTH 250 - PAGE 6 ongoing situation with the corona virus, please check email notifications nearer the time to find out whether the meeting PRUDIE FINCH - PAGE 7 will be taking place or needs to be postponed to a later date. PORTSMOUTH VISIT - PAGE 8 ASSOCIATION OFASSOCIATION PROFESSIONAL OF PROFESSIONALTOURIST GUIDES TOURIST GUIDES www.guidelondon.org.ukwww.guidelondon.org.uk September 2019 April 2020 Union news THE CORONA VIRUS: FACTS AND FEARS Co-ordinated Action by Guiding Organisations What is being done for blue badge guides Advice on fighting the corona virus APTG, the Institute of Tourist Guiding, the Guild, and the Frequent and thorough hand-washing: twenty seconds with Driver Guides Association have all agreed to come together soap and hot water or sanitiser gel (if you can access it) is for the benefit of their members at this exceptional time to: recommended. -

OSW Report | Opposites Put Together. Belarus's Politics of Memory

OPPOSITES PUT TOGETHER BELARUS’S POLITICS OF MEMORY Kamil Kłysiński, Wojciech Konończuk WARSAW OCTOBER 2020 OPPOSITES PUT TOGETHER BELARUS’S POLITICS OF MEMORY Kamil Kłysiński, Wojciech Konończuk © Copyright by Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt EDITOR Szymon Sztyk CO-OPERATION Tomasz Strzelczyk, Katarzyna Kazimierska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH DTP IMAGINI PHOTOGRAPH ON COVER Jimmy Tudeschi / Shutterstock.com Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, 00-564 Warsaw, Poland tel.: (+48) 22 525 80 00, [email protected] www.osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-56-2 Contents MAIN POINTS | 5 INTRODUCTION | 11 I. THE BACKGROUND OF THE BELARUSIAN POLITICS OF MEMORY | 14 II. THE SEARCH FOR ITS OWN WAY. ATTEMPTS TO DEFINE HISTORICAL IDENTITY (1991–1994) | 18 III. THE PRO-RUSSIAN DRIFT. THE IDEOLOGISATION OF THE POLITICS OF MEMORY (1994–2014) | 22 IV. CREATING ELEMENTS OF DISTINCTNESS. A CAUTIOUS TURN IN MEMORY POLITICS (2014–) | 27 1. The cradle of statehood: the Principality of Polotsk | 28 2. The powerful heritage: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania | 32 3. Moderate scepticism: Belarus in the Russian Empire | 39 4. A conditional acceptance: the Belarusian People’s Republic | 47 5. The neo-Soviet narrative: Belarusian territories in the Second Polish Republic | 50 6. Respect with some reservations: Belarus in the Soviet Union | 55 V. CONCLUSION. THE POLICY OF BRINGING OPPOSITES TOGETHER | 66 MAIN POINTS • Immediately after 1991, the activity of nationalist circles in Belarus led to a change in the Soviet historical narrative, which used to be the only permit ted one. However, they did not manage to develop a coherent and effective politics of memory or to subsequently put this new message across to the public.